What it's like to be in a youth mental health treatment facility: one woman shares her experience

The story was originally published by WUNC with support from our 2023 Data Fellowship.

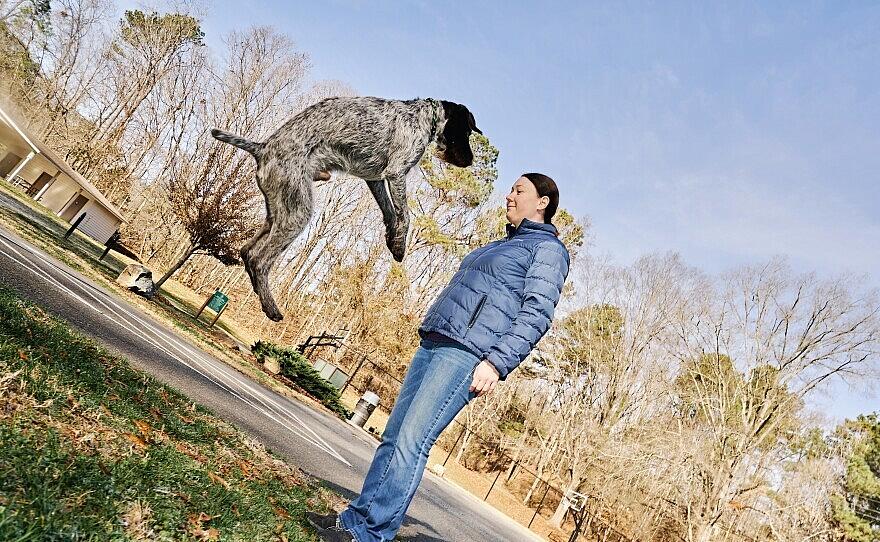

Ariel Wolf during an interview with WUNC in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Matt Ramey/For WUNC

This is the second in a three-part series investigating North Carolina's psychiatric residential treatment facilities where children with complex behavioral needs are sent for care. Read Part 1 and Part 3 here.

Ariel Wolf unpacks Newt, her German Wirehaired Pointer, from the back of her car. She trains dogs for competitions and has trained Newt as her service dog. Wolf is diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a connective tissue disorder that affects her skin and joints.

"All the little things that he does, being able to, you know, help me up stairs, being able to help with my balance, picking things up for me," said Wolfe, 30, on a brisk December morning at Chapel Hill's Umstead Park. "It helps me have more energy and less pain and I'm able to do more of the things that I want to do because he helps me with the things that I need to do."

Wolf leads what many people would consider a normal life. While that might seem unremarkable, it actually makes her an anomaly. As a teenager, Wolf spent time in Psychiatric Residential Treatment Facilities, more commonly known by their acronym PRTF. That's in addition to the 30 acute care hospital stays she had for various mental health crises.

"So in total, I've spent three-ish years of my life, mostly between the ages of 15 and 18, institutionalized," she said.

Ariel Wolf Trains her dog Newt in Chapel Hill, N.C.

Matt Ramey / For WUNC

Advocates say many people who endure what she did as a teenager are more likely to end up homeless, in prison, or dead.

Wolf has bipolar disorder. She said she could have been diagnosed as early as age 6, though that wasn't really a consideration in the 1990s. She began to self-harm and was first hospitalized in eighth grade.

Her mother, Marcia Roth, who herself works with children with special needs, said the family tried to find help for her daughter, but faced a health care system not set up to do that.

"So here I'm working with kids with special health care needs, and my own daughter is treated with such, oftentimes, disdain," she said.

In elementary school, Wolf was put on medications that she said were not right for her. Later, Roth remembers doctors calling her daughter a "problem child" when they took her to a psychiatric hospital. Eventually, she ended up at a PRTF.

"My daughter experienced no trauma of any real magnitude, except at the hands of treatment facilities that we went to, with the express desire for her to receive therapeutic treatment and to be healed," Roth said.

Ariel Wolf poses for a portrait in Chapel Hill, N.C

Matt Ramey/For WUNC

Providers say they offer trauma-informed care

Wolf and advocates say this is one reality many children experience, yet it's far from what PRTFs themselves portray. In one promotional video, a narrator says a struggling child can overcome challenges with "trauma-informed care from those prepared to do the heavy lifting."

Yet, it's exactly that type of care that families and advocates say is missing from these facilities.

Until recently Joonu Coste worked as an attorney for Disability Rights North Carolina, the state's official protection and advocacy system. Coste is now an assistant attorney general. She described children as being warehoused in PRTFs instead of given the kind of care they need to heal.

"Supervised by individuals with little to no mental health training," she said. "Typically, these are people who are hired as staff with GEDs, high school diplomas and are given the minimal training that is required under state licensing law."

Those who run PRTFs disagree. Dr. Van Catterall, the chief clinical officer at Alexander Youth Network, a mental and behavioral health network in Greensboro that includes PRTFs, said they do provide good care.

"The keystone of our approach in working with kids is being trauma-informed," he said, "and understanding where behaviors come from, in terms of their background."

Ariel Wolf trains her dog Newt in Chapel Hill, N.C

Matt Ramey

Advocates say another issue is turnover. It's notoriously high in these facilities. Wolf, who today manages her bipolar symptoms with a combination of medication and therapy, said that's not especially surprising given the conditions some workers endure.

"You're going to have to hold people down, you're going to be spit on. You're going to have people throwing bodily fluids on you. Your life may be in danger," she said.

Behavior as a result of trauma

Providers like Catterall recognize where these behaviors come from.

"What often lies behind that (behavior) is trauma in the young people's background," he said. "A lot of our kids have either been victims, unfortunately, of abuse or neglect. Some of them have witnessed domestic violence in their homes, so aggressive behavior has been modeled for them."

Although state officials and behavioral health providers that WUNC spoke with say they want to provide more trauma-informed care, advocates like Coste argue that's not what happens. Instead, she says the care provided only adds to that trauma.

"We have staff at group homes telling us that they spend so much time trying to work through the trauma that the child has experienced while at the PRTF before they can even get to an underlying issue that caused the child to have the crisis in the first place," she said.

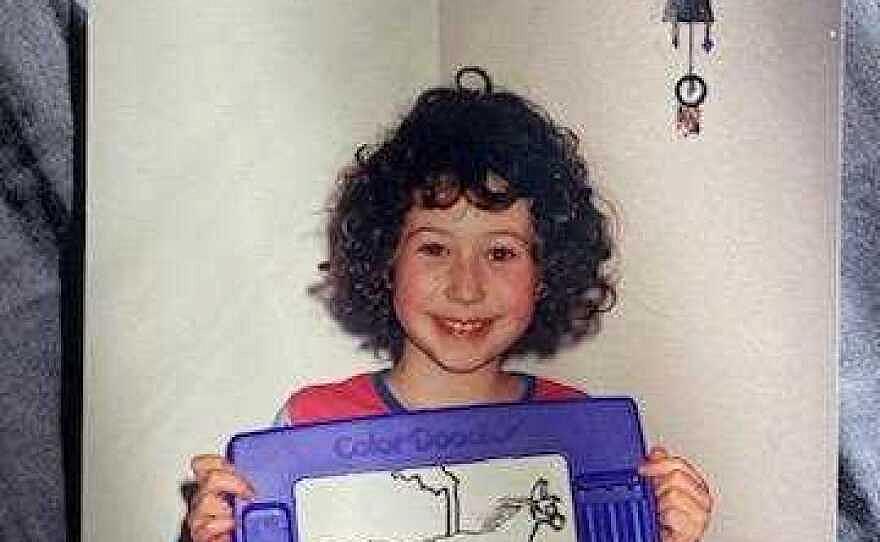

Ariel Wolf as a child

Courtesy of Ariel Wolf

But moving away from a system that uses these kinds of facilities seems unlikely. Advocates want to see more community-based care. State health leaders say they agree, but that takes an even larger, well-trained workforce. Catterall said these residential options remain a necessary part of the care continuum.

"When youngsters get admitted to the kind of facility that we're talking about, it's happened after a long chain of events where, unfortunately, that community-based care … was not able to successfully stabilize them," he said.

In reflecting on her time at PRTFs, Wolf said it accomplished one very basic goal.

"I am alive today because my parents loved me enough to keep me warehoused for several years on end in PRTFs," she said. "They didn't help me. I have a lot of trauma as a result of it, but I'm alive, and I love my life."

Advocates say if all these PRTFs do is keep people alive, that's not good enough to continue sending them millions every year in Medicaid dollars.