Butte County Mental Health Diversion court brightens futures; challenges remain

The story was originally published in the ChicoSol News with support from our 2025 National Fellowship.

Mental Health Diversion court takes place at Butte County Superior Court monthly.

(ChicoSol was unable to get permission to take photos of the proceedings.) Image by AI.

Michael, then a defendant in a Butte County Superior Court vandalism case, was standing at what a judge called the “finish line.”

“My life’s changed in three years,” Michael said, adding that he has learned more about trauma, self-reflection, psychology and empathy.

“Your case has been dismissed. Congratulations,” the judge said, as applause filled the courtroom on a morning in early August.

Butte County’s Mental Health Diversion program offers defendants a second chance at a future free from convictions or criminal records by focusing not just on punishment, but also on getting those in trouble the help they need.

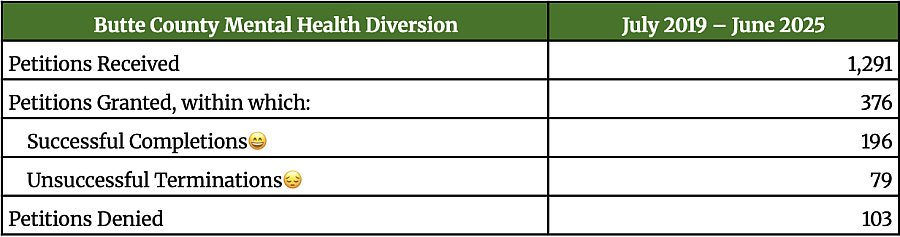

Some attorneys, however, say the program is underused — just under 200 people had successfully completed the 6-year-old Mental Health Diversion program in Butte County by the end of June 2025. The challenges to a successful completion are considerable.

The program, authorized under a California state law, allows eligible defendants charged with certain crimes to postpone prosecution and receive court-ordered mental health treatment instead of jail time.

Successful completion results in dismissal of charges, as it did for Michael and about five other people who graduated that day.

The idea is not just to change outcomes for individuals, but to ease pressure on overcrowded jails by diverting people with treatable mental health conditions, reduce recidivism by addressing the root causes of crime, and balance public safety with defendants’ needs.

According to the Vera Institute, an organization working for criminal justice reform, 57% of individuals held in Butte County Jail in 2022 were identified as having mental health needs.

But not just anyone can successfully graduate from the Mental Health Diversion program. Getting admitted is the first challenge, and to qualify, defendants must be diagnosed with a recognized mental health condition such as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, PTSD, or certain substance use disorders. (Charges involving alleged murder, voluntary manslaughter, rape, or a sex offense may automatically exclude a defendant.)

Once admitted, the program can be more challenging for low-income defendants in a rural or semi-rural area like Butte County.

Defendants on Mental Health Diversion attend monthly court reviews, allowing the judge and district attorney’s office to monitor treatment progress for one year in the case of misdemeanors, and two years in the case of felony charges.

“It is a really long time to keep coming back to court and showing that you’re in compliance with your treatment,” said Andrea Crider, a former public defender who has researched the program in California and now teaches at UC Berkeley law school.

Andrea Crider

Getting admitted, reaching completion

Since Butte County launched its program in 2019, until June 2025, only about 29 percent of the petitions from defendants seeking entry were granted, according to data ChicoSol obtained from the California Judicial Council.

And of those who were admitted, only about half completed the program successfully. Among the cases still in the diversion process, the risk of termination is also not uncommon, based on this reporter’s courtroom observations.

Data source: the California Judicial Council.

Table made by Yucheng Tang.

Applicants may face objections from the District Attorney’s office or Behavioral Health, and then ultimately be denied entry. Even after being admitted to the program, diversion can be terminated because of poor attendance and compliance or lack of a progress report.

At diversion court, held the first Tuesday of every month, the judge, the DA, Butte County Behavioral Health, defense attorneys and the defendants themselves all play a role.

Facing objections: Sometimes it’s the prosecutor, sometimes another party

Shortly after Michael’s graduation, a defendant came out from behind the courtroom wearing an orange jail uniform. He was appearing for what’s called “suitability” determination –the last step before the court approves the petition and admits the defendant to Mental Health Diversion.

Elizabeth Latimer, a Chico attorney, explained that diversion cases must first pass an eligibility determination in criminal court and then proceed to Mental Health Diversion court for a suitability hearing.

“That’s where the battle is,” she said. “Eligibility is usually pretty clear. But suitability determination is where the grey area is and where people can fall through the cracks if no one fights hard for them.”

In this case, the man faced multiple charges that included burglary, vehicle theft and use of tear gas. His petition to participate in diversion said he had been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, amphetamine use disorder and opioid use disorder. He had been a victim of childhood abuse.

A clinician at Behavioral Health suggested the defendant would respond to treatment, according to the court filing, but Chief Deputy District Attorney Mark Murphy opposed the petition.

Murphy said there was no analysis or evaluation about whether the defendant has anti-social personality — a diagnosis that would automatically exclude him — and he had no confidence the man would meet court requirements based on his history.

The case was moved to an October hearing to further determine suitability.

Murphy objected to a couple of other petitions explicitly on Aug. 5, and supported other petitions with extra requirements, such as adding a 52-week batterers’ intervention program to the treatment plan.

At the Sept. 2 hearing, a case involving a love triangle drew a strong objection from Murphy. He argued that the attack on the victims was driven by jealousy rather than a mental health disorder, and that the evidence showed her offense was not an impulsive act but a premeditated one.

Murphy tried to show that the mental illness of the defendant, a young woman with a ponytail and black-rimmed glasses, was not directly related to her criminal behavior.

Leah Sears, the court commissioner that day, nevertheless approved the petition. Sears pointed to the legal standard: If a defendant has been diagnosed with a mental disorder, the court must presume it played a significant role in the offense—unless there is clear and convincing evidence showing otherwise.

After stepping down from the defendant’s bench, the girl trembled and sobbed quietly while looking over the documents in her hands.

Behavioral Health, sometimes, may choose not to recommend a defendant for diversion.

On Sept. 2, a petition was denied due to the lack of a treatment plan. A Behavioral Health representative explained that a particular defendant lacked a sufficient support network. In Mental Health Diversion, participants are expected to have a support network comprised family members and friends who can help them walk the journey.

Commissioner Sears denied the petition and asked the defendant’s lawyer to work with Behavioral Health on a potential treatment plan if there is a re-application.

Terminated without success

For those who are already in the program, there is no guarantee of successful graduation.

According to the California Judicial Council, 376 petitions were granted in Butte County through June 2025. About 21 percent were terminated unsuccessfully.

Overworked public defenders, stringent eligibility criteria, and a lack of resources in rural areas have created a system where access is often determined by geography and luck rather than need”

Andrea Crider

Murphy’s motions to terminate diversion were often made in response to a lack of progress reports or absence of treatment. In cases with good reports, Murphy congratulated the defendants.

Christina, a woman who was admitted to Mental Health Diversion, addressed the judge over Zoom. She moved to Santa Cruz earlier this year, and was having difficulty finding a Medi-Cal-covered therapist.

“I lost my therapist,” Christina said, her voice tinged with desperation. “I contacted every single provider in the county. That’s a nightmare for me. I hope the court can understand that all those missing reports happened after I moved to Santa Cruz to take care of my family.”

Murphy responded, calling out every month that missed a progress report. “I understand what you are saying, but the pattern we see here is serious — no report,” Murphy said.

Murphy warned that if there is no treatment record the next month, he will move to terminate her program. The judge scheduled a review hearing and asked her to keep in touch with the public defender, who might be able to help her locate service providers.

“A regular check-in with a kind judge is a crucial piece for people navigating the criminal justice system” — Elizabeth Latimer

Crider noted that the Medi-Cal is typically connected to the county where people reside, so sometimes a move to another town can pause their treatment and get them into trouble.

A young man who appeared in court wearing a dress shirt had missed a treatment appointment in July because of transportation obstacles. That appeared to be a common problem among Butte County defendants.

Although his case wasn’t terminated — he was only warned — another ongoing diversion case was terminated at the prosecutor’s request. Murphy said the in-custody defendant, Lukas, was unable to remain sober and required more assistance than the program could provide.

James Petelin, Lukas’s public defender, said his client was struggling with a mental health disorder and addiction, but was working through it.

Commissioner Sears nevertheless terminated diversion and Lukas now faces prosecution.

Harder for the indigent

Attorneys told ChicoSol there is often a huge disparity between poor and wealthy defendants in their ability to access and succeed in Mental Health Diversion.

Elizabeth Latimer

Chico attorney Latimer co-founded Butte Defense Equity Project in 2020, a nonprofit indigent defense organization that provides legal help and resources for under-resourced individuals who become involved in the criminal justice system. She has fought to get some clients into a program that she believes is a pathway to improved public safety and rehabilitation.

“If you are poor and cannot afford a [private] attorney, you will likely be treated by Behavioral Health, whereas people who can afford an attorney often have a private practitioner,” Latimer said. “This can be an important point of divergence in terms of resources directed towards someone’s mental health improvement.”

Latimer also mentioned that the mental health care operations and services in Butte County are few, and Behavioral Health can be overloaded.

Ashley Starr, a Behavioral Health clinician who acts as liaison between that county agency and the court, attends the hearings. When this reporter attended hearings, the judge sometimes referred a defendant to Starr and asked her to make an assessment and work out a possible treatment plan.

“Sorry, I just gave you more work to do,” Rodriguez said at one point, suggesting he is familiar with the agency’s limitations. “I hope it will not burden you too much.”

Public defenders are sometimes stretched thin by the requirements of Mental Health Diversion court. James Petelin is the primary public defender in Butte County Mental Health Diversion court.

Image by AI.

The public defenders can also be overburdened. At Mental Health Diversion court in Butte County, Petelin is the primary public defender assigned to indigent defendants. There were 66 defendants at the Aug. 5 hearings, and Petelin represented 71 percent of them. He even momentarily mistook this reporter for one of his clients.

At the September hearing, a homeless elderly woman, represented by Petelin, said she had struggled to attend online monthly reviews. It was challenging for her to find a place with Wi-Fi at a specific time with an already-charged phone, she said.

A 23-year-old mother, who started the diversion program in December, got her “worst” progress report in August. She explained to the judge that she has ill children and her 15-month-old daughter had been in and out of the hospital. Rodriguez said he would give her another chance to show compliance.

Poverty isn’t just about lacking money, but also about being time-poor, said Crider, who worked as a public defender in Contra Costa and Solano counties.

“Going to doctor appointments, like doing all these things, is really difficult when you’re still very much in survival mode on how to pay rent and feed your children and deal with your citizenship,” Crider added.

In an article on Mental Health Diversion that Crider published early this year, she wrote: “Overworked public defenders, stringent eligibility criteria, and a lack of resources in rural areas have created a system where access is often determined by geography and luck rather than need.”

“Hopeful Legislation”

Opponents of the Mental Health Diversion program argue that it has lax entry requirements and oversight that have led to public safety concerns. Some critics are calling for reform, such as adding to the list of offenses that automatically exclude defendants and making it harder for defendants to prove that a mental disorder was a significant factor in the crime.

In Latimer’s eyes, however, it’s “hopeful legislation” that embodies the logic of rehabilitation.

“Many people who commit crimes are struggling with mental illness,” Latimer said. “Most people out there are not just criminally minded. Mental health court makes really good sense in the context of the criminal justice system and offers a pathway to a much safer community.”

More graduations, more courtroom applause

That August day Michael graduated, courtroom observers — including friends and family members of defendants — applauded happily when the graduations were announced.

Sometimes, due to good performance, participants — including a young rapper — receive permission from the court to change monthly reviews to once every two months.

The rapper had passed the halfway point and was sharing updates on his life in court: The new semester had started, he was taking four classes, and he was working on music, which he described as “therapeutic.”

“A regular check-in with a kind judge is a crucial piece for people navigating the criminal justice system. Court can be a very terrifying place,” Latimer said.

At one point during the Aug. 5 hearings, Judge Rodriguez asked Devin, a defendant who had just graduated, “What’s your secret? Can you share it with people who will start the program today?”

Devin noted that he had met some challenges and setbacks halfway through the program. “Forgive yourself, do your best, be honest and show up,” he said, to the judge and to other diversion program participants.