Two neighborhoods in S.F. struggle with the aftermath of a citywide RV crackdown — and it’s about to get worse

The story was co-published with El Tecolote as part of the 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

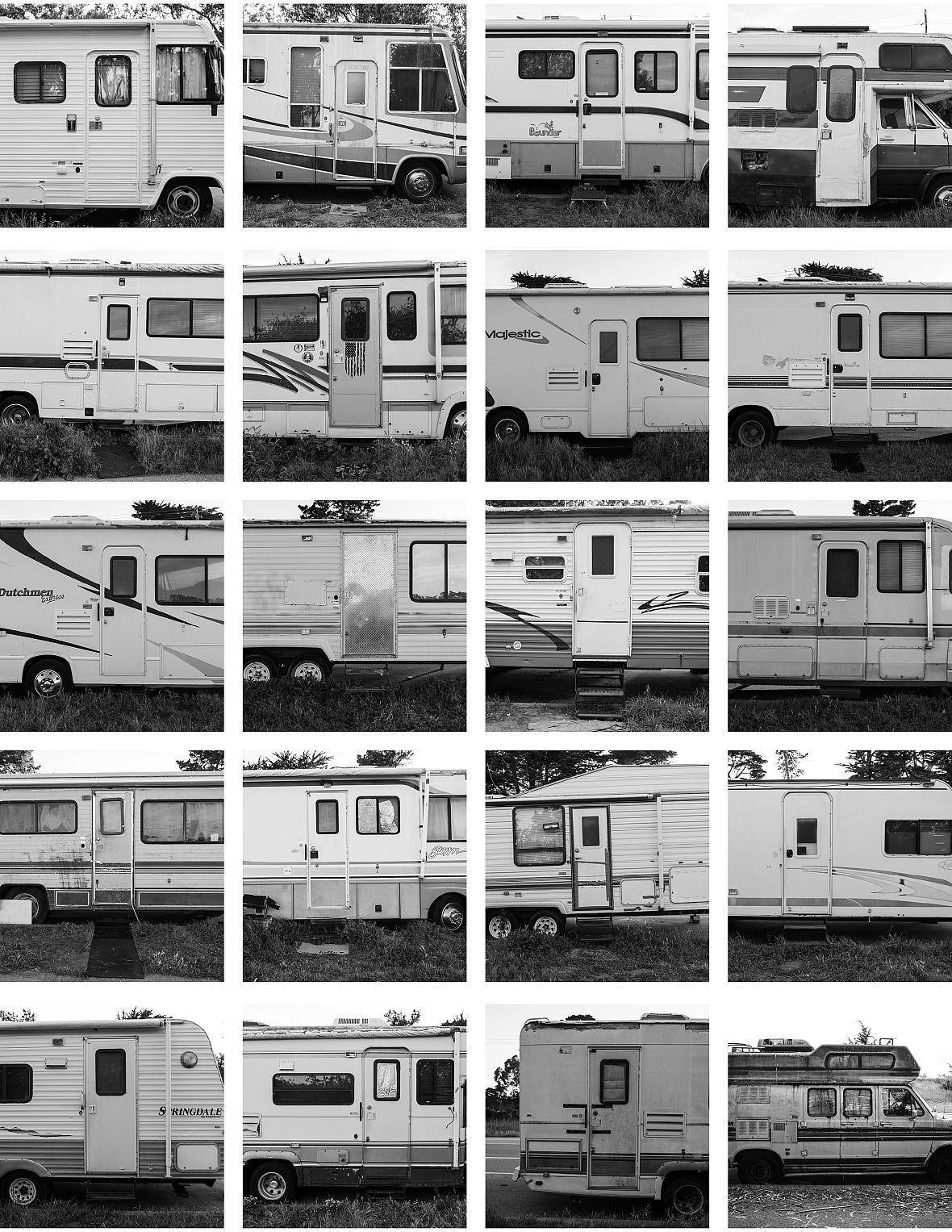

As San Francisco steps up efforts to curb vehicular homelessness, safe parking options for RV residents have dwindled. Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote / CatchLight Local

Along John Muir Drive, a winding road in San Francisco’s quiet Lake Merced neighborhood, more than a dozen RVs line the curb. Inside one of them, Jessica Cuevas, 32, lives with her eight-year-old son. After being evicted from her $3,800-a-month rental in late January, she bought an RV on Facebook Marketplace and parked near her son’s school in the Bayview. When parking tickets began piling up, she moved across the city to Lake Merced, joining other RV residents who, once again, may soon have to leave, this time having nowhere else to go.

As San Francisco steps up efforts to curb vehicular homelessness, safe parking options for RV residents have dwindled. The crisis, which disproportionately impacts Latino immigrants, has pushed longtime residents hit hard by pandemic job loss and newcomers seeking sanctuary into two distinct neighborhoods: Lake Merced and the Bayview.

More than a dozen RVs line an industrial street in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, Calif., on Aug. 25, 2025, where many working-class immigrant families live inside their vehicles. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote / CatchLight Local

The Lakewood Apartments serve as a backdrop to a row of RVs parked along the street near Lake Merced in San Francisco, Calif., on April 9, 2025. Some neighbors have voiced concerns about the RVs in online forums such as Reddit.

At the same time, more people are turning to oversized vehicles for shelter as San Francisco’s cost of living soars. Driven onto the same few streets, many RV residents have formed small communities of support.

Now, a new citywide policy could decide the future of hundreds of people and families who call RVs home. Starting November 1, 2025, San Francisco will enforce a two-hour parking limit for large vehicles. Residents must obtain a Large Vehicle Refuge Permit or face tickets and towing. City officials say the program will connect eligible residents to housing assistance, but advocates warn it will uproot families and worsen conditions for working-class immigrants, seniors and people with disabilities already weathering the physical and mental health toll of displacement.

Over the past year, El Tecolote has documented the informal support systems forged by RV residents in Lake Merced and the Bayview in the absence of city aid. Firsthand accounts and public records reveal that, despite the promised support, the city’s upcoming crackdown threatens to dismantle the fragile stability these households have found.

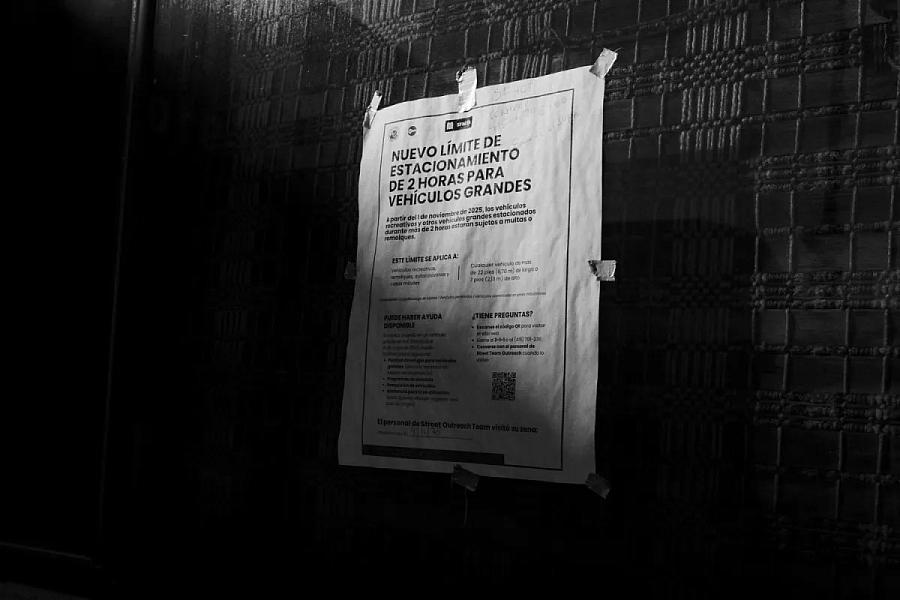

Notices of the two-hour parking enforcement from the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency were taped onto people’s RVs in the Bayview neighborhood, in San Francisco, Calif., on Sept. 19, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote / CatchLight Local

This isn’t forever: Families find refuge in Lake Merced

When Cuevas worked as a DoorDash delivery driver last year, she often drove past dozens of parked RVs around Lake Merced. The Mexican mother worked three jobs and shared a Visitacion Valley home with two roommates to cover $3,800 rent. She had already been homeless once, when she first moved to the Bay Area in 2018 with a pending asylum application. After time in San Mateo County’s shelter system, a social worker helped her find housing in San Francisco.

By late January, an eviction over missed rent payments pushed her family back to the streets. Cuevas bought an RV and started parking near her eight-year-old son’s school in the Bayview, moving every 72 hours to avoid tickets. As the citations piled up, Cuevas remembered the motorhomes she’d seen in Lake Merced, and headed west.

Jessica Cuevas, 32, stands outside her RV near Lake Merced holding her two guinea pigs in San Francisco, Calif., on April 9, 2025. “I like staying on this street because it feels safer than the Bayview, where we stayed for a short time,” she said. “It’s been really difficult to get any type of resources.”

In March, Cuevas found a spot on John Muir Drive, a wide, quiet street facing the lake where dozens of other RVs were parked.

“We’re still here,” Cuevas said. “We’re trying to look for a better place. But we have to wait.”

Her RV is small and poorly insulated, and rain seeps through the roof. Inside, a single mattress fills most of the floor, and a plastic box holds her son’s two guinea pigs, Pepe and Greñas. Without electricity or plumbing, they rely on the park’s public restrooms and a propane stove.

This kind of unstable housing puts residents at greater risk of poor health outcomes, including respiratory and cardiac diseases, public health experts warn. It also makes it harder to manage chronic conditions.

A city parking restriction sign stands along John Muir Drive in the Lake Merced neighborhood of San Francisco, Calif., on April 9, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote / CatchLight Local

San Francisco’s promise of housing support to RV residents is what Cuevas says she needs, though those options seem far from reach. She’s been on the city’s backlogged family-shelter waitlist since January. In June, the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing reported that 295 families were waiting for shelter.

For now, Lake Merced feels more peaceful than anywhere else she’s parked. The area is quiet, aside for chirping birds, and the occasional car driving by. Between the line of RVs and the lake, residents take evening strolls along a walking path.

Many parked along the road have formed a sense of community. They look out for one another — Cuevas said she once drove a neighbor to the hospital after noticing she was limping — and work together to keep the area clean.

“This place is nice and we try to take care of it, because they’re letting us stay here,” said Rubén, a 23-year-old Mexican immigrant who lives a few RVs down. Unlike Cuevas, Rubén chose to move out of a shared apartment and invest in an RV, saving the wages he earns from a street-repavement company.

The work boots of Rubén, 23, a Mexican immigrant who lives in an RV near Lake Merced, an area that has become a refuge for displaced working families in San Francisco, Calif., on April 9, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

Residents are able to park on John Muir Drive for months largely due to sparse enforcement, moving their vehicles only for biweekly street sweeping.

Yet even that schedule brings stress, affecting their mental health. Yuri S., 40, watches her one-year-old daughter during the day while her husband works, so she’s often in charge of moving the RV every other Monday, despite not knowing how to drive. When spaces fill up after street sweeping, she sometimes has to park in other parts of Lake Merced that feel less safe, with heavier traffic and unfamiliar neighbors.

“Sometimes I just want to leave as fast as I can,” said Yuri, whose family was pushed out of a shared apartment in Daly City after having a baby last October. “I’m not used to this. Living here, in the United States, is completely different from anything I was used to.”

Yuri S., 40, stands outside her RV near Lake Merced, an area that has become a parking refuge for working families in San Francisco, Calif., on April 9, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote / CatchLight Local

Echoes of a displaced community

Some residents now parked along John Muir Drive had previously spent years in even more established RV communities nearby Winston Drive and Lake Merced Boulevard. There, they had systems in place to discard water waste, organize trash pickups and coordinate childcare.

But last summer, the tight-knit community of predominantly Latino families was dispersed to different parts of the city after one of San Francisco’s most controversial crackdowns. According to Lukas Illa, an organizer with the Coalition on Homelessness, the displacement placed them in even more precarious situations.

A row of RVs, where many working immigrant families live, lines a street near Lake Merced in San Francisco, Calif., on April 9, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote / CatchLight Local

“Sweeps are not only a means to displace people from a sidewalk, it is a means to break down communities and break down political power,” Illa told El Tecolote. “It breaks down communication channels. It breaks down the community of trust and resource sharing.”

Illa said the mass eviction of a working-class community of families with children on Winston Drive exposed the limits of the city’s goodwill to find compassionate solutions. “We had the most humanizing population,” he said. “And still, nothing was done. It was seen as acceptable to displace them.”

District 7 Supervisor Myrna Melgar, who represents the neighborhood, has since become a leading voice in regulating and banning RVs citywide. Melgar has framed enforcement as a way to protect RV residents, who she says have faced harassment, vandalism and frequent calls to law enforcement, including Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

Juan Sebastián, 25, a newcomer from Colombia, shows his neck tattoo in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, Calif., on April 24, 2025. “I carried my two daughters in front of me with my suitcase on my back,” Sebastián said, recalling his migration through the Darién Gap from Colombia. He and his wife later saved enough money to apply for political asylum and obtain Social Security numbers. “It’s all been thanks to the RV,” he said.

Pablo Unzueta

Daniela, 37, raises her hand toward the sun in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, Calif., on Aug. 26, 2025. She lives alone with her four dogs across the street from an Amazon warehouse. Daniela fled gang violence in El Salvador in 2015 and was granted political asylum in the United States, but later found herself trapped in street life.

“We do not have a system to not just regulate but also support these families in an adequate way,” said Melgar on July 15, ahead of the vote to approve the new RV policy. "I think it's on us to build the system to support people to success, and not pretend that by leaving them on the streets we are doing the progressive thing."

Even in Lake Merced, where complaints from neighbors are driving an uptick in enforcement on certain streets, RV residents have continued to park and accrue tickets. Vidal Drive, for instance, limits parking to four hours without a permit but remains a refuge for residents like Beriuska Acosta.

“The tickets are piling up, but we have nowhere else to park,” said Acosta. Each parking ticket costs $102. “I get stressed out when I see the parking officers coming because you don’t know who you are going to get that day.”

RVs are parked in front of an Amazon warehouse in the industrial Bayview neighborhood where a concentration of families are living inside their RVs, many who are working immigrants, in San Francisco, Calif., on Jan. 17, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

In the Bayview, RV residents are pushed to the brink

While Lake Merced’s RVs sit near water and family housing, those in Bayview–Hunters Point make do in industrial corridors lined with warehouses and empty lots. Along Jerrold and Barneveld avenues, rows of RVs sit wheel-to-wheel. Children’s bikes and barbecue grills rest outside. On Toland Street, a massive Amazon logo looms over the rows of vehicular homes.

For Laura C., 37, living in an RV is the only option for her family. She rents her vehicle for $1,000 a month from another resident and has parked along the same Bayview avenue for months.

Inside the RV the Clavejo family rents for $1,000 a month in the industrial Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, Calif., on April 3, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote / CatchLight Local

“On one occasion, the city came to clear us out,” Laura said. “But to tell you the truth, we came back. There is nowhere else to park.”

District 10 Supervisor Shaman Walton, who oversees the Bayview, was one of two supervisors to vote against the new RV policy, arguing that an enforcement-first approach won’t solve the housing crisis that made RV living necessary.

“To say that someone living in a vehicle does not have a home is malicious when they have no other form of shelter,” said Walton during the board’s vote. “This legislation is alluding to supporting brick and mortar as the only possible home in the most expensive city on the planet.”

Laura C., 37, pours a spoonful of Gatorade into a cup while her two children eat lunch inside their RV in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, Calif., on April 3, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote / CatchLight Local

With 55% of the city’s RVs parked in the Bayview, Supervisor Walton’s district is the epicenter of the city's RV crisis. In emails obtained by El Tecolote, residents described RVs blocking hydrants and generating trash and noise, which they fear deters potential tenants. Despite numerous 311 reports, many cases are quickly closed as “invalid” or “canceled,” fueling accusations of unequal enforcement compared with wealthier Lake Merced.

Meanwhile, along a number of streets in the Bayview, RV neighbors say they help each other find jobs, resources and care for each other’s pets. Some, like Laura, lend their shower or kitchen to neighbors living in cars.

In September, the SFMTA began taping notices on the windshields of these RVs, warning that vehicles longer than 22 feet or taller than seven feet will risk being towed. The flyers invited residents to informational events and permit workshops.

Laura C., 37, checks her DoorDash app from her car in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, Calif., on April 3, 2025.

The agency is offering six-month parking permits for people who were found parked in the city on May 31, as well as a limited number of housing subsidies. Permits could be revoked if residents decline shelter services. The city will also have an optional buyback program, paying $175 per linear foot — $1,000 upfront, with the remainder after residents secure housing.

Laura and her husband said they feel reassured by the permit but are anxious that they might be required to give up their RV to qualify for housing, a rumor that has circled among RV communities. A city spokesperson with the Department of Emergency Management clarified in an email that residents can keep their RVs, though they must move them to storage or parking outside the city once the ban begins.

Still, Laura worries that housing subsidies won’t provide lasting relief. She and her husband have struggled finding steady work that could help them afford a full month’s rent, and this form of rental assistance is time limited.

“You adapt to a place,” Laura said. “We’ve already adapted to the calmness here. So going to a different place is difficult because you’re not sure if you can trust it, you can’t leave your children alone.”

The toll of displacement on fragile communities

As the ban looms closer, many RV residents feel mounting anxiety about their future. Lupe Velez, communications director at the Coalition on Homelessness, says some elderly immigrants she’s spoken with are so stressed they can’t sleep, unsure if they’ll qualify for permits.

“There's really just so many barriers that they're facing just to receive this information: cultural, language, generational,” she said. “It’s just really devastating.”

For some residents, giving up their vehicle would mean surrendering their only source of stability. And frequent displacement can disrupt access to medication and healthcare visits, as well as take a steep mental toll. A 2021 study on Oakland’s RV population, for instance, found that RV residents were often reluctant to seek healthcare or social services because they feared their vehicles might be towed while they were gone.

Parking restriction signs are posted in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, Calif., on Sept. 19, 2025. According to RV residents, city crews arrived shortly after to clear the area.

Notices announcing the new two-hour parking enforcement by the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency are taped to RVs in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, Calif., on Sept. 19, 2025.

For Daniela, 37, who lost most of her belongings during a tent sweep five years ago, those fears are constant. She fears leaving her RV for too long, worried that it might get towed. She can’t fathom giving it up for a shelter bed, leaving her five pet dogs behind.

“Sometimes I have enough to eat, sometimes I don’t,” said Daniela, who parks her RV in the Bayview, by an Amazon warehouse. “I’m always worried about the police coming and taking away my home because it’s the only thing I have.”

Others are cautiously optimistic. Asylum seekers Alexander, 33, and his wife live with their dog in an RV. Increased enforcement pushed them from Vidal Drive to John Muir Drive, but they’re considering the city’s permit program and even the city’s buyback offer.

Daniela, 37, stands outside in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, Calif., on Aug. 26, 2025. She lives alone with her four dogs across the street from an Amazon warehouse. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote / CatchLight Local

“It’s nice that they’re giving us opportunities,” Alexander told El Tecolote. “That they’re not just putting rules but that they’re giving us a way to move forward.”

A few vehicles down, Mario and Nancy Guardin are more skeptical. They plan to apply for the permit but are wary of selling their RV, worried that once housing subsidies expire, they’ll face homelessness again. “With a safe parking site they would be able to solve all these problems,” said Mario. “But they don’t want that.”

With an enforcement deadline looming, the city is deciding where to place the new two-hour parking signs. Mayoral staffer Eufern Pan advised the SFMTA in an email to base the locations on four factors: where RVs are concentrated, where constituents complain most, 311 data, and input from police and parking officers who work on homelessness.

Samir, 8, walks past the RV where he lives with his family in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, Calif., on April 24, 2025. He attends Buena Vista Horace Mann K-8 Community School, which operates an overnight shelter for students and families experiencing homelessness. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote / CatchLight Local

For the dense communities of families living in RVs in Lake Merced and the Bayview, it’s unclear whether the new policy will stabilize their lives with more housing opportunities, or uproot them entirely through constant tows.

“They have consolidated the RVs to two different spots. It's the Bayview, it's Lake Merced,” said Illa. “[It’ll make it easy] for cops to monitor every two hours.”

Illa says a ban on large RVs, a “visible sign of poverty,” will only encourage housed residents to report RVs in their neighborhoods and push families to seek refuge in cars and smaller vehicles.

“It's a lot harder to stay vehicularly housed in an RV versus like a sedan because the image of an RV is so stigmatized, is so hyper policed, that it is reported the second that it is seen,” Illa said.

From the living room of her RV in the Bayview, Laura looks out over an industrial landscape. Her eyes widen when she thinks about a backup plan.

“This is our home. If they take our homes we will end up in the street,” she asserted. “For me, this is my home.”

Laura C., 37, looks out from the RV she rents for $1,000 a month in the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, Calif., on April 24, 2025. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote / CatchLight Local

This project was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California”, a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.