Toxic air. Insufficient monitors. Why Memphis families fighting Byhalia pipeline have had enough

This story is part of a larger project led by Sarah Macaraeg, a 2019 Data Fellow who is investigating the disproportionate number of asthma diagnoses and severe symptoms among Memphis children.

Other stories include:

5 things to know: How polluted streams interact with the Memphis Sand aquifer

Near Byhalia pipeline planned connection point, Valero leaked 800 gallons of crude oil in 2020

Byhalia pipeline: Toxic refinery pollution, monitoring blind spot in southwest Memphis

More than 100,000 people in Shelby County are facing a pandemic without health insurance

To halt 'fast-track' Byhalia pipeline permit, Memphis groups file lawsuit in federal court

Kizzy Jones, a co-founder of Memphis Community Against the Pipeline (MCAP), hold signs outside the National Civil Rights Museum with her family during a rally...

BRANDON DAHLBERG / FOR COMMERCIALAPPEAL.COM

For Kimberly Pearson and other families from southwest Memphis, the movement gaining momentum against the Byhalia Connection is about much more than a pipeline — or any one of the major sources of air pollution encircling the area her family has long called home.

Central High School educator Kimberly Owens-Pearson in Memphis, Tenn., on Saturday, March 6, 2021. ARIEL COBBERT/THE COMMERCIAL APPEAL

The pair started their family in the neighborhood and later moved while pursuing undergraduate and advanced degrees. But to Westwood they always return, to homes where their siblings live, passed on by the hard work of their parents and the elders that came before them.

Over the years they've seen industry rise and community investment decline in the area. "It makes me so upset because it keeps happening," Pearson said.

Transportation accounts for a major share of all air pollution. Stationary sources, such as the oil refinery, airport, steel mill and power plants encircling the nearly all-Black neighborhoods of southwest Memphis are among the rest.

Of all emissions Shelby County facilities reported in 2017: Sites in southwest Memphis accounted for 94% of 6.6 million total tons of six "criteria" air pollutants in the most recent National Emissions Inventory, compiled by the Environmental Protection Agency every three years.

The Clean Air Act sets limits on carbon monoxide, lead, ground-level ozone, particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide for a reason: Exposure is harmful to humans and can trigger asthma and other respiratory issues and increase the risk of other illnesses, the Centers for Disease Control states.

But when it comes to another set of air pollutants called air toxics, the consequences are such that emissions are measured not in tons but pounds. The 187 hazardous air pollutants are "suspected to cause cancer or other serious health effects, such as reproductive effects or birth defects," according to the EPA.

The Valero Memphis refinery was the top stationary source of air toxics in the 2017 inventory, sitting atop the same 38109 southwest Memphis zip code where families downwind of the refinery's emissions are fighting the eminent domain claims of the Byhalia Connection pipeline. Valero, which describes itself as the largest and lowest cost independent oil refiner in the U.S. is a partner on the project with Plains All American Pipeline, L.P.

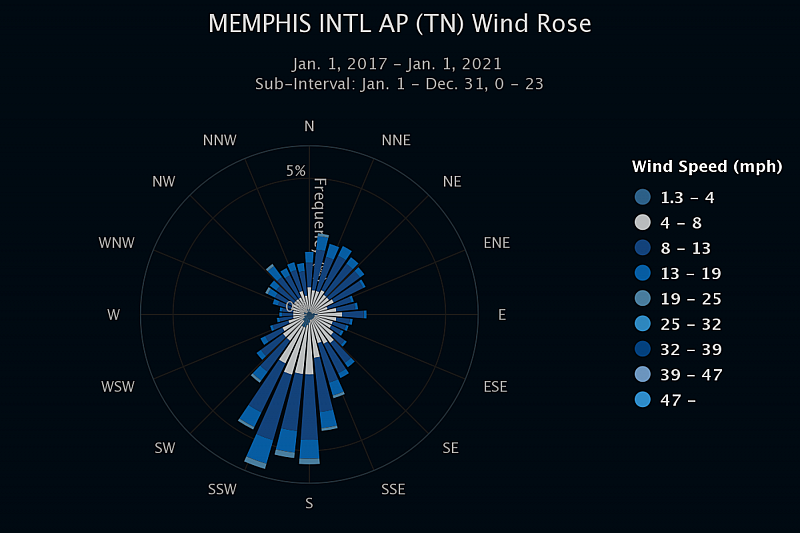

A wind rose, processed by the Midwestern Regional Climate Center, shows the speed and direction of winds recorded at the Memphis International Airport from Jan. 2017 to Jan. 2021.

More than 10,000 families make up the estimated population of nearly 45,000 people living in 38109, of whom 97% are Black and more than a one-fifth are children, according to the U.S. Census Bureau's 2019 American Community Survey.

Those working earned a median salary of around $26,000 — not enough to surpass the poverty threshold for more than a fifth of families. Thousands of seniors and people living with disabilities are among the population that's not employed.

More than half of families live in homes they own.

The Byhalia Connection's overtures includes $1 million in grant awards to community organizations ahead of local votes pivotal to the project — donation dollars that may be available due to taxpayers, according to BailoutWatch, a non-profit that tracks fossil fuel company benefits reaped through coronavirus economic stimulus measures.

Valero received a $238 million tax refund, and along with Plains, also benefited from bond and debt purchases by the Federal Reserve Bank, according to the watchdog group.

Refinery proximity increases cancer diagnosis risk

No matter how deep their pockets, corporations can't account for the reverence families have for their neighborhoods, said Kimberly Pearson.

"The home that my mother had passed down to her five children — she worked three to eleven on her feet," Kimberly Pearson said. "It's not just a house. My brother became ill and he's there now, he has somewhere he doesn't have to worry about, because that's our home," she said.

"For people to just act as if you're disposable, it hurts because we have history, we have memories, we have life," Kimberly Pearson said.

Among those memories are the all-nighters her mother pulled while studying to become a nurse as a single mom. She died of cancer at 68. Her husband, Pastor Jason Pearson's mother died of cancer at 63. Among new memories is their reunion during the COVID-19 pandemic with four sons in their twenties, all part of the movement to stop the Byhalia pipeline.

The EPA tracks the release of hazardous pollutants annually in the Toxic Release Inventory. The refinery's release of carcinogens, substances associated with cancer, rose 23% from 2017 to 2018 and then remained at nearly the same level in 2019, the data show.

The EPA cautions against drawing conclusions regarding facilities in its data, given the complexity of pollution sources in an environment.

But when it comes to oil refineries, a team of University of Texas public health researchers recently published a straightforward connection. "Proximity to an oil refinery was associated with an increased risk of multiple cancer types," their study of 6.3 million adults concluded after researchers compared diagnoses among people who lived within ten miles of a refinery with those 20-30 miles away.

Whether the planned pipeline might lead to a local ramp up in refinery operations, the San Antonio, Texas-based company didn't say in its succinct response Monday to multiple questions from The Commercial Appeal.

"It is Valero’s policy to not comment on operations," a spokesperson emailed.

Whether the company has sufficient insurance to cover a large-scale environmental clean-up or communicates or makes transparent to downwind communities any of its monitoring data or significant releases are among other questions on which Valero declined to comment.

Black Lives Matter: 'Keep that same energy' on clean air and water

The project is moving forward, if you ask Plains Vice President Roy Lamoreaux. In a letter addressed to Memphis residents released Saturday, he asserted the companies have the necessary federal, state and local permits in hand.

But the Byhalia pipeline isn't a done deal, with local votes and state legislation impending.

On one side of the fight is Valero's local clout; Plains' promise of jobs, grants and economic benefit; and assumptions regarding the safety and necessity of oil transport.

Squaring off against Big Oil are Black families fighting to protect their health, homes, loved ones and land, alongside Memphians long protective of the city's aquifer.

In raising the disproportionate pollution burden area residents already face, the movement families are leading against the pipeline is also an invitation and challenge, to any company, official or individual who has professed "Black Lives Matter".

As one of the Pearsons' sons, Keshaun, puts it, "Can you keep that same energy with protecting the aquifer...protecting the air that's being polluted and fighting against that?"

His brother, Justin J. Pearson, is a co-founder of Memphis Community Against the Pipeline, a months-old grassroots group that's sparked growing support, including from former Vice President Al Gore and activist/actors Danny Glover and Jane Fonda.

Justin J. Pearson, co-founder of Memphis Community Against the Pipeline

"We killed King here," Justin J. Pearson said of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination in Memphis. "But we don’t talk about the racism that's rooted here. If we continue to run from those conversations, we'll never do the reflective work that's necessary to say, 'How did we let a steel mill and all this industry go into the same communities?'"

He hopes elected officials with the power to intervene, from President Joe Biden to local officials, will ask themselves similar questions on what can be restored rather than extracted. "How did we let this happen, not how should we keep it going," Justin J. Pearson said.

"It is not imminent that we need to be extracting more oil, transporting more oil. Those things are not mandatory for our survival. What is mandatory for our survival is air, is water, is housing," he said.

Political power, public funds and pollution: A snapshot of Valero's time in Memphis

In Shelby County, Valero’s refinery operations have historically enjoyed a range of supports since the company purchased the site in 2005, including a 15-year, $25.8 million tax break package expiring in 2027; local backing on state legislation and a city ordinance the company sought to kill; and multi-million-dollar improvements to the highway interchange and Mississippi River harbor on which the company relies.

Chemical releases also mark Valero's time in Memphis: 1,500-gallons of diesel released into the harbor by a barge operator, 440 pounds of bleach into the ground, 528 pounds of hydrogen cyanide in the air and 500 pounds sulfur dioxide, released in an explosion, appear in state and federal regulatory agency records. The explosion was among a rash of incidents involving two separate worker deaths, between 2010-2012, Commercial Appeal archives show.

In a recent release of gases by burning known as a flare, a plume of fire over the refinery caught attention on social media in February. MLK50 reported on Valero's clean-up of Nonconnah Creek afterwards and the approximately 101 pounds of hydrogen sulfide and 501 pounds of sulfur dioxide released.

National Emissions Inventory data provides a yearlong example of "Emergency Flare" emissions, reported by the sum of each pollutant released in 2017: 7,810 pounds of volatile organic compounds, 1,825 pounds of sulfur dioxide, 3,785 pounds of Nitrogen Oxides and 17,255 pounds of carbon monoxide.

"The reality of living in this area, living in 38109, you are definitely exposed to the burning...at Valero," said Pastor Pearson. "All of that pollution gets into the air, then breathed into the lungs of the people."

He doesn't think it's a coincidence that two of his brothers who've consistently lived in the area have asthma. "They were even closer to the plant, over there by Nonconnah. Those two of my brothers have chronic, literally chronic asthma," Pastor Pearson said.

March 6, 2012 - A pair of ambulances pull out of the Valero oil refinery on Mallory following an explosion at the plant that... THE COMMERCIAL APPEAL FILE PHOTO

Valero is now among employers recognized by the Occupational Health and Safety Administration for maintaining below-average injury and illness rates. On March 2, a workplace safety complaint was lodged against Valero involving the Memphis refinery, OSHA data shows. The oversight agency does not disclose details on open investigations.

Valero is also under a federal consent decree agreement as of a $2.9 million settlement with the EPA in December, for non-compliance with gas and diesel fuel sampling at some sites, including Memphis, and non-compliance with emissions reductions standards regarding its fuel products at other sites, including a terminal across the Mississippi River in West Memphis, Arkansas.

A spokesperson for Biden's administration didn't say whether U.S. Rep. Steve Cohen's request that the President consider revoking the Byhalia pipeline's federal permit is under consideration.

The administration's policy involves approval on a case-by-case basis, the spokesperson said, based on energy needs, the creation of union jobs and Biden's goal to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. The spokesperson did not clarify whether those determinations include pipelines with existing federal approval.

On Valero's site, the company cites its industry awards; a ranking by Forbes among best multinational corporate employers; and in Memphis, monthly safety drills and $4.3 million donated to local charities.

Ahead of local votes on the project, Kimberly Pearson reflected on those who may be loyal to big business. "You can't drink money. You can't inhale money. You need to get your priorities straight."

Doubling oil capacity with 'no assurances' on clean-up

In a February investor filing, Valero states the company's insurance "may not be sufficient to cover all potential losses arising from operating hazards", attributing the gap to unreasonable rates.

Valero also warned investors the insurance it does have may not necessarily deliver.

"We can make no assurances that we will be able to obtain the full amount of our insurance coverage for insured events," the Valero document states.

As an extension of the Diamond Pipeline, which Plains and Valero operate between Cushing, Oklahoma, and the Memphis refinery, the Byhalia Connection would increase capacity from 200,000 barrels to 420,000 barrels per day, according to a Plains document received by the Securities and Exchange commission March 1. It includes similar language as Valero's filing regarding lacking insurance.

"Assets we have acquired or will acquire in the future may have environmental remediation liabilities for which we are not indemnified... insurance does not cover every potential risk that might occur, associated with operating pipelines, terminals and other facilities and equipment," the document states.

For a spill of more than 2,900 barrels of crude oil in 2015 on the California coast, remediation costs are at around $460 million, the Plains filing also states.

Plains did not provide comment on assurances potential remediation costs could be fully covered. The company has previously been proactive in addressing residents' contamination concerns, citing 10,000 hours spent in studying the Byhalia route's conditions, approximately four feet below ground.

The Memphis Sand aquifer is hundreds of feet beneath the surface, under a barrier of clay which protects the purified drinking water source, akin to a great lake. But, as scientists found before the proposed Byhalia pipeline entered the picture, the aquifer isn't impervious to contamination with at least 16 breaches in the clay.

"As part of our Diamond joint venture, we have safely owned and operated pipelines in and around Memphis without incident," the statement says in reference to the existing pipeline Plains has operated in Memphis since 2017.

"While incidents can happen, we strive to prevent them with careful design, continuous monitoring and ongoing maintenance. We also regularly train our people to be ready to respond just in case," Plains statement said, citing a monitoring and shut-off system, first responder training and the hiring of a "Memphis oil spill response organization" to be on call around the clock.

Air pollution is never equitable and poor communities can't escape it

Running atop the city's pristine drinking water supply, the course of the 49-mile Byhalia pipeline would pump crude oil from the Valero refinery to a terminal just over the Tennessee border in Mississippi. Valero leaked 800 gallons of crude oil near the site in January 2020.

Spills aren't the only environmental concern when it comes to the transport of oil that ultimately results in emissions, said Juan Declet-Barreto, a senior social scientist for climate vulnerability with the Union of Concerned Scientists.

He previously worked in the Air Quality Division of the Arizona Dept. of Environmental Quality where his work included compiling emissions inventories.

He said there's a reason water rights tend to draw more attention than demands for clean air. "We use it for one thing, to breathe. It's necessary, just like water is necessary. We cannot function, we cannot exist, we cannot live healthy lives or lives, period, without either of those," Declet-Barreto said.

"But water can also be used for many other things," he continued, "To generate power, to water crops, to grow food. The use of water is tied to large enterprise."

And where people across a jurisdiction draw drinking water from a common source through similar pipes, they experience similar water quality.

"With air, it doesn't work that way necessarily," Declet-Barreto said. "Proximity to sources, wind direction with relationship to the sources, are going to impact where the air pollutants go," he said. "The distribution of that throughout a city is not equal."

Even if pollution were equitably distributed, its impact never is, he said. Some people can use air conditioning at home and in their cars and have ample indoor space for everyone at home, thereby limiting their exposure.

"Low-income communities of color don’t have those luxuries," he said. And not everybody’s lungs or bodies have the same capacity to fight the effects, he said.

Growing up with asthma

When Tim Pearson thinks about growing up in Westwood, his favorite childhood memory is similar to his father's: Playing football in a street filled with family and friends.

But how he had to go about it was a lot different than his dad or his brothers, with an asthma diagnosis that first surfaced when he was hospitalized as a baby.

"I would have to sit out, every 15 or 20 minutes in order that I could breathe," Tim Pearson said. "All my brothers, they could play and, you know, run outside all day. But I had to come in and drink water, to sit down, to count to 10," he recalled. "It was strenuous just in order for me to play."

The Memphis Valero Refinery sits at the edges of Dr. Martin Luther King Riverside Park and the Mississippi River SARAH MACARAEG/COMMERCIAL APPEAL

As he became older he used an oxygen tank and the difficulty breathing wasn't always easy for him to absorb as a kid. Then, he said, "I realized it wasn't my fault."

Tim kept playing football, including at Mitchell High school, a site just south of the refinery, near the pipeline's route. He made All State in his Memphis career.

But it's the years before that, when the family relocated to Fairfax, Virginia, that stick with him.

"When we moved to Virginia, I wasn't having any of the regular problems that I was having, even with playing high intensity sports. When I moved back, I actually had to go back to the doctor in order to get an Albuterol, asthma pump. And I know it's due to the air," he said.

A comparison of Air Quality Index scores on days rated less than "Good" in 2015, the year the Pearson family moved back to Memphis, shows Shelby County and Fairfax County both had four days in the year that were officially "Unhealthy for sensitive groups", which includes children, seniors and people with pre-existing conditions.

But Shelby County had 19 more days than Fairfax at the "Moderate" level — considered acceptable for the general population but of potential risk to sensitive people.

That may not be the full story of a potential difference, though, given weaknesses in the EPA's air monitoring network, according to experts.

EPA measures risk

The Air Quality Index paints a daily picture based on readings of two common pollutants, particulate matter and ground-level ozone in an EPA network of monitors. Called AQI for short, the daily readings are available in phone apps and are meant to help people make choices about their exposure.

But a Reuters investigation found monitors in the network are prone to missing criteria air pollutants emitted by major sources and incidents — including refinery explosions.

To understand risk related to particularly hazardous air pollutants, the EPA maintains a different scoring system, the Risk-Screening Environmental Indicator model, to account for myriad variables, from air dispersal and specific chemical processes to transport or treatment of pollutants before their release.

The scores it churns out tally risk without limit for the purpose of comparison. The higher the number the greater the risk.

In the most recent RSEI score based on 2019 data, the Valero refinery's risk score was just shy of 58,000, more than seven times the median in the petroleum refining industry.

The refinery score is more than 1,600 times the median score of 36 in Shelby County, which has a majority-Black population compared to a population that's 17% Black in the state.

The median county risk is 1.7 times greater than a score of 21 at the state level, which is in turn higher than the median score across the U.S., of 14.

Breathing polluted air, 'bullied' by eminent domain claim

For Scottie Fitzgerald, the data dovetails with suspicions she's had since nursing school.

“About a whole neighborhood of people ended up with breast cancer, including my mother," she said, ticking through names of women she says lived in walking distance of one another.

She grew up near the site, the only child of blue collar workers together 50 years, who managed to purchase properties and buy a refrigerator for a neighbor in need. Over the years that the refinery's ownership has changed hands, its impact on the senses have remained in her mind.

The smell of rotten eggs is what Fitzgerald remembers about it from her childhood.

At the park where she and her husband used to go on dates, it's the sight of the refinery's smokestacks and the sound of its incessant production that fills the greenspaces of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Riverside Park.

At the fence line now are multiple devices, monitoring fugitive releases of the carcinogen benzene.

Fitzgerald left her longtime job at the Veterans Administration while her mother was sick. They had always been best friends, Fitzgerald said, and she cared for her mother for four years in hospice at her home.

"My mother was a very spiritual woman and she was a fighter," said Fitzgerald.

Elmeter Washington left her daughter, Scottie Fitzgerald, two parcels of land in Boxtown where the Byhalia Connection followed Fitzgerald's rejection of their offer for easements... SARAH MACARAEG/COMMERCIAL APPEAL

"She was still paying property taxes out of her little social security check, staying with me,” Fitzgerald recalled.

The payments were on two parcels of land she left to Fitzgerald, in the Boxtown neighborhood further south where reporting by MLK50 brought residents' resistance to light.

Seeking a permanent easement to build the pipeline, Byhalia filed an eminent domain claim against Fitzgerald. Along with multiple other families, she's fighting back in court with the help of a pro-bono lawyer, the Southern Environmental Law Center and Memphis Community Against the Pipeline.

"If I decide you got something in your backyard I want and just get with a conglomerate of people and say, 'We're gonna go over here and we don't care what you say,'" Fitzgerald said, "That's called bullying."

Plains said it's worked with other landowners to secure agreements for 95% of the route in which residents retain ownership of their land while the pipeline is constructed and occasional maintenance is performed. The company also noted 62 of the 67 of the parcels sought are vacant.

Just because she hasn't had a chance to build on the land, it doesn't mean the land doesn't hold future plans and a legacy to be passed on another generation, to her own daughter, Fitzgerald said.

"You don't just walk in and decide you gonna take something 'cause you got all the money....If they're allowed to do this to one person, that's what they can do to anybody," she said.

Since some of the properties are owned by Shelby County, a vote by county commissioners will play a role as the battle continues.

"We will be paying property taxes for seven miles of line, which will equate to millions in taxes over the decades the line will be in service," Plains said in a statement that also signaled its plans will move forward either way.

"We have also begun to evaluate other routes if we cannot purchase these properties. These alternative routes will cross other properties owned by Shelby County residents or businesses," Plains said.

For the parcels of land on which Valero operates the Memphis refinery, the company pays $100 per parcel per year, Shelby County trustee reports show. For its personal property on the site, Valero pays a quarter of taxes assessed under a payment-in-lieu-of-taxes agreement the Economic Development Growth Engine board granted to help Valero fund $289 million the company said it would spend on upgrades needed to expand and upgrade the facility and to conform with environmental regulations.

'We're already exposed'

Despite a concentration of source point polluters in southwest Memphis, ambient air quality monitors are located in East Memphis, Downtown, on the north side of the city, in Frayser and in the northern suburban municipality of Millington. The dominant wind pattern points south, climate data shows.

Corbett Grainger, a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor of environmental economics, said he wasn't surprised to see a hole in the monitoring network in Memphis.

Grainger led a study on the placement of monitors, using data from satellites with instruments able to estimate certain pollutants from space, a method called remote sensing.

The study compared pollution in locations with and without monitors. "We found monitors in some cities tend to miss highly-polluted areas," Grainger wrote in an email.

Two of Shelby County's monitor sites, in Frayser and Millington, date to 1990. The East Memphis monitor was sited in 2011 and a Downtown monitor was placed in 2016, according to EPA data. Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation spokesperson Kim Schofinksi said state and local monitoring plans are approved by the EPA annually, preceded by a public review period.

Dr. Chunrong Jia researches environmental health at the University of Memphis. He identified an air pollution "hot spot" in southwest Memphis in a study published in 2013 and said the lack of data makes it difficult "to fully address" the environmental justice issues in the area.

Whitehaven resident Kimberly Dobbins with her daughter Zaiyah Veasley COURTESY KIMBERLY DOBBINS / FOR COMMERCIALAPPEAL.COM

A mother of three kids, ages six to 13, Kimberly Dobbins lives in Whitehaven. She met their father while studying education at the University of Memphis. As the couple began navigating their kids' options, they decided to homeschool them, with Dobbins working at home as their teacher while her husband works in construction. "It was the private school we could afford," she said.

Dobbins took the trio to a recent rally against the pipeline as a "learning journey." For her, it was also a means to push on the disparities that have long troubled her.

“You just want your children operating and being healthy, mind, body and spirit. But then you have to fight these kinds of battles,” she said. "Because it's always like, ‘What's the future gonna be like for my kids?’”

Dobbins said she didn't have to think about participating in the movement to stop the pipeline.

"We're already exposed," she said. "When it comes to our neighborhoods, no one really cares about the fact that these corporations are in our neighborhoods with the amount of pollution that they're causing," said Dobbins.

"Those who own the corporations, who collaborate with the corporations, who have any affiliation with the corporations — they're not living in our neighborhoods. They don’t want their children exposed," she said.

MCAP founder says the Byhalia Pipeline connection would bring many risks to Memphians(2:46)

Justin J. Pearson, the co-founder of the grassroots group opposing the pipeline, is intent on disrupting the desensitization surrounding pollution.

'We have unfortunately allowed pollution to just become a word and to not realize its impact on very real people," he said.

"We can't keep operating like this as a city. And we're at a moment in time where we can really forge a new moment and a new movement in Memphis that creates something different than what we have been accustomed to over the last centuries," he said.

Shelby County Mayor Lee Harris wrote in an emailed statement that the placement of the county's ambient air monitors will be analyzed with experts.

"We likely need the monitors in more communities, particularly neighborhoods that have historically borne the brunt of environmental degradation," said Harris, who has voiced his opposition to the Byhalia Connection pipeline and the drilling plan of TVA that would have endangered the aquifer.

In Sept., the EPA awarded the Shelby County Health Dept. Air Pollution Control division a nearly $354,000 grant for community-scale monitoring. Dept. spokesperson Joan Carr described it as a pass-through grant to the University of Memphis "to get a broad database of samples from all parts of Shelby County and analyze them for the presence of unregulated pollutants." Currently, Carr said the Dept. is working to get the funding through the county budget process.

Jia, who previously identified a hot spot in southwest Memphis, will lead the effort. He's researching a specific set of pollutants, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which occur naturally in coal, crude oil and gasoline. Jia said it'll take another four to six months to determine if southwest Memphis residents are experiencing higher exposure to the pollutants, called PAHs.

In the meanwhile, during the budget season, Harris said he plans "to continue to fight tooth and nail to expand the county's investment in public transit, which can have an ameliorative effect on air pollution."

Harris said the county is "working hard to ensure that the costs of climate change, environmental degradation, and overreliance on fossil fuels don’t fall disproportionately on our historic communities."

In working with communities through the Union of Concerned Scientists, Declet-Barreto said addressing the "cumulative effects" of pollution on low-income communities of color would entail the commitment of multiple agencies.

Not only are different air pollutants regulated in different ways, he said. The means to address the circumstances that lead to communities being entrapped and encircled with pollution are disjointed, said Declet-Barreto.

"Access to affordable housing is some other agency’s problem. Transportation is some other agency’s problem. But communities experience all these things simultaneously without regard to geography, without regard to regulatory frameworks. They’re constantly targeted," he said.

No more 'sacrifice' zones

Tim Pearson, who grew up with asthma, has a lot of ideas on how environmental health initiatives could operate, based on his own experiences with asthma.

"Take on the responsibility of finding out how chronic asthma plays a part in the people that's around here lives'. Take a poll. How many kids, how many adults actually have asthma? [Is it] due to the environment, the chemicals that's being put in the air," Tim Pearson said.

"They have to be able to do something in order to stop it," he said. "Because it's an actual problem and people die."

Leaving shouldn't be a requirement for survival and 'sacrifice zones' aren't a concept anyone should accept, said two of the Pearson's sons. The term coined by founding member of the EPA's Office of Environmental Justice Mustafa Santiago Ali emblemizes sites across the country where, he told Mother Jones, "We place everything that nobody else wants."

Keshaun Pearson wants people to put themselves in their family's shoes.

"Wherever your family is from, you don't want them have to leave there to survive," he said. "They should be able to raise their kids, to come back to the community and continue to build up the community.

"If you have to escape to higher ground, then it becomes about resources... about who can afford to survive. You're buying back years of your life. And that's not a fight anybody should have to fight," he said, pausing as his brother jumped in.

"When you have people in government who is supposed to protect you, who had the resources to stop it, to not let it happen," said Jaylen Pearson.

The family's patriarch, Pastor Jason Pearson, said now is the time for leaders to be decisive.

"This is the watershed moment. Are you going to stand with poor and low-wealth people and help them to have clean air, help them to keep oil out of their soil? Or are you going to stand with someone who's going to give the city [money]," he said.

"Are we that desperate for financial prosperity that we're willing to risk the health of our people?"

Sarah Macaraeg's reporting on air pollution was undertaken as a USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism Data Fellow.

Macaraeg is an award-winning journalist who writes in-depth stories on accountability, solutions and communities for The Commercial Appeal. She can be reached at sarah.macaraeg@commercialappeal.com or on Twitter @seramak.

[This story was originally published by Commercial Appeal and USA Today.]