‘Backpacks full of boulders’: How one district is addressing the trauma undocumented children bring to school

This story is part of a larger project by Kavitha Cardoza, a participant in the 2019 National Fellowship, who is exploring the unprecedented challenges education professionals must address when they attempt to create and manage programs and services to support undocumented children who are navigating life in a foreign country.

Other stories in this series include:

How Prince George’s County Is Adapting To A Growing Number of Unaccompanied Children

Listen To Part 4: Prince George’s Schools Welcome Undocumented Students By Respecting Their Past

Pat Chiancone is in charge of international student enrollment in Prince Georges County schools. She says there has been a “staggering” increase over the past several years of undocumented students enrolling there. While the trend slowed this year, she says, “I absolutely think that the numbers will go right back up when the pandemic passes. No doubt.”

Credit: Tyrone Turner for WAMU

ADELPHI, Md. — When Nando was in the fourth grade, his older brother was killed by gangs in El Salvador. His mother was terrified for his safety, so Nando stopped going to school. For years, he stayed indoors.

“It felt like prison,” he said.

Nando’s family struggled to put food on the table. They grew increasingly desperate. So, at 16, he decided to make the treacherous journey to the U.S., leaving behind his parents and younger brother.

“I had a coyote who was helping me, but halfway through, he took my money and left,” said Nando. He worked on a farm in Mexico for two months to make enough money to continue the journey. “I was sad, I was tired, I felt desperate.”

He applied for political asylum, and after six months in two detention centers, his aunt in Maryland sponsored him. Nando is his middle name; to protect his privacy and safety, he asked that his full name not be used. He was just settling into a routine at school when he learned gangs had murdered his other brother.

“We were three. Now it’s only me,” he said.

Since 2013, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of children like Nando fleeing poverty and violence in Central America. The Trump administration expanded detentions, increased family separations, narrowed asylum criteria and canceled funding for the legal representation of undocumented children. Still, between October 2018 and September 2019 more than 75,000 unaccompanied minors — children who arrived in the U.S. without a parent or guardian — and almost 475,000 family members, including children, were apprehended crossing the southern border.

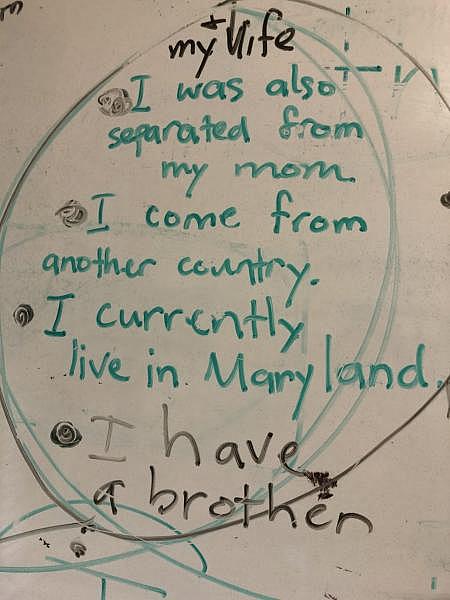

A whiteboard in a classroom. Educators encourage students to share their personal stories as a way to feel proud of their heritage, recognize how strong they are and process trauma. Credit: Kavitha Cardoza for The Hechinger Report

Most of the attention has focused on the poor conditions and children’s traumatic experiences in detention centers. But if they ask for asylum and are released to family members or sponsors in the U.S., it can take as long as five years for their cases to wind through the backlogged legal system. During that time, like other immigrants in the U.S. without official sanction, they are considered “undocumented.” Meantime, most of the children enroll in U.S. public schools, which are often the first places that they encounter Americans who are not law enforcement. And while not every one is welcoming, school is often the first place the kids say they are treated with kindness.

But in some school districts, before the pandemic hit, educators had begun going further, intentionally overhauling their classes and moving around resources to help these children succeed.

In Prince George’s County, Maryland, just outside Washington, D.C., where Nando enrolled, school leaders recognize that their district’s future depends on undocumented students doing well. In 2019, it ranked fourth of all counties in the U.S. in the number of incoming unaccompanied children released to sponsors, behind only Harris County, Texas, Los Angeles and Miami-Dade. Pat Chiancone is in charge of international students in Prince George’s County Public Schools and says that 10 years ago they enrolled fewer than 4,000 international students in the district. Even with coronavirus-related travel restrictions, this year the district enrolled more than twice that number, Chiancone said.

Having so many children arrive through the year who are encountering a new language, new culture and new family life can be a tremendous strain. Many undocumented students struggle with basic needs like food, housing and health insurance. Chiancone says many also have large gaps in their schooling, so they are academically behind, even in their home language. But what might be perhaps the single most defining characteristic of this population is the considerable trauma they’ve experienced — in their home countries, during their journeys here and after they’ve reached the U.S.

Cooper Lane Elementary School in Maryland’s Prince George’s County school district had almost 550 children, 60 percent of whom are Hispanic. Credit: Tyrone Turner for WAMU

Alvin Thornton, the long-time chairman of the Board of Education of Prince George’s County, lists several reasons why it’s important to do whatever it takes to support these children, not least because it’s federal law. “But for me, the most important reason is it is morally, really spiritually, inappropriate to mistreat the children who come from these families and not give them equal opportunity,” he said.

“For me, the most important reason is it is morally, really spiritually, inappropriate to mistreat the children who come from these families.” - Alvin Thornton, chairman of the Board of Education of Prince George’s County

Nando’s mother texts him to make sure he’s still alive. He lives alone in a rented room and has a part-time job after school where he works from 4 p.m. to 1 a.m. “I need money for rent, food and clothes. I send $300 to my mother every month. I have to pay my lawyer $6,000 for my case.” He laughs wryly. “Yes, I’m very tired.”

He’s thought about dropping out of school several times but each time he’s returned.

In October, 2019, Prince George’s educators voluntarily crowded into a community center for a five-hour seminar, on “trauma informed care” for immigrant populations, with an expert from Harvard University. Dr. Margarita Alegria is chief of the Disparities Research Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital and a professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. The district flew her in with the help of two nonprofits, Catholic Charities and the Interfaith Coalition for Educational Equity, to help its educators understand how to support the large waves of students crossing the border and enrolling in the school district. The teachers were hungry for information; 150 had given up a sunny Saturday to join the session.

Kevin O’Donnell, a school psychologist, wanted practical suggestions. “A lot of my students have experienced trauma, and they struggle. I wanted to learn about more supports that work,” he said. Andrea Stutzman is a teacher who wanted to learn to better connect culturally with parents: “I think it would help me understand my students’ experiences more.” And Jeffrey Ramirez, a security guard, was looking to learn more about what his students have experienced, so he could reassure them that he won’t hurt them. “I say, ‘I don’t know what you went through in your country, but this is different.’ If they fled because of violence, they can feel safe here, and they can feel safe with me,” he said.

The atrium at Mary Harris Mother Jones Elementary school in Prince George’s County, Maryland, is lined with flags from different countries, including those in Central America. The recently retired principal Dr. Karen Woodson hopes that when children recognize their flag, they know they are welcome. Credit: Kavitha Cardoza for The Hechinger Report

It’s not uncommon for children to talk about seeing women raped or people left behind when they couldn’t keep up on the journey to the U.S. Berta Romero is a counselor for English learners in Mary Harris Mother Jones Elementary school in Adelphi. The stories she hears are awful. One second grader said her mother had to cover her eyes because people were drowning in a river they were crossing. Another child talked about the journey to the U.S. in a crowded truck and his father having to push him above everyone else just so he could breathe. A mother tearfully recounted to Romero how MS-13 gang members were molesting her daughter on her way to school. Romero says the weight of these experiences is like children “carrying a big backpack with boulders in it.”

When the children reached the U.S., the trauma for many continued, as the Trump administration separated families in detention centers where cells were sometimes kept frigid, food was inadequate and kids were not given access to basic hygiene. Several children said the adults there threatened them when they broke one of the many rules — no talking, no making friends, no playing

Kerri Bogart is a kindergarten teacher and has worked with a lot of these children. She says some are “silent criers” — they just sit with tears streaming down their cheeks because they miss their families back home. Sometimes it’s random outbursts of anger or tears: “Is mommy going to be at the bus stop? I’m worried that she’s not going to be there.” One of her kindergartners would get upset and crawl under the table, and she would have to stop the lesson to coax him out. “When that’s happening three, four or five times a day and you’re missing out on that instruction, that can be very harmful,” she said.

Berta Romero is a counselor for English learners at Mary Harris Mother Jones Elementary school in Prince George’s County, Maryland. It’s a new position that was created before the pandemic, to help undocumented children. She says many have been through very traumatic situations. “Having those flashbacks all the time and living with that is not easy. It’s not easy.” Credit: Tyrone Turner for WAMU

Teachers have to understand the root of these behaviors, and how to handle them, before any learning can take place. At the seminar, Alegria explained the “compounded loss” children experienced when they fled their homes. “They lost their familiar language, their customs, their habits, they lost their social networks. And many of them have lost their social status,” she said. Alegria told the teachers they have a critical role to play. “Schools are where kids spend most of their time. It’s really the system of care where we can make the biggest gains,” she said.

Alegria warned the educators that trauma can manifest as physical problems — headaches, stomachaches, insomnia — in addition to learning problems. She says teachers shouldn’t assume a lack of concentration is attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; it could be that the students are trying hard to deal with their trauma. For older youth, Alegria says, social status is very important. She told educators that helping these children make friends has a “super powerful effect.”

Beth Hood, a social worker at High Point High School in Prince George’s County, says sometimes a child can seem OK but then something will trigger a flashback. One student had a panic attack after seeing a small fight break out in the cafeteria. “After that event, she completely just spiraled downward, couldn’t focus, and in class was often tearful.” Hood said that after talking to the student about what caused the panic attack, the girl opened up.

“She talked about having witnessed her best friend being killed in her home county,” she said. “Our students are not students that you can expect to just go into the classroom and learn English and be fine.”

Undocumented students enter public schools with lots of challenges to overcome, but also lots of strengths. Teachers say they are very hard-working, resilient, look out for each other and are eager to learn. Prince George’s schools have focused on three areas to support these children — improving their language skills, being inclusive and building resilience.

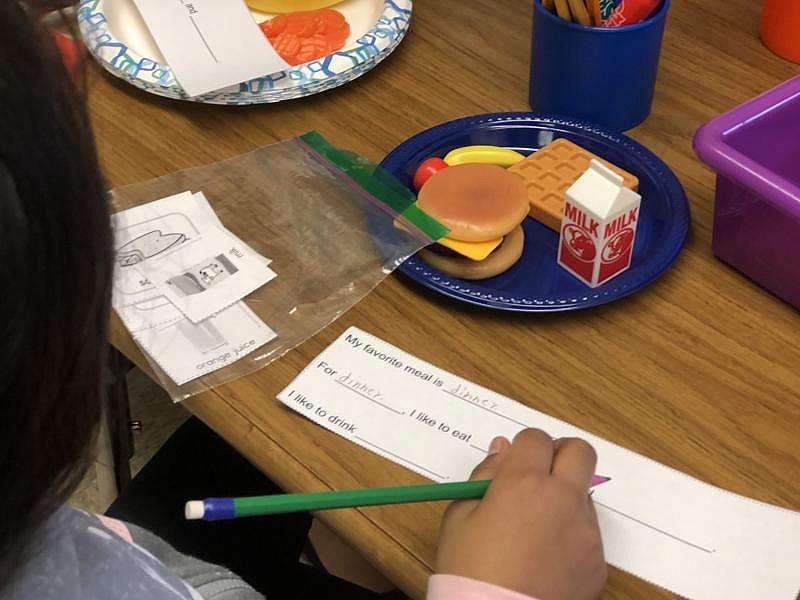

A 6-year-old English learner picks out plastic toys representing his favorite foods. He is getting ready to write a sentence about the foods, which he will read out loud. Credit: Kavitha Cardoza for The Hechinger Report

Learning English is an obvious but critical step. Apart from helping the students succeed academically, it’s a way to make friends, translate for their parents and navigate their new culture. It’s also a way to share their stories and feel like they belong.

There are over 27,000 English learners in this school system, so the district has also made a big push to support regular classroom teachers. They’re taught strategies like using visual aids and hands-on learning.

Christian Rhodes is the chief of staff to the Prince George’s County Public Schools superintendent. He said that prioritizing initiatives for these children is about equity because “for many, the schoolhouse is a refuge.” But Rhodes also says it’s about demographics. Children considered “subgroups” in many suburban districts, such as English learners and children in poverty, collectively make up the majority of the county’s students. “That is our core base,” he said. “And we make decisions as a school system based off of the population of students we have.”

Rhodes said it’s “wrong” to believe they have a host of additional resources to help educate these children. Rather, “budget is a function of priority.” The district has also allowed principals a level of fiscal autonomy so they can fund priorities based on their school’s needs. In addition, he says the district partners extensively with county agencies and area nonprofits. And while districts in Maryland did receive additional money for vulnerable students as a “down payment” after the state passed the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future Act, Rhodes says that funding will expire in June 2021 if lawmakers don’t act. He says legislators must act now because given trends in immigration and the added challenges because of the coronavirus, “I think every district in the country is going to see a surge next year when it comes to need.” Those funds are sorely needed because Prince George’s County, like school districts across the country, is anticipating “funding shortfalls” and a “significant deficit” for the next academic year.

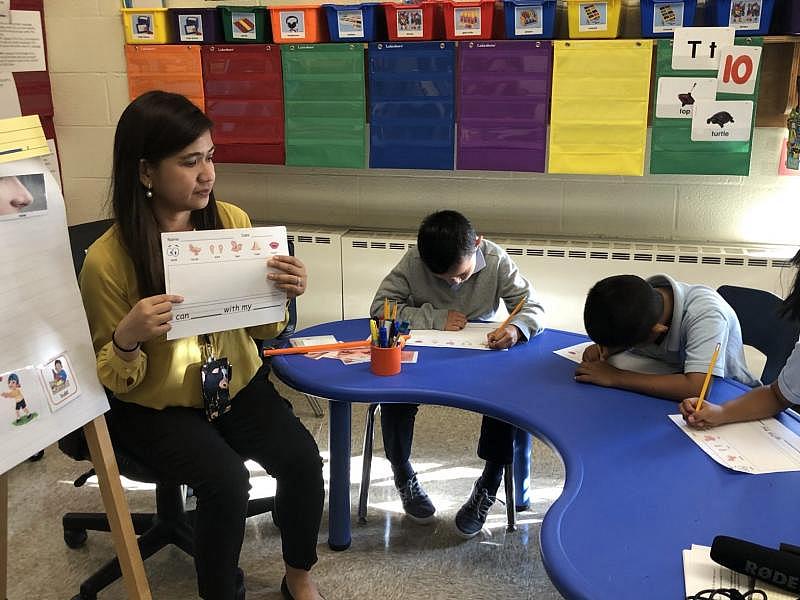

Last year, Prince George’s County schools created a “newcomer curriculum,” a 12-week course that every student who didn’t speak English and was new to the country would take to quickly build English vocabulary.

Tanya Gan Lim teaches a “newcomer class,” which Maryland’s Prince George’s County school district created for children who have been in the U.S. for less than a year and are learning English. They focus on themes the children use in everyday life, such as the weather, body parts and transportation, to help them build vocabulary. Credit: Kavitha Cardoza for The Hechinger Report

Tanya Gan Lim teaches this class to kindergartners. They focus on practical themes, like transportation, the weather, food. But she’s also focused on building confidence. Lim encourages her students to speak. “When they’re in the mainstream classrooms, they feel shy, they don’t want to talk because they don’t want to make mistakes,” said Lim.

Ana, a kindergartner, is more confident after just two months in the newcomer course, though she still needs practice sounding out certain syllables. She wants to learn English to “be smart” and uses Google translate to look up words she doesn’t understand. There’s also a more practical reason: At age 7, she needs to translate for her mother in the grocery store. “If we go to somewhere and my mom says ‘How much?’ and I say is three dollar or four dollar. And she is happy. She say, ‘I love you.’ ”

Celebrating the strengths these children come with is another way to build their confidence in school. At Mary Harris Mother Jones Elementary, Principal Karen Woodson was a master at making everyone feel welcome, documented or not. The school has seen dramatic increases in the number of newcomers, who now make up 16 percent of the student body, she said.

Woodson recently retired, but many of her policies continue. While she was still principal last winter, she walked through the building, pointing to the large flags hanging in the atrium, the first things children see as they enter the school. “They’re going to recognize El Salvador right away. Every country in Central and South America is represented here,” she said. She hopes when children recognize their flag, they know they are welcome. There are also signs posted all over school that say “Being Bilingual is my Superpower.”

Woodson is African American and switches effortlessly between English and Spanish. She says parents and children are astonished when they first hear her. “First I get, ‘Wait, why are you speaking in Spanish?’ And then the next question I get is, ‘Well, where are you from?’ And I go ‘from New York,’ and they go, ‘What?!’ ” She uses that opportunity to explain that she didn’t grow up speaking Spanish, she studied it, just like they are studying English. “I did the same thing and I took the time. And you can be fluent, too.”

Prince George’s County Public Schools has resources in both English and Spanish for English learners and their families. There are more than 27,000 English learners in the district. Credit: Tyrone Turner for WAMU

Front office staff in the school are bilingual and any sign in English is also posted in Spanish — from the school entrance to the trash cans. The school stocks several Spanish titles in the library, and Woodson encouraged the children to keep up their Spanish. Woodson says these small efforts help all students see there’s no language hierarchy.

Alegria said that respecting a child’s family culture isn’t just to be “nice,” it’s actually better for children’s development. She says children can end up learning to navigate both cultures very well. But in the beginning, they have to feel “anchored” in their own culture.

Principal Woodson also beefed up support staff. With the flexibility she had in her budget, last year, she hired three additional bilingual teacher aides. The school also hired a bilingual counselor, who can support teachers, do home visits and meet individually with children who are struggling, and a bilingual community liaison who can connect newcomer families to outside services.

“I finish school at 2:30 and then work from 3:30 to 11. Even one dollar here is a lot of money in Guatemala.” - Undocumented student Luis, who works in a grocery store

But Woodson, who is now a consultant supporting leaders in schools with high numbers of English learners, warned that even with these supports, none of this is easy on educators. “With the influx, I have to be very honest. Teachers are tired. It’s a lot.” She said she encourages teachers to talk about how they feel and support each other. “But guess what? We’re tired but committed. We will rest but there’s no quitting.”

Being able to build relationships and have a voice is a critical way for undocumented students to integrate and counteract some of the trauma they’ve faced. So Prince George’s County is intentionally focusing on mental health.

Social worker Beth Hood says that there are about 300 newcomers at the high school. She organizes “circles” to support them. Their English is very limited, so she speaks in Spanish and starts with very basic aspects of U.S. education, from the layout of the building to the role of school nurses to the expectation that students come to class every day. But she also encourages them to share their stories about where they came from and what their lives were like before.

Social worker Beth Hood says that there are about 300 newcomers at the high school. She organizes “circles” to support them. Their English is very limited, so she speaks in Spanish and starts with very basic aspects of U.S. education, from the layout of the building to the role of school nurses to the expectation that students come to class every day. But she also encourages them to share their stories about where they came from and what their lives were like before.

“It’s important for them to talk about how they used to tend to cows or how they used to make tortillas or how they used to help their grandmother go to the market,” she said. “These are real life day-to-day strengths and experiences that they bring.”

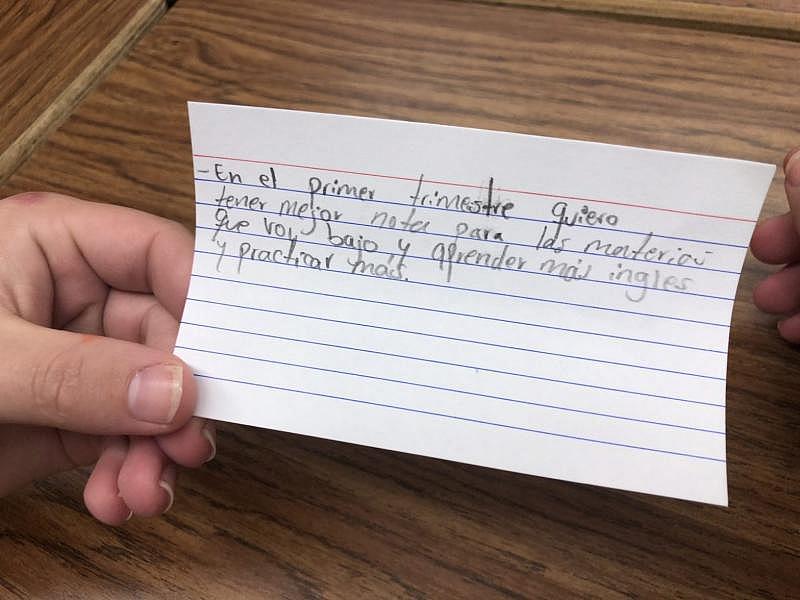

Many of these students came as unaccompanied minors and often don’t trust adults. So Hood says that the circles are a way for the teens to make friends with others like them, so they don’t feel alone. Coping skills promote healing. Hood teaches the students breathing exercises, and they discuss how to solve conflicts. On a cold winter morning, they worked in groups, listing factors that help them do well.

One student reads her list. “Confidence, family love, patience, advice from parents and learning English.”

Another student shares what motivates her to do well. “Going out with new friends, supporting each other, continue to push forward every day, learning new things every day, new opportunities, new places.”

At every opportunity, Hood praises them for sharing and encourages them to be optimistic. It’s a way to build their resilience, reminding them how far they’ve come. Sometimes she brings in former students who are also undocumented or who also came as unaccompanied minors and who stayed in school and graduated.

“We’re tired but committed. We will rest but there’s no quitting.” - Former principal Karen Woodson, whose school had a surge of undocumented students

In 2014, when there was a big wave of unaccompanied minors in Prince George’s County, teachers here asked the principal to create a social worker position, instead of hiring another teacher. The principal agreed, and last year the school added another.

Hood says focusing on supporting kids’ mental health is key to getting them to succeed academically. That’s because it’s a constant struggle for many newcomer teens to stay in school. They feel an immense sense of responsibility to their families back home. So they take jobs working in factories, restaurants, cleaning. “It’s the most arduous, crappy jobs that are available,” said Hood. “That’s where the temptation hits, is that they’re able to make money that they’ve never made in their lives, and they’re able to support their families back home somewhat.”

One of Hood’s students, Luis, was 16 when he fled violence in Guatemala almost two years ago and arrived in the U.S. His first language is Mam, an indigenous language. He spoke little Spanish and no English. Luis now works in a grocery store. “I finish school at 2:30 and then work from 3:30 to 11,” he said. He needs every dollar to repay his coyote who smuggled him into the country, to pay his lawyer, to pay rent. And he sends money home. “Even one dollar here is a lot of money in Guatemala.”

At first when customers asked Luis something, he wasn’t able to reply. “Then I practice more, practice more, practice more. Now I help them with everything, no problem!” he said. Luis squeezes in homework after work. But, he admits, sometimes it’s hard to wake up.

As part of a class exercise, Beth Hood, a social worker in Prince George’s County, Maryland, asks students to write out what their hopes are for the next semester. Several students say they want to improve their grades and learn more English. Credit: Kavitha Cardoza for The Hechinger Report

Hood says most of her newcomer students start off very motivated to do well in school, “but when it comes down to it, their physical body can only sustain that amount of work and studying.”

“With the unaccompanied minor students,” she adds, “we see them leaving school at a much, much higher rate.”

At the end of the class, students begin joking around while working on the assignment. Hood is visibly delighted. It’s a completely different vibe from the start of the school year, when they barely spoke to each other and everyone looked terrified. She says her school intentionally creates opportunities for newcomer students to have fun. Last year, the principal organized a holiday lunch just for them, complete with a D.J., because the holidays — and memories of years past with their families — are so hard.

“They all danced, and the kids danced with the staff. And it was just pure joy,” Hood said. “It brings that sense of compassion and love and joy into the school building. And we know that every positive experience that immigrant youth have builds resilience and trust.”

Prince George’s County has shown a real commitment to educating these undocumented students, but everything is much harder to do now that the district has moved to remote learning because of the pandemic. Teachers talk about how difficult it is to develop relationships online. Some of the districtwide language initiatives, such as using visual aids and hands-on learning, are almost impossible for students with poor internet connections, without basic supplies like paper or pencils or with a baby crying in the background.

Tanya Gan Lim a teacher at Cooper Lane Elementary School in Prince George’s County, Maryland, is a former English learner herself, so she understands how challenging it is for her students. “When they’re in the mainstream classrooms, they feel shy, they don’t want to talk because they don’t want to make mistakes,” says Lim. Credit: Tyrone Turner for WAMU

Teacher Tanya Gan Lim says she worries that her students aren’t hearing English in the hallways or on the playground now that they aren’t in school. Prince George’s County distributed free Chromebooks and mobile Wi-Fi units but often these kids and their relatives don’t know how to log on or how to troubleshoot. Social workers say their days are spent doing tech support or trying to locate kids who aren’t attending classes during the pandemic. Many parents or guardians have been laid off or have seen their hours cut, so these undocumented students feel an increasing pressure to get jobs that can help pay the bills.

The number of people crossing the border is now increasing. Apprehension numbers, often used as a proxy for whether undocumented immigration is increasing or not, plummeted earlier this year in part because of the Trump administration’s emergency health restrictions to expel everyone at the border, including children, to prevent the spread of coronavirus. A judge recently restricted that order.

The Biden administration has indicated they’ll push for several immigration changes, including a “pathway to citizenship” for the millions of undocumented immigrants in the country. Pat Chiancone, who runs the international student office, says she expects the numbers of children crossing the border and enrolling in area schools to climb. “I absolutely think that the numbers will go right back up when the pandemic passes. No doubt,” she said.

But it’s clear that undocumented students want to learn and can be successful. After years of struggle, Nando graduated high school this year. He wanted to show his mother he could achieve something. “I wanted to do this for her. We miss each other so much.”

He had dreams of becoming a doctor, but for now he’s working as a painter. He’s grateful to his teachers who supported him and wishes everyone would see him the way they did. “We are here because we want to improve our lives. To have a better life.”

This story about undocumented students was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

[This story was originally published by The Hechinger Report].