Texas schools don't have enough mental health providers, and leaders are failing to fix it

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2021 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this project include:

PART 1: Texas schools don't have enough mental health providers, and leaders are failing to fix it

PART 2: ‘How did this happen to my son?’

EPILOGUE: How can schools provide mental health services for students? Here's one expert's recommendations.

Mark Mulligan, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer

ARLAND — Sitting at her desk, Luna Mestre-Colón felt her throat tighten.

She reached into her binder and pulled out a piece of paper with instructions for a breathing exercise, the edges creased from frequent use. The school counselor told her to follow these steps when she felt an anxiety attack coming.

This particular teacher at Garland High School hates it when Luna leaves class, but her anxiety attack can’t wait for the bell to ring. She needs to see the counselor now.

The teacher reluctantly excused the 10th-grader, but the counselor’s door was closed: He was busy with another student. Again.

Luna hid in the bathroom and waited for the panic to subside.

“It comes on at the weirdest times,” she said of her anxiety. “I have no idea why.”

Half of all mental illness begins by age 14, the American Psychiatric Association found. And the U.S. Department of Education highlights school counselors, social workers, nurses and psychologists as critical in identifying mental health concerns in children.

But at no point since 2013 did any Texas school district have the professionally recommended student-to-provider ratios in all four positions, a Houston Chronicle investigation found.

That means for nearly a decade, more than 5 million kids in Texas schools each year have gone without appropriate access to mental health professionals.

Addressing mental health needs in children has become increasingly important during the COVID-19 pandemic, as students like Luna were forced into isolation and stuck behind a computer screen.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that mental health-related ER visits increased 31 percent for kids ages 12 to 17 during the first year of the pandemic compared to the year prior.

Sen. Eddie Lucio, Jr., a Democrat from Brownsville who has filed several bills since 2015 to institute a counselor mandate, shook his head in disbelief when he heard that no school district in Texas has hit all four recommended ratios. He knows kids are falling through the cracks in the state’s education system.

"We need to make sure we seal those cracks to make sure we can save them," Lucio said.

A Chronicle analysis of staffing at all 1,200 public school and open-enrollment charter districts in Texas during the 2020-2021 school year found that:

- The vast majority – 98 percent – of students attended districts that did not meet the Texas Education Agency’s recommendation of one counselor per 250 students.

- The Texas Model for Comprehensive Counseling Programs, which schools must use to build their counseling program, sets a lower recommendation – one counselor per 350 students. Still, less than 3 percent of students attended districts that met that standard.

- The National Association of School Psychologists recommends one psychologist per 500 students. Just 25 districts met that standard.

- Only four districts met the 250 students per social worker standard recommended by the National Association of Social Workers.

- Two-thirds of districts failed to meet the ratio of one nurse per 750 students, as recommended by the National Association of School Nurses.

The Chronicle interviewed staff in 10 districts, from urban to suburban, large to small, across the state about mental health-related positions.

Most said the staffing shortage comes down to money.

The state does not provide districts funding specifically earmarked for hiring these four positions. Districts have to cobble together resources from federal, state and local revenue, as well as partnerships with philanthropic organizations.

“While the state provides recommendations for appropriate staffing ratios in a variety of areas, ultimately it is local school system leadership that decide to allocate funds for any given position,” the TEA said in a statement. “School systems have tended to prioritize teaching positions. With more teaching positions, less funds remain for other positions.”

The TEA added that community partnerships with organizations, such as faith-based counseling providers and telehealth mental health providers, should be taken into account when analyzing mental health staffing at school districts.

Alamo Heights ISD, a school district in San Antonio, serves nearly 5,000 children and has never met the recommended ratios for counselors, social workers, nurses or psychologists. In lieu of funding streams for these positions, it partners with community organizations to fill the gaps in service.

“Those ratios are not required by state law, and they are not directly supported by state funding, per se,” Frank Alfaro, the district's assistant superintendent for administrative services, said in a statement. “Funding is the biggest obstacle that most districts would have in approaching those ratios.”

Experts say a mandate for these positions in schools could help.

Oklahoma state law dictates that counseling programs in middle and high schools must have one counselor per 450 students in order to receive accreditation. In 2019, Arkansas passed a bill, sponsored by two Republicans, that requires one counselor per 450 students.

Texas is one of 28 states that do not have a mandated counselor-to-student ratio, despite numerous legislative pushes to do so since at least 2013.

Collecting data could spur the Legislature to make these changes, experts say, but movement on that has been recent.

Even with mandates of various strengths in other states, only three states met the counselor ratio, no states met the social worker ratio and just four states met the psychologist ratio, according to an ACLU analysis of the U.S. Department of Education’s 2015-2016 federal Civil Rights Data Collection.

Since 2020, the federal government has handed down billions of dollars of COVID relief funds to Texas school districts – some of which can be used for mental health support.

Despite ramped-up support for better access to mental health care in schools, especially after the shooting at Santa Fe High School in 2018, some are pushing back.

The Republican Party of Texas’ 2020 platform supports abolishing the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium, a collaboration of health-related higher education institutions created in 2019 to improve mental health care availability for kids and teens.

Matt Rinaldi, chairman of the Republican Party of Texas, said in a statement that the issue isn’t about access to mental health care but who determines whether services are needed.

“Parents want schools to return to teaching their children things like reading, math, and history; the more they expand to other areas, they either do it poorly or are overtly harmful,” Rinaldi said. “We believe the parents should decide if their child needs mental health services, not the schools. These bills are a thinly veiled state intrusion into Texans' personal decisions, parental rights, and sincerely held religious beliefs.”

The TEA requires school districts to get parental consent for specialized mental health services, with some exceptions.

Greg Hansch, executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Health Texas, is strongly against the GOP platform that would cut down some of the mental health resources that have recently been put in place.

“We’ve been behind the curve in providing early intervention efforts, and now people are trying to wind the clock back on services,” Hansch said.

Gathering the data

Long before Luna was holed up in the bathroom of Garland High School, bracing herself against the tile walls and wishing she had help, Texas was struggling to meet the mental health needs of its students.

In fact, the state has failed to meet the recommended student-to-counselor ratio in schools since at least 2000, according to a 2014 study conducted by the University of Texas at Austin’s Texas Education Research Center. As student enrollment grew by more than 860,000 between 2000 and 2011, the average ratio remained hovering between 430 and 440 students per counselor.

But in spring 2011, lawmakers cut $5.4 billion in public education funding in an attempt to right a projected budgetary shortfall. Districts put counselors on the chopping block to balance their budgets.

The ratio started to climb.

By 2013, there was an average of nearly 470 students per counselor, even as the Legislature mandated additional responsibilities for middle and high school counselors such as requiring parent, student and counselor meetings.

The TEA recommends one counselor for every 250 students, which is based on recommendations from the American School Counselor Association.

The Texas Model for Comprehensive School Counseling Programs stresses that “without adhering to recommended ratios, it is clear that larger school counselor student caseloads equal less individual attention for students.”

Lawmakers repeatedly tried to address the problem by filing bills that would mandate a counselor-to-student ratio. The measures repeatedly failed.

Efforts ramped up in 2018, however, after the back-to-back school shootings in Parkland, Fla., and Santa Fe. The governor held a series of roundtable discussions on school safety and the report released in its wake recommended hiring more school counselors.

During the following legislative session, Sen. Lucio brought forth a bill that would have required districts to initially hire one counselor for every 500 students.

The bill never even got a hearing.

Across the U.S., schools have struggled to collect accurate and comprehensive data on mental health needs in schools, according to a U.S. Department of Education report released in 2021.

Texas is making moves to change that. A mental health task force was created by 2019 state legislation to evaluate state-funded mental health services that are provided to students.

“The bill authorized … the Texas Education Agency to ask its school districts about outcome data,” said Annalee Gulley, presiding officer of the task force. “By asking school districts to produce outcome data for state-funded school-based mental health supports we finally got the ability to track what’s being done and where and whether it’s working.”

That same year, the governor signed a bill creating the Texas Child Mental Health Care Consortium – which the Texas GOP wants to dismantle – as well as the Safe and Supportive Schools Program, which requires school districts to create teams that conduct behavioral threat assessments to serve each of its campuses.

As required in the bill, TEA has already collected data on these teams via a survey for 2020-2021. The mandatory questions focus on whether the district has established its program and how many team members have been trained in behavioral threat assessment. The survey also asks for data about how many threats — concerning behavior or communication that indicates a student might harm themselves or others — were reported and how many were referred for interventions.

According to that data, 95 percent of the state’s 1,200 school districts had established their Safe and Supportive School Program Teams prior to September 2021. In 70 percent of those districts, more than half of each district’s team members had received behavioral threat assessment training.

About 37,000 threats were reported in schools across the state between Sept. 1, 2020 and Aug. 31, 2021, the data shows, and more than 14,300 were referred to monitoring and interventions after it was determined they posed a risk. About 2,300 were considered an emergency or eminent risk and referred to police and the superintendent, as well as referred for monitoring and interventions.

To get a sense of which Texas districts track their students' mental health needs, the Chronicle surveyed all 1,200 public school and open-enrollment charter districts.

Of the 613 districts that responded, 57 percent could account for, in some way, how many students were removed from school or referred out of school for mental health services during the 2020-2021 school year.

A number of districts that said they didn’t track this information noted that it wasn’t required under the state’s data collection system, known as the Public Education Information Management System or PEIMS.

But Frank Ward, TEA spokesman, said the agency is working on adding a new data element to PEIMS related to the Safe and Supportive Schools Program.

Though Texas still has not implemented a mandated counselor-to-student ratio for all schools, the governor signed a bill last year that requires counselors to spend just 20 percent of time doing non-counseling related duties. The bill allows for alternate requirements if a district’s staffing needs mean a counselor has to spend more than 20 percent of their time on those duties.

The TEA also has added more programs and resources to address mental health in schools.

Project AWARE Texas, for example, has trained thousands of teachers, school leaders and support staff in mental health first aid and suicide prevention.

The agency also is coordinating with the consortium on the Texas Child Health Access Through Telemedicine (TCHATT) program that provides tele-mental health services for at-risk kids in schools.

In 2021, the TEA launched the Texas School Mental Health website, which hosts information on state-funded initiatives and outside resources for families, students, educators, counselors and community partners.

The TEA’s website hosts a list of suicide prevention resources, including an online hour-long training for educators.

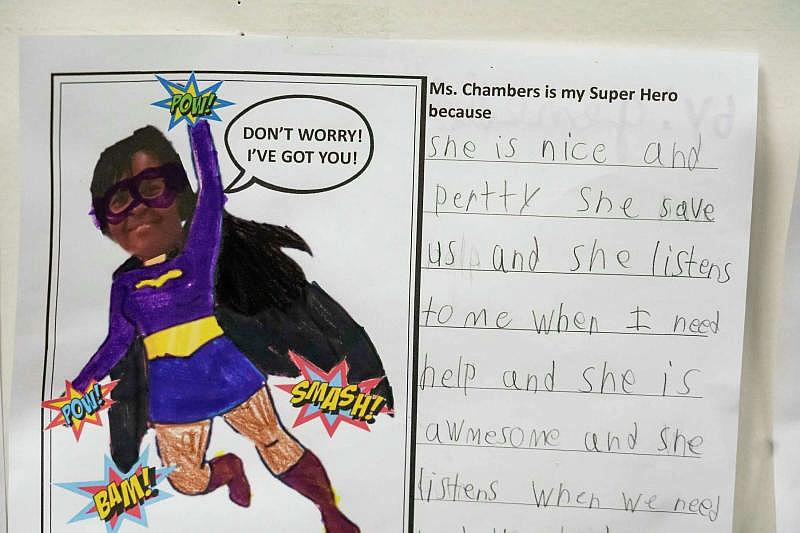

A note from a student hangs on the office wall of Hitchcock Primary School counselor Belinda Chambers. Mark Mulligan/Staff photographer A drawing made by a student is pinned on a wall in Stewart Elementary School counselor Melissa Arnold's office in Hitchcock. Mark Mulligan, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer

The resource gap

Luna and her mom, Angelique Colón, moved to the Dallas area from Puerto Rico about eight years ago.

Colón could see that Luna desperately missed her family. She seemed sad and, often, angry about the move – about leaving her friends and loved ones behind and starting over in a place she had never even visited.

But Colón was a single mom. She moved to Texas for a better-paying teaching position. She thought she was doing what was best.

“My mom did a good job hyping (Texas) up,” Luna said. “She was like, ‘There’s Six Flags!’ But it was hard because I used to hang out with my cousins daily, and now I don’t really get to see them.”

Because Luna was getting good grades and making friends, Colón thought her sadness was normal and even expected given the life change.

“There was a lot of bullying because I had a really heavy accent when I first moved here,” Luna recalled.

Her third-grade teacher switched her class schedule to keep her away from the bullies. Making friends didn’t come easy for Luna up until eighth grade, when she started to come out of her shell.

But then, right as she was about to enter Garland High School, COVID hit. Suddenly, she was spending all day alone in front of a computer screen.

She retreated back into herself.

Colón didn’t know what to do. She couldn’t stay at home with Luna every day. She surprised her with a Husky-mix puppy, Miyuki, to keep her company.

It helped, but not enough.

Then, a friend of Colón’s who was studying to be an educational diagnostician asked to conduct a practice assessment on Luna.

“Ya know, Luna is really bright and smart,” Colón’s friend said. “But the test shows she’s a little depressed. She has the indicators.”

Luna’s behavior started making more sense.

“Is there any way that I can get a counselor or go to therapy?” Luna asked her mom.

But Colón couldn’t afford health insurance. The out-of-pocket cost of therapy for her only daughter was completely out of reach.

Luna found herself among a growing number of children across the U.S. who need mental health care but struggle with access.

The Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago found in 2020 that 71 percent of the 1,000 parents surveyed nationwide said the pandemic had taken a toll on their kids’ mental health. And a national survey by the America’s Promise Alliance found that 30 percent of the 3,300 13- to-19-year-olds surveyed were unhappy and depressed more than usual.

Hitchcock ISD, which is in Galveston County and serves a population of 80 percent economically disadvantaged students, already had a dedicated counselor on each of its campuses before COVID-19 hit.

“Our students have a lot going on in their lives,” superintendent Travis Edwards said. “So we’ve decided, as a district, to place a very high priority on taking care of our students.”

Following the Santa Fe High School shooting in 2018, Hitchcock ISD received funds to hire additional mental health professionals. Hitchcock ISD used that money to create a position for a crisis counselor – Vickie Rabino.

It’s a job that doesn’t end with the school day. Rabino makes sure every emergency department, charity and social services agency in the area has her number.

Late one night, her phone rang. It was the police.

“One of your students is in distress and threatening suicide.”

Rabino rushed to the scene.

Following a mental health assessment by Rabino, the student was transported to a hospital for treatment.

If there isn’t an active crisis to attend to, Rabino spends her day coordinating partnerships with the local food bank, homelessness services, faith-based organizations and government services. She sees prevention as part of a holistic response to crisis intervention.

Having a counselor on each campus to manage day-to-day duties gives her the freedom to focus on long-term, creative solutions, Rabino said.

15Vickie Rabino, Hitchcock ISD crisis counselor, hugs a student as she walks through the high school in Hitchcock. Hitchcock ISD hired a full-time crisis counselor after the shooting at Santa Fe High School in 2018.Mark Mulligan, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer

“We have kids who are in crisis, who have family issues and stress from their home life. The goal is to take care of our students’ social and emotional needs because if that’s not in place, Algebra, English, whatever, are irrelevant,” Edwards said.

At the largest school district in Texas, Houston ISD, each counselor is responsible for 845 students.

HISD leaves the hiring of counselors up to each individual campus. Without a mandate from the state or the district, some campuses elected not to hire one at all.

But in February, the new superintendent of HISD, Millard House II, unveiled a five-year plan to get mental health resources to every campus.

In elementary schools with at least 250 students, the district plans to allocate one full-time counselor or social worker. In HISD middle schools, the district will allocate one counselor or social worker for every 350 students.

And in high school, the district will allocate a combined ratio of one per 450 students for counselors or social workers and college and career advisors.

“We already know there’s a gap,” Candice Castillo, executive officer of student support services at HISD, said. “It’s time to fix it.”

In Garland, Colón was trying to find her daughter help. She emailed the school counselor and asked if Luna could have regular one-on-one sessions, she said. The counselor responded that the school doesn’t provide those services, she added.

Colón wasn’t satisfied.

Garland ISD had 337 students per counselor during the 2020-2021 school year, one of the better student-to-counselor ratios in Texas.

At the high school, there were seven counselors to serve its nearly 2,400 students during that school year — a ratio of 338 students per counselor. There also are two responsive services counselors — one of which is at the high school on Monday and Thursday and the other Tuesday and Friday — who are licensed mental health professionals that provide short-term individual counseling, group counseling and crisis intervention, the district said in a statement.

All counselors make referrals to community agencies, including Counseling Institute of Texas, when necessary, the district said. Counseling Institute of Texas even provides counseling at a district facility, the statement said, and families can apply for grants offered through the institute. Those who don’t qualify are offered reduced rates.

Last week, the district's Board of Trustees approved a contract for telehealth behavioral and mental health services to all students free of charge.

As a school teacher, Colón knew that federal law requires public schools provide reasonable accommodations to students with disabilities, including depression.

One such accommodation is an Individualized Education Plan, designed for students with disabilities such as autism, deafness and speech or language impairment that need specialized help in school. That help can come in the form of occupational or speech therapy, for example.

Another is a 504 Plan, designed to accommodate kids with disabilities in a general education classroom. Those accommodations could look like getting extra time to take tests or using an audiobook version of a textbook.

Colón said school administrators recommended she look into a 504 Plan, which could allow for in-class modifications, like scheduled breaks, extended test time, reduced homework and excused lateness. But Luna already worked those issues out with her teachers on her own. The plan wouldn’t necessarily get her more time with a counselor.

Offered the choice between an outside referral or going the 504 Plan route, Colón took the referral.

The school connected them with a local clinic that offered 12 free therapy sessions funded by federal COVID-19 relief dollars.

Just as Luna had hoped, the therapist taught her how to manage her anxiety and helped her better communicate her feelings with her mom.

But the sessions soon ended. Colón filled out a survey, she said, and wrote that she and Luna wanted to do more.

No one ever responded, she said.

Sonya Wyche, a counselor at Lorraine Crosby Middle School in Hitchcock, holds two of the calming toys she provides students when they come into her office and are trying to calm down.

‘It was like putting out fires’

While the pandemic heightened the need for childhood mental health services in Texas, schools were strained for resources long before the virus took hold.

Rebecca Cole worked on Memorial Hermann’s Psychiatric Response Team for eight years, responding to calls from school districts when someone was threatening to harm themselves or others. But seeing students when it was already a crisis became exhausting.

In 2019, she took a job at her alma mater, Sealy ISD, as a part-time mental health professional, she said, a hybrid role encompassing the duties of a counselor, social worker and special education specialist.

Officially, her job was to provide therapy to students with one-on-one counseling mandated by their IEPs, she added. But in a district with no full-time social workers and only one full-time psychologist, she spent most of her days running across all four campuses.

“It was like putting out fires,” she said.

In a statement, Shawn Hiatt, executive director of human resources at Sealy ISD, said that Cole was brought on in a social worker role during the 2019-2020 school year and therefore “able to perform some of the duties of a counselor.”

“As for several districts, finding enough counselors and (Licensed Specialists in School Psychology) has had its challenges and hiring a social worker to fill in some of those gaps was important," Hiatt said.

The district had seven counselors for its 2,800 students, a ratio of about one to 400, during that school year.

Cole administered one-on-one and group therapy to students, she said, de-escalated dangerous student behaviors, screened new special education students, educated parents on how to promote positive behaviors at home and connected families with community resources.

Some students needed specialized therapy and medication — a higher level of care than she could provide at school, she added. Cole said she struggled to find providers to help, a problem not limited to the Sealy area.

The American Psychological Association found that only 4,000 of the more than 100,000 clinical psychologists in the U.S. serve children and adolescents.

Things can get trickier if a family doesn’t have insurance.

And Texas has the highest rate of uninsured children in the nation, with nearly 13 percent of children lacking insurance in 2019.

Local Mental Health Authorities, which contract with the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, can provide therapy to kids. But there can be a waitlist especially for those who need additional services.

Cole constantly struggled to find clinics that would accept children, that took insurance or offered discounted services, that had immediate availability and that weren’t an hour away in Houston.

Cole grew increasingly frustrated by her inability to help students. She quit after two semesters.

Anxiously waiting

Now that the free sessions have ended, Colón is struggling to find a therapist for her daughter.

She’s resigned herself to paying out of pocket for Luna’s care – but after calling at least a dozen providers and looking into teletherapy, she can’t find anyone who will accept teenagers.

And even if they do, there’s usually such a long waitlist that Luna wouldn’t be able to see a therapist for months.

The two find themselves relying on the school’s counselor for help.

When he’s available, he helps Luna manage her anxiety and feeling of overwhelming sadness as she sits in class or wanders the halls.

“He does a lot of breathing exercises and has us use stress relief toys,” she said. “He’ll sometimes turn on music or a movie to get us to relax. And then we talk through what happened and he gives advice for how to get through the rest of the day.”

But she often finds herself sitting on the floor outside waiting for him to finish with another student, or, adding her name to a long list of kids waiting for help so she can be called out of class at a later time.

Sometimes, she doesn’t bother doing either.

Colón knows when Luna can’t get in to see the counselor, her phone starts blowing up with text messages.

“Mom, please come get me.”

‘It takes reimagining the system’

Not all school-based mental health personnel fall into job categories collected by the TEA.

Data collected by the state showed that Frisco ISD had no social workers on staff last year. Instead, the district hired 10 “school support specialists,” nine of whom are licensed social workers.

The support specialists connect students with government programs and charities, work with county social workers and help families find outside counseling services.

“I’m not calling them social workers, or requiring that licensure, because we didn’t want to limit ourselves in hiring in case we found other people that were qualified,” Stephanie Cook, managing director of guidance and counseling services at Frisco ISD, said.

Avoiding the social worker classification also allows the district to set the pay for support specialists in line with the teacher salary scale. Funding for the positions came from a federal COVID-19 relief program for elementary and secondary schools.

In the first six months of the program, the school support specialists handled nearly 1,500 referrals from school counselors.

Frisco ISD also has two hospital liaisons who manage students undergoing hospitalization for mental health crises and 11 student support specialists who provide crisis intervention services to students and families.

Those positions aren’t classified as mental health providers in the TEA’s data.

Along with about 140 counselors on staff, the district works with local counseling agencies to provide additional therapy options for students. That partnership isn’t tracked by the TEA, though the agency said in a statement it was exploring ways to add more mental health data elements to PEIMS.

Without a mandate – and funding that might come with it – districts like Frisco rely on community partnerships and creative hires to meet the needs of students.

“I think it takes reimagining the system,” Cook said.

Luna wants to try managing her depression and anxiety with medication. Without regular access to a therapist, she hopes medicine can stabilize her mood swings and prevent depressive episodes.

In order to prescribe medication, her pediatrician would need to conduct an assessment. That appointment would cost $200 out-of-pocket, Colón said.

This summer, during their annual trip to Puerto Rico, Colón plans to take Luna to a specialist to get started on medication. She expects to pay about half of what she would in Texas.

In the meantime, Luna has found ways to cope. She’s teaching herself guitar. She experiments with makeup. She takes care of her dog, Miyuki, and the many stray cats in her apartment complex.

“I watch horror movies,” she said with a snicker.

The jump scares on screen make her forget about her real-life worries -- but just for a moment.

When she gets overwhelmed, she remembers what her counselor taught her.

She closes her eyes and takes a deep breath.

Luna Mestre-Colón, 15, posed with her mother, Angelique, outside their home in Garland in March. Luna attends Garland High School and has struggled to get time with the school counselor when she has an anxiety attack. The two have been trying to get Luna help for her depression and anxiety for years.

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts or depression you can call the Crisis of Intervention Houston Hotline at 832-416-1177.

Reporting

Alex Stuckey • alex.stuckey@chron.com • @alexdstuckey

Stephanie Lamm • stephanie.lamm@chron.com • @stephanierlamm

Visuals

Mark Mulligan • mark.mulligan@chron.com • @mrkmully

Editing

Mizanur Rahman • mizanur.rahman@chron.com • @Mizanur_TX

Copy editing

Charlie Crixell • charlie.crixell@chron.com • @ccrixell819

Design

Alexandra Kanik • alexandra.kanik@chron.com • @act_rational

Kirkland An • kirkland.an@chron.com • @kirkland_an

Ken Ellis • ken.ellis@chron.com • @kenduque

Jasmine Goldband • jasmine.goldband@chron.com • @fotojaz

Audience

Dana Burke • dana.burke@chron.com • @DanaPBurke

Jordan Ray-Hart • jordan.ray-hart@chron.com • @JordanLRay

Tommy Hamzik • tommy.hamzik@chron.com • @T_Hamzik

Laura Duclos • laura.duclos@chron.com • @LauraDuclosHC

John-Henry Perera • johnhenry.perera@chron.com • @pererajh

Data support

Christian McDonald • christian.mcdonald@utexas.edu • @crit

Executive Producer

[This story was originally published by the Houston Chronicle.]