Babies born early, ill, or dead: Florida spends millions on prevention. Why isn’t it getting better?

The story was originally published by the South Florida Sun Sentinel with support from our 2023 Data Fellowship.

Rebekah Antoine, 33, of North Miami Beach, attends a prenatal visit at the Southern Birth Justice Network in Miami in February. Antoine, who was pregnant with her fourth child, has since given birth to a healthy baby boy.

(Carline Jean/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

This is the third in a series of articles exploring maternal health care.

When she gets the call, Jennifer Clayton arrives with tissues.

She puts her hand on the shoulder of a grieving mother and guides her through the agonizing aftershock of losing a baby born too early, too small, or too fragile to make it to a first birthday. As the tears flow, she helps a mother choose a tiny outfit for her newborn’s burial, make funeral arrangements in a cemetery’s baby garden, and find a therapist.

Calling herself a bereavement doula, Clayton saw the need as a former labor and delivery nurse in Jacksonville who witnessed mothers holding their lifeless newborns.

“What’s happening breaks my heart,” Clayton said.

Each day in Florida, four babies die before they ever celebrate their first birthday.

Florida spent more than $170 million in 2023 to address maternal and infant health, about twice what it invested to bring more visitors to Florida, but less than it doled out for wastewater grants. Still, the high rates of infant and fetal mortality, preterm and low-weight births haven’t budged much since spiking and then plateauing a decade ago.

In 2022, just as in 2012, six out of every 1,000 babies born in Florida died before their first birthday.

The survival rate is worse for Florida’s Black babies, who die during their first year of birth more than two-and-a-half times as often as non-Hispanic white and Hispanic infants, Department of Health records show.

“I don’t think legislators are aggressive enough or give enough attention to Black maternal and infant health,” said state Sen. Rosalind Osgood, who sits on the Florida Senate’s Health Policy Committee. “We cannot be OK with so many Black women and so many Black babies dying.”

With the lives of America’s future generations at risk, federal health officials call infant mortality “one of the most critical and costly public health challenges in the U.S.”

Florida health professionals want the state to respond to the crisis as it would any public health emergency: redirecting money, approving policies to get women the care they need, and measuring results to better target state funds.

Florida’s lawmakers have funded outreach programs, mandated hospital maternity units participate in quality-control programs, launched a telehealth initiative to reach women in rural areas, and set a goal to reduce Black infant mortality by 2026. In addition, Florida’s newly approved Live Healthy legislation includes three measures aimed at improving birth outcomes: increase Medicaid reimbursement rates for hospital labor and delivery, allow cesarean sections at birthing centers, and ease restrictions on independent midwives.

Still, critics say the money Florida spends on maternal and infant health doesn’t reach far enough to keep more babies alive. They think the state should shift spending in key areas to improve birth outcomes: adjust the insurance structure to increase prenatal care; invest more in communities with the poorest birth outcomes; measure results to ensure accountability; and educate healthcare providers on how they can deliver higher quality, more racially sensitive care.

“Infant mortality is a serious issue facing the United States,” said Weesam Khoury, deputy chief of staff for the Florida Department of Health. “This is precisely why Florida has prioritized maternal health and the reduction of infant mortality for over a decade while implementing evidence-based initiatives to support our communities.”

Those initiatives aren’t having enough of an impact when so many Black babies and mothers are dying, said Jennie Joseph, founder of Commonsense Childbirth in Orlando and a national advocate for maternal health.

“What we have got is the continual spending of money in the same place, in the same cycles, doing the same research, and coming up with the same solutions as if that’s making a difference, and it’s not,” Joseph said.

On May 1, Florida banned abortions after six weeks, and maternal health experts fear infant death rates could worsen. In Texas, where abortion restrictions are among the strictest in the country, the state saw a spike in infant mortality in 2022 after a six-week ban went into effect in 2021, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services data.

“With more unintended pregnancies being carried to term and nonviable pregnancies being forced to continue …those babies will be carried to birth and die soon after,” said Dr. Tracey Wilkinson, an assistant professor of pediatrics and obstetrics at Indiana University College of Medicine. “They will contribute to the infant mortality rate rising even higher.”

Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz speaks at a Black Maternal Health forum at the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Community Center in Hollywood on April 6, 2024. The congresswoman said she will push for a national law called The Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act, which addresses 13 different measures that drive the maternal and infant health crisis and includes funding for diversifying the birth workforce.

(Mike Stocker/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

U.S. Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz gathered Black women, doctors, midwives and doulas on April 6 at a Hollywood community center to highlight National Black Maternal and Infant Health Week. The congresswoman said she will push for a national law called The Black Maternal Health Momnibus Act, which addresses 13 different measures that drive the maternal and infant health crisis and includes funding for diversifying the birth workforce.

Wasserman Schultz urged innovative and strategic investments on the state and local levels, too.

“We must own up to this grim reality, redouble our efforts to quickly remedy it and champion every solution available to reverse it or to overcome it,” she told the audience.

To understand why Florida’s fetal and infant mortality rates remain stubbornly higher than the national average and learn how resources could be better directed to keep more babies alive, the South Florida Sun Sentinel examined the state’s spending on infant health through state and federal health records, budgets, vital statistics and grant applications, as well as conducted interviews with more than four dozen women and families, community advocates, nonprofit leaders, health providers, researchers and state health officials.

What Florida is doing to keep babies alive

Linda Cichon remembers feeling numb as she held her lifeless son against her hospital gown. The previous night, she had felt him kick inside her. But that day, she felt no movement. A sonogram confirmed her worst fear. No heartbeat.

Now, after induced labor in a hospital in Plantation, she had birthed the baby she had longed for, yet he had never taken a single breath. “He had beautiful dark hair like mine. I still have a lock of it,” she said.

Shortly after leaving the hospital, she received more devastating news.

“An autopsy showed gestational diabetes, which could have been prevented, but I had not been monitored for it,” she said.

Jamarah Amani, founder of South Birth Justice Network, left; Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz; Sandra Elidor, an infertility advocate; Dr. Stevenson Chery, medical director of BCOM clinic; and Esther McCant, CEO of Metro Mommy Agency, gathered for a Black Maternal Health forum at the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Community Center in Hollywood on April 6, 2024. The forum helped raise awareness to reduce maternal deaths among Black women, a group three times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related factor.

(Mike Stocker/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

Decades ago, Florida lawmakers recognized a problem with babies dying late into pregnancy and before their first birthdays. In the 1990s they created programs to connect mothers with resources and study infant deaths. After the infant mortality rate soared to 7.5 babies dying for every 1,000 births, the state saw some improvement in the early 2000s from its new initiatives. Florida’s Department of Health told the South Florida Sun Sentinel that preliminary 2023 data shows a drop to 5.9, but experts consider that an insignificant change. The rate has fluctuated by a tenth of a percent over or under 6 deaths per 1,000 births each year over the past decade.

The plateau in infant mortality exists even as the state’s birth rate declined 10% over the past decade and the Black birth rate declined by 18%.

The state’s model for addressing infant health is a patchwork of programs with providers who often don’t share information or resources, and a reliance on supplemental local partnerships that exclude some Florida rural regions and impoverished communities, according to community leaders and health professionals. The inconsistency in spending, innovation and accountability exacerbates the large racial and geographic disparities in rates of fetal and infant deaths, and preterm births, they say.

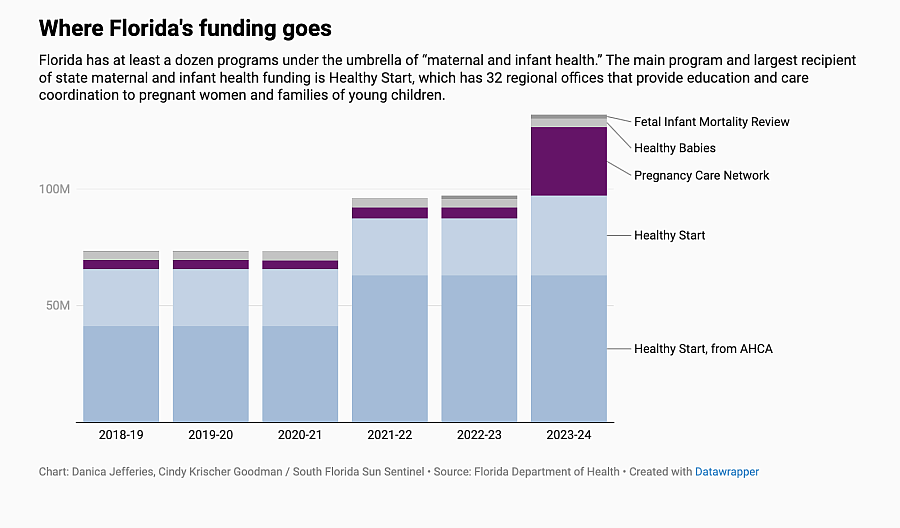

State money for maternal and infant health comes from general revenue and federal grants. Spending is directed toward initiatives such as newborn screenings, safe sleep education, early intervention services for developmentally delayed infants and a stillbirth prevention program. Florida has at least a dozen programs under the umbrella of “maternal and infant health.” The 2023-24 budget allocated $170 million to maternal and infant health programs, up from about $150 million the year before.

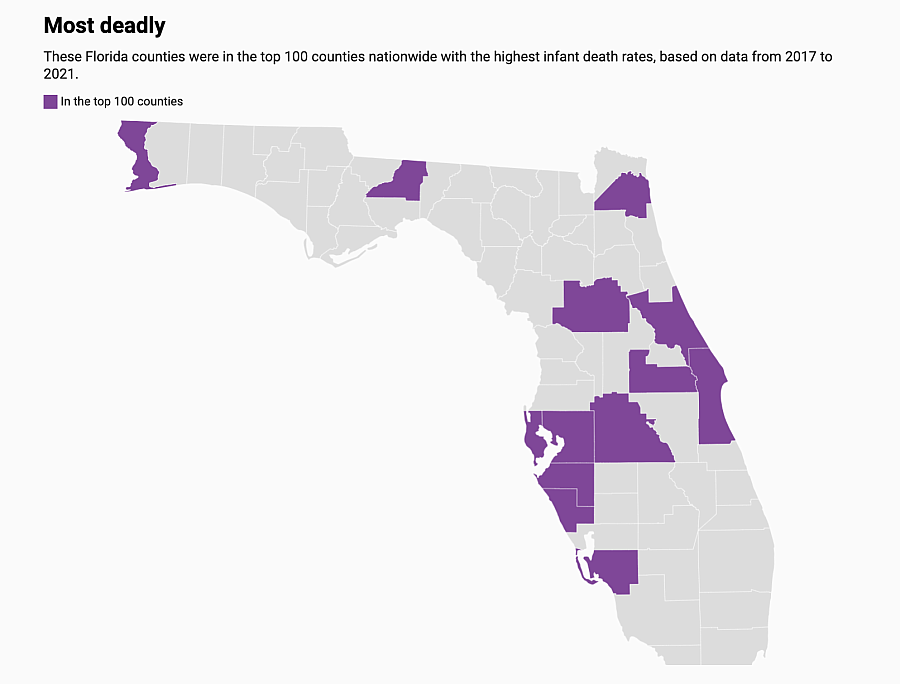

Even with the current levels of spending, Black babies are dying at high rates. Between 2019 and 2021, Black babies in half of Florida’s 67 counties had infant death rates three times as high as the state average of 5.9, according to data available from the Florida Department of Health.

Losing infants in their first year of life, particularly Black infants, is not just a health crisis in Florida. Nationally, in 2022, infant mortality was highest among babies born to Black mothers. Florida has dozens of counties and ZIP codes with high rates of poverty, uninsured families and chronic diseases like obesity that contribute to the widening the gap between Black and white infant mortality.

The state has set a goal to reduce the Black infant mortality rate from 10.7 per 1,000 live births in 2020 to 9.6 per 1,000 live births by 2026. In 2022, though, the rate worsened, climbing to 11.2. Khoury, at the Florida Department of Health, says provisional 2023 data reflects the rate declined to 9.3 in 2023.

“We will keep working until it is zero,” she said.

Florida’s main program and largest recipient of maternal and infant health funding — more than $100 million — is Healthy Start, a national initiative that came to the state in 1991. It currently has a network of 32 regional offices that provide education and care coordination to pregnant women and families of young children. Florida law requires healthcare providers to offer a prenatal risk screening to a woman at a first or second prenatal visit. For those parents who agree to voluntary screening, the Healthy Start program connects them to community resources if needed, or may enroll them in a home-visiting program. The Healthy Start Coalition’s specified mission is to prevent infant death and improve birth outcomes.

Cathy Timuta, CEO of the Florida Association of Healthy Start Coalitions, says her reports show infant mortality rates are lower for women who entered the Healthy Start program early in their pregnancy and received at least six home visits.

But state funding for Healthy Start hasn’t kept up with the need, and the screening process for referrals has relied on paper forms, with obstetricians filling them out and Healthy Start workers picking them up from medical offices and then manually entering patient information into their system. The process creates long lag times and delays in getting pregnant women resources that can help them through pregnancy. A move to electronic medical records is planned.

Florida’s Healthy Start program helps women on Medicaid as well as those who don’t qualify. The program went 17 years without a funding increase for services for non-Medicaid eligible families. Last year, Healthy Start appealed to the Florida Legislature for an additional $19.2 million from the Department of Health, saying the need had outstripped its funding.

“We needed to increase the number of staff,” Timuta told the South Florida Sun Sentinel. “Our caseloads on the front lines were way too high to make an impact on birth outcomes. The population had grown, the need had grown, and the funding hadn’t. We were just getting to a point where it just was too difficult.”

The organization received half of the amount requested from the state in 2023 — only $9.5 million.

An infant peers out of a carrying sling during the baby fashion event at the Community Birth Wellness Festival & Midwife360 Family Reunion in April at Dreher Park in West Palm Beach. The event brought together families, midwives, doulas, and healthcare providers for workshops, and demonstrations on natural childbirth, breastfeeding, postpartum care, and holistic health.

(Scott Luxor/Contributor)

That same year, another recipient received an increase of nearly triple that amount from the state budget — the Florida Pregnancy Care Network. That nonprofit organization comprises 95 alternatives-to-abortion clinics around the state that provide counseling “with the goal of childbirth” as well as pregnancy tests, pregnancy loss counseling, ultrasounds and parenting classes. These centers are not affiliated with medical practices but often with religious organizations, staffed by volunteers, and don’t have to be licensed or inspected in Florida to operate. They’re also not subject to HIPAA, the federal patient privacy law.

The network had been receiving state funds since 2010 and saw its first major increase in 2016, when lawmakers increased funding from $2 million to $4 million a year. In 2023, the network received a fivefold increase of $25 million, bumping its annual allocation to about $30 million. As a nonprofit, the Pregnancy Support Network is not required to detail how it spends the state money.

Florida Senate Democratic leader Lauren Book filed a bill in October to require pregnancy centers to provide information that is medically accurate (with fines for those that fail to comply), and to require the state Department of Health to complete annual financial and compliance audits. The bill did not advance, but the state Legislature did require the Florida Pregnancy Care Network to report annually to the Department of Health on the amount and types of services provided; the expenditures for the services; and demographic information for women, parents, and families served by the network. It also requires services be provided “in a noncoercive manner and may not include any religious content.”

The first report is due to the governor by July 1.

Rita Gagliano, executive director of the Florida Pregnancy Care Network, told the South Florida Sun Sentinel her organization has used the increase in funds to fill gaps in access to reproductive care throughout Florida.

While Planned Parenthood calls these centers “dangerous” for the type of medical information they provide, Gagliano said her network plays an important role in lowering infant mortality.

“We believe all of these services — from the critical wellness services and prenatal, postnatal, and parenting education and training to the centers who are helping bridge gaps in medical services in communities — help in the effort to reduce infant mortality and preterm births,” she wrote in an email.

Yet, Florida’s Healthy Babies Initiative, a state program created in 2016 and overseen by county health departments to specifically improve birth outcomes, gets only a fraction of the state money that is allotted to the Pregnancy Support Network. Healthy Babies receives state funding of only $3.7 million a year distributed among all 67 county health departments. The program provides classes, training and workshops to pregnant women and mothers of newborns, many of the same services the clinics in the Pregnancy Care Network are tasked to provide.

Each county’s Healthy Babies as well as their Healthy Start programs make their own goals, such as adopting a campaign to promote safe sleep behaviors or distributing education on breastfeeding. In each region, Florida’s Healthy Start and Healthy Babies programs must stretch their funding by forming partnerships to help pay for local initiatives.

While larger counties like Broward and Miami-Dade benefit, the financial structure disadvantages Florida’s rural areas with fewer private foundations and grant programs — but with a bigger need for resources and solutions.

Dawn Liberta says her nonprofit has to scrape for every dollar it gets. Liberta, executive director of Healthy Mothers Healthy Babies Coalition of Broward County, said her organization plays an important role in supplementing state efforts to reach high-risk pregnant women. Like other local Florida nonprofits, its efforts target underserved neighborhoods with programs that help with enrolling in Medicaid, locating a medical provider, improving nutrition, or providing emergency assistance for basic needs. It does not get funding in the state’s annual budget.

”We are funded by different foundations within the county,” Liberta said. “We have to fight for every penny.”

Where spending would deliver more benefit

Health experts and state officials agree there is no single solution to keeping more babies alive. But they all agree something needs to be done. Health advocates think state spending should be redirected to four key areas.

1. Insurance

Maternal and infant health experts point to the state’s health insurance system as detrimental to infant outcomes. Florida is one of 10 states that has opted out of Medicaid expansion to provide government health insurance coverage to low-income adults without dependents. As a result, Florida has a large number of mothers who lack access to affordable care and start their pregnancies with unmanaged chronic health conditions.

“We know that the health of babies is not just affected by the mom’s health during the pregnancy, but also before and in between pregnancies, so things like access to reliable and affordable healthcare matter, and a particular policy issue we hear a lot about is Medicaid expansion,” said Giridhar Mallya, senior policy officer at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

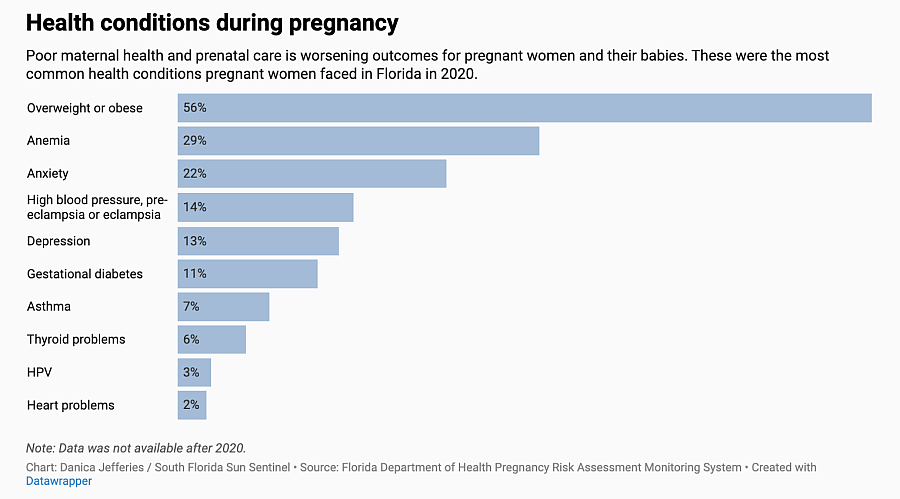

A woman’s chronic health conditions such as hypertension, anemia and diabetes can trigger pregnancy complications that lead to early births and deaths. Obesity has become an increasingly significant risk factor in Florida with rates at the time of pregnancy rising 35% in the last decade, and more in some of the state’s small rural counties, Department of Health records show.

Researchers think spending more on getting women insured, connected to primary care providers and educated on how to manage health conditions before becoming pregnant would pay off. “I think that would make a huge difference, a huge difference,” Dr. Shavonne Ramsey Coleman, South Florida medical director for Ob Hospitalist Group, which employs doctors to deliver babies as part of hospital staff.

Once pregnant, a Florida woman becomes eligible for Medicaid health coverage if she has been a US citizen for five years, and earns less than 196% of the federal poverty level, or about $26,500 a year as an individual. About 44% of births in Florida in 2022 were covered by Medicaid, according to the Florida Department of Health.

When women aren’t insured before pregnancy, the time-consuming process to get enrolled while pregnant often delays prenatal care. A 2023 study by Elevance Health, a large national insurer with plans in Florida, found that the emergency room often becomes an entry point for pregnant women to get enrolled in a Medicaid plan.

A growing number of women in the state are deep into their pregnancies when they finally are approved by Medicaid and see an obstetrician for the first time. From 2012 to 2022, the percentage of women in Florida getting first-trimester care declined from 80% to 76%.

Those women who successfully enroll say even with the coverage, it can be a battle to find a doctor who will accept the HMO insurance plan the system assigns them. If too much time passes, many obstetricians will deem an expecting mother to be high-risk and refuse to take her as a patient.

In Northwest Florida, a pregnant and frustrated Crystal Rosa tried to navigate the complicated Medicaid application process for six months. She went into early labor before she received approval. Without insurance, she never saw a doctor before the birth and emergency C-section.

“At first they told me they didn’t think she was going to make it,” Rosa said of her premature daughter. “I believe in God and miracles.”

Mother and infant are now covered under Medicaid. In 2023, a law in Florida extended the Medicaid postpartum coverage period from 60 days to 12 months, allowing Rosa to see a doctor for follow-up.

Rebekah Antoine, 33, of North Miami Beach gets her blood pressure checked during a prenatal visit in February at the Southern Birth Justice Network in Miami. Antoine, who was pregnant with her fourth child, has since given birth to a healthy baby boy.

(Carline Jean/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

2. Targeted spending on at-risk communities

Researchers now know that targeting spending to get more healthcare, health education and on-the-ground home visitors into high-risk neighborhoods with childbearing populations can result in better birth outcomes. Programs that educate mothers on safe sleep practices and the importance of early prenatal care can help curb infant deaths. Still, the infant mortality rates are worsening in some rural Florida counties, as is access to maternal health. Obstetricians are retiring or leaving the state, and labor and delivery wards are closing.

Dr. Marshara Fross, a University of South Florida perinatal and birth equity researcher, thinks Florida health officials should dig deeper into root causes of poor birth outcomes, uncover where and why infant death disparities exist within counties, and direct money where it would improve outcomes.

Palm Beach County, for example, has an infant mortality rate significantly lower than the state average. But in the far western part of the county, women in Belle Glade report a lack of maternal care providers and birthing hospitals.

“We’ve had a problem in Florida with using our data to drive our spending and our investments,” Fross said. “When we see problem areas, really targeting those areas would be ideal, but it seems like up until recently we spent a lot of time just highlighting the disparities instead of doing something about them.”

In a 2022 report, the March of Dimes found about 20% of Florida counties are maternity care deserts with no birthing hospitals or obstetric care providers. In those counties, pregnant women must travel up to an hour to reach the nearest birthing hospital. Most of the maternity care deserts are rural and located in the Panhandle, but some are in South-Central Florida, including Hardee, Glades and Hendry counties. And in 22% of Florida counties, women in underserved ZIP codes are highly vulnerable to complications due to a lack of nearby federally funded family planning clinics, the March of Dimes report shows.

As a result, women forego prenatal care. One in five mothers in Florida give birth without ever having received health care while pregnant, or only after seeing a provider close to delivery. Getting prenatal care that includes mental health care can be critical for managing chronic conditions and screening for smoking, substance abuse, depression, poor nutrition and other factors that could lead to low birthweight babies, infant deaths and preterm births.

“We need policymakers to look at these outcomes and say, ‘We need to do something for these women,’” said Carmen Giurgescu, professor and associate dean for research at the UCF College of Nursing. “The research is out there. The reports are out there. It’s not like the knowledge is not there. Now something needs to be done.”

Tamara Currin, director of state government affairs for the March of Dimes, said states that are directing funding toward examining ZIP code-level data are uncovering those less obvious barriers and remedying them. New Jersey, for example, has launched a statewide strategic plan after a year of looking into barriers and studying which communities most needed investment.

“There may be a place to go to receive those maternal health services, but there could be a barrier in terms of how you get there, or the amount of time it may take you to get there,” she said. “You even see some of the barriers in terms of depending on the type of employment you have. Are there extended hours at a clinic in your community where you can go after work hours to receive those services? Those are some of the unique initiatives that we see across the country that really get down to the core of what the need is for some families in these communities that we consider maternity care deserts.”

Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz gathered experts for a Black Maternal Health forum at the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Community Center in Hollywood on April 6 to help raise awareness to reduce maternal deaths among Black women, a group three times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related factor.

(Mike Stocker/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

Not every county has a private charity to come to the rescue. But in some counties where the need is great, private money is being successfully directed to women most at-risk.

In Broward County, Healthy Start took an in-depth look at ZIP codes with high rates of infant mortality. They discovered that while the county had numerous maternal care providers, two ZIP codes with a vulnerable population encompassing Oakland Park, Lauderhill and Sunrise had none. It took private funding to remedy the care gap.

Armed with the findings, the Health Foundation of South Florida has formed a collaboration with several local organizations and has stepped in with funding. Its initial $850,000 will be used to open a maternal care clinic in May for the underserved ZIP codes and staff it with obstetricians, doulas and midwives.The clinic in Broward County also will help with patients’ health-related social needs, such as stable housing, nutrition and transportation.

“We actually are in the process of approving a grant to provide transportation services to the clinic because sometimes that’s a barrier to prenatal care,” said Loreen Chant, president and CEO of the Health Foundation of South Florida. “Each community’s solution or effort is very specific to what’s driving the disparities in that community.”

Using another data set, her philanthropic foundation discovered another maternal care desert and formed a collaborative to fill a void in Monroe County.

“We know when there are maternity health deserts like the Florida Keys where there are only three OB-GYNs for 110 miles, we have pregnant women who don’t have access to prenatal care,” Chant said.

The foundation formed a maternal health collaborative once again, provided funding, and hired obstetrical staff. The collaboration now brings prenatal services via mobile units to existing clinics in the Keys not previously offering the care. As a result, since September 2023, 63 babies have been delivered with the help of the Florida Keys Health Collaborative, Chant says.

“We are seeing that our investments are paying off,” she said. “We have 15 organizations in our health collaboratives. We brought in an expert to provide technical assistance to them. We look at what’s happening in other communities and say, ‘Hey is this a model that we could try here in Florida?’”

She believes the state needs to bring community organizations, healthcare providers, philanthropies and government-funded programs together in neighborhoods where data shows infants are dying in greater numbers.

Chant says her foundation will track birth outcomes. “We will know what happened with those mothers in those communities that we’re serving and we’ll be able to compare … Did we actually reduce the disparities that we set out to reduce?“

In Duval County, Faye Johnson, executive director of the Northeast Florida Healthy Start Coalition, recognized the state funding her program received wasn’t enough to learn the root causes of infant deaths. She needed more data to understand why her region has averaged 100 infant deaths a year for the last five years.

March of Dimes highlighted Jacksonville in Duval County as one of the worst cities for infant deaths.

In 2018, Johnson secured private corporate donations and assembled a committee of health insurers, medical providers and community leaders who did a more in-depth review of infant death records, overall and by race. The review included interviews with every one of the mothers of the 147 babies that year who died before turning a year old.

They discovered key factors in those deaths were pre-pregnancy health of the mother, limited prenatal and postpartum care, lack of follow-up by mothers and medical providers, and “stressors” during pregnancy such as financial or domestic violence issues.

The results produced a list of recommendations that included a mobile pantry to distribute baby supplies to “resource-limited areas.” Then came the need for funding that concept. Johnson reached out to city officials. Now a nine-passenger van funded by the city of Jacksonville is equipped with diapers and wipes, formula, baby food, men’s and women’s toiletries, and pregnancy tests, many of the supplies donated by the Jacksonville Women Lawyers Association and Nemours Children’s Health.

“We have key stakeholders involved now,” Johnson said. “We have to get down to the local level and look at what more we can be doing.”

In a move to get more maternal health care into communities in need, Florida lawmakers allocated $4.8 million in 2022 for a pilot Telehealth Minority Maternity Care Program in Duval and Orange counties. Women who participate are screened and treated for pregnancy-related complications using remote patient-monitoring tools such as pregnancy blood pressure cuffs and glucose monitors.

“The patient can check her sugar at home, and that is immediately uploaded through the internet to a healthcare team so they can see real-time data,” Dr. Kenneth Scheppke, deputy secretary for health at the Florida Department of Health told Florida’s Senate Committee on Health Policy in November 2023. “Both pilot sites successfully identified chronic, underlying health conditions that put pregnant women at risk.”

In Duval County, 10 women were admitted to the hospital for preeclampsia (a complication of high blood pressure) detected through the program’s remote monitoring system, Scheppke said.

In 2023, Florida’s Department of Health expanded the pilot to 18 other counties. Florida health officials said in 2023 this program served over 3,700 women “with zero maternal or infant deaths among these clients.” In 2024, the state legislature expanded the telehealth program again, this time statewide with a $36 million budget.

“By implementing this program, the state anticipates a reduction in maternal and infant mortality while developing a framework to provide resources for overall improved health outcomes for moms and babies through the lifespan,” said Khoury at the Department of Health.

“I don’t think legislators are aggressive enough or give enough attention to Black maternal and infant health,” said state Sen. Rosalind Osgood, an outspoken advocate for Black maternal health who sits on the Florida Senate’s Health Policy Committee. “We cannot be OK with so many Black women and so many Black babies dying.”

(John McCall/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

3. Measuring results and taking action

What does Florida do with all the data it collects?

Not enough, health researchers say.

In 1992, Florida joined a national effort to review infant deaths in order to identify areas for improvement. The state allocated about $217,000 a year to its Fetal and Infant Mortality Review program administered through Healthy Start. However, less than half of the regions in the state had participated. The program has been underfunded, inconsistently utilized and has lacked a framework to turn findings into action. Local Healthy Start leaders have complained for more than five years that the budget wasn’t big enough to support comprehensive infant death reviews. The results of the review process were never compiled or shared on a state level, or tracked to ensure data evolved into action.

That may change.

A state mandate that went into effect as part of Florida’s 15-week abortion ban in 2022 now requires every region of the state to have a Fetal Infant Mortality Review Committee and the annual results, along with action steps, are reported to the governor. In 2023, more than 399 cases were reviewed, 20 community action groups were formed and action steps were proposed. A report with the results from the first year of implementation is due to the governor in October.

Florida’s hospitals collect data, too. The state spends money to help them.

Since 2010, the state has spent $2 million a year to participate in the Florida Perinatal Quality Collaborative, which encourages hospitals to collect information on the outcome of births, then use and share it to improve quality of care for new mothers and babies in the hospital and after discharge.

“It was 100% voluntary for the first 12 years that we functioned,” said Lori Reeves, executive director of the FPQC.

In 2021, only 76 of the state’s 106 hospitals with maternity units at the time participated.

Then, in 2022, a new state law mandated that every Florida birthing hospital with 100 deliveries a year participate in at least two of the Collaborative’s four quality initiatives. The requirement came with a $1.4 million funding increase for the Collaborative.

Reeves said all of the 104 maternity hospitals now open participate in at least two initiatives in 2024.

Dr. Todra Anderson-Rhodes is the first Black woman to be a chief medical officer in the Memorial Healthcare System and wants to see more physicians participate in quality initiatives and get a better understanding of where problems exist.

She participates in the Broward County committee that reviews all infant deaths each year and her health system’s task force to improve the quality of care. She wants to see more data brought to the attention of obstetric providers in a way they can relate to and act upon.

“We need to make the data come alive for practitioners,” she said. ”Some systems are doing it well and there are those who do it poorly. How can we hold accountable those doing it poorly? Who is going to the offices of practitioners caring for patients in ZIP codes that have the worst outcomes and ensuring an improvement in that care?”

Important questions need to be answered, she said.

“The amount of money Florida spends represents a big investment, but what’s the feedback loop, the return on investment, what have we learned and what are we doing about what we have learned?” she asked. “If you don’t ask and answer those questions, then we have wasted the money we are spending.”

4. Reforms in healthcare delivery and education

At health summits around the state, Black women and maternal care providers publicly are calling for reforms in Florida’s healthcare system, convinced some of the poor outcomes can be prevented. They want better-trained doctors, nurses and hospital staff who recognize the medical needs of women of color.

Ten years have passed, and Sandra Elidor, whose son was born at only 29 weeks, vividly remembers the emotionally charged environment of a Florida hospital’s neonatal intensive care unit.

“It’s that up and down. Will my child live? Will my child not live? Being at the NICU and praying for the other kids … I witnessed a mom who just left, probably still in the elevator, only to have a code blue for that baby.”

Elidor wants to prevent more parents from going through the trauma she says resulted from her younger days when doctors misdiagnosed her endometriosis. Her son is now 10. Still, she wants to see changes in Florida’s healthcare system to combat inequalities in care.

Frustrated Florida women like Elidor are calling for state policies that address biased care practices, reduce unnecessary cesarean sections, and offer incentives for more Black medical students to become birthing professionals.

Sandra Elidor’s son was born at only 29 weeks, and 10 years later, she still vividly remembers the emotionally charged environment of a Florida hospital’s neonatal intensive care unit. “It’s that up and down. Will my child live? Will my child not live? Being at the NICU and praying for the other kids … I witnessed a mom who just left, probably still in the elevator, only to have a code blue for that baby.” She attended the Black Maternal Health forum in Hollywood.

(Mike Stocker/South Florida Sun Sentinel)

Dr. Stevenson Chery, medical director at BCOM Health, a government-funded health clinic in West Park in Broward County, said Florida lawmakers’ recent push to remove Diversity Equity and Inclusion requirements at higher education institutions has a chilling effect.

“That impacts what we are trying to do,” he said “Patients cannot access physicians who look like them within the system.”

Black women are more likely to experience life-threatening conditions during pregnancy like preeclampsia, postpartum hemorrhage and blood clots, as well as increased chances of preterm birth. But not all doctors recognize the signs or teach their patients to recognize them.

Dr. Coleman, an obstetrician, sees that firsthand when mothers arrive at the South Florida hospitals where she works.

“A lot of the providers are not doing the best job,” she said. “You know, we have to listen to our patients. We have to give them the appropriate care. We have to give them the time they need to express themselves.”

Coleman believes the state needs to provide incentives to hospitals to bring OB-GYNs on staff and include doulas and midwives in their obstetric teams.

“It really should be the standard of care,” she said. “Having 24/7 in-house access to OB-GYNs for emergencies should be the standard of care.”

In the last two years, as state lawmakers passed laws to restrict abortion, they also have approved some new initiatives and funding that may improve maternal and infant health.

During the 2022 legislative session, lawmakers amended Florida statutes to expand services provided by Healthy Start to include father engagement activities and allocated $4.4 million in state funds.

The biggest impact may come from Florida’s newly approved Live Healthy legislation.

Championed by Senate President Kathleen Passidomo, the bill includes three initiatives aimed at expanding access to infant and maternal health:

- Higher Medicaid reimbursement for hospital labor and delivery services, which could prevent more of these hospital units from closing.

- A new “advanced birth center” designation for 24/7 free-standing centers, which will be allowed to perform planned low-risk C-sections.

- A change in regulations to make it easier for independent nurse midwives to practice in the state. Black women who previously had bad birth experiences are using midwives more often for their care and delivery, according to Urban Institute, a Washington, D.C.–based think tank that conducts economic and social policy research.

Wikinson, the Indiana professor, said Florida needed to make these investments and should consider more. ”I hope state leaders are saying we have to do something different if this is our plateau.”

With abortion restrictions going into effect, she expects to see national infant mortality rates rise, and Florida to be a contributor. “The statistics are going to be way worse. We’re just at the beginning of the tsunami. We just got the warning shot,” she said. “The wave hasn’t even come yet.”