Wrong races, hidden names among data challenges our team faced with jail mental health project

This project was produced as a project for the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2021 National Fellowship.

Other stories by David Barer and Josh Hinkle include:

Mental competency consequences: the hidden, unreliable data Texas tracks… or doesn’t

Austin court’s redirection of those committing low-level crimes could be saving taxpayer money

Jail waitlist for mental health help hits new record. This plan proposes a statewide fix.

Mental Competency Consequences: The Hidden and Unreliable Data Texas Tracks — Or Doesn't

State of Texas: Leaders consider ‘consequences’ of not tracking state hospital waitlist data

A state hospital death in restraints and seclusion: What happened to Justin Reeder?

State mental hospital backlog grows, new record exceeds 2,500 waiting in jail

‘Horrifying’ wait times for state hospital beds, official says

Despite waitlist record, leaders keep pushing ‘Eliminate the Wait’ plan for state hospitals

Thousands waiting in jail for state hospital beds, is help coming?

Investigative Summary:

For two years, KXAN investigators have explored a growing backlog of people in Texas jails who need mental competency restoration. While an advisory committee has largely focused on finding state hospital beds for that group, our team took a closer look at the backgrounds of individuals on the waitlist to determine trends experts say could help drive down numbers. Our research found data on this topic is often hidden or unreliable – a discovery sparking promise for change from state leaders. The resulting “Mental Competency Consequences” project is supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

AUSTIN (KXAN) – The origin of our reporting began with the Texas Health and Human Services Commission’s reply to a request for public information. We wanted to know the number of people who had died waiting for a space in a state mental hospital. HHSC said it didn’t have that record.

Most investigations highlight what investigators manage to uncover. We inverted that approach for this project. In our examination of shortfalls in the state’s oversight of the state hospital waitlist, we spotlighted unreliable state data and records that aren’t kept, like the race and ethnicity of people on the waitlist and how many are dying each year before getting to the hospital.

Experts and state hospital leaders acknowledge a deeper understanding of the people entering state hospitals — like their race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status — could help identify why they get backlogged in the system. State officials could also learn if certain groups experience disparate outcomes. When we drilled into the data, we found the state and an advisory committee that oversees the waitlist are not yet closely tracking key information.

The state does not know, for example, how many people on the waitlist couldn’t afford an attorney or were experiencing homelessness before they were booked into jail. We also found the ethnicity data the state receives from law enforcement and the courts are not uniformly collected and may not be accurate, which could skew counts of Latino and white populations.

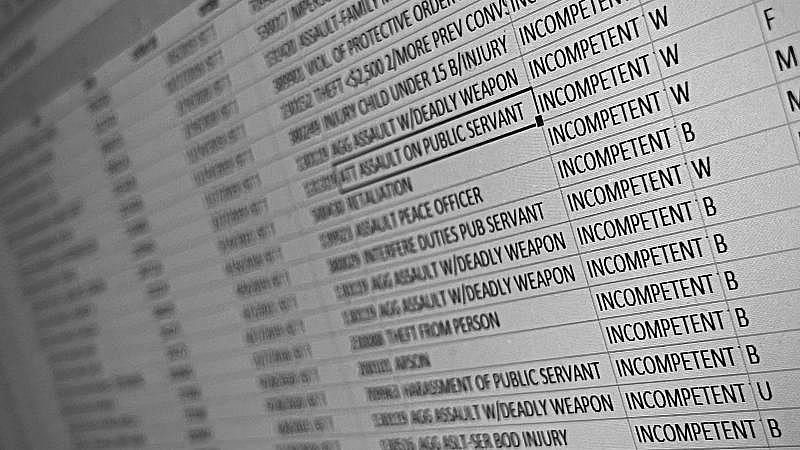

KXAN built its own databases compiled from district clerk records and used them to analyze mental competency details Texas does not reliably track. (KXAN Photo/Josh Hinkle)

To find just how spotty the state’s records are, we endeavored to build a portion of the waitlist database ourselves.

Since the waitlist is secret, we had to find a backdoor to the information.

HHSC said it knows of no other entity in the state with a complete copy of the waitlist. Sheriff’s offices may know who in their own jails are on the waitlist, but we were blocked from getting that information by the HIPAA privacy law, which protects personal medical information from being released to the public.

So, we went to the record keepers of the courts: district clerks. We found judges order incompetent people to be sent to a state hospital for restoration. Those orders are public court documents. In four of Texas’ most populous counties, we found district clerks could provide some data showing each time that type of order was issued.

Unfortunately, Texas’ district clerks do not have a uniform method for keeping records. Each county’s district clerk runs their office differently, and offices use different record-keeping software and techniques.

The data we were able to obtain varied from county to county, so we had to fill in the blanks — thousands of them — to analyze the information. We found discrepancies in racial and ethnic data, and a lack of information about the economic status of individuals on the waitlist.

//Finding deaths

With district clerk data in hand, we turned to custodial death records compiled by the Texas Justice Initiative, a nonprofit that aggregates and provides criminal justice information to the public for free. We merged those two datasets and found matches: individuals found incompetent to stand trial who also died in custody.

We discovered dozens of potential deaths of individuals on the waitlist since 2015. Using court and jail records, and media reports, we whittled that down to about a dozen cases, and confirmed at least eight of them. In the remaining handful of cases, it appears highly likely from court records that the individuals died on the waitlist, but we could not reach an attorney or family member for confirmation.

Mental competency consequences: the hidden, unreliable data Texas tracks… or doesn’t

But there are likely more than a dozen people, potentially many more, who died in the past five years in jail while waiting for a state hospital bed. We analyzed only a handful of the state’s most populous counties, but Texas has 254 counties and more than 37,000 people housed in jails pretrial and charged with felonies, according to the Texas Commission on Jail Standards.

We focused on four of the state’s largest counties because we were able to get usable data from them, and they hold a sizable portion of the people found incompetent to stand trial.

What’s more, our district clerk data did not show misdemeanors. There were likely incompetent individuals who our analysis didn’t catch, like Janice Dotson, who was charged with a misdemeanor and died in jail after a doctor determined she was incompetent to stand trial, according to federal court records.

We didn’t confine our search to just data. We also scoured media reports, and in Dotson’s case, heard of her story by chance during a separate interview with the family of Fernando Macias.

Both Dotson and Macias died in Bexar County custody in December 2018. Dotson and Macias’ families have sued the county over their deaths.

Download the Macias family lawsuit here

We heard other harrowing stories of individuals across the state enduring disturbing conditions in solitary confinement, spiraling deep into despair and ultimately dying before seeing justice or a mental hospital.

Those stories pushed us to continue digging into the waitlist. We even found a member of the state’s waitlist advisory committee openly concerned about whether it’s legal to hold incompetent people in jails.

Question of constitutionality

At an October meeting of the Joint Committee on Access and Forensic Services, committee member Jim Allison called into question the constitutionality of holding people on the waitlist who have not been convicted of a crime.

“It’s not, in my opinion, providing them with humane or even constitutional treatment, to hold them in a jail,” said Allison, general counsel for the County Judges and Commissioners Association of Texas. “If they’re being held, particularly in an understaffed county jail, they’re certainly worse off than if they were held in understaffed state hospital.”

Jail waitlist for mental health help hits new record. This plan proposes a statewide fix.

The JCAFS is an advisory board under HHSC. Its members have formed internal subcommittees to work on improving and expanding their data collections. With more comprehensive data, the committee could better understand the forces driving the waitlist.

HHSC and JCAFS do monitor the total number of individuals on the waitlist, the average and median number of days they wait and the number of available state hospital beds. That information is available publicly.

JCAFS called for race and ethnicity data to be tracked in November 2020. We learned HHSC began collecting that information months later but had not made it public. KXAN obtained the breakdown, which an HHSC spokesperson said would be incorporated into the committee’s public data dashboard in 2022. The information we obtained was broad, only showing the aggregate numbers of each race and ethnicity of people waiting for a state hospital bed. The data did not break down waitlist statistics by county or by race and ethnicity by showing, for example, the average amounts of time waiting for each race in a particular county.

We decided to dig into the race and ethnicity of people on the waitlist ourselves.

Tracking race and ethnicity

With reliable data, the state could better understand the forces driving the ballooning waitlist, said Lynda Frost, a mental health and criminal justice expert, attorney and former assistant director of the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health, a University of Texas foundation that works to improve mental health in the state.

“We know that people are not treated equally across our criminal justice system. Across races, we know that there are differences that data do show in how people are treated based on race and ethnicity,” Frost said. “When we look at specific parts of that system, for example, competency restoration, we want to know how that plays out. And if we don’t have that data, it’s harder to figure out what we can do to ensure that our justice systems are truly just.”

In response to KXANs questions about how the Bexar County Sheriffs Office records an individuals race in its booking system, a spokesperson provided this image showing the electronic booking systems race options, including nationalities Chinese and Japanese, as well as an Indian option. (Bexar County Sheriffs Office Photo)

We focused our data collection on Bexar, Dallas, Harris and Travis counties — some of the largest in the state that were also able to provide data. We also included Tarrant County in our search for deaths but were unable to get raw data from Tarrant to analyze its numbers for race, ethnicity and appointed attorneys.

What we found were scattershot approaches to recording race and ethnicity information by district clerks, local law enforcement and jails.

District clerks offices said they don’t independently collect race or ethnicity information and that information is provided by law enforcement.

Using district clerk records and online search tools, we found Harris and Dallas counties’ clerks offices did not have public records showing the ethnicity of people charged with felonies. We found Travis and Bexar counties’ do collect ethnicity, but a case-by-case examination found dozens of people with the most common Hispanic last names were labeled white and non-Hispanic.

As we looked through Dallas County, for example, we found no court records that identified individuals as Hispanic, yet dozens of individuals found incompetent in that county had common Hispanic first and last names. A Dallas County District Clerk spokesperson said the county relies on law enforcement arrest affidavits and booking information to determine the race in its records.

“The Dallas County Sheriff does have a Hispanic ethnicity identifier in the Adult Information System (AIS) which she uses to manage book-ins and the jail’s population, but my experience has been that the identifier is used inconsistently at best,” said Gary Fitzsimmons, a Quality Assurance Administrator with the Dallas County District Clerk.

We found further inconsistencies between sheriff’s offices. In Travis County, a spokesperson for the sheriff’s office said when a person is booked, they use the exact race and ethnicity recorded by the arresting officer, and the choices are “Alaska Native/American Indian, Asian/Pacific Islander, Black, Hispanic/Latino or White.”

The Bexar County Sheriff’s Office said it follows a statute that requires using the same race options as Travis County provided. Bexar County Sheriff’s Office also sent a picture of the options in its computer booking system for recording race, including “Asian, Black, Chinese, Indian, Japanese, Latin, Other, Unknown, White.”

When taking into account the differences in recording race and ethnicity between county law enforcement and courts, it is not clear how reliable HHSC’s waitlist data can be.

Measuring income and housing

Analyzing the socioeconomic status of individuals on the waitlist was also tough, but we knew from interviews that income and housing have a correlation with whether people achieve long-term mental health improvement.

“Homelessness — housing in general — is a very important factor in maintaining somebody’s wellbeing. If we look at outpatient competency restoration, housing is a key issue,” Frost said. “If we’re not tracking the housing needs of people, that’s going to be a problem. So, I think that quality data is essential.”

How Austin low-level crime court helps ‘frequent utilizers’ experiencing homelessness

Since the state didn’t have a county-by-county breakdown of that information, we created a dataset ourselves. To do that, we identified and counted individuals who could not afford an attorney and were appointed one by the court.

We individually searched more than 2,230 cases in Harris, Bexar and Dallas counties to find which incompetent individuals were appointed an attorney. Travis County provided all necessary data, and we were able to merge it without having to search individual cases for additional details.

//We found the percentage of people experiencing homelessness on the waitlist in Harris and Travis counties by using defendant addresses listed in district clerk data. People experiencing homelessness were labeled as “homeless” or “transient” or used a homeless shelter for their address. The district clerks in Bexar and Dallas counties did not provide address information, so we couldn’t calculate homeless statistics for those counties.

JCAFS committee members said they hope to display race and ethnicity data on their public data dashboard at their next quarterly meeting in January. Committee Chairman Stephen Glazier also told KXAN that understanding a person’s housing status is critical information, and he would make it a priority to have the committee explore gathering data including that information.

[This story was originally published by KXAN.]