How well is ‘housing first’ working to reduce homelessness in Los Angeles?

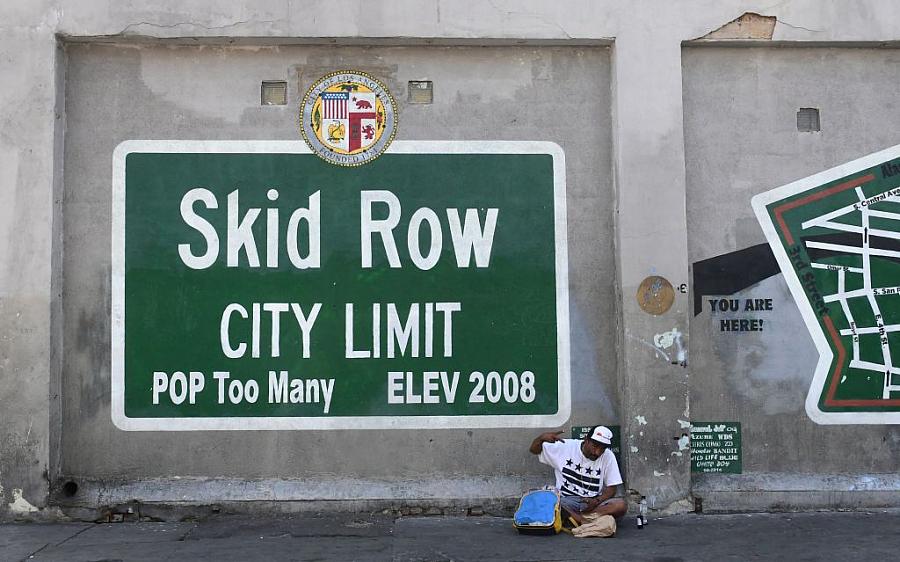

(Photo: Frederic J. Brown/AFP via Getty Images)

Leaders on the front lines of the campaign to eradicate homelessness in greater Los Angeles are cautiously celebrating the rewards of health-driven policies of the last five years known as “housing first” and “harm reduction.”

The policies call for providing permanent dwellings and support services as quickly as possible, instead of expecting homeless people to conquer mental health or addiction problems while living on the street before they can qualify for housing.

“The numbers of folks who have gotten off the street has increased dramatically — approximately 15,000 to 20,000 have exited yearly in the past couple of years,” said Mike Alvidrez, CEO Emeritus of the Skid Row Housing Trust, a leading nonprofit serving homeless people. Alvidrez was among a panel of leaders and experts discussing homeless solutions at the 2020 California Fellowship this week, which was moved online due to the coronavirus outbreak.

During the discussion, panelists lauded the good news that 133 once-homeless people in the L.A. area are finding a place to live every day.

But there is a hitch: for those 133 people getting out, 150 new people are falling into homelessness daily.

“We have numbers that any city would be proud to boast about, but until we turn off the spigot of people falling into homelessness, we’re going see the same results,” Alvidrez said. “It looks like nothing is happening when in fact people have implemented these new programs that have shown remarkable success.”

He and fellow panelists were weighing in at a moment of surging homelessness, with the city and county of Los Angeles homeless numbers increasing by 16% and 12% respectively from 2018-19. Yet even on Skid Row, a 50-block area in L.A. where many of its 5,000 homeless people live in encampments, some lasting achievements have been made.

One crowning jewel is Star Apartments, which offers permanent dwellings to 102 formerly homeless people in a luminous building with a medical clinic on the premises. Star Apartments demonstrates the value of providing access to services for people with acute health needs resulting from years of unsheltered living.

At Star Apartments, “Your mental health provider is an elevator stop away,” said Alvidrez. The building also serves as the headquarters of L.A. County’s Housing for Health division, which has spearheaded the housing-first movement, relying on 80-plus street outreach teams that address medical and social problems and build trust with Skid Row denizens to usher them toward more permanent housing placements.

Housing has emerged as a prescription for better health, given that street life compromises physical and mental wellbeing and reduces average lifespan to 48 for women and 51 for men, said panelist Cheri Todoroff, director of the L.A. County Housing for Health program.

In addition, Todoroff said that her office is dramatically reducing public expenditures on jails, shelters and emergency medical care, citing a study by Rand on the cost-savings of the housing first model.

“It is over 40% less expensive to place someone in permanent supportive housing than to leave a person on the streets,” she said. “We get people connected to housing without preconditions. Our philosophy is: The most important thing is to get someone into housing, to have that shelter, then get them connected to all the services they need.”

And yet despite progress in treating the health challenges of homeless people, formidable obstacles remain, the panelists agreed.

One problem is that it takes too long and costs more than it should to build affordable housing, Alvidrez said, citing California’s “slow growth” land-use policies that delay the development process and discourage building density needed to integrate services in living spaces.

Other impediments include labor and environmental restrictions related to construction, as well as the confusing patchwork of funding. For example, Star Apartments required 21 funding sources. Then, there are myriad bureaucratic demands to prove that the residents are indeed homeless, as they claim.

“We’ve created a paper chase of documentation and certification which impede the ability to get people living on the streets off the streets in an expeditious way,” said Alvidrez, blaming “a phobia that a millionaire is pretending to schizophrenic and homeless.”

Another hindrance is a pushback against housing first and harm reduction policies led by the Trump administration and some local governments and mission leaders. Some favor adding more requirements before someone can be housed, ranging from proving sobriety first to participating in mandated treatment and counseling programs. Those who favor a carrot and stick approach argue that otherwise homeless people refuse services — presumably counseling, job training and addiction treatment — and that disincentives are needed for non-compliant homeless.

Panelists lambasted coercive measures to force programs on people experiencing homelessness. They said services and programs are vital to success, but case workers need to offer rather than impose them on homeless people.

“The services are important; they keep people housed, but it’s a matter of how you build trust,” said Amy Turk, CEO of the Downtown Women’s Center, founded in 1978 to address female homelessness, which has risen dramatically.

She and others said programming for women hasn’t caught up to demographic changes.

“We’re living in a social services environment that was built for men,” Turk said, noting that 37% of women who took part in her organization’s recent survey would prefer all-female service environments.

Female homelessness now constitutes about a third of the overall population, said panelist Gary Dean Painter, director of the Homelessness Policy Research Institute at USC.

He added that Latinos have always been disproportionately underrepresented among people experiencing homelessness, though there is early evidence of an uptick, as well as more cases of families living in cars.

Painter, like his fellow panelists, agreed that emerging solutions in homelessness policy can only stem the tide so long, and that at some point, root causes need to be addressed.

“There are 14,500 chronically homeless in L.A. County,” he said, referring to those who have been homeless longterm. “But only 9,960 units of supportive housing in the pipeline.”