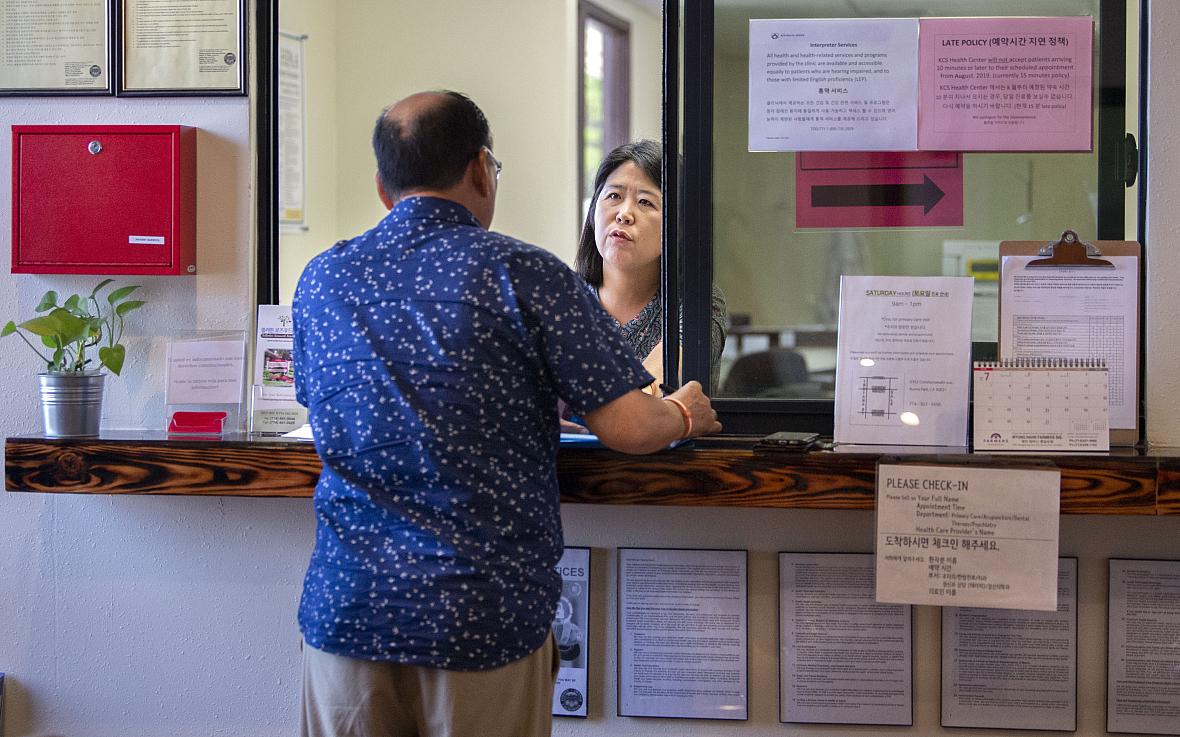

Undocumented, uninsured Korean Americans find safe havens in nonprofit clinics

Mindy Schauer, Orange County Register/SCNG

Steve Kang says he's just lucky he didn't fall sick during his first 15 years in the United States.

The 48-year-old came to Southern California from South Korea on a travel visa in 2002. He says he stayed for what he believed would be opportunities to improve his life. But he's remained undocumented and without health insurance since he arrived.

In 2017, though, he found the Kheir Clinic in Los Angeles' Koreatown, which largely serves those in need in the surrounding community.

It was here that Kang was diagnosed with prediabetes and high cholesterol, something he might never have known had he not walked into the clinic.

"I'd never seen the inside of a hospital or doctor's office until two years ago when I came here," he said. "I just couldn't afford to go to a doctor."

Kang said he makes about $2,000 a month working as a liquor store clerk. For him and thousands of other undocumented and uninsured Korean Americans in California who have no other alternatives but to pay out of pocket for health care, these clinics have been a godsend.

Korean Americans constitute the highest percentage of undocumented immigrants in the Asian American community, said Tom Wong, associate professor of political science at UC San Diego who served as an adviser to the White House Initiative on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the Obama administration.

Data on undocumented and uninsured Korean Americans are scarce, but based on his research and an unpublished white paper for the state of California, Wong estimated there are 49,092 undocumented Koreans in California. About 30% don't have health insurance, he said.

Gains from the ACA

While the picture is still bleak, the lack of health care access among Korean immigrants was several times worse before the passage of the Affordable Care Act, said Ellen Ahn, executive director of Korean Community Services in Buena Park, which operates two clinics in the city and serves about 3,500 patients — about 60% of them Korean.

Before the ACA, 90% of the patients who came to the clinic were uninsured. Now, Ahn said, that number has dropped to 20% after a large number of those who are legal residents but couldn’t afford health insurance were able to enroll in Medi-Cal, the state’s health program for low-income residents.

"Now, most of our patients are covered by Medi-Cal," she said.

It's a similar scenario at the Kheir Center, the largest facility serving Korean Americans in the country, said director Erin Pak. Its four clinics and one adult day care center, serve about 13,000 people and more than 60,000 visits a year, she said.

Kheir’s clinics in Los Angeles and the two clinics operated by Korean Community Services in Orange County are federally qualified health centers, which are community-based health care providers that receive federal funding to provide primary care and other services in underserved areas.

Kheir even runs a minivan pickup service for seniors, and recently added the service for undocumented patients who are afraid to use public transportation for fear of raids or arrests, Pak said. For those here legally, the challenges of lack of coverage are now being replaced by fears surrounding the Trump administration's "public charge" rule, she said. If implemented, it could deny green cards to immigrants who use social services such as food stamps, cash assistance or public housing.

‘Public charge’ fears grow

Since the Trump administration introduced the proposal earlier this year, several patients with Medi-Cal have stopped coming to the clinic, Pak said. The public charge rule had been set to go into effect on Oct. 15 but is currently blocked by the courts.

"When we first heard about public charge, we had several patients come in with fruits and gifts for their primary care physicians and say goodbye," she said. "People who are eligible for Medi-Cal are not enrolling, and those who are on Medi-Cal are asking how they can disenroll. They say they don't want their names to be in the system as receiving social services. It's heartbreaking."

For undocumented patients such as Kang, the threat of an immigration raid looms. Kang said he likes to stay positive and live in the moment.

“Right now, I have to take care of my health,” he said. “I can’t worry about what will or might happen. I have to hope for the best.”

But such optimism, Pak said, is rare among the undocumented population, almost all of whom receive care at the clinic through Los Angeles County's My Health LA program, which is free for individuals and families who don't have or cannot get health insurance, regardless of their immigration status. A new state law will expand Medi-Cal access to undocumented immigrants under age 26, but anyone older will remain ineligible.

Fear and hopelessness among the undocumented Korean community also has contributed to higher suicide rates, said Pak, who gave the recent example of a man with stage 4 stomach cancer who took his own life.

Undocumented and uninsured people are particularly flummoxed when they receive a cancer diagnosis, said Ahn, who added that in many cases, the cancer goes undiagnosed or untreated.

Ahn's Buena Park clinic is helping a 52-year-old woman who was diagnosed four years ago with breast cancer but never sought or received treatment.

"Language was a huge barrier," she said. "She did not know where to go or what to do. She didn't know whom to ask."

By the time she came to Ahn's clinic, the woman, who is single, had developed stage 4 cancer that had spread to her spine. She is getting chemotherapy now, though it may be too little too late, Ahn said.

"But, at least now she says she is grateful that she is being helped and that someone cares about her," she said. "Had she come to us earlier, she could've been cured. It's really sad."

Returning home for treatment

In some cases, undocumented individuals choose to return to South Korea for treatment, said Karen Park, health care coordinator and navigator at Korean Community Services.

"Cancer is really a death sentence for our undocumented folks," she said.

Park gave the example of one patient at the clinic, an undocumented and uninsured woman in her 70s who lives in Orange County with her grown children.

"Doctors found a lump on her breast," she said. "She would come here crying every day. She eventually went to Korea for nine months, got her cancer treatment and came back."

Park doesn't know how the woman reentered the United States but said, "people seem to find a way."

Some of the barriers to health care in this community are self-imposed. In the Korean community, there is a stigma attached not just to mental illnesses but even diseases such as cancer, Ahn said.

"Even for us to broach the topic of health care is very hard in this community," she said. "It's a combination of fear, shame and face-saving. They don't want to stand out."

A vast majority of those who are undocumented in the Korean community in Southern California are well-educated, Ahn said.

"Most of them come here on a tourist, student or work visa and end up overstaying," she said. "So, for someone who is undocumented and uninsured, they have a lot to lose."

The language barrier has posed another challenge for the Korean community, particularly for those who are middle-aged or seniors. Park said she has found patients who don't file their tax returns because they struggle with the language and therefore cannot access health benefits through Medicare or Medi-Cal.

Spreading the word about services

Korean-language media have played a significant role in spreading the word about health services provided by both Southern California clinics. Clinic staff members write columns in newspapers. They answer questions during live radio calls. They also put out public service announcements on radio and television.

Kang said he finally found Kheir through a newspaper ad, despite living just a few miles from the clinic for 13 years.

The key to helping more in the community access health care is to get the word out in as many ways as possible, Pak said.

"In spite of the challenges and barriers they've faced, Koreans still believe America is the greatest country in the world," Pak said. "They take all these risks to come here. Yet they are a culturally and linguistically isolated population. Right now, fear is pervasive.

"And we need to do our part to eradicate this fear with facts."

Follow the USC Center for Health Journalism Collaborative series "Uncovered California" here.