Tribune investigation: Inspections protect renters from slumlords. Why did SLO’s program die?

This story is part of a larger project, "Standard of Living," by Lindsey Holden, a participant in the 2019 Data Fellowship. The project focuses on the experiences of low-income renters living in poorly maintained housing in San Luis Obispo County.

Other stories in this series include:

Q&A on renter’s rights: What you need to know as a tenant in SLO County

Tribune investigation: What it’s like for SLO County renters stuck in bad housing

We surveyed nearly 200 SLO County renters on their housing conditions. Here’s what they said

Paso Robles couple says landlord covered up unhealthy mold problem. So they sued

Tribune investigation: Erratic code enforcement leaves SLO County renters vulnerable to abuse

The Tribune

Editor’s note: This is the third story in The Tribune’s “Substandard of Living” series examining the experiences of low-income renters living in poorly maintained housing in San Luis Obispo County. The Tribune spent nine months investigating the issue by talking to residents, conducting surveys, speaking to experts and evaluating government resources.

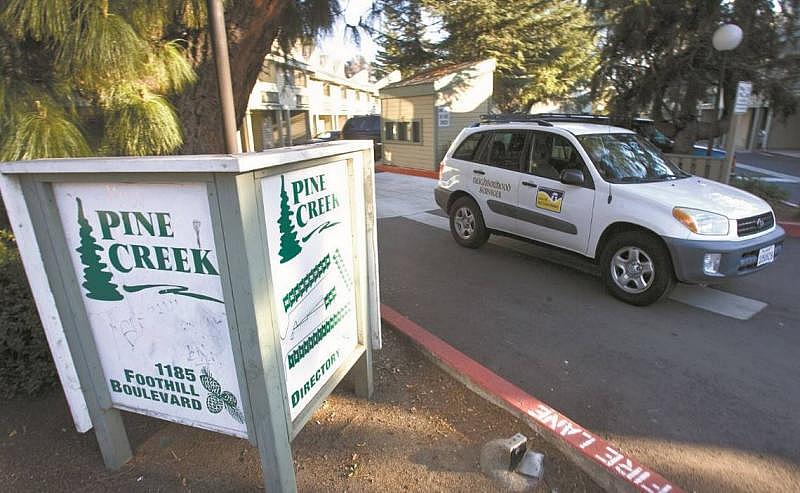

Seven years ago, dozens of San Luis Obispo college students went to sleep every night in makeshift bedrooms that were nothing less than fire traps.

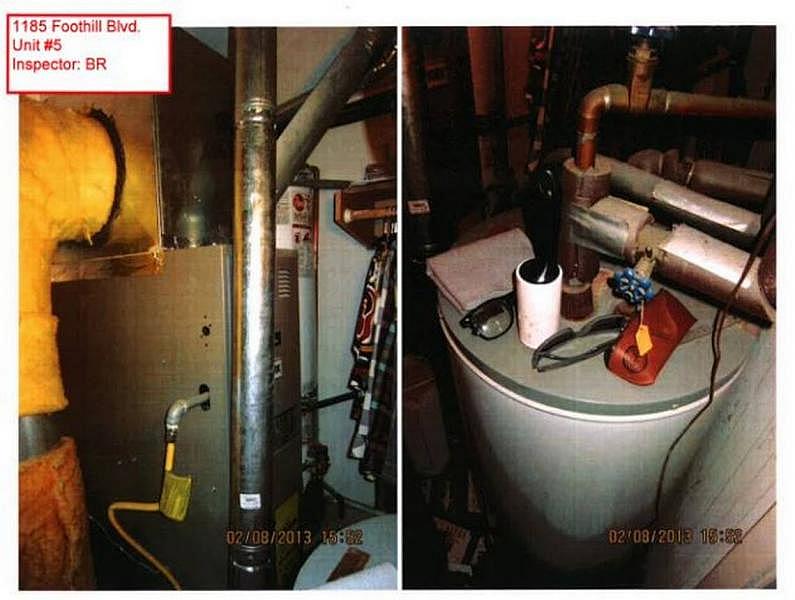

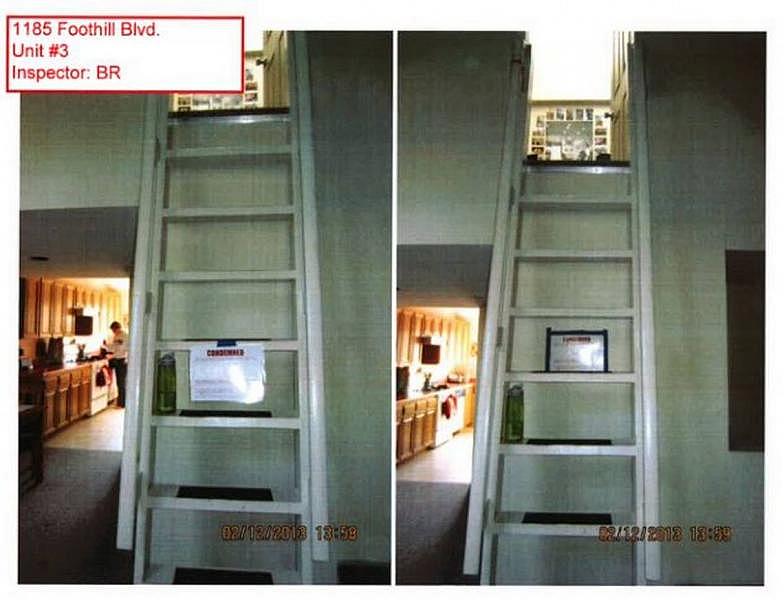

Their living conditions — in illegally converted loft bedrooms at the Pine Creek condominiums — required access by ladders and provided storage so close to hot water heaters and furnaces that their clothes would heat up.

The only way out of most of these 34 loft rooms, which were originally built as storage spaces, was by climbing down rungs or going out windows too small for firefighters to access in the event of an emergency. They also lacked properly-located smoke and carbon monoxide detectors.

In short, the conditions were a tragedy waiting to happen.

Despite the dangers, the only way San Luis Obispo city officials learned about the problem was when a student called the Fire Department to complain.

The Pine Creek lofts were a hidden safety hazard, and Cal Poly and Cuesta College student tenants didn’t seem fully aware of the dangers they posed. The property owners were all cited for the unsafe conditions, although some indicated the bedrooms were created before they acquired the condos, and they didn’t know they were not up to code.

San Luis Obispo city staff in 2013 discovered some Pine Creek Condominium tenants were living in illegally-converted loft bedrooms that were essentially fire traps due to their proximity to hot water heaters and furnaces, the ladders used to access the spaces and the windows that were too small for firefighters to use for rescues. Tribune file photo

“I can see how some people would think it’s unsafe,” one student tenant told Mustang News in 2013. “I chose to live up here, so I knew what I was getting into as far as the ladder (in the loft). The water heater is a little sketchy and I feel like there could be some modifications to make this room a little more safe.”

Pine Creek should have been a wake-up call. But in the years since, San Luis Obispo leaders have created no lasting policies to protect tenants or prevent similar situations from occurring in the future.

Pine Creek is just one example of the kinds of problems identified by a Tribune investigation into substandard rental housing, which found that many renters throughout San Luis Obispo County — including those in San Luis Obispo — continue to live in poor conditions and are too afraid of landlord retaliation to complain.

Many tenants also aren’t aware of their rights and must depend on spotty code enforcement that varies greatly from one community to another.

Although San Luis Obispo elected officials in 2015 approved a rental housing inspection program to ensure city renters had access to habitable housing, it didn’t last.

Pine Creek Condominium tenants living in illegally-converted loft bedrooms stored their clothes and other items in utility closets next to furnaces and hot water heaters. City of San Luis Obispo

And after the issue became a political wedge that ousted the mayor in 2016, a new council killed the rental inspection program once it became a source of controversy and outrage.

What happened to San Luis Obispo’s effort to protect tenants, and why did a public policy tool with good intentions fail here while it survives in cities like Santa Cruz and Fresno?

Three years after San Luis Obispo’s program died, it’s clear that elected officials — some of whom promised voters they would address substandard housing — have yet to create policies that ensure renters have access to safe, clean rentals.

“Complaint-based enforcement puts the burden on the tenant to speak up rather than the responsibility on the landlord to maintain a safe building. It leaves tenants at risk of being retaliated against, and fails to protect the most marginalized renters,” said Lucas Zucker, policy and communications director for the Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy (CAUSE), a nonprofit that works with tenants in Santa Barbara and Ventura counties.

Many Pine Creek Condominium tenants accessed their illegally-converted loft bedrooms using ladders, which are considered a safety hazard. City of San Luis Obispo

HOW SLO’S RENTAL HOUSING INSPECTION PROGRAM WORKED

After years of discussing rental housing inspections, the San Luis Obispo City Council approved a program in May 2015, and inspections began in 2016.

The program was designed to combat dangerous living situations like the ones that occurred at Pine Creek.

However, the idea of inspecting city rentals for safety issues was not new.

In fact, to date, San Luis Obispo has been conducting some form of rental inspections for more than 15 years. Since 2005, the city Fire Department has charged landlords an annual fee to conduct mandatory inspections of all multi-family housing complexes with more than three units to make sure they’re fire-safe and properly outfitted with smoke and carbon monoxide detectors.

But those inspections don’t apply to the city’s single-family and duplex units, which make up about 38% of the city’s rental stock, according to U.S. Census Bureau data.

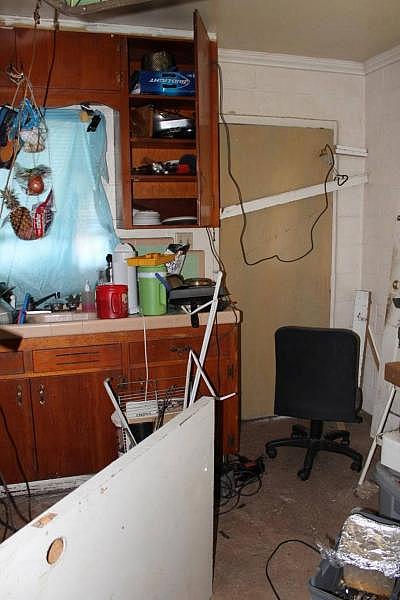

At the time, San Luis Obispo City Manager Derek Johnson — who was the community services director in 2015 when the City Council met to consider the program — showed council members photos of bedrooms located in garages without insulation and a housing unit powered by a single electrical wire strung through the doorknob.

“You may ask yourself, ‘Why do we need a rental housing inspection program? Why isn’t the city just going out and enforcing this?’” Johnson said at that meeting. “Well, these are all examples of things that we cannot see from the right-of-way. So, our proactive code enforcement program, absent a complaint and the permission from a property owner (to) go onto the property, we don’t discover these types of violations.”

SLO RENTAL HOUSING INSPECTION RESULTS

San Luis Obispo city staff had inspected 915 rental units, as of late January 2017. Only about 16% of units passed the first inspection, and the most common corrections were related to smoke and carbon monoxide detectors and electrical issues.

The program the council approved at that meeting mandated all city property owners register their rentals with the city and submit to inspections every three years.

The annual registration fee cost $65, and the inspections cost $185 every three years. The inspection fee covered the cost of two inspections, in case a follow-up was required.

Owners who passed the initial inspections could self-certify and inspect their own units for three years.

The inspections targeted basic habitability conditions, including locking doors, hot water, functioning heaters and plumbing that works properly.

By the end of January 2017, about 76% of rentals had registered with the city, and staff had conducted 915 inspections, according to a city staff report. About 16% of units required no corrections after the first inspection. The largest percentage of corrections were related to smoke and carbon monoxide detectors and electrical issues.

“Because of the fact that rents have been rising since 2003, and because of the shortage of housing, we have a terrible market situation,” then-Mayor Jan Marx said at a 2016 council meeting, according to a previous Tribune story. “Tenants, instead of standing up for themselves, because they’re really being exploited in many ways, they’re hanging onto status quo. ... My hope is that this program turns things around and makes them better.”

A collage of poor housing conditions shows a variety of substandard living situations in San Luis Obispo, including garbage piled up in a yard, overloaded electrical sockets, an illegal garage conversion and a unit powered by a single electrical wire strung through the doorknob. City of San Luis Obispo

WHAT WENT WRONG WITH THE INSPECTION PROGRAM?

Despite being winning the support of some students and groups like Residents for Quality Neighborhoods, the inspection program caused an uproar in San Luis Obispo, where 62% of residents are renters — 63% of whom are cost-burdened, meaning they spend 30% or more of their income on housing, according to Census data.

Landlords were unhappy about having to pay inspection fees and feared being forced to make expensive fixes to their properties.

“This is a massive government overreach and a Fourth Amendment violation,” said David Baldwin, a San Luis Obispo rental property owner, at a 2016 meeting, according to a previous Tribune story. “You have personally raised rents for tenants in the city. If you reverse this decision, you will lower rents for tenants.”

Tenants worried about losing their housing or having to pay higher rents if the program’s costs were passed on to them. They also feared they could be displaced if inspectors found significant violations or their landlords decided to take their units off the market rather than deal with inspections.

“That is the last thing anyone wants to do,” City Clerk Teresa Purrington, who was the city’s code enforcement supervisor in 2016, said of renter displacement at a council meeting that year. “We are prepared to work with the property owners to allow tenants to stay in their properties while repairs are being made as long as there are no immediate life safety issues in that unit.”

This photo, provided by the city as an example of health and safety concerns, shows excessive and hazardous electrical cords. City of San Luis Obispo

But for some San Luis Obispo tenants, the tight housing market meant they knowingly accepted poor housing because they couldn’t afford a better place to live. When they felt that housing was being threatened, they couldn’t support a program that would potentially cause them to lose their homes.

One tenant, Phil Hurst, told New Times in November 2016 he voluntarily moved out of the 116-year-old house he shared with a roommate after learning of the rental housing inspection program.

Hurst said worried his house wouldn’t pass the inspection, as it had “chipped paint and chipped counter tops. The heater didn’t work. There was no fume hood over the stove. Half the foundation was original, so the floors sagged. Shingles were missing on the roof.”

He was concerned his elderly landlady wouldn’t be able to make the repairs, and his roommate ended up leaving town.

“He couldn’t handle (the rent prices) anymore,” Hurst told New Times. “(Mayor) Marx is out of touch. She doesn’t know what it’s like to rent in SLO. You have to get to the core of the issue. Why are people living in garages? Because there’s nowhere to live.”

SLO INSPECTION PROGRAM REPEALED BUT NOT REPLACED

The rental housing inspection program became a major issue in the 2016 city election, and especially the race between Marx, a strong supporter, and now-Mayor Heidi Harmon, who campaigned against it.

Marx ultimately lost the election by just 47 votes. At a November 2016 news conference soon after Harmon was declared the new mayor, she vowed to replace the program. In March 2017, Harmon and the newly elected City Council repealed the inspections.

“We have to make sure people aren’t getting forced out of their homes,” Harmon said, according to a previous Tribune story. “But that doesn’t mean we do nothing afterward. We have to make sure tenants are living with basic safety conditions with how we move forward with any new policy.”

But Harmon has not kept her pledge to replace rental inspections with another policy.

San Luis Obispo mayor-elect Heidi Harmon, surrounded by election staff and supporters, delivers an address in front of City Hall after her election in 2016. Joe Johnston JJOHNSTON@THETRIBUNENEWS.COM

During Harmon’s four years in office, the city has not instituted any tenant protections, aside from raising fines for violating state and local housing codes.

And tenants still struggle to empower themselves in a market that favors landlords.

A San Luis Obispo code enforcement inspector told The Tribune there are still likely many renters who don’t understand their rights or are too afraid of landlord retaliation to complain about poor housing conditions.

Tenants who responded to The Tribune’s 2020 survey described paying for repairs out of pocket, feeling sick after living with mold, struggling to convince landlords to fix problems and feeling powerless in the face of a tight, expensive housing market.

Cal Poly students interviewed for a Mustang News article published in February 2017 — just before the rental housing inspection program was repealed — told the campus newspaper about living with soggy carpet wet from ceiling leaks, mold and pest infestations.

“Multiple times I’ve gone into the bathroom and I’ve found slugs. We’ve found frogs three times and I can hear frogs at night,” a student told Mustang News. “I think they’re probably living somewhere. We’ve also found a dead rat right inside the door that crawled out from the wall.”

A photo provided by the city as an example of health and safety concerns shows excessive and hazardous electrical cords. Courtesy city of San Luis Obispo

WHY HARMON OPPOSED INSPECTIONS

Harmon told The Tribune she opposed the rental inspection program in 2016 because “the vast majority of the community was very against it, and I thought it was very important to listen to that element of the community.”

“It seemed like one of those plans or programs or policies that had good intentions,” Harmon said. “When it was implemented, people thought it went too far.”

She said there’s “just no way (inspections) would come back anytime soon” and didn’t indicate any additional plans to improve conditions for renters.

Harmon instead put the responsibility on tenants to complain about problems and organize themselves to push for increased protections.

“Of course we’d want to know it if people are feeling unsafe in their housing,” she said.

In 2016, six candidates ran for San Luis Obispo City Council (from left: Mike Clark, Aaron Gomez, Christopher D. Lopez, Andy Pease, Brett Strickland and Mila Vujovich-La Barre). Two candidates vied for mayor (from right: Jan Marx and Heidi Harmon). The city’s rental housing inspection program was a huge issue in that year’s mayoral race. David Middlecamp DMIDDLECAMP@THETRIBUNENEWS.COM

Marx — who was elected to the City Council in 2020 after a four-year break from San Luis Obispo politics — said she sees the rental inspection program as “a noble effort, and it’s a shame it didn’t work out.”

She said city renters, especially Cal Poly and Cuesta College students, are still vulnerable, and landlords don’t currently have much of an incentive to improve their housing.

However, she’s accepted voters strongly opposed the program and said it’s an issue that’s “settled” for the city.

“It was a legitimate campaign issue,” Marx said. “It became a very emotional issue, and it became politicized in that people were saying it was invasion of privacy.”

Like Harmon, Marx pushed the burden for improving rental conditions onto tenants.

“The protection of tenants’ rights would have to come from the tenants, themselves, at this point,” she said.

UNIVERSITY BACKS RENTAL INSPECTIONS IN SANTA CRUZ

Although San Luis Obispo leaders ended rental housing inspections after less than two years, programs continue in other California cities, including Santa Cruz and Fresno. In both cities, the programs were enacted with the backing of powerful interests — a large public university in Santa Cruz and organized tenants in Fresno.

Santa Cruz, where 60% of residents are renters, is similar to San Luis Obispo in many ways. The city is on the coast and has a large student population, thanks to UC Santa Cruz.

The City Council passed a rental inspection program in 2010 as part of a settlement agreement between the university and and the city following a lawsuit over the school’s long-range development plan.

The university agreed to house 67% of new students, and city leaders agreed to “enact an ordinance regulating residential rental properties to make on-campus housing more attractive to students,” according to settlement highlights. UC Santa Cruz also paid a portion of the program’s initial costs.

Santa Cruz’s inspection program has slightly lower fees than San Luis Obispo’s and allows all landlords who own properties with no code violations in the past three years to self-certify without undergoing initial evaluations.

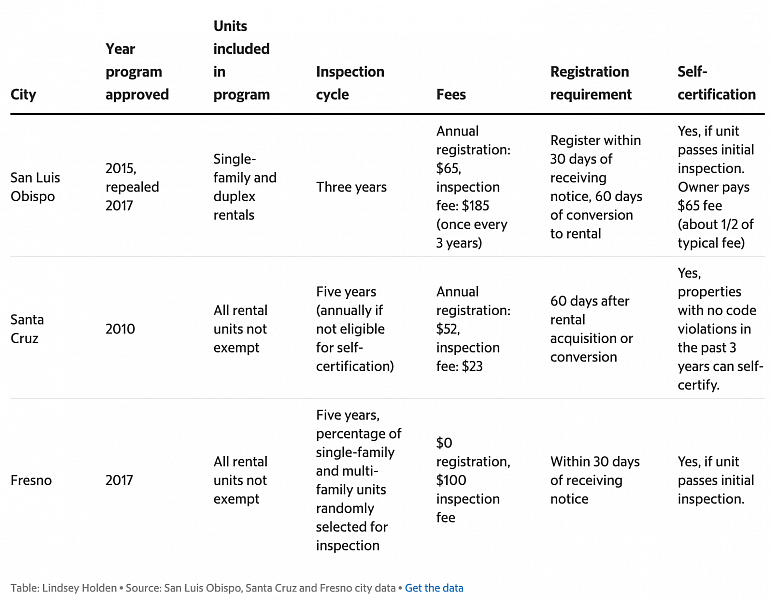

COMPARING 3 CALIFORNIA RENTAL HOUSING INSPECTION PROGRAMS

San Luis Obispo's rental housing inspection program shared similarities with those in Santa Cruz and Fresno, which continue to this day. All three programs required landlords to pay fees to support the programs, and they all allowed landlords to self-inspect their units.

The program has not been without controversy. It survived a 2010 landlord lawsuit when the Sixth Appellate District Court of California decided in the city’s favor in 2012.

And the City Council has continued to keep the program in place, in spite of some council members’ disapproval.

During fiscal year 2019, city staff inspected 3,715 units — about 14% of which passed the first time, and 86% of which required corrections, according to an October 2019 city staff report.

Laura Landry, city code compliance manager, said the program ensures residents live in units that meet minimum habitable standards and maintains the value of landlords’ properties.

“The program would be an advocate for those tenants who, for fear of retaliation, aren’t going to file a complaint form,” she said.

Even so, some tenant organizers feel the program hasn’t done enough to protect tenants, who lost a rent control ballot measure in 2018.

Reggie Meisler of the Democratic Socialists of America, Santa Cruz, said slumlords continue to persist, and tenants still lack the organized power they need to take on landlords.

“At the end of the day, a rental inspection program is only as good as your tenant advocacy,” Meisler said.

In 2016, city code enforcement inspector John Tanksley examines a broken heater — improperly hooked up and with bare wires exposed — at a Fresno apartment complex. The Fresno City Council approved a rental housing inspection program in 2017. JOHN WALKER JWALKER@FRESNOBEE.COM

FRESNO TENANTS ACHIEVE RENTAL INSPECTIONS AFTER LONG BATTLE

Fresno, where about 54% of residents are renters, is not an affluent coastal community like Santa Cruz and San Luis Obispo.

Housing is cheaper in the San Joaquin Valley, but renters still cope with substandard conditions and negligent landlords.

A turning point for the city and for organizers came in 2015, after thousands of low-income Summerset Village Apartments tenants were found to be living without heat, hot water or the ability to use their cooking stoves due to a gas line closure. One elderly resident later died of respiratory failure after coping with cold November weather in his unheated apartment.

Even before 2015, a local nonprofit, Faith in the Valley, had continuously posted photos on Facebook of blighted properties around the city.

Years of such organizing began to gain momentum after the publication of “Living in Misery,” a Fresno Bee series on substandard rentals and the Summerset crisis, said Andy Levine, Faith in the Valley deputy director.

“It’s not just cosmetic stuff,” Levine said of substandard rentals. “It’s truly life or death.”

He said it took a significant amount of public pressure to get city leaders to act. Organizers began to ask “how many more Summersets are there?” and recruited upstanding landlords to join them in taking action against slumlords.

Tong Cha holds a photo of her husband, Her Xa Lor, who died in January 2016 of complications from respiratory failure and pneumonia after falling ill when heat was turned off at Summerset Village Apartments in Fresno in November 2015. BONHIA LEE

“It actually was really simple,” Levine said. “Are you going to stand with the community, or are you going to stand with slumlords? Because you can’t have it both ways.”

It was important for the community organizing around rental inspections to involve tenants, who stood to benefit the most from the program, he said.

“It has to be led by the folks who are most affected by these experiences,” Levine said.

The City Council in 2017 voted to approve the city’s rental inspection program. Inspections are conducted every five years. There’s no charge for landlords to register their properties, and inspections cost $100.

Mayor Lee Brand, a Republican who worked for decades in the real estate industry, also championed the inspection program and oversaw its rollout before he opted not to seek another term in 2020.

“For elected officials, it’s our responsibility to ensure health and safety codes are followed,” he said.

Brand said his credibility with the business industry helped him bridge the gap between real estate interests and advocates.

“My answer to them was, ‘it is better to swallow a small regulatory pill now than wait a few more years and have to swallow a much larger regulatory pill,’” Brand told the Tribune in an email.

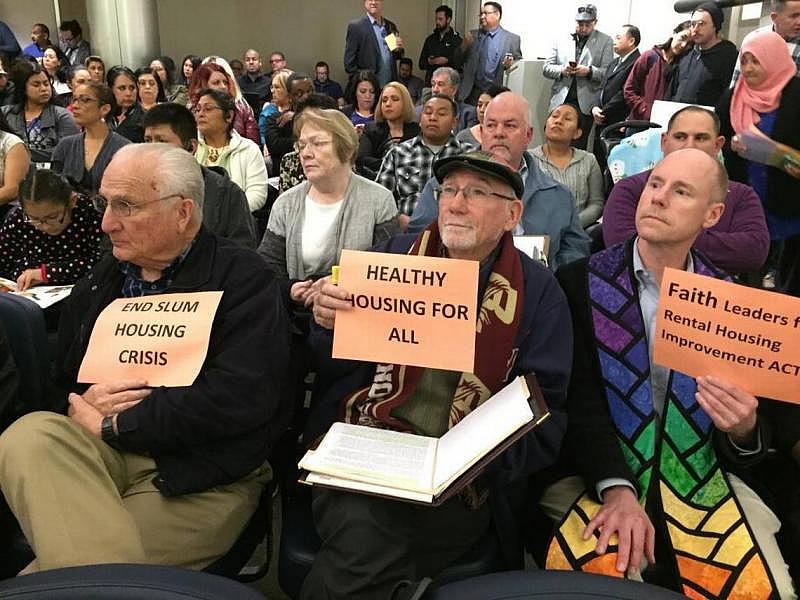

From left, St. Paul Catholic Newman Center deacon William Lucido, Roman Catholic Diocese of Fresno director of social ministry Jim Grant and Unitarian Universalist Church of Fresno Rev. Tim Kutzmark hold signs during a City Council meeting at which Fresno Mayor Lee Brand presented his rental housing inspection plan on Thursday, Feb. 2, 2017, at City Hall in Fresno. SILVIA FLORES SFLORES@FRESNNOBEE.COM

TENANT ORGANIZING IN SAN LUIS OBISPO COUNTY

Three years after San Luis Obispo’s rental housing inspection program was repealed, some local organizers are beginning to push for better housing policy.

In April, spurred by the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic, residents created the Rent and Mortgage Relief Coalition of San Luis Obispo County, said Dona Hare Price of Bend the Arc SLO and the San Luis Obispo Democratic Party.

The group lobbied city councils to use CARES Act funds to provide direct assistance and continue to support statewide efforts to push for COVID-19 eviction protections, Price said.

Price said she’s hoping to create a Tenants’ Collaborative to “organize tenants so they know their rights, are protected, have a place to share information and resources, and can advocate for local policy that ensures there is affordable, safe and secure housing during the pandemic and our uncertain future.”

“Most renters in SLO County work in service jobs and agriculture,” Price said. “Renters are overwhelmingly low-wage workers, people of color, young people and immigrants. These are the people most directly affected by the economic and health-related impacts of the pandemic. They should not have to choose between food, medicine and housing. They should not have to sacrifice their health and safety just to pay the rent.”

Organizing tenants is essential to creating policy change, especially because the real estate industry and property owners are so well-equipped to lobby local leaders, said Zucker, from the Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy.

“At the end of the day, politics kind of responds to organized power and organized voice,” Zucker said.

Local housing politics build on existing power imbalances between younger and older people, wealthy and low-income residents and immigrants and non-immigrants, he said.

“We really act as a bridge between folks who are otherwise marginalized from the political system and the local government,” Zucker said.

CAUSE helps correct these imbalances by preparing people to speak at meetings, facilitating conversations with City Council members and providing legal aid, so renters know they have an organization backing them.

“Everyone’s afraid, but when they see other who are taking action despite that fear, that emboldens them to take that action, too,” Zucker said.

This story was produced with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, the Center’s engagement editor, Danielle Fox, and KTAS-Telemundo.

[This story was originally published by The Tribune.]