Reporting on juvenile incarceration in Arkansas hands down hard lessons

Reporting on juvenile incarceration in Arkansas hands down hard lessons.

Months ago, I set out to find out whether Arkansas failed the kids it incarcerated. Did youths get enough support when they returned home from their parents, their schools, their communities? How did the trauma endured during detention affect them?

While reporting on the juvenile justice beat for about two years, youth advocates, public defenders, juvenile re-entry workers and probation staff told me too many kids slipped through the cracks. Lawmakers didn’t adequately fund state-run “aftercare” programs designed to help children after they got home, they said. Instead, more money was spent on “residential treatment” — essentially jailing kids.

I looked at the numbers. The Youth Services Division spent about half of its entire budget locking up children. Its aftercare budget remained stagnant for over a decade. In many jurisdictions, aftercare workers used cookie cutter re-entry plans for kids.

I learned three key things when embarking on this project. (And I felt fully a lesson I already know when doing long-term projects: Avoid rabbit holes and consult your editor frequently, as in weekly or daily, if needed.) They are:

Six months isn’t enough time to examine first-hand the “long-term” effects of a system, at least not from scratch.

I got through to some Arkansans directly affected by youth incarceration — those interviews were illuminating. But I just wasn’t able to immediately talk to the 50 or 100 kids I had planned on when I set out.

I felt increasingly unsure about being able to answer the question: Was Arkansas’ aftercare system failing kids leaving juvie? I knew it was likely to be true, based on national research and the state’s youth recidivism numbers, but I needed more voices, and I needed more time.

How could I say whether a system was failing if I only talked to kids one month out or even six months out? What about one or two years from now?

I learned that projects asking questions about long-term effects need more time. I should have had at least 10 people who were already released from juvie, those who were already committed to sharing their stories with me, when I applied for this fellowship.

I still plan on answering my initial questions, but don’t expect those stories to be published until May.

Community engagement can be tough.

As reporters, we know reaching those in marginalized communities is a challenge, especially when juvenile court records are totally sealed from public view, as they are in Arkansas and many other places.

But in my case, it seemed like nothing was working. Crowdsourcing tips from ProPublica reporters weren’t yielding the results I hoped for. Parents and those who were incarcerated in the state’s youth jails weren’t responding to my digital engagement efforts.

The newspaper didn’t lift its pay wall on my daily stories related to juvenile justice, making it harder for readers to respond to embedded surveys that asked people to consider sharing their stories of youth incarceration and their contact information. Tweets and Facebook posts went mostly unanswered. There were no active Facebook groups for Arkansas families entrenched in the juvenile justice system.

I failed to recognize early enough that this digital outreach wasn’t effective enough. Arkansas, overall, doesn’t engage in social media or have the same level of Internet access as other places do. It may be that juvenile incarceration may be too embarrassing for people to talk about, especially teenagers, and is not as openly shared.

Advocates and attorneys also gave me numbers to people who first said they’d talk to me, but wouldn’t return my calls or answer me when I knocked on their doors. Sometimes their addresses had changed. Showing up at courthouses when juvenile cases were being heard also wasn’t effective without someone the families knew or already trusted to link us.

Don’t stall important sidebars. They can be great seed stories.

I ended up with a strong series of stories, but in hindsight they should have been published as they presented themselves.

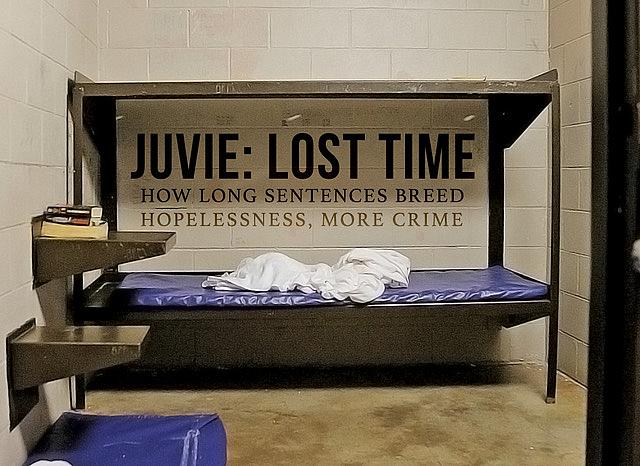

I noticed a recurring issue as I talked to my smaller sample of parents and children. These children were jailed for long periods of time. They waited for months in county-run juvenile jails, waiting for a spot at longer-term, state-run youth prisons, where they could receive the treatment needed for their release. They lost weeks and months before getting the help and beginning their sentences. And when their sentences finally began, youths and lawyers reported that release dates were pushed back, for months on end, for minor rules infractions.

I knew about the studies that found youth sentences longer than six months caused more harm than good. I saw how that could tie into the overall idea of re-entry, but instead of tackling that story first, I just kept it as a side-note for months.

I should have written the first story of the “Juvie: Lost Time” series months earlier than I did, instead of sitting on it.

The story resulted in change and an unusually quick response from the Division of Youth Services. (The agency announced it would cut its sentence lengths to a maximum of six months in most cases. Before, kids were being jailed as long as two years.)

And the story ended up leading me to more families and sources. People that could’ve helped me answer my original question about incarcerated children’s outcomes.

For instance, as a result of this series, I established a stronger rapport with a key juvenile justice advocate in the state. Now, we’re working together to hold a public forum, in collaboration with Arkansas’ two leading advocacy organizations and juvenile public defenders, to speak with families involved in the youth justice system. Similar forums have had better success in the past attracting affected people than crowdsourcing via the website or social media.

Because of my stories, one lawyer reached out to me and tied me to a mother whose son was put on juvenile probation and was being ignored by his school district. One key part of my initial thesis was to prove how schools fail kids, beyond an increase in school-based arrests and talk from local policymakers. Now, I have a family, two sons, and potentially more families that could use more support from schools.

I hope this helps any other reporters hoping to write similar stories. If you have any questions, feel free to contact me at acurcio@arkansasonline.com.