Virginia social services' plentiful rules, lack of central authority ensure plenty of heartbreak

This story was produced as a project for the 2019 National Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Pittsylvania board member who raised questions ends up suspended by state

VIDEO: What is the Social Services Under Strain series?

Legislature funds ombudsman for foster children for first time

HEATHER ROUSSEAU | The Roanoke Times

The morning the child left, her foster mom picked up a cellphone and started recording. She told the girl to treat the video like a diary.

“I’m feeling sad right now because I don’t get to see you guys,” the 9-year-old says in the video. “You guys are my favorite people in the world. I wish I could just stay. ... I hope God can make us stay here.”

A social worker picked up the little girl from school later that day in February 2018. Her foster mother hasn’t seen her since.

She believes the removal was retribution for repeatedly asking her local social services agency to allow the child to see her siblings, a request she said the agency refused.

Virginia law and state social services policy require local departments to encourage sibling contact or communication, unless it’s not in the best interest of the child. The foster mom claims the agency knowingly violated this requirement.

That morning, after almost a year of living together as a family, the mom tried to explain to the girl what was happening. But she just kept asking why.

“She straight up told us, ‘This is worse than when I was taken from my parents because my parents would hurt us and you would never hurt me.’ ”

Because Virginia operates a decentralized social services system, employees at the local level are rarely held accountable for the life-changing decisions they make for Virginia’s families.

The Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission has detailed the Virginia Department of Social Services’ oversight problems for nearly 40 years. Efforts at the state level are underway to correct the issue, but progress is slow.

A yearlong investigation by The Roanoke Times shows failures at Virginia’s 120 local departments can go unaddressed for years because the state department does not exercise authority to enforce its own policies. As a result, Virginia families, foster parents, children and social services employees can be left with nowhere to turn when problems arise in their local departments.

The girl’s foster mom spoke to The Roanoke Times on the condition her name not be published. She said she fears her local social services agency, located in the state department’s northern region, would retaliate against her with legal action for sharing the story because she, like all foster parents, signed a confidentiality agreement. The girl’s identity is being protected because she is still a foster child.

Since her foster child was removed, the foster mom has appealed to legislators, the governor’s office, the state social services department, the county’s board of supervisors and the social services commissioner to convince the local agency to reverse its decision.

Former state Del. Chris Peace said he remembers meeting with the woman to hear her story. He said he wasn't able to learn from the agency's perspective what happened.

"Her case was active and complex," he said. "If I remember correctly, there were some local agency issues."

So far, no one has been able to convince the local department or its director to change course. The foster mom said it's too late. With each day, it becomes less likely she'll see the child again.

“They have no authority to force the local agencies to comply with state policies,” she said. “Then why do we even have state policies? If the local agencies don’t have to comply, then the policies are just meaningless.”

They started as foster parents by taking respite placements, where foster children stay for just a few days to give the parents a break or before they are placed in a more permanent home.

In March 2017, the couple received a call asking if they would be interested in a pre-adoptive placement, meaning parental rights had been terminated and the little girl soon would be up for adoption.

“We almost said no, because it sounded like maybe we couldn't handle it,” she said. “But we fell into a family routine really quickly.”

About three weeks after the child moved in, the local agency called again and asked if the family could take her brother for an emergency respite. He stayed for a couple of days and his sister was overjoyed to be with him again. The foster parents asked if he could stay with them permanently, but the agency said it wasn’t possible. He was removed and placed into a new foster home.

Later, they tried to plan a visit with him, but the foster mom said the agency told them the director ordered no further contact between any of the siblings.

The little girl constantly asked about them. She bought them presents and wrote them notes. At a doctor’s appointment, she asked, “Do you think my sister’s foster parents take her to the doctor when she gets sick?”

The agency rarely scheduled phone calls, which had to accommodate each foster parent's and the social worker’s schedule. In a team meeting, the foster mom said the girl’s therapists told the agency sibling contact would be beneficial. Eventually, the mom’s foster care licensing agency, a private group that trained and licensed her as a foster parent, told her to stop asking or the child would be removed, she said.

Virginia social services policy encourages local departments to create a plan that includes frequent visits or communication with siblings and to consider the wishes of the foster child in this plan. The policies say sibling contact should occur unless there are concerns that it would not be in the child’s best interest.

Peace, who works as a family law attorney in Mechanicsville, said there are cases when sibling contact is not advisable. He said children, often depending on their gender or age, process trauma differently. These differences can be seen within sibling groups and some children act out that trauma on their siblings.

"Every case is different, every family is different," Peace said. "The reason is often to do with the child's or the sibling's safety."

The foster mom said she saw how well the girl and her brother got along when he spent a few days at her house. Most importantly, she witnessed how not being able to see her siblings negatively affected the girl.

In February 2018, the foster parents received a notice about a foster care review hearing, which are held in local courts to evaluate the foster child’s plan for a permanent home and progress made in their case. The local agency told the foster mom not to attend, she said.

Virginia law and state social services policy say foster parents should be encouraged to attend these hearings and speak if the judge requests it.

Instead, the mom called the guardian ad litem, an attorney appointed to represent the child and make independent recommendations in their best interest. She left a message with the attorney’s assistant and asked her to bring up the sibling contact issue in court.

The foster mom said she never spoke to the guardian ad litem, but two days later she received a call from social services that her foster daughter would be placed in a new home.

Before a child is removed, Virginia social services policy requires agencies to hold a family partnership meeting attended by the foster parents and the child's social worker when a change in the child’s foster care placement is planned. The meeting is meant to explore all possible options to support the stability of the placement, according to the state’s foster care manual.

The foster mom said she did not attend a meeting before the child was moved to a new home.

Stability in foster care placements is a nationally recognized best practice. The Annie E. Casey Foundation, a philanthropic organization dedicated to child welfare research, consistently says that foster children who experience multiple placements have a much higher risk of developing behavioral problems and struggling in school.

A joint report from the foundation and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services says, “While there may be times when a new placement setting will be in the best interest of the child, it is generally important for states to continue to do as much as they can to keep placement setting counts to a minimum.”

“We both obviously were devastated,” the foster mom said. “And I went to therapy for a couple of months afterward trying to process what happened. That didn't help so I just kind of grieved my own way. But my husband won't even talk about it if I bring it up. He changes the subject. It really just broke his heart.”

Virginia is one of nine states that uses a state-supervised, locally administered social services system, which creates a division between the state and local offices.

The Virginia Department of Social Services operates a central office in downtown Richmond and five regional offices in Henrico County, Roanoke, Abingdon, Warrenton and Norfolk.

Each regional office employs a director and support staff in each program area to assist local departments with policy questions or to advise them on particularly difficult cases.

There are 120 local departments tasked with providing benefits and services to local citizens. Every locality is required to operate an office, but some create joint offices. For example, Roanoke County and the city of Salem operate one social services office to serve residents in both localities.

Each local office is led by a director, who reports to a local board of social services. Local board members are appointed by city councils and boards of supervisors.

The mix of state and local authority creates a confusing bureaucratic system that can be difficult for employees, families and foster parents to navigate. The state’s central office, the regional offices, the locality’s governing body and the local social services boards all have a level of authority over a local social services department. But unclear lines of authority leave no one directly holding local departments accountable. And in the end, local directors are free to make decisions autonomously.

State watchdog JLARC has analyzed the state’s social services system at least three times and each report has pointed out the state’s lack of authority. In a 1981 report, JLARC said the department had been trying to “operationalize” the system since 1977. The commission interviewed local directors for the report.

“Who is in charge?” one director said. “With the present administrative structure there seems to be no final authority to resolve critical issues. Localities exercise autonomy and the regions seem helpless to deal with their behavior. The losers are staff in all areas of the department and the client.”

A JLARC report in 2005 said the same — the lack of oversight meant the state department had limited knowledge of whether local departments were complying with federal and state requirements.

In 2018, a JLARC report on the foster care system said, “VDSS has historically narrowly interpreted its supervisory responsibilities, which are set in statute, and past VDSS leaders have equivocated about the state’s ability to assertively supervise foster care services and hold local departments of social services accountable.”

The Roanoke Times spoke with more than a dozen local directors or social services employees who confirmed the regional offices do not have the authority to enforce policies.

“We have been through multiple reviews and though they may not have the ability to ‘enforce’ policies, my department takes their recommendations very seriously and will implement any policies and procedures that are provided,” Carroll County social services director Teresa Isom said in an email.

Other directors agreed.

“They have the authority to come in and say, ‘this isn’t how I would do it’ and they can encourage you to do it this way, but the locality doesn’t have to follow,” Bedford County social services director Andrew Crawford said. “The only thing a regional office can do is go to the commissioner with a problem.”

According to Virginia law, the state commissioner can fire any staff member employed by a local department, including the director. The commissioner also can direct local boards to remove children from unsafe foster care placements and intervene when local departments fail to provide foster care services. But the 2018 JLARC report noted that state social services staff could not recall a single instance where these powers had been used.

Cletisha Lovelace, a spokesperson for the state social services department, confirmed in an email that as of February, those authorities have never been exercised.

JLARC reports have said regional offices are a critical component to oversight because they provide more day-to-day monitoring than is possible for staff in Richmond or the commissioner.

Regional offices conduct quarterly and annual reviews of program areas in each local department, but the state does not have a system for following up on recommendations to ensure they’ve been implemented.

In 1981, JLARC staff said the state social services department needed to resolve organizational confusion and strengthen the regional offices.

More than 35 years later, the state board issued the same recommendation. In an investigative report, the board said the regional offices have very few staff who are responsible for an unworkably large region. Proper oversight would require more manpower.

But over the years, the state has done the opposite. The number of positions at regional offices has fallen, which has contributed to the lack of oversight, according to JLARC reports.

Regional staff members were scattered across the state in 16 district offices or their own homes until 1970, when the state created seven regional offices to help expand oversight for the newly implemented food stamp and Medicaid programs.

In 1980, the state social services department had 240 staff located in seven regional offices. Those staff members supported about 5,500 staff in local departments, at a ratio of one regional staff member for every 23 local workers. In 2005, 96 regional positions supported approximately 8,500 local staff, or one regional staff member for every 88 local workers, according to JLARC reports.

Today, 57 regional positions support about 11,000 local staff, or one regional staff member for every 193 workers.

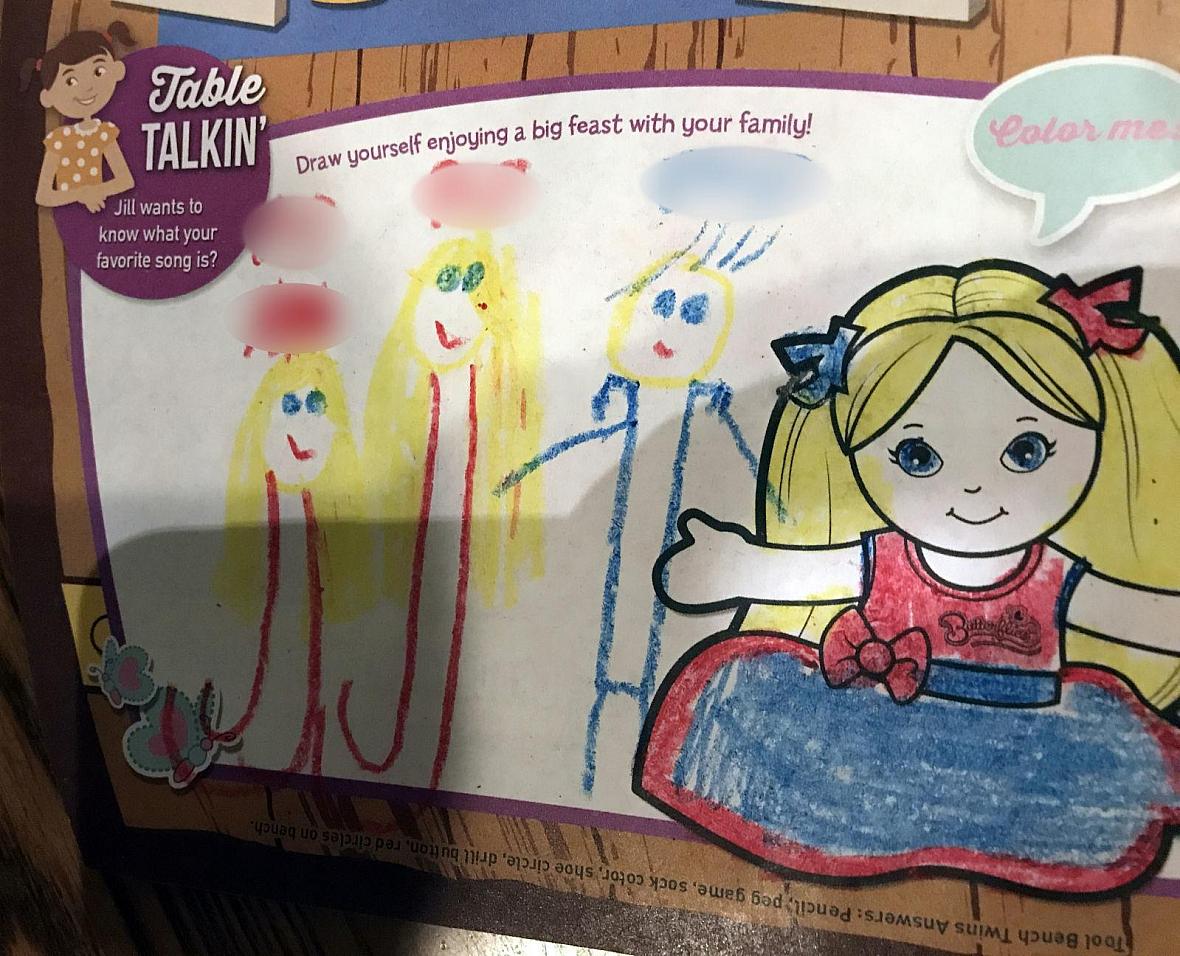

The Cracker Barrel children's menu said, “Draw yourself enjoying a big feast with your family!”

The 9-year-old girl drew herself with long blonde hair, red legs and blue eyes. She drew her mom the same, just a little taller. Her dad sported spiky blue hair and broad blue shoulders.

She picked up her red crayon and wrote her initials above the drawing of herself. But then, she scribbled it out. She wrote the first letter of her first name again, but this time, a new last initial — one that matched her foster parents sitting at the table.

The little girl had been in foster care for more than six months.

When she first arrived at her new home, she had constant meltdowns. They were over small things, like what her foster mom was cooking for dinner. She would fall on the floor and refuse to move or speak. She struggled to socialize or show emotion.

But soon, she got better. Her grades improved, her tantrums were fewer.

When the day came for her to leave, her foster mom struggled to explain. She told her it wasn’t always up to them what happens, that if they could have her stay, they would, that they were going to try to get her back, but it wasn’t their decision.

Now, the foster mom said she’s not sure her family will ever be able to take in another child.

“They're basically just asking foster parents in general to take on this huge emotional investment and we have no way of protecting ourselves,” she said. “We were pretty much told to shut up and get in line. There was no support or advocacy.”

The mom has since become active in suggesting legislation that could help fix the problem. She supports Montgomery County Democratic Del. Chris Hurst’s children’s ombudsman bill, which would create an independent office to investigate citizen complaints about the state and local social services departments. A similar bill was introduced by Sen. John Edwards, D-Roanoke, and passed the full House and Senate in 2008, but it was never implemented.

When Hurst reintroduced the bill last year, the House Appropriations subcommittee on Health and Human Resources voted 5-3 to pass it by for that session. He has introduced it again this year and the bill has passed the House of Delegates and the state Senate.

Last year, Sen. Bryce Reeves, R-Spotsylvania, introduced a foster care omnibus bill that implemented many of the recommendations from the 2018 JLARC report, including establishing a foster care caseload standard and creating a foster care health and safety director position.

The bill also enshrined into law an emergency regulation previously passed by the state board. The regulation allows the commissioner to take over a local department if it fails or refuses to provide foster care services or takes any action that poses a substantial risk to the well-being of a child.

But the regulation does not define when that step would be taken by the state. The commissioner said at a state board meeting in August he intends to keep the language vague because the department has never implemented something like this. The regulation would then become more specific in the procedure and could later be updated after the department learns more about how it will work.

But directors say leaving it up to interpretation could mean vastly different things when a new commissioner eventually takes the job.

JLARC reports for close to 40 years have said the state needs to define its policies and rules so they can be better enforced. “A complete failure to provide services is less likely than a failure to provide certain services or a failure to provide services to some children,” the 2018 report read.

For the Richmond-area foster mom, her case was a failure. She and her husband loved the little girl, helped her heal, helped her grow, until they lost her to another foster placement. The child lost her parents, then her siblings and the foster parents she grew to love.

“I could talk all day about how wrong it was, what they did to us, but that just pales in comparison to what they put her through,” she said. “For her, that was her entire life.”

[This article was originally published in The Roanoke Times.]