The Unseen Mental Health Challenges of Chinese Undocumented Immigrants

The story was co-published with World Journal as part of the 2024 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

Undocumented immigrants lining up to receive relief supplies in Jacumba Hot Springs, San Diego County

Jian Zhao/World Journal

When talking about undocumented immigrants, people often envision a group of people crossing borders, piling into border patrol buses and scattering and fading from sight. For these immigrants, however, the trauma of crossing borders can strain their mental health, and these changes seem to be visible only to themselves.

There is limited research on mental health issues among undocumented immigrants, with even fewer studies focusing on Chinese immigrants.

Alyssa Ghirardelli, chief research scientist at the National Opinion Research Center, pointed out the difficulties in collecting mental health data from undocumented interviewees, who often fear being questioned due to their immigration status.

But that doesn’t mean these immigrants don’t face considerable challenges. Immigrants often face past traumas, current survival challenges, and future uncertainties. Factors such as low levels of English proficiency, high occupational stress, discrimination, immigration challenges, and cultural differences can result in significant mental stress upon arrival for Chinese undocumented immigrants.

Walking in the dark

"I often talk to myself. It feels like walking alone on a dark road, unable to see anything, yet still whistling. It's not that I feel happy in the darkness; I just do it to bolster my courage," said Yuan Yang, a 55-year-old Chinese immigrant, who has been in the United States for 12 years.

Yuan Yang lives with 9 roommates in a "family hotel" located in Monterey Park. His bed is separated from the neighboring bed by a wooden board.

Photo courtesy Yuan Yang

Even after all these years, he still resides in a "family hotel" (a shared rental not requiring tenants’ identity verification) in Monterey Park, and where he pays a monthly rent of $550. He lives with strangers, separated from his neighboring bed by only a wooden board. His personal belongings can only be stored under the bed or piled up on the corner of the bed.

Yuan Yang has been relying on temporary jobs to make a living, such as giving massages, caring for the elderly, or doing day labor on construction sites. However, as he gets older, finding a job has become extremely difficult for him. He struggles to survive, often borrowing money from other workers and relying heavily on food banks and donations for sustenance.

Because Yuan Yang was unable to pay for an immigration lawyer, he had to submit his immigration documents independently without fully understanding the rules. He still hasn't heard back about his application. And over the years, he has had to work without permits to make a living, which means employment under exploitative conditions or without legal protections.

“As I grow older, I find it increasingly difficult to do physical labor. Every day I think about where my pension will come from without legal immigration status. These questions have been haunting me for years, weighing heavily on my mind. I can't find a way out, and I feel my mental state is often distorted."

Yuan has attempted to find solace in religion. He first explored Caodaism, then turned to Tibetan Buddhism. He believes that having faith might prevent him from falling apart mentally. "But in reality, my heart can never find peace. None of these fundamental issues can be resolved."

Yuan has also tried to seek help from a psychologist, but making appointments at mental health clinics is difficult. After months of waiting, he finally saw a therapist. But he gave up quickly. Yuan felt that due to their vastly different experiences and ethnic backgrounds, many therapists struggle to understand what he is going through.

Over the years, Yuan said he met quite a few roommates with mental health issues. One of them, who slept in the bed next to his, was a fervent religious believer who always carried a machete. Another roommate, a woman in her fifties, shared a room with Yuan and would sometimes scream after the lights were turned off, saying she wanted to kill someone. Yet another middle-aged man, usually quiet, constantly smoked with a furrowed brow. One day in early 2022, he collapsed in the bathroom and died after being rushed to the hospital.

According to 2019 figures from the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), the estimated number of undocumented immigrants in California is around 2.74 million, accounting for approximately 4% of the state's total population.

A group of Chinese migrants who just crossed the US-Mexico border in San Diego county.

Jian Zhao/World Journal

The lack of research does disservice to undocumented immigrants who contribute to the American society and the economy. Kent Wong, project director for labor and community partnerships at UCLA Labor Center, notes that there are 11 million undocumented immigrants living in the United States. During the pandemic, many were celebrated as "essential workers" who play a vital role working on the frontlines to provide services for our very survival. This includes workers who plant and pick our food, who care for our children and elderly, and who work in service, manufacturing, and construction jobs necessary for our society to thrive. Without in-depth research on the mental health of this group, it is difficult to develop a broader understanding of their mental state.

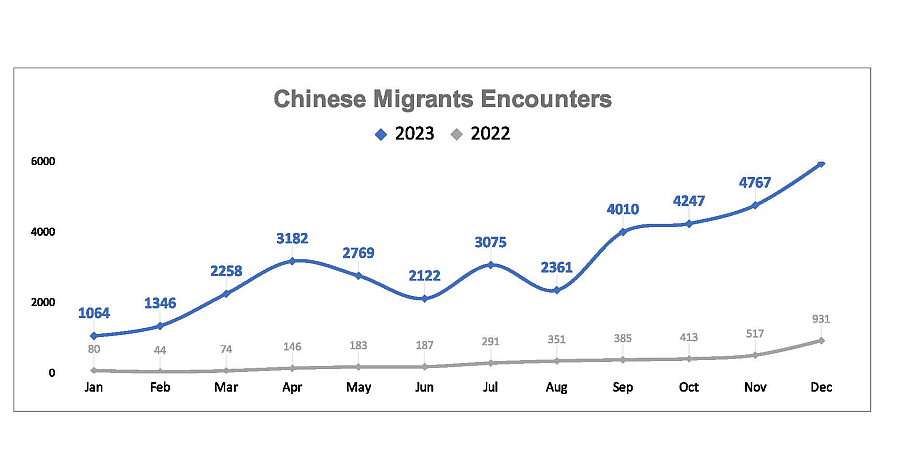

MPI data also shows that there are approximately 390,000 Chinese undocumented immigrants in the United States, with over 110,000 residing in California. This figure does not include the surge of Chinese immigrants who crossed the U.S.-Mexico border after the pandemic.

Chinese migrants have surged at the U.S.- Mexico border after the pandemic. Line chart: Jian Zhao/World Journal

Chinese migrants have surged at the U.S.- Mexico border after the pandemic.

A 2021 review of the existing research on the mental health of undocumented immigrants showed that discrimination, cultural adaptation stress, traumatic events, limited social services and healthcare resources, isolation, exploitation, and fear of immigration law enforcement have long been seen as prominent difficulties for illegal immigrants.

Hope Delivered by Universal Healthcare

The good news is that as of January 1, 2024, California has expanded public health care coverage by, providing comprehensive Medi-Cal coverage to low-income residents aged 26 to 49, regardless of immigration status. This policy means that qualifying undocumented immigrants in California can now obtain health insurance that covers mental health care.

Chinese migrants at DingPangZi Square in Monterey Park

Jian Zhao/World Journal

However, many people who now qualify don’t know about the policy change. After visiting DingPangzi Square in Monterey Park, a gathering place for Chinese undocumented immigrants in Los Angeles County, only about 20% of undocumented immigrants informally surveyed had heard of California's new health care policy. About half of those interviewed believed that joining Medi-Cal could affect their immigration applications (it does not). Some even said they would rather forgo benefits than take risks.

Dr. Stephen Denq, CEO of Tzu Chi Medical Foundation, an NGO providing healthcare service to disadvantaged people, says that for undocumented immigrants, survival is the priority. They focus more on livelihood and basic needs than mental health issues. "Most of them lack the motivation to seek help.” Denq said. But, as Yang stated, even when they do try to seek help there are too many barriers, including cost, time and cultural sensitivity.

Father of Three Daughters

Chinese immigrant Mr. Huang, 35, has three daughters — a pair of 8-year-old twins, and their 9-year-old sister. Mr. Huang, who declined to share his full name out of privacy concerns, had long planned to come to the United States, but his U.S. visa was rejected twice during the pandemic. So, he said farewell to his daughters and spent $20,000 to travel from Latin America to the United States, hoping to create a better future for his family.

On the US-Mexico border, in in Jacumba Hot Springs, some Chinese parents said they chose this way of entry to provide their children with better educational opportunities.

Jian Zhao/World Journal

However, setbacks and breakdowns became routine after arriving — high rents, limited job opportunities, and constant stress. Mr. Huang not only works long hours at a restaurant every day but also faces criticism from employers and other workers who have been in the US longer or employees who have legal status. Yet he dares not quit his job or even speak up for himself. The future prospects of his entire family now rest on his shoulders, and he feels he has no way out. His sole focus is earning money and bringing his daughters to the United States for their schooling.

Mr. Huang says there are too many people like him here, all waiting for immigration court decisions while searching for job opportunities and their uncertain dreams.

In a study on why Chinese immigrants have suicidal thoughts, all of the respondents reported experiencing common adaptive stressors and adverse life events before experiencing an episode of mental illness. One respondent said, "If I make a slight mistake, the chef will scold me, and sometimes I may only have 10 minutes to rest after working 12 hours. It's too exhausting, too much pressure."

Mobile Phones Are Their Companions

Due to the time difference, Mr. Huang can only video call his daughters in the early morning. Because he shares a small room with three other people, he can hardly make any noise during video calls. Each time he talks, he puts on headphones, turns on the camera, watches his family on the screen, and listens to his daughters' voices. Mr. Huang says his daily life is full of stress, confusion, and helplessness. He does not know how to solve his problems. These calls with his family have become the only joy in his life, his only spiritual solace.

Twenty-two-year-old Xiaoju is an undocumented immigrant with poor language skills and a very limited social circle making him extremely isolated. Holding his phone, watching short videos, and listening to music are his only entertainment besides work now. He says he doesn't have peers around him and basically has no environment to relax in. He feels many Chinese migrants become irritable due to the pressure of life. Because he doesn't want to be affected, he has been keeping to himself for a long time.

A Mobile phone is Xiaoju’s only companion, shot in Monterey Park

Courtesy Xiaoju

In addition to seeking peace in religion, Yuan Yang, too, uses his old phone to take photos, which offers him some joy in his solitary life. "My life may be ignoble now, but I am still trying to discover the beauty of it. That's my reason to keep going."

A UCLA study found that the biggest obstacles for Asian communities to access mental health resources is the lack of awareness of existing services. Many people are unsure how to seek assistance, while others fear the stigma around seeking mental health help. The limited number of Asian mental health professionals and therapists makes it even more challenging to find culturally attuned help.

According to a report from the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC), mental health clinics in Los Angeles County often have difficulty recruiting enough bilingual workers, leaving undocumented immigrants waiting for two to three months for an appointment.

According to Dr. Stephen Denq, undocumented immigrants from China are among the most vulnerable.

"Because they bear several times more mental burdens than ordinary people — language barriers, economic pressure, confusion about the future, emotional loneliness, all tied together with a person's mental health," Dr. Denq said.

But there’s no going back for the thousands who have sacrificed a great deal to come to the United States. "Once you shoot the arrow, there's no turning back,” writes Xiaoju on his social media.

This World Journal project is supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California,” a yearlong Ethnic Media Collaborative reporting venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.