SF Has Fought Homelessness With No-Bid Jobs. Here’s How Urban Alchemy Has Used Them As a Springboard (Part 1)

This story was reported as part of a project for USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this project include:

The Ansonia Hotel, a former youth hostel, is being converted to housing for formerly homeless people. In February, San Francisco awarded local nonprofit Urban Alchemy an $18.7 million no-bid contract to run the site

(Photo: Alex Lash)

Walking north, away from San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood, you go from some of the most desperate street scenes in the United States to one of the city’s toniest enclaves, Nob Hill. About halfway up the hill — some local wags call this middle ground the Tendernob — you might catch a quick glimpse of a former youth hostel, the Ansonia, at 711 Post Street.

The Ansonia is closed for now, but it should soon be full of activity. City officials recently voted to turn it into temporary housing for up to 250 formerly homeless San Franciscans. That decision — and questions from those same officials about the $18.7 million contract awarded to Urban Alchemy, a local nonprofit, to run the Ansonia — are at the heart of a palpable tension right now in San Francisco.

The city has more money than ever to combat its homelessness crisis — a $1.2 billion two-year budget bolstered by federal and state funds — yet there’s skepticism about that money being put to good use.

“San Franciscans are frustrated, and rightly so, that after multiple decades and many billions of dollars spent to ‘solve homelessness,’ thousands of unhoused people continue to sleep on the streets night after night,” Sup. Rafael Mandelman said last month, announcing a new homelessness initiative. “It’s reasonable to expect clear improvement … and frankly people are not seeing that.”

Mandelman’s criticism comes as a corruption scandal continues to take down City Hall officials like a slow-moving cascade of dominoes, all tied to donations from and relationships with city contractors. Neither the homelessness department nor their contractors have been involved or implicated, but as The Frisc has reported, the six-year-old department has been taken to task for lack of oversight, shoddy contract management, and personnel turnover. It is the only major city department that doesn’t have a formal oversight commission.

At a February hearing about the Ansonia and the $18.7 million contract, Sup. Ahsha Safaí asked Emily Cohen, a top city homelessness official, this question: “If things aren’t going well or are mismanaged, how does the department handle this?”

On one level, the supervisor was voicing concerns that others, from his board colleagues to nearby residents and businesses, were also asking: Is the nonprofit getting this contract — a no-bid contract, no less — ready for this high-profile job?

At the same time, he was addressing recent history. Since 2019, SF’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing (HSH) has leaned heavily on no-bid contracts to create housing and services, part of a strategy to treat homelessness as an emergency. In this era, no-bid contracts awarded by HSH have jumped, as a percentage of total contracts, from 1 percent to more than 40 percent.

Officials like Cohen say oversight mechanisms are in place, and that past criticism of HSH practices have been corrected. But inspection of dozens of records requested by The Frisc, including contracts and oversight reports, shows that those guardrails have gaps and weaknesses.

Urban Alchemy, the SF nonprofit at the heart of Safaí’s query, is among the organizations benefiting the most from this new era. The group hires people who have experienced homelessness, substance abuse, or incarceration. Its first job in the city, handed off from a parent organization, was in 2018 managing and cleaning portable toilets.

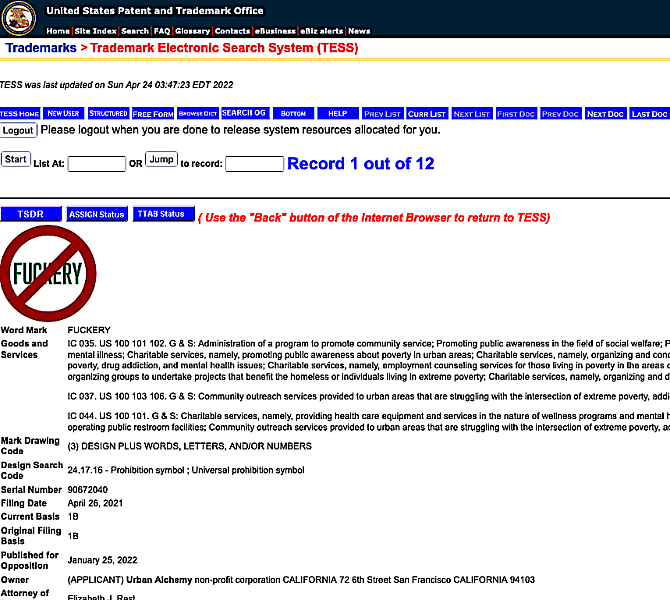

On its website, the group uses a saltier description of its approach: ‘No fuckery.’ It has even applied to trademark it.

It has grown quickly to do much more in SF and other California cities. Its employees walk troubled streets as “ambassadors,” manage city-owned tent sites and service centers for the unhoused, and help run hotels converted into emergency pandemic shelters. The organization says its operating revenue for the 2021–22 fiscal year is $43 million, a fourfold increase over its 2019 reported revenue, which is its last available IRS filing. (It has received an extension and has yet to file its 2020 report.)

This rapid expansion has come “as governments, universities, businesses, and community organizations ask us to help calm chaotic places,” according to the organization.

On its website, the group uses a saltier description of its approach: “No fuckery.” Among its several definitions of the phrase: “It’s shorthand for anti-bullshit. It’s a stance against injustice. It’s holding ourselves and others to account.” (In fact, they’ve applied to trademark it as a logo.)

From the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office website.

(The Frisc requested an interview with Urban Alchemy CEO Lena Miller, who declined. The organization responded instead to written questions. All comments from UA in this report came via email through a spokesperson, Michael Clinebell.)

At the Ansonia, Urban Alchemy will run the entire show: manage the five-story building, maintain security inside and on the block outside, and help up to 250 residents connect with services such as mental health care. “I’m not aware of a model like that,” Sup. Matt Haney, whose district includes the Tenderloin, said in the February meeting.

At that time, Cohen acknowledged it was new for HSH — a chance to see if UA could build trust with people on the street then get them inside for housing and services. “We’re very excited about testing this out,” she said, and added that UA has been “an incredible partner in many projects for us,” including management of an emergency hotel during the pandemic. That description, however, doesn’t tell the whole story.

The no-bid era begins

For homelessness in San Francisco, 2019 was a pivotal year.

The city counted more than 8,000 unhoused people, a 15 percent jump from the prior tally. While home prices and rents kept climbing, the homelessness emergency — officials had declared one in 2016 — was getting worse.

Also in 2019, Mayor London Breed and the supervisors extended a little-used ordinance that allowed the homelessness department to offer no-bid contracts and move faster to open shelter and services.

From 2016 through 2018, only 1 percent of the department’s contracts were no-bid. From the beginning of 2019, it’s 43 percent.

Since the beginning of 2019, the department has issued $1.5 billion in total contracts. No-bid contracts have accounted for nearly half of those dollars, or $721 million.

The pandemic is a major reason for the increase. When COVID struck, the city had to move fast to meet rapidly changing circumstances. For HSH, the no-bid provision has cut the time to open a shelter or service by three to five months, according to Cohen, who is HSH’s deputy director of communications and legislative affairs. In a town where every development can trigger all sorts of fights and delays, that’s a big improvement.

Urban Alchemy isn’t the only nonprofit getting big no-bid contracts. Two long-time providers are also among the top recipients: Tenderloin Housing Clinic (THC) — $135 million in no-bid contracts — and Episcopal Community Services (ECS) — $115 million in no-bid contracts.

Since the beginning of the “no-bid” era in 2019, THC has received six no-bid contracts out of a total of eight, while 17 of 38 contracts for ECS have been no-bid, according to the city controller’s SF OpenBook data (as of April 10, 2022). ECS has run nine emergency hotels during the pandemic. Each has been providing housing and services in SF for four decades.

Only four years old, Urban Alchemy clocks in with the third-largest total, $68 million. Nearly all UA’s HSH contracts since 2019, eight of nine, have been no-bid.

No-bid contracts “may make sense” when there aren’t “many folks wanting to do the work,” says Dan Lindheim, professor of city and regional planning at the Goldman School of Public Policy at UC Berkeley.

Lindheim was director of Oakland’s Community and Economic Development Agency in 2007 and Oakland’s city manager from 2008 to 2011. He negotiated many contracts for city development and services, and says there need to be no-bid safeguards.

For example, during his Oakland tenure there was a $100,000 cap, Lindheim said. San Francisco has no cap. The city charter does require a Board of Supervisors vote to approve contracts of $10 million or more.

The SF ordinance governing the shelter emergency no-bid contracts is slated to sunset either in 2024 or when the city’s homeless count dips below 5,250 people. In all likelihood, 2024 will come first. But as in 2019, officials could ostensibly extend the no-bid allowance again.

Boilerplate oversight

Trying to untangle homelessness, San Francisco’s knottiest problem, HSH has had many problems of its own. The department’s record came under fire in a Budget and Legislative Analyst’s report in August 2020, and the interim director at the time agreed with all the report’s recommendations.

Leadership has tried to be more accountable, with mixed results. For example, The Frisc reported more than a year ago that homeless folks have waited months for housing despite gaining approval, while hundreds of units sat vacant. The department said it would reduce the bottleneck, but it has gotten worse.

Last fall, new director Shireen McSpadden promised to revamp the system HSH uses to prioritize people for housing. (The Frisc reported on its flaws in 2019.) McSpadden also pledged that people working for HSH need to look more like the people they’re serving; SF’s unhoused population is disproportionately Black, roughly 50 percent, compared with a general city Black population of 5.6 percent.

Oversight is another concern, whether from outside looking in — there is no formal oversight commission, unlike other major city departments — or its own internal controls over contracts, housing inventory, and more.

Those concerns only grow as the budget expands and the department continues to depend on a network of more than 50 nonprofits to carry out core responsibilities. As The Frisc recently reported, SF agencies typically spend 45 percent of their budget on in-house salaries and benefits; HSH only spends 5 percent.

When Sup. Safaí brought up oversight during the February hearing about the $18.7 million Ansonia contract, Cohen said the department can always take “corrective action” or even terminate a contract; she then stressed that HSH submits an annual report to the Board of Supervisors that lists all no-bid contracts.

The annual reports, however, provide no evaluation, just boilerplate information: contract date, provider name, dollar amount, and a general description of services.

Additionally, The Frisc has found that HSH has failed to include some no-bid contracts in the annual reports.

It’s unclear if the supervisors are paying attention. The Frisc contacted all three members of the oversight committee; none responded to questions about the annual reports or HSH oversight in general. Neither did supervisors Safaí or Aaron Peskin, whose district includes the Ansonia, and who said recently that he found the Ansonia no-bid contract “mysterious.”

Staff writer Kristi Coale (@unazurda) writes about homelessness and more for The Frisc. She reported this story as a USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2021 Data Journalism fellow.

[This story was originally published by The Frisc.]