Will Pharmacist Resistance Hamper Law to Expand Access to HIV Prevention Meds?

This article was produced as a larger project by Larry Buhl for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2019 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in his series :

New Law Aims to Expand Access to HIV Prevention — But Will It?

Pharmacies Grapple With Red Tape as States Try to Allow Pharmacists to Prescribe PrEP

In 2012, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Truvada to prevent HIV in a regimen called pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, a potential life-saving game changer for people at risk of contracting the virus. Truvada, taken along with other meds, can also be used in post-exposure prophylaxis, or PEP, for people who may have accidentally exposed themselves to the virus. Studies have shown that PrEP, which now can be prescribed with a newer drug, Descovy, can reduce the risk of contracting HIV from sex by up to 99%, and the federal government considers widespread use of PrEP and PEP as a key part of its goal to significantly reduce the number of HIV infections. But a fraction of the number of people who could benefit from PrEP are taking it, partly, HIV advocates say, because there are so many obstacles to obtaining the medication.

The California Department of Public Health estimates that up to 238,628 Californians would meet the criteria for PrEP – that is, they have unprotected sex or are IV drug users. But waiting several days for a doctor’s visit, another few days for HIV test results and maybe another day for insurance preauthorization can make PEP unusable and can make potential users of PrEP think twice about whether they really want the meds.

To help boost the sale and use of PrEP and PEP, the California Legislature last year passed SB 159, a first-in-the-nation law allowing pharmacists to write prescriptions for it (and for PEP) and, in theory, to let the patient get the medication on the same day. The hope is that the law will significantly increase PrEP/PEP use for populations most vulnerable to HIV: Latino and Black gay and bisexual men whose doctors are less likely to prescribe the medication. But a question remains whether this well-meaning law could ultimately be hampered by systemic issues of a for-profit health care system, a system where disparities of care can be intractable.

In the first part of this series, I explored the disparities in PrEP access throughout California, and which regions might benefit from the law. Sprawling San Bernardino County, with its lack of LGBT support services and few public clinics, I speculated, could benefit the most – while San Francisco, the least.

In part two, I dig deeper into whether the dispersion of retail pharmacies and financial disincentives for pharmacists might undermine the law.

The Theory: SB 159 makes it easier to get PrEP

Before SB 159’s passage, obtaining PrEP required a prescription from a doctor and an HIV test. (If you test positive you don’t need, and can’t get, a prescription for PrEP, though people with HIV can get Truvada or Descovy for treatment.) The law still requires an HIV test, and standard protocol for PrEP still includes ongoing kidney function tests, to be conducted every three months. Each of those steps creates a potential delay for people who want to get the medication. There’s a financial hurdle, too: Lab tests are often an out-of-pocket expense.

SB 159 eliminated insurance preauthorizations for PrEP and PEP, saving, at the very least, time. Another part of the law, allowing pharmacists to prescribe PrEP and PEP, was designed as an end run around doctors, by partially “de-medicalizing” these potentially lifesaving meds. This part is meant to equalize very unequal health care outcomes because providers in some areas are much less likely to prescribe medication to prevent a disease that is largely spread through sexual activity and IV drug use – if they even know about the medication.

Many young, sexually active LGBT participants in Los Angeles told me their primary care doctors were hostile to the idea of providing medication to prevent HIV from sex. One said his doctor asked why the medication was needed and, “Why are you gay?” Several participants agreed that many primary care physicians, especially in Latino communities, are from other countries, older and conservative, and that many doctors who serve Medi-Cal patients are generally not gay-friendly. Some doctors and nurses are also clueless about HIV and STD testing, especially if their practice gets few requests for them. “If they do an HIV test, they don’t do a full STD panel, and never a throat swab or anal swab, and they don’t know what billing code to use,” said one participant.

Dr. Clint Hopkins, owner and pharmacist at Pucci’s Pharmacy in Sacramento, testified before the legislature in favor of SB 159, because, as he told Capital & Main, “Pharmacists are the most accessible health care providers in the community.”

Hopkins claims that one HMO, Kaiser Permanente, makes it difficult to get PrEP, requiring referrals to an infectious disease doctor in the network who will order the HIV test. “It can take up to two months to get PrEP [through Kaiser],” Hopkins said. When asked to verify that the process could take up to two months, a Kaiser spokesperson declined to comment.

SB 159 set out to prevent resistance from physicians, insurers and HMOs. Obstacles from the health care industry would also, in theory, be reduced by simply obtaining both a prescription and meds from pharmacists. But there are three ways the law may fall far short of its goal, at least initially, of making PrEP access easier for the most vulnerable populations. Unless retail pharmacies, a., opt in to the law, b., provide the required HIV test on-site and c., make that HIV test free, customers who are younger, lower income, or in areas with few pharmacy options won’t find it easier to get PrEP.

But Hopkins is concerned that the resulting law doesn’t go far enough. “Nothing in the law says insurers have to pay for the meds or the lab tests. Patients may have an undue burden to pay for testing out of pocket. And there is a lack of testing sites even in Sacramento. If we want to end HIV then people should be able to walk into any pharmacy and get a test for free.”

PrEP deserts might remain deserts

As reported in part one of this series, most urban areas in California have an extensive network of PrEP providers, some of which offer one-stop shopping for PrEP. Large swaths of the state have fewer physicians who have written or are willing to write a prescription, according to CDC data. Any doctor could prescribe PrEP or PEP, but not all know what the medication does, and more conservative doctors stigmatize and “slut-shame” patients who ask for it. Doing an end run around doctors, thus streamlining the process of getting PrEP/PEP, is one goal of SB 159. But the effectiveness of the law depends in part on where the pharmacies are and whether they choose to participate.

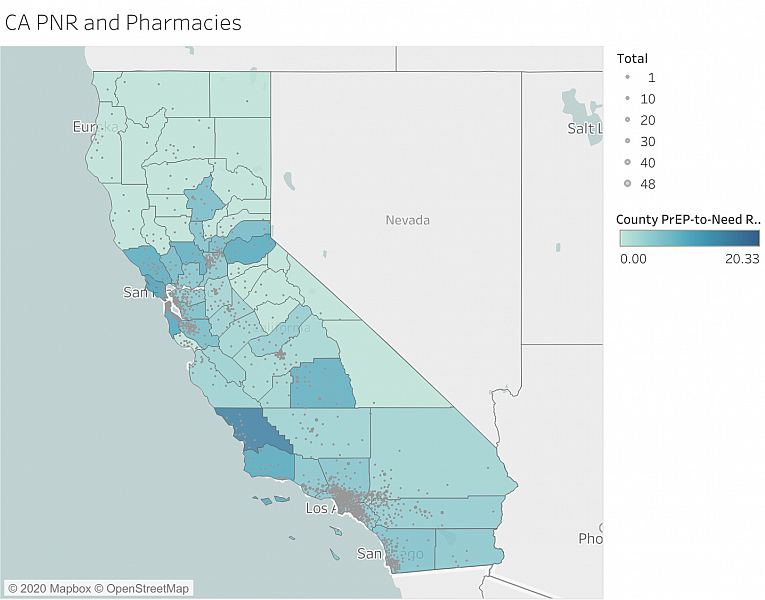

I have identified San Bernardino County as one of the counties that could be helped most by SB 159. It has one of the lowest overall rates of PrEP use – 35 out of 100,000 people – and among the lowest rates of use of PrEP based on the estimated number of people who could benefit from it (PrEP-to-need ratio, or PnR), and the lowest PnR in California for people under 24 years old. There are currently only eight locations where prescriptions are being written for PrEP, for a population of 2 million – making much of the county a PrEP desert. (A 2019 study classified PrEP deserts in the United States as areas where the one way driving time was 30 minutes or more.) SB 159 could help shrink some of those deserts, provided that pharmacies in those areas agree to participate in the law.

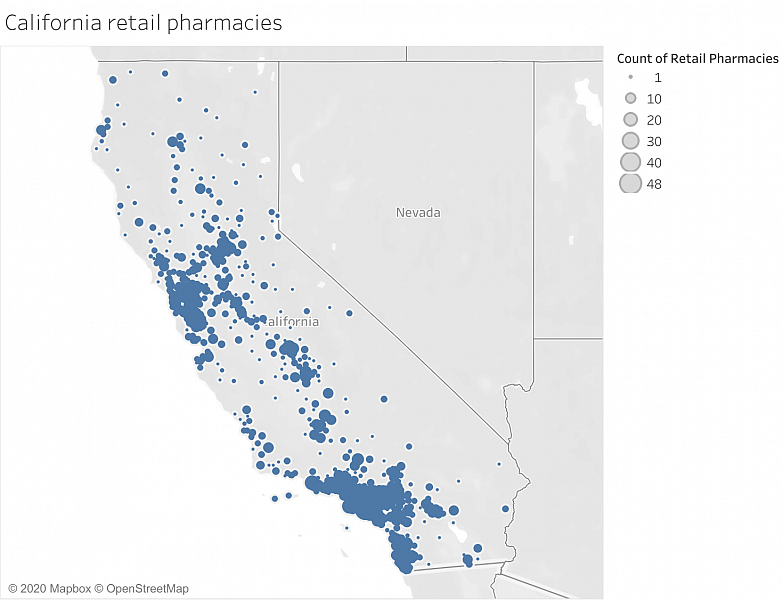

However, overlaying a map of California pharmacies on a county map of PnR shows that even if the majority of pharmacies participate in SB 159 – again, not a sure thing – there will still be PrEP deserts in California. Hayfork, in Northern California, is in a PrEP desert. The options for its residents for getting a PrEP prescription are Planned Parenthood in Redding and Redwoods Health Center in Redway, 43 and 45 miles away respectively. But even with SB 159, Hayfork would still be a desert: The nearest pharmacy is a CVS in Weaverville, 29 miles away and about 40 minutes of driving time.

Even under SB 159 the process for obtaining PrEP and PEP is a little more complicated than procuring birth control, which is covered by another opt-in law. SB 159 spells out requirements for HIV testing before a pharmacist can furnish PrEP, stating that a patient must be “HIV negative, as documented by a negative HIV test result obtained within the previous seven days from an HIV antigen/antibody test or antibody-only test or from a rapid, point-of-care fingerstick blood test approved by the federal Food and Drug Administration.”

In theory, a patient could get a test at a free clinic, if there’s one nearby, a day or so before heading to the pharmacy for a prescription. But when I contacted a CVS Minute Clinic in West Hollywood, which has been providing PrEP under an arrangement to work with one or more physicians called a collective practice agreement (CPA), I discovered several obstacles:

- A nurse practitioner first performs an evaluation by appointment only (there are no walk-ins due to the COVID-19 crisis).

- The NP then sends the patient to a lab for an HIV test.

- After a wait that can last 72 hours, patients receive the results and may return to the Minute Clinic for the medication.

Additionally, patients must call their health insurance company to see if labs are covered, and these insurers might not be open on the weekends. This practice would make getting PEP, which must be taken within 72 hours of risky sexual contact, futile, and could make those who want PrEP give up. And this is at a pharmacy/clinic in a city known for decades as a mecca for LGBT people.

As mandated by the Affordable Care Act, HIV testing is free for those with insurance, but it may not always be easy to find a place offering HIV tests. According to CDC data, there are 20 places to get an HIV test, free or not, within three miles of ZIP code 90069, West Hollywood. But a search of Hayfork (in the middle of a PrEP desert) turns up no testing locations nearby. ZIP code 92363, Needles, shows one testing location seven miles away. Needles, in San Bernardino County, abutting the Arizona border, has only one pharmacy, a Rite Aid. If this pharmacy doesn’t offer HIV testing, residents there wanting PrEP will have to make a significant trek to get one. If the store doesn’t participate in SB 159, it will be a moot point, and residents wanting PrEP will have to travel at least 22 miles to get an HIV test and prescription. Then they’ll have to take that prescription back to their pharmacy.

A lack of incentives for pharmacists

One nagging concern about the rollout of SB 159 is that pharmacies will not opt in, either because of financial or moral objections. In those cases, the current PrEP deserts in California will remain deserts. In other words, for the law to work, pharmacists must buy in. To ensure that buy-in, it helps to have a financial incentive beyond the small Medi-Cal payment for each prescription.

The key for successful implementation of SB 159 is widespread pharmacy buy-in, according to Maria Lopez of Mission Wellness Pharmacy in San Francisco. “If they’re paid adequately they might [buy in], she says. “They have to invest in infrastructure and training staff, and that costs money.” Lopez is also developing a training module to instruct pharmacists on the law.

Hopkins hopes that more pharmacies like his will offer free, on-the-spot HIV testing to help reduce the number of steps people need to take to obtain PrEP. “There is no way to do [free testing] without the pharmacists losing money. If patients don’t pay for it, who will? Also, there is time involved. There’s OSHA, training requirements for the staff.”

A precursor to SB 159 was a 2013 law expanding the ability of pharmacists to act more like doctors, to order lab tests and interpret and modify prescriptions. But Hopkins, who did register for the 2013 law, SB 493, says that as with testing services, the lack of financial reimbursement from the state has prevented most pharmacists from registering.

"We’re not trying to get rich,” Hopkins said. “But the equipment and supplies are not free. We are paid pennies on prescriptions. Many opted not to get registered on SB 493 because it will cost them money.” And if they don’t get registered on SB 493, they won’t be able to offer testing, meaning more time and money will be spent by a potential PrEP customer before the medication is sold.

Hopkins and Lopez, whose practices for years have had certified physician assistants with doctors who prescribe PrEP and PEP, say CPAs can help pharmacists to provide these meds more easily. But Hopkins believes only a small percentage of pharmacies will do this because there’s no financial incentive. “Insurance providers typically will not recognize a pharmacist for the services that they provide outside of dispensing prescriptions. If there were a financial incentive, I’m certain that many more pharmacies across the state, both independent and chain alike, would seek out these relationships and provide more services.”

If few pharmacists, or, more important, pharmacies and their parent companies, decide to participate in SB 159, the current PrEP deserts in California will remain deserts.

Outreach and education needed, but who will provide?

Just as some doctors are unaware that Truvada and Descovy can be used to prevent HIV, it’s news to many pharmacists as well. A 2018 study showed that nearly three quarters of pharmacists nationwide didn’t know the CDC protocols for PrEP, and nearly half didn’t even know what PrEP is.

In California, there may be greater knowledge of PrEP, but very little awareness of SB 159, and without any money in the state budget for education and outreach in the California FY 2021 budget, that outreach is up to the California Pharmacists Association and LGBT social services organizations.

I randomly called seven San Bernardino County pharmacies in mid-June, nearly six months after the law went into effect, to see, first, whether they already provided PrEP with a doctor’s prescription, and whether their pharmacists were going to take the training to prescribe it themselves. For those pharmacies that sold PrEP with a doctor’s prescription, not only was pharmacist training not in the cards, none of them had heard about SB 159. An assistant at the CVS Minute Clinic in Rancho Cucamonga said that he wasn’t sure whether the pharmacy carried Truvada or Descovy, but that I should make an appointment on the website to meet with a nurse practitioner to learn more. But on the website, neither PrEP nor PEP nor anything related to HIV was given as an option.

The Planned Parenthood of Victorville was very helpful, though they don’t have meds on site: If I wanted PrEP they would set up an in-person visit to give an HIV rapid response test with same-day results. Planned Parenthood would submit a prescription for Truvada at the pharmacy of my choice. Calling on a Friday afternoon I found available appointments for Monday, but not over the weekend.

This brings up another potential benefit of SB 159. Many pharmacies are open on weekends and after 6 p.m.; most doctors’ offices and clinics are not. That might be a boon to people who need PEP, which has to be taken within 72 hours after sexual activity – right now an ER, if it carries it, is the only option for obtaining PEP on a Sunday afternoon. Again, the law only works as intended if pharmacies opt in.

The California Board of Pharmacists said that a 90-minute training module is close to being complete and that pharmacists must complete that or other state-approved training in order to prescribe PrEP or PEP. But as of mid-July no pharmacists had completed any training, and there was a statewide campaign to inform Californians about SB 159. I contacted two of the largest chains in the U.S., Walgreens and CVS, to see whether they would launch awareness campaigns. CVS responded by reiterating its support for HIV-related meds but said nothing about SB-159 awareness in California. A Walgreens spokesperson, in an email, said the chain was “considering a pilot program in the state to gather key learnings and insights that will help to determine any future steps in how our pharmacists can more broadly offer PrEP and PEP.”

Dr. Maria Lopez of Mission Wellness said that it has taken some effort in getting San Franciscans to know that her pharmacy provides PrEP without a doctor’s prescription. She said in addition to referrals from partners, people learn about her pharmacy through a city ad campaign, social media, word of mouth, and PleasePrepMe. She has also reached out to Latino and Black residents through an ad campaign for PrEP and drawn a higher percentage of these populations than in the city as a whole.

It’s unclear whether pharmacies in other parts of the state, including PrEP deserts, will go to such lengths to inform the public that they provide PrEP through SB 159. It’s possible that larger chains might advertise on gay hookup apps, like Grindr and Scruff. Those platforms feature ads from telemedicine apps, like Plushcare, NURX and the gay-focused Mistr, which provide on-demand doctor’s “visits,” PrEP by mail and, in some cases, home self-tests. These telehealth apps are gaining in popularity and may be an even more important link to PrEP for people in PrEP deserts, both in California and the rest of the U.S.

All advocates for SB 159 have admitted that it has some kinks to be worked out, and Hopkins said it’s a good “foot in the door” toward greater use of potentially lifesaving HIV prevention meds. But with all the ways the law might not work as expected, a question looms: Why is it so hard to provide access to meds to prevent a disease that’s a public health crisis? The answer, says Hopkins, is the for-profit health care system, which incites “turf wars” on the part of some doctors and the California Medical Association – who, he says, oppose laws expanding the role of pharmacists because it infringes on their ability to get paid. The CMA initially opposed the bill, because it disrupted the “patient-physician relationship,” but the final version of the bill required pharmacists to refer a PrEP customer to a doctor after providing up to a 60-day supply.

“The only way to end HIV is to make access to testing and PrEP universal,” Hopkins says – insurance co-pays and a lack of free public HIV testing services not only make it harder to prevent HIV, they make the case for socialized medicine.

“I did some of my education in England, where you can walk in with a prescription for anything, and it is covered,” Hopkins says. “Everyone is treated the same. It is hard to bring HIV to zero with the health care system we have now.

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2019 Data Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by Capital & Main.]