In Texas’ about-face, an example for Florida's dental program

Maggie Clark’s reporting on Florida’s Medicaid program for children was undertaken as a project for the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism, a program of the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Medicaid in Florida: 2 million kids. $24 billion battle.

Fighting for care in Florida's Medicaid system

An impossible choice: Doctors torn between patients and Florida's Medicaid system

2 Million Kids' series spurs support and quest for more data

Medicaid settlement: Florida will work harder to ensure health care for children

Dr. Howard Hunt, checks 2-year-old Ivan Reyes of Del Rio, Texas, for cavities as his mother Josefina Garcia holds her son down on July 11, 2016. Hunt uses a technique in which he lays the child's head in his lap while the mother holds on to his body while trying to calm the child down as dental assistant Miranda Palamof looks on. Photo by Jamie Bridges

DEL RIO, Texas — Less than 10 years ago, Texas’ Medicaid dental program looked a lot like Florida’s today. One in two kids never saw a dentist. And when they did, they had decay so severe that they often had to have their teeth pulled in the operating room.

But these days, hundreds of Texas pediatric dentists spend their days like Dr. Howard Hunt — counseling parents about the importance of taking care of their young children’s teeth.

Less than five miles from the U.S.-Mexico border, Hunt’s practice, Amigo Children’s Dental, performs hundreds of preventive visits each year. These frequent visits, virtually unheard of in Florida, are part of Texas’ “first dental home” program, a dental disease prevention program created by the Texas legislature to provide access to dental care for children starting at six months of age.

The goals: Stop the progression of dental disease in young children and save money by avoiding costly tooth extractions and dental surgeries in the future.

“Dollars spent on prevention can go a lot further in the long run,” said Hunt, who performs hundreds of first dental home visits for Medicaid-enrolled children each year.

“If we can educate the parents, watch the kids from an early age and develop relationships, we see great results and the kids develop life-long good oral health habits,” said Hunt, who also is the president of the Texas Academy of Pediatric Dentistry.

Maria Gonzalez tries to make her 11-month-old daughter Corazon Selbera, of Del Rio, Texas, smile as Dr. Howard Hunt examines her new teeth on July 11. Photo by Jamie Bridges

Texas’ Medicaid program hasn’t always been focused on prevention.

It took a U.S. Supreme Court ruling to change officials’ minds.

San Antonio dentist Dr. William Steinhauer vividly remembers the days before the state settled a 14-year lawsuit in 2007.

“There would be times where you would feel like, ‘My God, haven’t I fixed every kid in the city?’” Steinhauer said.

“But the cavities just kept on coming.”

The program had no infrastructure for prevention. And Steinhauer was one of the few dentists who even accepted Medicaid-enrolled children.

The rest balked at the program’s paltry reimbursement rates and complicated payment bureaucracy.

§

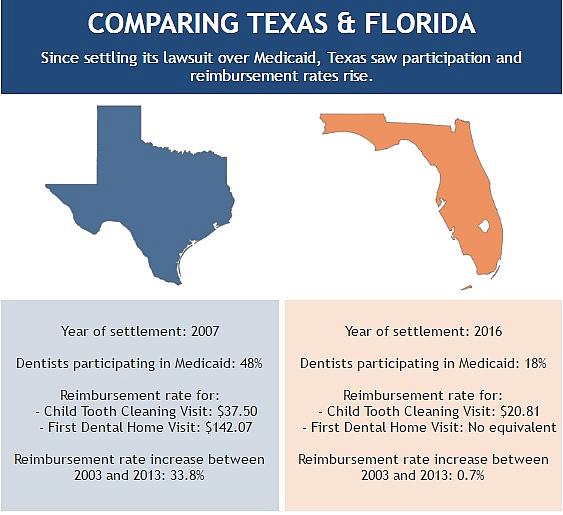

The situation in 2007 in Texas is strikingly similar to Florida today.

Florida pediatric dentists, doctors and parents settled a lawsuit against the state in April. The state agreed to change the Medicaid system to entice more providers — only about 18 percent of dentists accept Medicaid and many of those are not taking new patients — and increase the percentage of children getting preventive dental care and treatment. Currently, two out of three Florida kids enrolled in Medicaid get no dental services.

Faced with a complicated settlement agreement in 2007, Texas’ Medicaid agency, Legislature and medical and dental community joined to take action.

Under the watch of a federal judge, who could have taken over the state’s Medicaid program if they didn’t hold up their end of the agreement, Texas leaders created a system based in the latest medical science to promote preventive care for children and save the state money by avoiding expensive surgeries and hospitalizations.

Texas’ turnaround holds lessons for Florida, which continues to struggle with connecting kids with dental care and consistently ranks among the bottom of states in the percentages of children who ever see a dentist.

“We’re years behind Texas, but we’re hoping the settlement will give us some of the same results they achieved so that the children of Florida on Medicaid will finally receive the care they desperately need,” said Jolene Paramore, a dentist from Panama City, and second vice president of the Florida Dental Association.

The situation in 2007 in Texas is strikingly similar to Florida today.

Florida pediatric dentists, doctors and parents settled a lawsuit against the state in April. The state agreed to change the Medicaid system to entice more providers — only about 18 percent of dentists accept Medicaid and many of those are not taking new patients — and increase the percentage of children getting preventive dental care and treatment. Currently, two out of three Florida kids enrolled in Medicaid get no dental services.

Faced with a complicated settlement agreement in 2007, Texas’ Medicaid agency, Legislature and medical and dental community joined to take action.

Under the watch of a federal judge, who could have taken over the state’s Medicaid program if they didn’t hold up their end of the agreement, Texas leaders created a system based in the latest medical science to promote preventive care for children and save the state money by avoiding expensive surgeries and hospitalizations.

Texas’ turnaround holds lessons for Florida, which continues to struggle with connecting kids with dental care and consistently ranks among the bottom of states in the percentages of children who ever see a dentist.

“We’re years behind Texas, but we’re hoping the settlement will give us some of the same results they achieved so that the children of Florida on Medicaid will finally receive the care they desperately need,” said Jolene Paramore, a dentist from Panama City, and second vice president of the Florida Dental Association.

In Texas, about 48 percent of dentists accepted Medicaid in 2013, according to an analysis from the American Dental Association’s Health Policy Institute. In Florida for that same year, just 18 percent of dentists participated in the Medicaid program, according to the Florida Department of Health’s dentist workforce survey.

However, because dentists who are enrolled in Medicaid do not have to accept any new patients or see a minimum number of Medicaid patients in any given year, the percentage of dentists fully participating in Medicaid is likely lower, according to the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration.

Once Texas raised its reimbursement rates, the number of dentists willing to see Medicaid patients shot up, Hunt said.

The higher reimbursement rates “made it so that you could do good and also fill your schedule,” Hunt said.

This stands in sharp contrast to Florida, where most dentists refuse to participate in the Medicaid program and instead volunteer or offer free care on an irregular basis. Nearly two-thirds of Florida dentists said they’d volunteered to treat needy patients, although about 33 percent of those dentists said they’d only volunteered between one and eight hours over the course of two years, according to the Florida Department of Health workforce survey.

Florida Dental Association leaders say the current Medicaid program is so dysfunctional, charity is often the only, if unsatisfactory, choice for dentists who want to serve low-income patients.

“Charity is not the solution to this issue,” said Joe Anne Hart, director of government affairs at the Florida Dental Association. The dental association has for years advocated for meaningful initiatives to address the barriers that keep kids from getting care, but those pleas have fallen on deaf ears in the Legislature, Hart said.

She is hopeful that Florida’s Medicaid agency will follow Texas’ example following the settlement and seek input from dentists and pediatricians on ways to help connect more kids with care.

§

Data on the outcomes of Texas’ first dental home program is hard to come by.

Because the state transitioned from a fee-for-service system to a managed care system during the early years of the first dental home program, the data on a child’s health status is fragmented across several systems.

Currently, researchers at Texas A&M University are working on a multiyear study on the effectiveness of the program, but anecdotally, dentists say they’ve seen a huge difference in the children who’ve grown up having the preventive visits versus their older siblings who missed out on those visits.

“I’ve gone from a practice that was mostly surgical and restorative to a practice now that is 90 percent preventive,” Steinhauer said. “I can go weeks without seeing a cavity. That right there tells you the success of this program. The kids who are going through the first dental home program are not getting the diseases their older siblings experienced before the program started.”

Coretta Daniel, center, delivered her second baby, Zaria, with the help of BBC doula and founder, Christin Farmer. She says the group's services are "so needed" in her community, and can't wait to see them expand. (Thomas Ondrey, The Plain Dealer)

Texas is not the only state that made big changes after a lawsuit.

In Connecticut, following a Medicaid settlement there, lawmakers more than doubled reimbursement rates for regular dental services such as exams and cleanings.

The state saw the percentage of kids getting dental care skyrocket from 33 percent of children receiving dental services in 2006, before the lawsuit settled, to 60 percent of children receiving a visit in 2011, three years after the settlement, according to data submitted by Connecticut to the federal government.

While simply raising reimbursement rates is not a panacea for every problem in the Medicaid dental program, several studies have shown that states that raise their reimbursement rates see a significant increase in the number of children getting care.

Raising reimbursement rates, however, did come with some drawbacks for Connecticut.

After the rates went up, the state was inundated with corporate dental chains, including Kool Smiles, an Atlanta-based chain with offices nationwide. Almost right away, the state’s Medicaid agency noticed a big increase in claims submitted for medically-unnecessary fillings. The same thing happened in Texas when Kool Smiles and other dental chains set up shop in the state after the legislature raised reimbursement rates.

Additionally, Texas saw a spike in the number of braces ordered for children after it raised its reimbursement rates in 2007. An inspector general’s report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issued in June 2015 found that Texas paid approximately $191 million in reimbursements for unallowable orthodontic services, and owes the federal government $133 million for its portion of those bad payments. In Texas, the federal government provides about 60 percent of the state’s overall Medicaid budget.

While these states have struggled with corporate providers, Steinhauer argues that raising rates is still an important step to take to increase access to care.

“If you don’t raise the rates, you’re not able to get the good dentists,” Steinhauer said. “They’re not going to take Medicaid at a loss. Yes, the increased rates could attract some bad actors, but knowing that it might happen, a state could be more proactive in setting up a surveillance type of system to identify those bad actors quickly.”

Any improvement in Florida’s Medicaid program would be welcome, and would have ripple effects throughout the education system and the economy, Paramore said.

“People who have poor oral health become a burden on the system, they suffer poor health and they often can’t keep a job,” Paramore said.

“Making childhood dental disease go away would affect people for their lifetime. It’s hard for us to understand how that investment is not important.”

As Florida lawmakers work to comply with the state’s settlement agreement, they can look to Texas, a state geographically and demographically similar, for guidance, said Dr. John Holcomb, chairman of the Texas Medical Association’s committee on Medicaid, the children’s health insurance program and access to care.

“None of these changes would have happened without the court decision,” Holcomb said.

[This story was originally published by the Herald-Tribune.]

Photos by Jamie Bridges/Herald-Tribune.