Amy DePaul

Public Health Reporter

Public Health Reporter

I cover public health, ethnic health and health disparities in Orange County, Calif. at VoiceofOC.org, which is a nonprofit investigative news website. I also teach in the Literary Journalism program at UC Irvine. Recent awards include the Los Angeles Press Club, Orange County Press Club, National Education Writers Association and the Council on Contemporary Families.

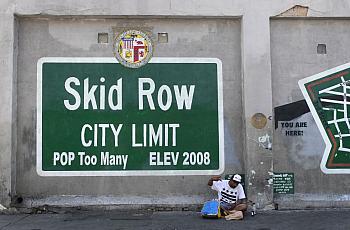

Leaders on the front lines of the campaign to eradicate homelessness in L.A. are cautiously celebrating the rewards of the health-driven policy known as “housing first.”

Homelessness is a health crisis, and the clock is ticking. With homeless life expectancy between 42 and 52, and half of the nation's homeless at least 50, it's not surprising that Orange and several other California counties have seen a dramatic rise in homeless deaths in recent years.

How much does prosperity mitigate race-based health disparities? Orange County's African-American community is relatively wealthy and has a high rate of access to medical care, particularly compared to other ethnic communities in the area. Yet blacks fare worse on a number of key health outcomes.

Known as bodega clinics or storefront clinics — these doctors' offices are incredibly popular in Orange County's Latino neighborhoods. But public health officials harbor a number of concerns about such "bodega" clinics.

With all the attention that domestic violence has received of late, the unique struggles of immigrant families beset by domestic violence have remained largely overlooked. Here's a look at a 3-part series that I wrote on the dynamics of domestic abuse in immigrant families.

My series for Voice of OC on immigrants' health decline as they live in the U.S began with a study that got my attention. It showed that life expectancy rates in the Orange County were higher for Latinos than whites. I was surprised for a couple reasons.

Asian-Americans are now more likely than Caucasians to suffer from type 2 diabetes. The problem follows the pattern of the immigrant health paradox, in which immigrants arrive in better health than the native-born U.S. population, only to see a decline by the next generation.

Low-income Mexican immigrants might be healthier than the overall U.S. population on some measures, but that health advantage fades as immigrants adjust to life in the U.S. That in turn can have worrying consequences when it comes to Latina birth outcomes.

Low-income Mexican immigrants with little formal schooling are healthier than the overall U.S. population, according to a number of measures. But once in the U.S., they lose their health advantages within a generation, despite the improvement in their standard of living.

Good health is almost always associated with wealth and education, and yet low-income, newly arrived Latinos with neither of these are generally healthier than whites by a number of measures - what's known as the “Latino Health Paradox.” But within decades of their arrival, their health declines.