Stereotypes of America’s poor explain why some states refuse to expand Medicaid

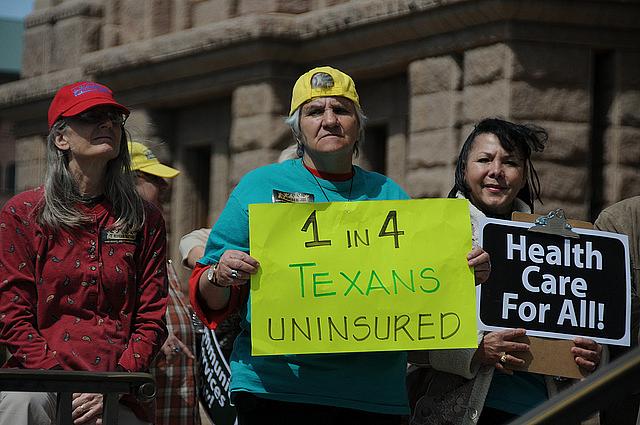

Advocates for expanding Medicaid face an uphill battle in states were poverty is largely seen as a personal failing.

Last week the Senate succeeded in passing legislation that essentially guts the Affordable Care Act and wipes out Medicaid expansion. While the president is expected to veto the bill, the Senate’s action shows that the program could be in danger come the next administration. The anticipated expansion has not occurred in 20 states, which have deprived some of the poorest Americans of health care. Recall that the Affordable Care Act envisioned that Americans with incomes below the poverty line would not be eligible for subsidies in the state shopping exchanges because states would instead provide Medicaid benefits, with federal dollars paying most of the tab. When the Supreme Court declared in 2012 that states didn’t have to provide the coverage, half refused, and ever since those for and against Medicaid expansion have been locked in a battle royal.

Eduardo Porter’s recent New York Times column got me thinking about Medicaid, legislators’ antipathy to the program, and why.

Porter argues that election rhetoric has so far swirled around helping the middle class while “ignoring the Americans who need their attention the most: the deeply, persistent poor.” Grim numbers framed his argument. One in 20 Americans or about 16 million people have incomes below 50 percent of the poverty line — living on about $8.60 per person per day for a family a four. Even more startling is the news that this group of poor Americans has grown by six million over the last 50 years. “No other advanced nation tolerates this depth of deprivation,” Porter wrote.

Porter presented some of the latest thinking on poverty by citing work in a new journal from the Russell Sage Foundation, one of the nation’s preeminent institutions studying social policy. The journal explains how American antipoverty strategy, which is focused on choosing between the “worthy” and “unworthy” poor, is actually shaped by our own ignorance of how those at the bottom struggle and live each day. It “exposes the inadequacy of viewing poverty as personal failure and the limitations of relying so heavily on providing low-income working Americans with a tax break to encourage better behavior, get a job and just stop being poor,” Porter wrote.

Porter gave a brief nod to Medicaid, arguing that states have not expanded because the deeply poor have no political organization to fight for them. Perhaps. But the lens of personal failure and our collective ignorance of what it’s like to struggle on $8.60 a day goes further to explain why states have not covered the very poorest, probably won’t in the foreseeable future, and why Medicaid as we know it could disappear.

It’s a compelling argument that has been woven into the context of this year’s media stories about why the hold-out states wouldn’t listen to arguments in favor of expansion — that expanding coverage was good for business; that the federal government was paying most of bill; that hospitals would benefit from less uncompensated care; that poor people could get medical care and better health; that disenfranchising them from the health care system was morally unjust. Tony Garr, a grassroots activist in Tennessee, observed that no matter how reasonable those arguments sounded, legislators didn’t listen to them. “Their minds were made up,” he told me. In Tennessee, it should be noted, a huge grassroots effort did organize on their behalf.

The lens of personal failure and our collective ignorance of what it’s like to struggle on $8.60 a day goes further to explain why states have not covered the very poorest, probably won’t in the foreseeable future, and why Medicaid as we know it could disappear.

In Kansas, the “deserving poor” strategy was evident in the remarks of state Sen. Dan Hawkins, the chair of a key legislative committee, who told the Kansas Health Institute he was opposed to providing taxpayer-funded coverage to non-disabled adults even if they can’t afford private insurance. “I always tried to find a job that had health care,” he said, when he was asked what poor Kansans needing coverage should do. “I’ve always worked, and I’ve always had a job that paid for health care or paid a portion of it.” In other words, these people can do the same. Never mind most do work but in low paying jobs that don’t offer health coverage, typically in restaurants, tourism, construction, and seasonal industries.

When Kansas finally killed off expansion in October, it was there, too, in an email to supporters of Gov. Sam Brownback from a press aide claiming expansion would have created “new entitlements for able-bodied adults without dependents, prioritizing those who choose not to work before intellectually, developmentally and physically disabled, the frail and elderly, and those struggling with mental health issues.” As a result, Brownback says the state will not expand Medicaid until disabled people already on Medicaid are thrown off the waiting lists for home care services. In other words, the state won’t give them too much help.

The “deserving” poor strategy was there, too, in neighboring Nebraska, where lawmakers have failed three times to bring health care to 77,000 people with the very lowest incomes. One state analyst told me many legislators believe those needing Medicaid are “lazy bums sitting around eating Cheetos and don’t want to work,” a sentiment echoed by state Sen. Kathy Campbell who has championed this issue for years. Once you get past the dislike of Obama, she told me, this stereotype is “in the back of the discussion. If you’re poor, you haven’t tried hard enough.” Some of the resistance, she said, also comes from lack of understanding of what it’s like to be poor, the same point Porter made in his column. “These people make decisions differently because they live from day to day and from week to week,” Campbell said. “We choose not to see them.”

It’s also much harder to move beyond the stereotype when ideologically-driven news outlets like Townhall.com tell audiences that “more than a third of those in the new expanded class have criminal records,” an assertion made without any back-up or attribution. Now who would want to give health care to an ex-con?

The strategy of helping only the “deserving” poor is a powerful rationale that undergirds the approach to Medicaid expansion taken by the handful of states that have imposed more stringent requirements on new recipients, mostly in the form of higher premiums and copays. It explains why Michigan recipients must make payments into a health savings account, with “richer” recipients — those with incomes between 100 and 138 percent of the poverty level — required to contribute 2 percent of their income in the form of monthly premium contributions. It also explains why the state is seeking federal permission to jack up the amount of cost sharing from 5 percent, the federal statutory limit, to 7 percent of their income for those who stay in regular Medicaid instead of joining a private plan. It explains why recipients with incomes between 101 and 138 percent of the poverty level in Indiana are locked out of coverage for six months if they don’t pay their premiums. And those below the poverty level? They’ll just get fewer benefits as a result. A few states have tried to impose work requirements. The new governor of South Dakota recently indicated he was considering doing that. So far, though, the Obama administration has said no.

And it explains why Kentucky may soon scrap its successful Medicaid expansion program that has brought coverage to 425,000 people. According to newly elected Gov. Matt Bevin, who is no fan of health insurance expansion, Kentuckians who got benefits under expansion don’t exercise enough personal responsibility. In Bevin’s book, that means making them contribute to the cost of coverage and changing the rules so fewer will get it at all. However onerous these changes may be for real people, “personal responsibility” sounds good and evokes the image of lazy poor people sitting around eating Cheetos and getting something they don’t deserve.

Stereotypes die hard, if they ever die at all.

Veteran health care journalist Trudy Lieberman is Contributing Editor of the Center for Health Journalism Digital. This is her second post for the recently relaunched Remaking Health Care blog series.

[Photo by TexasImpact via Flickr.]