When Louisiana reformed state mental health care, it left many with nowhere to go

The story was originally published by The Current LA with support from our 2024 National Fellowship.

A building sits empty and overgrown with weeds on the historic campus of the Central Louisiana State Hospital in Pineville, La., on Thursday, Dec. 5, 2024.

Photo by Alena Maschke

There’s a stream that cuts across the grounds of Central Louisiana State Hospital, traversing its rolling hills dotted with age-old oak trees. To the right of its entrance, bleachers and the fence of a baseball diamond, where patients and staff once played on the same team, sit crawling with vines.

Today, there are no patients to be found on Central’s historic Pineville grounds. The hospital, which once housed and treated over 3,000 patients, has been moved to a new, much smaller campus on the outskirts of town, serving a daily average of just 114 patients.

“You have to admit: this is one scenic place,” said local historic preservation consultant Paul Smith, who has been part of a team digging into the history of the former site of the last remaining state hospital serving a fully “civil” — meaning non-criminal — population.

Central’s historic campus is a relic of a bygone era. In the late aughts, Louisiana shuttered most of its state-run mental institutions. The patchwork system that emerged leaves glaring gaps, experts say, exacerbating problems with crime and homelessness.

Like much of the nation, Louisiana is dealing with a mental health crisis, deepened by the coronavirus pandemic. In February 2021, nearly half of Louisiana residents reported symptoms of anxiety or depression, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). Louisianans are also more likely to die by suicide or drug overdose.

Meanwhile, young people in need of inpatient mental health care are shipped hours away from home to receive care. Patients with chronic mental health conditions, who may stand to benefit from long-term inpatient treatment, instead find themselves caught up in cycles of emergency department visits, homelessness and incarceration. Those deemed incompetent to stand trial languish in jail for months awaiting placement in the state’s only forensic psych hospital.

Curtains hang inside the window of a mechanic shop on the historic campus of the Central Louisiana State Hospital in Pineville, La., on Thursday, Dec. 5, 2024.

Photo by Alena Maschke

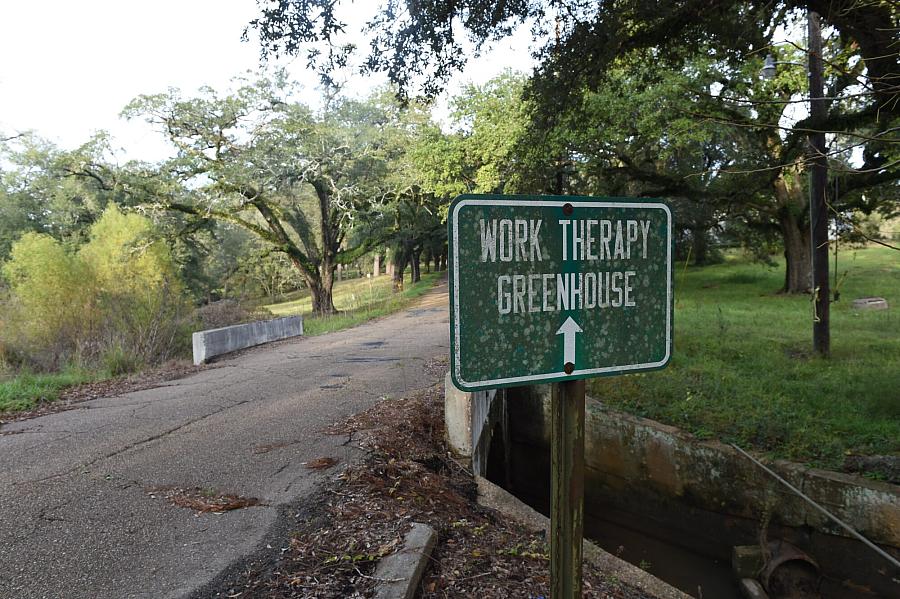

A sign points the way to a former work therapy greenhouse on the historic campus of the Central Louisiana State Hospital in Pineville, La., on Thursday, Dec. 5, 2024.

Photo by Alena Maschke

The state has increasingly taken a backseat in providing inpatient mental health care, relying instead on outpatient services and private acute-care hospitals to fix Louisiana’s mental health struggles.

During the administration of Gov. Kathleen Babineaux Blanco in the early 2000s, the Legislature and political leadership began re-evaluating the delivery of mental health care in Louisiana, and the state’s role in it, especially with respect to state-funded and staffed psych hospitals like Central.

Like many states, Louisiana once had a network of state-run mental health hospitals serving patients of all ages, regardless of their ability to pay for that care.

Concerned about the cost of the state’s hospital system, Blanco ordered a study of state spending on it and an alternative community-based system of delivering care, an approach aligned with a nationwide movement away from state “asylums” that began under President John F. Kennedy and continued throughout the second half of the 20th century. Analysts projected the move would save the state money.

Blanco’s successor, Gov. Bobby Jindal, facing significant budget woes, executed on that theory by shutting down and selling several hospitals, shuffling patients into an-ever decreasing pool of beds in only two remaining state hospitals, one of which was the historic Central Louisiana State Hospital campus.

But cost-cutting wasn’t the primary objective of those closures, Alan Levine, Jindal’s health secretary at the time of the closures, argues.

Instead, he said, the closures came with investments in outpatient care, like a $90 million investment into New Orleans’ human services district, that reflected an attempt at “restructuring the system”.

“The state institutions perhaps could have worked if they were properly capitalized over time, but they weren’t,” Levine said.

Instead, they were considered a “relic,” according to Levine, and a more modern approach would be required to solve the state’s mental health crisis, which was especially apparent in New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

“There might have been a time where institutionalizing people was the only option, but we’ve learned enough to know that it’s not necessarily the right option, and in some cases, it’s a violation of people’s rights,” Levine described the philosophy behind his approach.

A greenhouse that was once used for occupational therapy sits in disrepair on the historic campus of the Central Louisiana State Hospital in Pineville, La., on Thursday, Dec. 5, 2024.

Photo by Alena Maschke

The dairy barn stands unused on a hill overlooking Buhlow Lake, a former pasture, on the historic campus of the Central Louisiana State Hospital in Pineville, La., on Thursday, Dec. 5, 2024.

The goal, according to Levine, was to strengthen community support systems, such as human services districts, to prevent patients from getting to a stage where they needed hospitalization.

Meanwhile, most formerly state run facilities were privatized. But conditions for patients — one of the concerns that was at the core of the deinstitutionalization movement — didn’t necessarily improve.

One example is Northlake Behavioral Health System in Mandeville, housed at a facility formerly run by the state as Southeast Louisiana Hospital. The state-run facility was closed under Jindal in 2012 and subsequently privatized, and has faced challenges over the quality of care provided there ever since.

Despite concerns over patient safety that drew three federal citations, the state has been reluctant to take action.

Northlake provides “safety-net beds” for the state, as one of three hospitals that the Louisiana Department of Health contracts with, and is the largest provider of those beds.

When preventative outpatient services fail, “safety-net beds” have been the state’s last resort to make up for the decline in state-run inpatient beds. According to Office of Behavioral Health Assistant Secretary Karen Stubbs, they constitute “an alternative place to get those services.”

And Louisiana is in no position to downsize its offerings for patients in need of mental health care. It is currently under a consent decree following a suit by the U.S. Department of Justice alleging that the state was improperly warehousing people in nursing homes who really needed mental health care instead.

Louisiana is also fighting a lawsuit by the Southern Poverty Law Center that alleges that the state is falling short on its responsibility to provide young people with access to mental health care, especially care that allows them to remain in their communities instead of being shipped off to institutions far away from their homes.

A crisis response system for youth was rolled out earlier this year, with two providers offering services so far, covering the Acadiana and southwest Louisiana regions.

On the adult side, things have been difficult. LDH has struggled to get the crisis response system, the development of which was mandated as part of the consent decree, off the ground.

“Louisiana was one of the few states that did not have any kind of comprehensive crisis response, and so they’ve tried to implement something, but the way they’ve done it has just been not effective,” said Holly Howat, executive director of Beacon Community Connections, a Lafayette-based nonprofit with programs addressing social determinants of health, substance use disorders and recidivism in southwest Louisiana.

Howat, who has closely followed the unsuccessful attempts to set up a crisis response program for adults in Acadiana, said a lack of funding has been a major obstacle. “We want you to do this, you can bill Medicaid, but we’re not putting in a bunch of money for it,” said Howat of the state’s approach. “It’s kind of an unfunded mandate.”

Medical equipment is lined up along the ambulance bay of one of the last buildings to still have been used on the historic campus of the Central Louisiana State Hospital in Pineville, La., on Thursday, Dec. 5, 2024.

Photo by Alena Maschke

A sign advises drivers of the location of the historic campus of the Central Louisiana State Hospital in Pineville, La., on Thursday, Dec. 5, 2024.

According to Stubbs, grant funding has been allocated to help prospective crisis providers, but funding data has not been made public by LDH and the department did not provide information on the funding allocated in response to several requests by The Current/The Acadiana Advocate.

Stubbs pointed to Medicaid and its expansion as a shift in how the state expanded access to mental health care for low-income residents. But experts say low reimbursement rates limit patients’ choice of providers, and coverage for inpatient treatment — although not technically capped at a specific length of stay — typically doesn’t extend past acute care.

“If you are in poverty, even if you’re on Medicaid, it’s hard to navigate, to figure out who will see you, who will actually provide services to you,” Howat said.

Still, Medicaid expansion and the program’s increased coverage of mental health care are glimmers of hope, Howat said. “That is something that I think the state is doing right,” Howat said. “Reimbursement rates need to be adequate for what it costs to actually deliver services these days, but the fact that they’re even covered is positive.”

Without a comprehensive crisis response system, local health and human services districts, also referred to as local governing entities or LGEs, currently serve as the primary state-funded system of community-based services.

LGEs took hold statewide just before the closure of state hospitals. At the time, the districts and their offices weren’t necessarily designed as a replacement for the disappearing state beds, but rather constituted a local takeover of infrastructure and services that were already being provided by LDH at those same locations.

“We know our community better than you,” is how Brad Farmer, executive director of the Acadiana Area Human Services District, describes the philosophy behind the change from state to local control. “We think we can provide better services that are more responsive, more appropriate, more meaningful to our population.”

A Louisiana Department of Health truck is parked outside a workshop on the historic campus of the Central Louisiana State Hospital in Pineville, La., on Thursday, Dec. 5, 2024.

Photo by Alena Maschke

Since then, districts like AAHSD have vastly expanded their services. The district now offers same day mental health assessments, counseling, inpatient referrals, medication management and more, serving 15,000 people at its clinics per year.

It has done so with limited support from the state. While the district’s entire budget, with the exception of certain grants, comes from the state, that budget hasn’t increased since its inception nearly two decades ago, putting the district at a significant loss when adjusting for inflation.

“If we’re in a budget crunch in the state, there’s really only going to be two things that are possible to decrease: higher education and healthcare,” Farmer said of his decade-plus experience with Louisiana budget politics.

Farmer said he’s been lucky not to have been forced to fire staff or close locations due to a lack of funding, although his staff has shrunk over the past decade. “We have been very fortunate. We’ve not had to lay anybody off,” Farmer said. “We’ve addressed these things through attrition.”

LGEs like AAHSD do not provide inpatient services, a responsibility that now falls almost entirely to private hospitals like Northlake, with the exception of the few remaining beds provided directly by the state at its two remaining hospitals.

And while most patients may be served appropriately through acute care hospitals and outpatient services, some patients require more long-term care, said Richard Kramer, former director of two state hospitals closed under the Jindal administration. For those patients, he noted, there are virtually no resources available today.

“People shouldn’t just be locked in hospitals like they used to be in the old days for the rest of their life,” Kramer said. “But we went all the way from one extreme to the other,” he added. “There’s not really any support for people beyond acute hospitalization.”

A building sits empty and overgrown with weeds on the historic campus of the Central Louisiana State Hospital in Pineville, La., on Thursday, Dec. 5, 2024.

Photo by Alena Maschke

Attitudes toward those struggling with mental illness have shifted significantly in the century that has passed since Central Hospital was built, though some of its therapeutic resources, like a greenhouse for patients to garden in, would likely find resonance today. With the historic hospital shuttered for good and its campus being sold off in pieces, those resources have been lost to the public, without a clear path for replacement.

Driving across the vast campus, Smith, the preservation consultant, summarized attitudes at the time, as they were relayed to him by a former hospital administrator. “The idea was to isolate people from the community,” Smith said. “Ok fine, let’s build a world for them. That’s what this is.”

That world is now a thing of the past. Developers are eying parts of the decaying Central Hospital for conversion into a private senior care facility.

“Hopefully, few people need to be institutionalized,” Howat said. But, “we have to have some place for people to be,” she added. “If you don’t offer that, you’re going to have them homeless or in jail.”