‘How did this happen to my son?’

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2021 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this project include:

PART 1: Texas schools don't have enough mental health providers, and leaders are failing to fix it

PART 2: ‘How did this happen to my son?’

EPILOGUE: How can schools provide mental health services for students? Here's one expert's recommendations.

Mark Mulligan, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer

Dallas Garcia was sure the phone call about her teenage son was a prank.

Holding a hand to her unoccupied ear to drown out cheers at her 7-year-old son Jagger’s football game in Alvin, Dallas climbed beneath the bleachers.

She asked the woman to repeat herself.

“Your son, Fred, was in an incident,” a woman said. “You need to come now.”

An incident? But her son was in jail.

What could possibly have happened?

Dallas Garcia describes the loss of her 19-year-old special needs son, who was killed in an incident with an inmate in the Harris County Jail in 2021. Video: Mark Mulligan/Houston ChronicleFred, who was 19 and had an IQ of 62, had been struggling for years with depression and anxiety, unable to cope with the sudden nastiness of his peers and not enough mental health resources in high school. He started threatening suicide. He started running away. He started living on the streets.

So when Fred was arrested three weeks before Halloween last year, Dallas thought jail was a godsend — a place where his deteriorating mental illness would finally be addressed, a place where he wouldn’t hurt himself or be hurt by others.

Instead, a fellow inmate at Harris County Jail allegedly beat Fred so severely that he was brain dead by the time she arrived at Ben Taub Hospital 40 minutes later. Sitting at his bedside saying her goodbyes, Dallas shook with anger. Her sweet, outgoing son — who never met a stranger and had garnered the nickname “Fearless Fred” — was gone.

His death on Oct 31, 2021, is a devastating reminder of how mentally ill kids can fall through the cracks: They end up in crisis, on the streets or thrust into the adult mental health system where psychiatric beds are so scarce jail is often the only option.

A Houston Chronicle investigation found that every school district in Texas — including Fred’s — failed to have the adequate number of all four recommended mental health professionals (nurses, psychologists, counselors and social workers) between the 2013 and 2020 school years.

For Dallas, that was just the first breakdown as Fred struggled to cope with getting older.

He didn’t receive mental health services as he transitioned into adulthood.

She struggled to get guardianship of her special needs son.

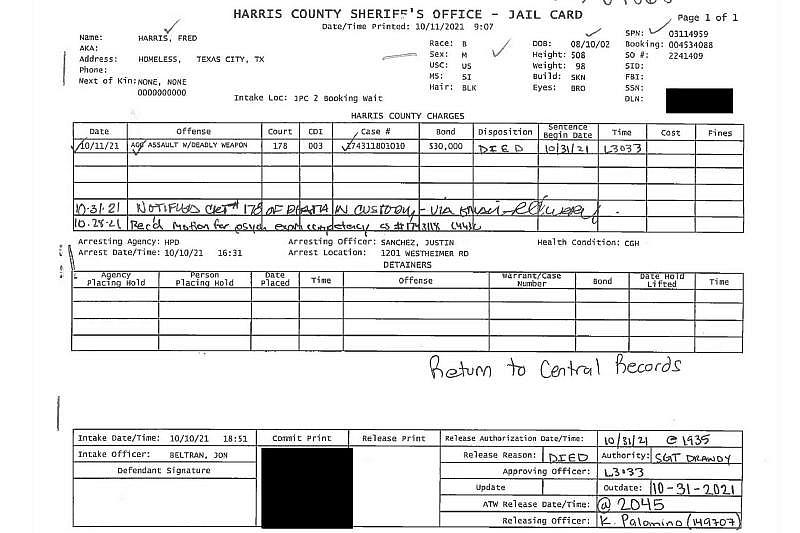

A competency evaluation wasn’t ordered for Fred until more than two weeks after he was arrested.

As the sound of Fred flatlining filled the tiny hospital room, Dallas began to wail.

How did this happen to my son?

August 2002

Galveston

Fred had been alive for just a few days when Dallas’ healthy, 8-pound boy started rapidly losing weight. Doctors at The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston stuck him full of tubes and wires, hoping to get him back on track.

They weren’t sure what happened. But as weeks turned into months, it was clear something was wrong with Fred.

Normal tasks will be hard for him, they told her.

He may never be able to tie his shoes.

He may never be able to read.

We’re sorry.

That wasn’t an acceptable answer. Dallas was a single mom and going to nursing school. Even with a 1-year-old son at home, she fought to get Fred resources.

She transported him back and forth to doctors appointments, where they worked on fine motor skills like picking and pinching.

She got him into therapy and made sure his day care programs were small enough that he received the appropriate level of attention.

She put him in sports and activities that kept his mind and body busy.

He always wanted to do more.

ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

Bonham Elementary

Houston

2008-2013

Fred leaned over the cluttered dining room table, pressing his pencil so hard into the workbook the lead tip kept breaking.

It was the weekend. Fred’s family was gathered at his grandmother’s house playing games and eating hourslong meals.

But Fred’s schoolwork was more important to Asa Garcia, Fred’s older sister. She sat patiently with him, readjusting his fingers around the No. 2 pencil, correcting his spelling and math.

“Repeat after me, Fred: A, B, C, D, E, F, G.”

Fred scrunched up his face in concentration.

“G, A, D, F, C.”

Asa, 13, sighed. Helping Fred could be so frustrating. At 8, Fred still didn’t know the alphabet. He still couldn’t read or write.

When Asa and Dylan, Fred’s older brother, played hide-and-seek, Fred didn’t understand where they went or what he was supposed to do.

They tried to teach him board games, from Trouble to Monopoly, but he couldn’t process the rules. Even Uno was confusing for him — he repeatedly put down cards that didn’t match the color or number, gleefully screaming “UNO!” even when he had more cards in his hand.

At Bonham Elementary, he had a dedicated aide who helped him navigate school — he’d had an Individualized Education Plan, or IEP, since kindergarten. If kids teased him for being different, he had a counselor who was able to intervene.

Outside of school, Asa did the intervening. When kids refused to play basketball with him because of his size, she would use herself as a bargaining chip — offering to join Fred’s team even though she was at least five years older than most of the kids playing.

***

Fred trailed behind his brother, Dylan, as the two marched through the neighborhood in search of bored kids looking to play football.

The two were only a year apart, but no one would know by looking at them. Dylan towered over Fred — a good head taller even at just 11 years old. Dylan didn’t care.

Other boys teased Fred and said he was too small to play. Dylan never made him sit on the sidelines. Fred was an active participant in all their games.

Dylan had heard his mom talk about how Fred was different: That he might not be able to do everything Dylan did, that he might need protecting.

“Go easy on him,” she repeatedly told him. “He might not understand as much as we do.”

But Dylan didn’t really get it. He was always just Fred, the slightly annoying little brother who copied everything his older brother did.

As the group of scabby-kneed boys assembled in the street, Dylan smirked at his brother.

Even if he never caught it, Dylan would always throw Fred the ball.

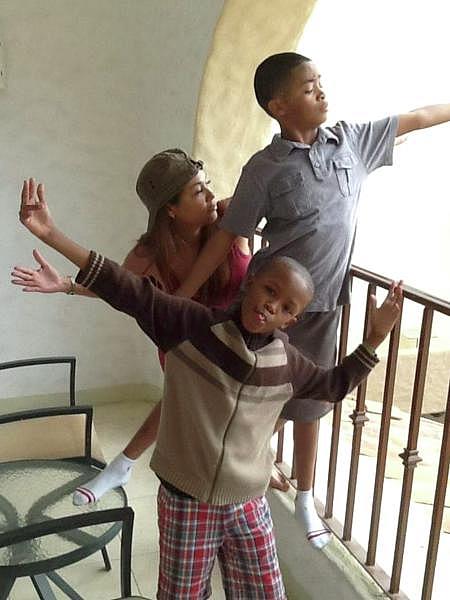

Family photos of Fred Harris with his older brother Dylan and mother Dallas. (Courtesy)

MIDDLE SCHOOL

Houston and Stafford

2013-2016

“KIAI!” Fred screamed as he kicked at his invisible opponent during martial arts practice, his shoes squeaking on the mat.

Fred loved karate. He loved basketball and dance. He loved T-ball and soccer. He loved sports.

Almost every day after school, Fred raced to the gym for hours of activities run by school personnel. Fred was doing well. He had aides helping him and counselors at his disposal.

He had friends and came home from school happy most days. On the rare occasion that kids picked on him, counselors were there to address the situation. Dallas barely had to get involved.

Thinking back to the years of hardship she faced when he was young — all the doctors who said Fred wouldn’t amount to anything — she couldn’t help but smile.

They were all wrong about her little boy.

A home video of Fred dancing. (Courtesy)A group of kids surrounded Fred, pelting him with pinecones and laughing. Fred kept yelling at them to stop, trying in vain to dodge the scaly projectiles.

Dylan was on the other side of the park, playing basketball. He heard the commotion and sprinted to help.

“Stop it, y’all! Stop!”

They didn’t.

Dylan had been protecting his younger brother for years. He stood up for Fred in the classroom when he struggled to spell and in the hallways when he macked on a girl who already had a guy and caused a scene. The park was no different.

“I live with him so I understand he can get frustrating,” his explanations would always start. “But you’re picking on a special-needs kid.”

Sometimes, words were enough. Sometimes, like today, Dylan would have to use his fists.

“I could have taken them, man!” Fred said when the group dispersed.

Fred believed it. Dylan knew better.

***

The January air was crisp in 2014 as Dallas walked Fred and Dylan across the threshold of their new home in the Fort Bend County suburb of Stafford, a moving box on her hip and another child in her belly.

After years of living in a townhouse in Houston, Dallas and her kids would finally have space — and a lot of it.

She thought it would be better for Fred. He’d have a pool. He’d have a yard. She planned for him to go to Dulles High School, where she had heard the special education services were stellar.

But Fred’s fresh start in Stafford turned out to be less than promising. The neighborhood, albeit safe, had less kids for Fred to play with. The pool didn’t get as much use as she hoped.

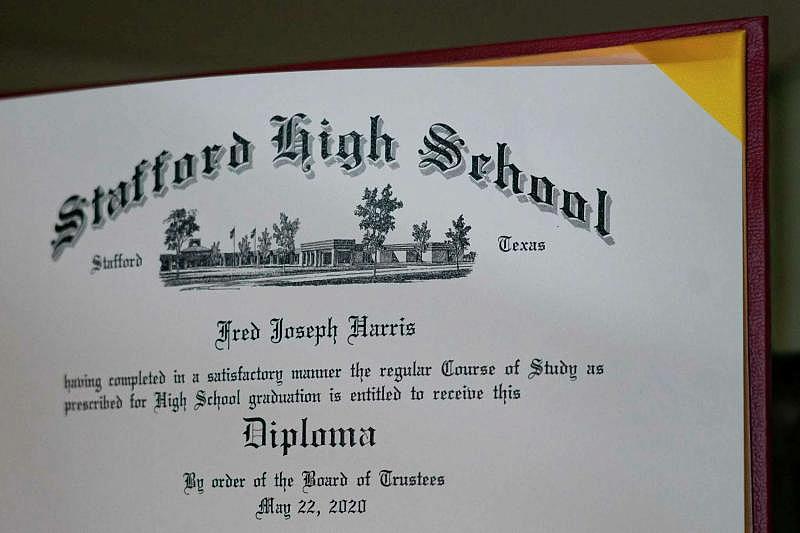

Their new home wasn’t zoned for Dulles, sitting roughly a street outside the school’s attendance boundary. Dylan and Fred ended up at Stafford High School.

Suddenly, her son — who, at 13, could barely write his name and struggled to read — was wandering halls bustling with 1,000 students. Neither of them were prepared for how difficult it would be.

HIGH SCHOOL

Freshman Year

Stafford

2016-2017

Fred came home from school and went straight to his room, blasting music to drown out the negative thoughts swirling in his head. Dallas knocked on his bedroom door.

“Fred, what happened?” she shouted over the music.

“They called me retarded.”

Dallas put her head in her hands. More and more, Fred was coming home in tears. Kids made fun of him for dancing in the hallways even though they cajoled him into doing it.

They made fun of him for being little; for being different.

Mean messages from his classmates pinged his phone during dinner, his bedtime routine or their weekly game nights.

Dallas’ bubbly, outgoing son was drawing inward. And it was breaking her heart.

Dallas had taught her son to turn to a counselor or aide when he got upset at school.

But his freshman year, Stafford Municipal School District had about six counselors and two psychologists to serve its 3,500 students.

That meant there was just one counselor per 567 students and one psychologist per 1,770 students. National advocates say schools should have one counselor per 250 students and one psychologist per 500 students.

There weren’t enough counselors to help him. Without those adults around to diffuse the situation, Fred came home with pent-up anger.

In the past, he had used sports as an outlet. He used to make all the teams at the YMCA. But now, he was too small. He didn’t make any rosters.

“Let’s talk about it, Fred,” she said. “Please let me in.”

But Fred didn’t want to talk. He wanted to wallow.

Dallas had been through the teenage phase with Dylan. That was hard enough. She knew Fred’s would be even more fraught with land mines.

Sophomore Year

Stafford

2017-2018

Fred was more excited than he had been in months — he was talking so fast and inserting so many dance moves into his story that Dallas struggled to understand him.

“I’ve got new friends, and they think I’m cool!’’ he told his mom, beaming.

More than anything, Fred wanted a group of friends. But something about this crew gave Dallas an uneasy feeling. She asked to meet them — it was, after all, standard protocol.

Fred said no.

Then, while cleaning Fred’s room, Dallas noticed her son’s cologne collection was missing.

“Fred, where are your things?” she asked.

“You’re just going to be mad at me,” he said.

Fred’s new friends were taking his things. As more belongings disappeared around the house, Dallas installed security cameras.

Watching the recordings back one night during a work shift, Dallas saw Fred letting his friends into her house. They asked Fred to show them where his mom kept her jewelry. They took his clothes, his Christmas presents, his birthday money.

With a toddler at home, Dallas feared for her family’s safety. She told Fred he couldn’t hang out with these kids.

That angered Fred.

***

Every creak of her 21-year-old house, every footstep on the landing brought Dallas racing to the front door looking for Fred.

Fred hadn’t come home from school that April day. For hours, she’d waited for him to walk through the door, fists full of apologies:

I stayed late at school to work on a project.

I was hanging out with friends and lost track of time.

But she’d called. She’d texted. He hadn’t responded. And now it was dark. Now she was scared. She called the police at 10:08 p.m.

“My son hasn’t come home from school. It’s been hours.”

They told her to remain calm. That they would look at his usual haunts.

“Don’t panic yet.”

Dallas couldn’t help it. Fred had been having more and more trouble at school — the only crowd willing to accept him the wrong one.

She paced back and forth between her living room and kitchen, watching the clock and holding her breath.

At 11:30 p.m. Stafford police officers showed up at her doorstep. There was Fred, holding a greasy paper bag from Sonic.

Dallas took a deep breath. He was safe.

An officer walked Fred up stairs to his bedroom.

“You didn’t grow up like this,” the officer said. “What’s the problem?”

“She doesn’t let me hang out with my friends. She doesn’t let me have my freedom,” Fred said.

Dallas had run away from home when she was 14 and spent all night laying on a bench on the beach staring up at the stars. She was terrified that a meteor would fall out of the sky and kill her.

There was no way Fred would run away again — her sweet little kid had to have been scared the entire time, just like she was all those years ago.

Fred ran away three more times that year.

***

Fred had been gone for two days when Asa’s phone pinged with a Twitter notification. Someone had seen Fred at an apartment pool about a mile from Dallas’ house in Stafford.

Asa felt her body unclench for the first time in days. Dallas, Asa and Dylan had been looking for Fred nonstop, the July heat bearing down on them as they searched gas station parking lots, neighboring streets and the grounds of Stafford High School.

There’d been no sign of him. Asa put out a call for help on Twitter. It had paid off. Asa called her mom, and the two of them raced to the apartment complex.

Fred was happy to see them, acting like it was no big deal that he’d been gone two days without a word.

“I’m hanging out with my friends,” he said of the group of kids Dallas was concerned about. “I’m just swimming.”

Fred didn’t want to come home. Eventually, they convinced him.

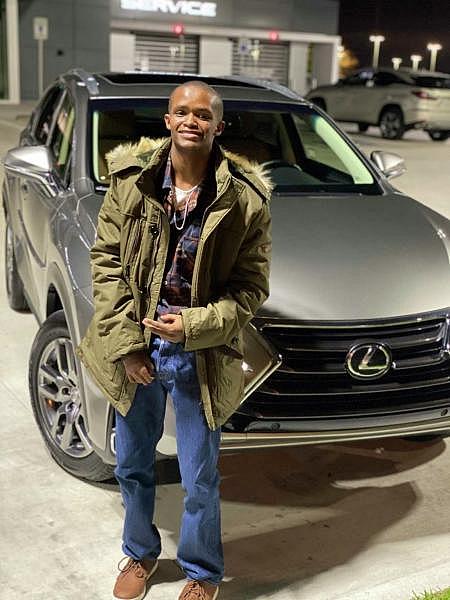

Fred Harris, who had an IQ of 62, stands in front of a Lexus SUV. Fred, who was 19 and had special needs, was killed in an incident with an inmate in the Harris County Jail in 2021. Courtesy/Fred Harris family

Junior Year

Stafford

2018-2019

Fred slammed his thumb down on the Playstation joystick, taking his frustration out on the tiny men with guns on the screen.

“Mom is being so hard!” Fred shouted at Dylan through his Playstation headset. “She won’t let me do anything!”

Dylan had moved in with his uncle in Texas City, but he always made sure to connect with Fred via Facetime or, more often, over a video game.

Usually, Fred would cry. Tonight was no exception.

Fred had repeatedly run away from home over the past year — sometimes leaving in a huff just to show up at school, unshowered and hungry.

And every time, Dallas called Dylan in tears, hoping he could talk sense into his little brother.

“What are you trying to gain from this, Fred?”

Fred never answered, simply repeating the mantra that their mother was controlling — that she was ruining his life.

But Dylan knew better. His mom wasn’t asking Fred to do much. She was just trying to protect him.

“Just do what she asks,” Dylan said through his headset.

But it was December and Dallas had had enough. She thought back to a recommendation made by an officer earlier that year — that Fred might do well in a psychiatric facility with an inpatient program for teens. The past year of outbursts, running away and police knocking at her door weighed on Dallas.

She committed him.

***

Fred and his family had spent the morning bowling, stuffing themselves with pizza and soda to the unmistakable sound of pins crashing at the end of the lane.

It was Good Friday. Dallas’ kids didn’t have school. They were sitting down to play a board game when Fred wandered upstairs to take a shower.

Dallas thought nothing of it. The family played board games every Friday, and Fred was known to drift away when he’d had enough. She kept chatting with her friends.

Then: A knock at the door.

Who could that be?

The crisp uniforms and shiny badges of Stafford Police greeted her. They were there to conduct a welfare check.

“What are you talking about?” she asked.

They told her Fred threatened suicide on Instagram. They needed to see her son to make sure he was safe.

This must be a misunderstanding.

Fred had never mentioned suicide before.

Did he even know what that word meant? Hadn’t they just had a fun morning?

The officers went up to his room, where Fred was sitting on his bed, playing on his phone.

She thought he was mimicking behavior he saw on social media. Still, she knew she needed to have a serious talk with her son.

“Did we not have a good day?”

Fred looked so little sitting on his queen-sized bed.

“Y’all were doing your own thing and you didn’t include me.”

It was a cry for attention. Dallas was relieved.

But Fred’s behavior was alarming. He started saying he planned to starve himself to death. She again put him in a Houston mental health hospital.

She didn’t know if it would do any good.

Seven-year-old Jagger looks up at his mom, Dallas Garcia, as they play the board game Trouble in February in their Stafford home. Jagger's older brother, Fred Harris, loved playing board games even though his low IQ meant he didn't always follow the rules. This is the first time the family has played board games together since Fred's death last year. Mark Mulligan, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer

Senior Year

Stafford

2019-2020

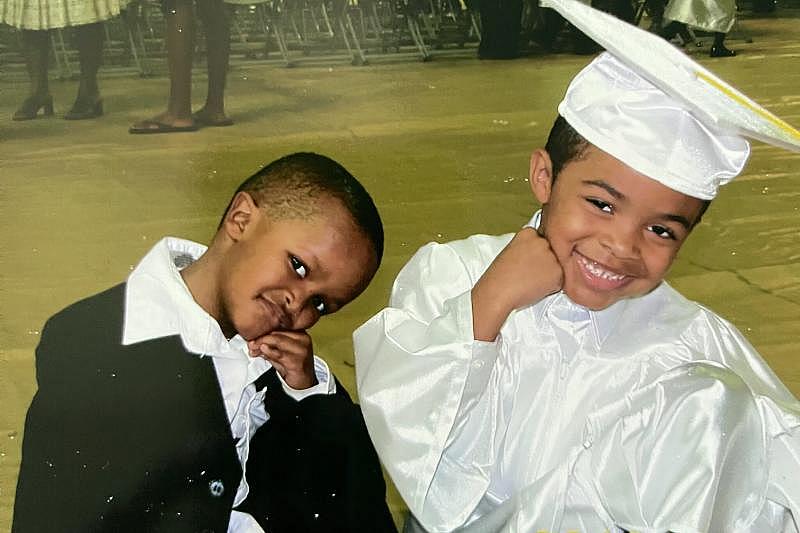

Fred beamed for the camera, a plastic purple lei around his neck and his little brother, Jagger, by his side.

Dallas couldn’t help but tear up: Despite all the ups and downs — the outbursts and the running away — her son had graduated high school.

He even had a job lined up. It’s what they’d both dreamed of for years. But it was also terrifying. Fred was about to turn 18. And she was about to lose control.

If he ran away from home, the cops couldn’t do anything — he would be an adult.

If he got sick, she couldn’t talk to the doctors about his treatment — he would be an adult.

She had started the process of getting guardianship, but it was more complicated than she could have ever imagined.

Because he presented as high functioning, Adult Protective Service officials often struggled to gauge his actual presence of mind. Dallas felt absolutely helpless.

He won’t stop being special needs at 18. Why doesn’t the system allow me to protect him?

Fred Harris celebrates his high school graduation with his sister, Asa Garcia, in May 2020. Fred, who had special needs, was so disappointed that COVID led his high school to cancel prom, his family held a dance in their backyard. (Mark Mulligan/Houston Chronicle)

May 2020

SUN Behavioral Houston

Houston

Dallas could hear the nurse from SUN Behavioral Houston on the other end of line, but the words seemed incomprehensible.

Fred had a mild alcohol and cannabis use disorder. Had she considered a drug rehab program?

Drug rehab? What are they talking about?

Dallas had admitted Fred to the hospital, an inpatient psychiatric facility near the Texas Medical Center in Houston, when he tried to slit his wrists a week after graduation.

By this point, Fred had been diagnosed with major depressive disorder. It was reoccurring. And it was severe.

She knew Fred needed inpatient care. But she had been growing increasingly nervous about Fred’s time at SUN Behavioral.

If she were being honest with herself, it seemed like the psychiatric facility was doing more harm than good.

Many of the kids he was interacting with had mental issues much more severe than Fred’s. They had more significant behavioral problems, and even more problematic family lives.

But Dallas had no other choice — there was nowhere else for him to go, and it wasn’t safe for him to be at home.

She hadn’t known Fred to have drug issues in the past.

Rehab wasn’t what her son needed. But the program was 90 days. It was a far cry from the two-week stints he was doing at local psychiatric facilities whenever he was in crisis.

The hospital referred him to a program in Pasadena. A COVID outbreak sent him home early.

August 2020

Houston

Dylan answered his mom’s phone call, expecting another half hour spent bragging about his little brother.

She’d been calling a lot to gush about Fred — how he had graduated, how he had gotten a job, how he finally had his life on track.

But this call was different.

“He’s gone again,” Dallas said dejectedly. “He’s at your aunt’s house.”

Fred had gone to Missouri City after running away, hitching a ride with anyone who would take him.

His aunt had found him roaming around a grocery store and brought him home.

This was the best case scenario. Fred was with someone who loved him and would take care of him.

But over the next few months, Fred ran away from his aunt’s house multiple times.

He went to his uncle’s next, where they offered him as much freedom as possible — treated him as much like an adult as they could.

Within days, he’d left there, too.

November 2020

Alvin

Savannah Hypes’ phone started chiming nonstop, the familiar sound of her SnapChat notification drawing her away from her favorite TV show.

The messages were all from friends she made in rehab earlier that year. And they were all about Fred.

In various states of panic, her friends implored everyone to look for the smiling, happy kid who could never stop dancing. He had gone missing. He should not be alone.

Savannah sucked in a breath. She had just talked to Fred a few months ago.

Where could he have gone?

It was just one of many times Fred had run away from his aunt’s in the past months.

Savannah was 16 when she met Fred in rehab. Though boys and girls at the facility weren’t supposed to talk, they found their ways — meeting in shaded corners outside and leaving messages taped to desks or scrawled across bathroom walls.

She was immediately drawn to Fred because he was so different from everyone at the facility. Instead of despair, he had hope. Instead of being angry, he could never stop smiling.

Savannah closed SnapChat and opened Instagram, shakily typing in Fred’s handle. No recent posts.

She typed out a message.

“If you need anything, let me know.”

April 2021

Webster

Fred’s shirt was damp with sweat as he skated around the roller rink at FunCity Sk8, Asa on his heels as the neon lights pulsed around them.

The more laps they took, the more giggles Fred elicited.

For a brief moment, it was like old times, when Asa would take her little brother on dates every few weeks.

But when Asa and Fred sat down for ice cream at Baskin Robbins, they were rocked back to reality.

“Fred, you have to stop running away when you’re mad about something,” Asa said.

For the past eight months, Fred had been living on and off with his aunt in Texas City. He would be there for a few weeks, get mad about something silly and leave, just to come back a week later.

Fred kept digging into his scoop of chocolate.

“I understand you get frustrated,” she said. “Just come to my house. I’m not going to have a bedtime for you. I want you to just come here to decompress.”

She urged him to call her whenever he needed.

He said he would.

August 2021

West Oaks Hospital

Houston

Racial and homophobic slurs echoed through the halls of the 160-bed psychiatric facility in Houston — the majority directed at staff.

Amber Bush, 35, took it all in, flinching at every offensive word that fell out of the imposing patient’s mouth.

It was her first day at West Oaks. She had back surgery and had taken too many pills. She was not in a good place.

What have I gotten myself into?

Then, a small voice piped up — a voice nearly as small as the teenager it came from.

“Don’t say that!”

The slurs were then lobbed at him, a verbal assault that nearly escalated to violence before staff was able to sedate the offending patient.

By the time it was over, the teen was crying. Amber couldn’t help but think of her 19-year-old son — how scared he would be in a place like this.

“Hey buddy. It’s OK. What’s your name?”

“Fred,” he choked out.

Over the next four days, the two became inseparable, Fred showing Amber the ropes and Amber protecting him.

Fred was always smiling, always laughing — so much so that she started calling him Smiley.

But behind the happy facade, Fred was suffering. He told her his family didn’t want him — that he had no choice but to live in a homeless shelter.

Sometimes, he slept in the park. Sometimes, he had to eat food out of a dumpster.

He didn’t know what he would do once discharged: Individuals at the homeless shelter were threatening to kill him.

When Amber was released for another back surgery, the two vowed to keep in touch.

“Go back home, Fred. Your family loves you.”

September 2021

Hockley

Amber was laying in bed, recovering from two failed back surgeries and a lumbar fusion, when her phone pinged. Grimacing, she reached for it, a smile coming to her face when she saw it was Fred.

The two had remained in contact since their short time at West Oaks — they’d even gotten lunch once.

But the photo that popped up on her phone made her gasp. Fred — her sweet, silly Fred — was holding a knife to this throat.

“Wish I wasn’t here,” he wrote in the text.

“You’re better than this, Fred.”

Fred never responded.

Later that month in Stafford, Dallas answered an unknown number. The voice on the other end almost made her weep.

“Mom, it’s me.”

Months had passed since Dallas last heard from Fred. A friend told her that he had again checked himself into a local psychiatric hospital, likely using Medicaid. She couldn’t help but be proud.

This was evidence that she had raised him right. He knew he needed help and he had sought it out.

“Do you want help?” she said into the phone, holding back tears.

“I’m still trying to figure that out mom.”

She understood. She was ready to bring him home if he was ready to follow some ground rules.

She readjusted her 1 year old daughter, Saturn, in the crook of her arm.

“There’s another baby here,” she said. “You can’t steal. You can’t have people in the house — it’s not fair to everyone else.”

“I’m going to be scared,” she added.

Fred waited a beat before responding.

“I don’t want to make you scared mom,” Fred said. “I’m tired of disappointing you.”

Oct. 10, 2021

1201 Westheimer Road, across from Slick Willie’s in Montrose

4:14 p.m.

Cars dodged past Fred as he wandered down the middle of Westheimer Road, shirtless and clenching a 4-inch steak knife.

A Houston man, who wished to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation, was standing outside a nearby business where he works and chatting with friends. When he saw Fred, he did a double take.

What is he doing with that knife?

He’d seen Fred in the area for the past four or five months — just another lost kid, he thought, trying to find his way.

It was clear to the witness that Fred was mentally ill, but he seemed like a nice enough kid. They’d even chatted once before.

But the Fred he saw today was not the same teenager.

He had a vacant look in his eyes, like he was having a mental episode.

Though he didn’t appear threatening, the witness’ mind flashed through news story after news story about mentally ill people assaulting others without knowing what they were doing.

He ran into the building and locked the door.

Fred walked up to the glass door of the business and stared in at the witness and the other employees. Hand still clasping the knife, Fred meandered away.

The witness dialed 9-1-1.

“9-1-1 what’s your emergency?”

“There’s a man wandering around with a knife. I think he’s mentally ill.”

Over the police radio, a dispatcher told officers what to look for.

“Black pants with neon green stripes standing in the middle of the street.”

“Possibly has mental issues.”

They arrested Fred and charge him with aggravated assault with a deadly weapon.

SOUND ON: Listen to the 911 call leading to Fred's arrest near Slick Willie’s in Montrose. He is charged with aggravated assault with a deadly weapon. Video: Mark Mulligan/Houston Chronicle

Oct. 12, 2021

Harris County Courthouse

4:56 a.m.

The sun hadn’t even risen by the time Magistrate Diana Olvera, hearing officer for Harris County Criminal Courts, called Fred’s name.

His probable cause hearing, where an officer determines if it is reasonably believable that a crime has been committed, was supposed to happen at 10 p.m. the night before. He’d been pushed to 4 a.m. this morning.

But Fred’s slight frame and closely shorn hair could not be found amongst the six sleepy individuals sitting in the courtroom.

He was in the jail’s mental health unit. He wouldn’t be present today, Olvera said.

Two days earlier, Fred had been arrested in Montrose after multiple people called 9-1-1, reporting a man with a knife.

Dallas was relieved — it felt like she’d opened a Wonka chocolate bar and found a golden ticket.

In all the years she’d been trying to get Fred help, she’d been told over and over again that the best way to do that was for him to go to jail — a place where he would be evaluated for mental illness and officially labeled incompetent.

And the court had already ordered that Fred be interviewed to determine if he had a mental illness or developmental disability.

That morning, the state asked for a $75,000 bond, saying he presented a “current threat of physical violence.” Olvera was incredulous.

“I read this carefully: There’s no injuries, no stabbing,” she said. “The closest he got was 20 feet? The deadly weapon is a knife but …”

Noting his lack of criminal history, Olvera set Fred’s bond at $20,000 and moved on. The court appointed him an attorney, Kirk Oncken, later that day.

Fred remained in jail.

Oct. 27, 2021

Stafford

Dallas could hear Fred’s muffled voice in the background of a strategy call with his attorney. She knew her son well enough to catch the subtle notes of panic bubbling up at the end of his sentences.

“Mom, this is a scary place,” he said softly. “It feels like I’m in a bad dream.”

Dallas’ heart broke. Her baby boy — whom she had grown, whom she had nurtured, whom she had tried to keep safe — was terrified.

But she also knew this was the wake up call he probably needed.

Weeks earlier, she had called the jail to tell them he shouldn’t be in the general population because of his IQ. She dropped off his IEP paperwork from school. She thought steps had been taken to protect him.

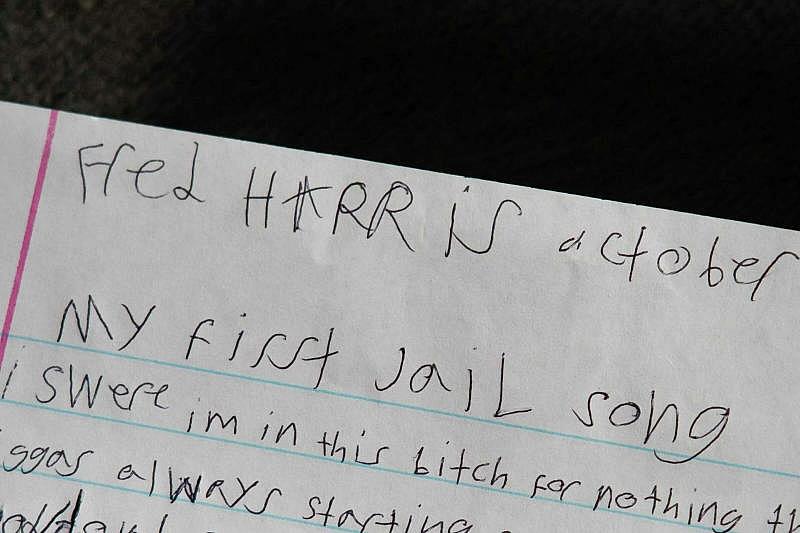

Sitting in Harris County Jail, Fred put pencil to paper and began to scratch out his feeling in song:

“I swere Im in this b*** for nothing these n***s always starting something i feel like god dont f**** love me I gess thats why he always judge me when I was locked up in da pin my n***s didint send me shit I swere I wanted to f**** cry god oh god why did you put me on this earth ben going through hell since birth/i/swere im depressed as f*** that’s why I shoot that sh** up”

Michael Paul Ownby, a 25-year-old Houston man with a history of violence, had just been convicted of continuous violence against the family.

While being escorted into a cell at the Harris County Jail, the 6-foot 2-inch 240-pound man struck a detention officer. He was charged with assault of a public servant.

The following day, the court ordered a psychiatric examination to determine Fred’s level of competency.

Among the belongings of her son, Fred Harris, that were returned to her from the Harris County Jail, Dallas Garcia found books, including a bible, and a rap that Harris had begun to compose before he was killed by another inmate. Mark Mulligan, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer

Oct. 29, 2021

Harris County Jail

10:40 p.m.

Fred and Ownby were in their shared cell at the Harris County Jail, having a late night chat.

What allegedly happened 36 minutes later was laid out by the district attorney’s office in a hearing:

Video surveillance shows Ownby walk over and begin wailing on Fred — first with his fist and, then, a shiv fashioned from a sharpened utensil.

Ownby had half a foot and 140 pounds on the 5-foot 8-inch, 98-pound Fred. Ownby struck Fred over and over in the face and neck. After the first few hits, Fred crumpled to the concrete floor of their cell.

Ownby threw the shiv across the room, grabbing Fred by the neck and, later, the shirt. He slammed Fred’s head into the concrete floor 10 times.

Blood pooled beneath Fred. He wasn’t moving.

But that didn’t stop Ownby, who started stomping Fred’s head with his left foot. He then picked Fred up and threw him at the cell door like a rag doll.

The 25-year-old alternated between slamming Fred’s head into the concrete, and stomping on his head over and over again.

When detention officers finally arrived and detained Ownby, Fred was unresponsive. They transported him to Ben Taub Hospital in Houston.

It was too late.

Epilogue

Jagger lay prone on the floor of Fred’s room sobbing, his brother’s size 9 flip flops tucked under the bed as if Fred had just returned home from school and climbed under the covers.

“Can Fred come home now?” he begged Dallas, his little voice cracking.

Tears sprang to Dallas’ eyes. She scooped Jagger up and carried him out of the room.

“I wish, baby. I would give anything.”

Fred’s room hasn’t changed since his death: The framed bible verse remains on his bedside table. The plant hanging in front of his window is still alive.

If Dallas closes her eyes, she can still picture him sitting there, playing video games and talking trash with Dylan through his headset.

The absence of her fearless, cheerful boy — the boy who danced in the kitchen; who never missed a family game night; who knew every Coldplay album by heart — is palpable.

She’s hired an attorney, hoping to get justice for her son. The lawsuit hasn’t been filed.

In a statement, the Harris County Sheriff’s Office said that Fred’s death is still under investigation by its Internal Affairs Division, its Office of Inspector General and the Texas Department of Safety’s Ranger Division. The findings of the internal review will be turned over to the office’s Administrative Disciplinary Committee for any policy or procedure infractions.

“These disciplinary measures could include, suspension and or termination of that employee (or employees),” the statement said.

The results of the Rangers’ investigation will be given to the Harris County District Attorney’s Office.

The last time Asa spoke to her brother before his death was their date night in April.

She still talks about Fred in the present tense, as if his voice was just one phone call away.

She can’t believe she’ll never again get to take him out for ice cream or sing at the top of their lungs while dancing their hearts out.

After Fred’s death, Dylan stopped eating. He couldn’t stop crying. He thinks back to all the times he didn’t drop everything and pick Fred up when he was roaming the streets in crisis.

Could I have saved him?

Dylan is currently planning his wedding. Fred was always supposed to be his best man — to hype the party up and get everyone dancing.

It will be a tough day, not having him there. But more than anything, Dylan is upset Fred will never have his own wedding. Never have his own kids. Never grow old with someone he loves.

Amber Bush was watching the nightly news in November when she saw Fred’s photo flash across the screen.

“Dallas Garcia is grieving the loss of her 19-year-old son, Fred Harris,” the news reporter said. “Authorities say he died after a fight on Friday ...”

Amber started to shake. The rest of the report was a blur as she hopped on Facebook to confirm the news.

She thought back to the countless times Fred told her he feared being killed by others living in the homeless shelter. She imagined that’s why he was carrying a knife on the day he was arrested.

Could I have prevented this? Should I have taken him more seriously?

The witness who called the cops when he saw Fred wandering around with a knife was at home scrolling through Reddit when he saw a headline about Fred’s death. He burst into tears.

What would have happened if I hadn’t called the cops that day?

Stafford High School is a campus within Stafford Municipal School District. Gracie Martinez, a spokeswoman for the district, said staff and students were “deeply saddened” by Fred’s death.

“In order to reach his academic goals, the district was able to provide him with both internal and external services, and this was done in partnership with the family,” she said in a statement. “Every child is different, and our staff works collaboratively with each student, their family and the community to provide services and supports that meets each child’s academic, behavioral, and social/emotional needs.”

Dallas said it wasn’t enough.

Experts recommend that districts have specific student to mental health professional ratios in order to serve students best. Those ratios are one per 250 students for both counselors and social workers, one psychologist per 500 students and one nurse per 750.

Stafford failed to meet those ratios every year that Fred attended high school.

Martinez said that the “district implements a staffing formula that is board-approved and commensurate with our student population.”

Harris County has a jail diversion center, where mentally ill individuals can be transferred instead of being jailed.

If police encounter someone with a mental health issue, they can call the District Attorney’s Office Intake Line. An official with the DA’s office — in collaboration with the officer involved — can determine that jail diversion is a good fit or decide to file charges.

The program typically is reserved for individuals accused of low-level, non-violent offenses. Fred was charged with a felony.

A Harris County hearing officer ordered that Fred be interviewed to determine if he had a mental illness or an intellectual disability the day after he was arrested. But a competency evaluation wasn’t ordered until the day before he was beaten, more than two weeks later.

Kirk Oncken, Fred’s appointed attorney, did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

All local mental health authorities and local behavioral health authorities — which contract with the Texas Health and Human Services Commission to provide mental health care statewide — offer transition-age youth services for kids who need support as they enter adulthood. Discussions about these services are recommended to begin around age 14, for those with “serious emotional disturbance.”

Between 2017 and 2021, 1,053 individuals participated in the program, which provides employment assistance and housing, for example.

Dallas had never heard of these services, she said.

Martinez said the Stafford school district provides all students age 13 and older with transition information.

Michael Paul Ownby has been charged with murder in Fred’s death. At his probable cause hearing in November, it took the state two-and-a-half minutes to describe the brutal attack on Fred.

Tributes to Dallas’ kids adorn her body: The planet Saturn etched into her finger for her baby daughter; ‘Jagger’ in red letters running down her right arm.

Fred and Dylan’s names are on her right shoulder. She placed Fred’s name on her left forearm, nestled into a music note-turned infinity sign.

She tries to stay strong for her youngest kids, but her life is now a string of reminders.

A stocking on the mantle that Fred will never again tear off the hook on Christmas morning.

A stack of books never cracked.

A pair of glasses gathering dust on a bookshelf.

Sometimes she can’t help but think:

How can I possibly survive this?

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts or depression you can call the Crisis of Intervention Houston Hotline at 832-416-1177.

Reporting

Alex Stuckey • alex.stuckey@chron.com • @alexdstuckey

Stephanie Lamm • stephanie.lamm@chron.com • @stephanierlamm

Visuals

Mark Mulligan • mark.mulligan@chron.com • @mrkmully

Editing

Mizanur Rahman • mizanur.rahman@chron.com • @Mizanur_TX

Copy editing

Charlie Crixell • charlie.crixell@chron.com • @ccrixell819

Design

Alexandra Kanik • alexandra.kanik@chron.com • @act_rational

Kirkland An • kirkland.an@chron.com • @kirkland_an

Ken Ellis • ken.ellis@chron.com • @kenduque

Jasmine Goldband • jasmine.goldband@chron.com • @fotojaz

Audience

Dana Burke • dana.burke@chron.com • @DanaPBurke

Jordan Ray-Hart • jordan.ray-hart@chron.com • @JordanLRay

Tommy Hamzik • tommy.hamzik@chron.com • @T_Hamzik

Laura Duclos • laura.duclos@chron.com • @LauraDuclosHC

John-Henry Perera • johnhenry.perera@chron.com • @pererajh

Data support

Christian McDonald • christian.mcdonald@utexas.edu • @crit

Executive Producer

[This story was originally published by the Houston Chronicle.]