How reporters everywhere can cover the big ACA lawsuit now

A Texas lawsuit once viewed as frivolous could now pose a real threat to the Affordable Care Act, impacting consumers, the health insurance marketplaces and even the mid-term elections.

“It’s unclear how strong the risk is, but the threat is real,” said Stephanie Armour, health policy reporter for The Wall Street Journal.

Armour and leading health policy expert Timothy Jost, emeritus professor of law at Washington and Lee University School of Law, discussed whether the ACA can survive this latest legal maneuver, the possible implications for Americans and how reporters can cover the story in a Center for Health Journalism webinar this week. Even if the health law survives, the legal threat could impact the midterm elections and add new uncertainty to already fragile health exchange markets.

What’s at stake

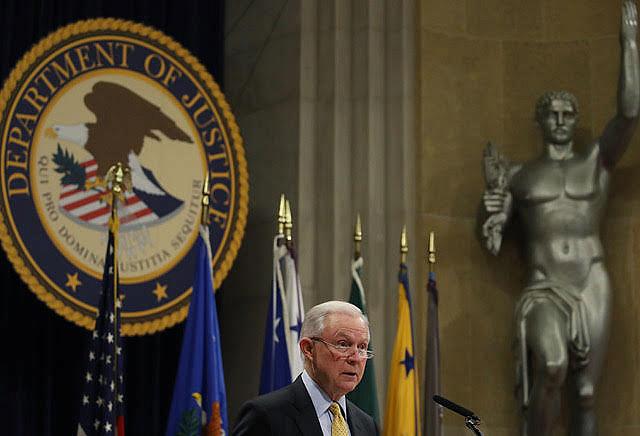

The suit, which was brought by 20 Republican-led state attorneys general in February, argues that the health law’s individual mandate is unconstitutional after the GOP 2017 tax bill eliminated the associated penalty for those without insurance. Since the rest of the ACA depends on the mandate, they argue, it should be thrown out, too. The bombshell, though, came on June 7 when the Trump administration said it wouldn’t defend key provisions of the Affordable Care Act against suit, including the law’s protection for patients with preexisting medical conditions. The Department of Justice brief argued that the law’s core consumer protections can’t be separated from the mandate.

If Judge Reed O’Connor agrees, millions of Americans with pre-existing conditions could eventually face insurance coverage denials or higher premiums. A win for Texas would be appealed to the United States Court of Appeals for the conservative-leaning Fifth Circuit, and ultimately, the Supreme Court.

A decision in favor of Texas this summer wouldn’t likely have many immediate practical effects, other than adding to consumer confusion and anxiety, Jost said. Insurers would likely stay the course in the short term, though the uncertainty could drive some out of the marketplaces altogether.

“I think this is something that affects every reader, listener or viewer of every reporter on the line.” — Timothy Jost

Still, the decision could ultimately have ripple effects that go well beyond preexisting conditions. If high-risk individuals can’t find or afford insurance coverage, hospitals and providers could face higher uncompensated care costs. And, if insurers are allowed to customize premiums based on an individual’s health risk, calculating premium tax credits for qualified people becomes tricky. Right now, for example, the credits are based on the second-lowest cost silver plan.

Ultimately, Jost suspects the real agenda behind the Texas lawsuit is to drive another Obamacare repeal effort in Congress, after the GOP’s plans collapsed last year.

Opposition to the lawsuit is mounting. Last week, about a dozen amicus briefs were filed in defense of the ACA, from insurers and providers to small business groups — an ideologically diverse group that makes apparent how deeply entrenched the health law has become, Jost said.

“Support is now almost universal across our health care system by people who are really affected by the ACA,” he said.

Removing the protections against pre-existing conditions would not only affect people on marketplace plans, but also those with employer-based insurance, since it could discourage them from leaving their jobs. And employer plans could lose other protections. As Armour reported last week: “If the courts toss some ACA provisions linked to the insurance-coverage mandate, elements of the requirements that also apply to employer plans would likely be halted or reversed as well, analysts said.”

“I think this is something that affects every reader, listener or viewer of every reporter on the line,” Jost said.

Covering the story

WSJ’s Armour said the administration’s recent decision not to defend the ACA caught many reporters off guard. Armour was coming home from an evening going-away party for a colleague when the news broke, while another reporter she knows dashed into a coffee shop still wet from swimming to cover the unexpected news.

“It really ratcheted up interest in health care again, beyond even just this legal case,” she said.

That interest extends to politics, where the move could influence the upcoming midterm elections. The suit could be a Democratic bonanza, giving them “ammunition to portray Republicans as out to steal health care,” she said.

It could also lead more Democrats to go even farther than efforts to fix the ACA, with some pushing for “Medicare for All” as a stepping stone to a single-payer system. Reporters should keep in mind there’s a rift in the Republican party between the moderates who want to move on from health care and conservatives eager for another go at repeal, Armour said.

There are myriad ways reporters can localize this story, Armour explained. For one, call insurance companies who offer exchange plans and ask whether they’re preparing alternative rates yet. How much does this legal uncertainty factor into their decision to participate in marketplace plans? Reporters can also ask if patients are concerned about changes to the health law, and whether people are speeding up medical treatments as a result.

On the legislative side, reporters could also see if their states are planning their own legislation to protect people with pre-existing conditions if the federal law falls. And how is your state’s attorney support or lack of support for this Obamacare lawsuit playing out in campaign races?

“These tensions are there playing out now, and, frankly, I think they’re only going to escalate,” Armour said. “This is really an issue that you can explore in your state no matter what.”

**