Can San Francisco's HIV 'miracle' be replicated?

This article was reported as a project for the California Health Data Journalism Fellowship, a program of the USC Annenberg School of Journalism.

Comparing HIV-prevention efforts in three California counties reveals the complexities involved in trying to stop the spread of HIV and AIDS once and for all.

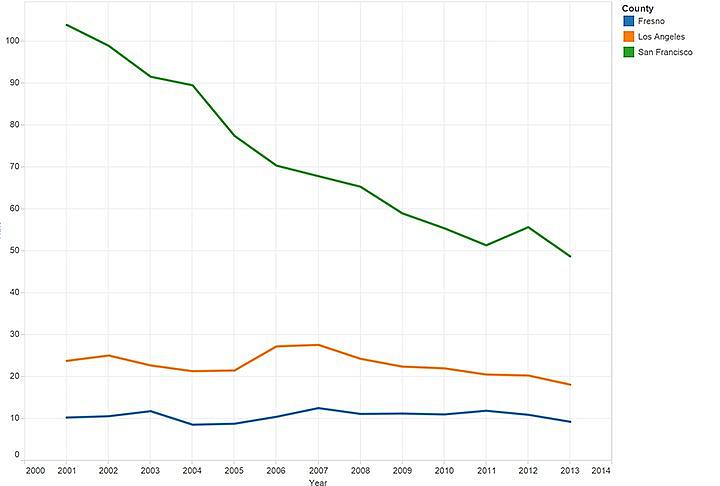

Since The New York Times lauded San Francisco’s remarkable turnaround with HIV — a full two years after The Advocate did so — reporting on the San Francisco "miracle" has become ubiquitous in the media. Rightly so, as the city by the bay saw new infections fall 34 percent between 2012 and 2014 (from 458 to 302). (When not otherwise noted, data in this article is culled from Pertussis Rates 2001-2014, California Based on Infectious Disease Cases by County, Year, and Sex, 2001-2014.)

The San Francisco “Miracle”

San Francisco has arguably achieved their HIV reduction goals through a two-pronged strategy utilizing Treatment as Prevention (getting those with HIV on treatment upon diagnosis, and reducing their viral load to a point where they can no longer pass HIV on to others) and increasing access to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP, the HIV prevention treatment taken in the form of a once-daily pill that’s 99 percent effective when taken as prescribed). But there’s a lot more to the story.

Although the biggest changes occurred recently, San Francisco’s numbers have actually been going dropping for the past decade. That’s not entirely noteworthy, given that rates of new HIV infections have been going down around the world.

In 2013, CBS News reported the “global rate of new HIV infections among adults and children has fallen by 33 percent since 2001.” At the heart of these declines are highly active antiretrovirals, the medications that can not only keep people with HIV well, but also help prevent transmission by controlling viral replication and reducing viral loads, that is the amount of HIV in a person's blood.

But, even in this climate of declining HIV infections, San Francisco’s success stands out. The county is now uniquely positioned to reach their goal of becoming the first in America to end the HIV epidemic in their jurisdiction, a goal dubbed "AIDS-free by 2030" by local activists and policy makers alike.

It’s been a long time coming. San Francisco has been at the heart of the AIDS epidemic since it exploded into public awareness 35 years ago. Considered by some the epicenter for both the swift spread of the disease and the medical response to it, San Francisco’s LGBT community has been actively fighting the epidemic ever since.

A relatively small city, San Francisco is built on a narrow peninsula, sandwiched between the San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean, with houses built upon former wetlands that often climb up the sides of steep hills. The city is also one of the only ones in the U.S. to occupy the exact same borders as the county it’s in. San Francisco city and county both cover around 47 square miles (popular lore calling it 7X7 or 49 miles is off a bit) and it has a population of only 837,442.

But the county hasn’t let its small size prevent it from launching a major assault on the HIV — and it’s been willing to take risks in that direction. Long before the World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention began recommending that all those who were diagnosed with HIV should start on antiretroviral meds as soon as possible, San Francisco had taken that step on its own.

In describing how that decision came about, Jeff Sheehy reveals a lot about how San Francisco works. The gay activist—who made the Out 100 list in 2000 for his work forcing United Airlines to offer domestic partnership benefits — now serves on San Francisco’s Getting to Zero consortium and is director for communications at University of California San Francisco AIDS Research Institute.

The first clinic in the world to begin treatment immediately upon diagnosis was San Francisco General Hospital, at the end of 2009, according to Sheehy. The following year, when it was adopted as county policy, it was still “controversial." They didn't begin immediate treatment knowing that the World Health Organization would later come out showing it would prevent HIV.

"People thought it would," he recalls. "But the reason we did it was those clinicians knew — or strongly believed is a better word — that [immediate treatment] would benefit an individual patient.”

Around that same time, doctors were also beginning to notice increased rates of heart disease among those with HIV, and they were tracing it back to HIV-related inflammation that was gaining a foothold in hard to treat areas like the gut.

“The less inflammation, less organ damage you suffer, which has all been proven by the START study," Sheehy explains. The START (Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment) study showed that the risk of serious illness or major health event was reduced by 53 percent when starting antiretrovirals immediately. "So, it was about the patient care that led us to make this innovation, which has played a big role in getting the rate of new infections to come down.”

This patient-first focus is central to much of San Francisco’s effort to control the virus, making it “about people living with HIV, looking at their quality of life, doing everything we can to keep them healthy and with a reasonable lifestyle as long as we can.”

This approach engenders more than goodwill. Since launching the health department program RAPID, San Francisco has been able to get many people into care within 24 hours of testing positive. They are aiming to cut the time down even further, promoting rapid HIV-testing and pushing for same-day treatment for those who test positive. Sheehy calls this a “collapsing of the cascade,” because it reduces the time between steps in the continuum of care, a five-step plan for those with HIV that ranges from diagnosis to viral suppression. With RAPID, “basically as soon you tested positive, you were immediately connected with a doctor and started on medications.”

That turns the usual process on its head: most places get the newly diagnosed people signed up for benefits (especially insurance) and wrap-around-care before sending them to see a doctor. But San Francisco gets people to a doctor and on medication immediately, and only then focuses on social services, mental health care, substance abuse treatment, and insurance. Even with “a substantial population that either has substance abuse or mental health issues or both,” Sheehy says the program has resulted in an 84 percent suppression rate.

That’s how a program that seems to be all about getting HIV-positive people into care is actually a prevention strategy, even though it certainly wasn't billed as such.

“If we’d have gone to the community at that time and said, 'We want you to be on medication so you won’t infect people,' I don’t know how that would have gone over,” Sheehy says.

Getting people diagnosed and into care is only half the battle. Keeping HIV-positive people in treatment is an essential element in helping them reach viral suppression, and thus become less likely to transmit the virus to someone else.

“We have a big retention initiative,” explains Dr. Susan Buchbinder, director of Bridge HIV at the San Francisco Department of Public Health and a clinical professor of medicine, epidemiology, and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

A $1 million donation from the MAC AIDS Fund is funding retention navigators for clinics in the city that reach underserved populations, especially transgender people, youth, and people of color. If a person with HIV falls off the grid, a retention navigator will go find them and figure out what their barriers to care are, whether that person is in San Francisco or not.

San Francisco Department of Public Health has also recently launched a Centers for Disease Control-funded “data-to-care” program.

Using the Power of Data

Health departments across the country collect data on people living with sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, noting the numbers of people currently living with HIV, those diagnosed with stage three HIV (otherwise known as AIDS), and newly diagnosed HIV cases. Within those groups, most locales break their statistics down by race, age, gender, and mode of transmission.

“Laboratories and providers are required to report to us in the health department any positive lab tests," says Susan Philip, who runs the CDC-funded project, Project PriDE, for the San Francisco Department of Health. "Any tests that are positive for HIV, and any HIV viral loads, we get that information.”

But few jurisdictions are employing their data collection quite the way San Francisco is. In addition to Buchbinder, the county hires a slew of other epidemiologists and statisticians to monitor and interpret the results of their HIV surveillance. And while most counties might just “file it away and maybe make an annual report,” Philip says, San Francisco is translating those numbers into directions for how to best focus the department’s HIV prevention efforts.

“I completely embrace this idea that those surveillance data can be utilized — and should be utilized —for public health improvement,” she adds, and one improvement is finding people who’ve fallen out of care. "If they're in San Francisco and they have... other challenges to staying in care or haven't found the right place for care, or have other priorities in their lives, this is a chance for us to try to re-engage with them.”

Epidemiologists fix a person’s case to their location at diagnosis, so San Francisco continues to track and “own” HIV cases that began there, even when those people move to other cities or states.

“Once they get diagnosed here they remain our cases for the rest of their lives,” Buchbinder explains. “So one of the challenges in trying to figure out what percentage of people are virally suppressed is that some people look like they're not in care and it's just because they've moved."

Philip adds, “We want to make sure people are in care somewhere."

Buchbinder says the department has gotten "pretty good at tracking people down." That sometimes means they've found a San Francisco case but that person isn't virally suppressed — maybe even because they're living elsewhere — but, in data reports, that person counts against San Francisco's record of success.

According to the County of San Francisco HIV Epidemiology Annual Report 2014, of those people who were residents at diagnosis and are still alive, 28 percent “were known to have moved out of San Francisco.” The report also showed in-migration: people living with HIV drawn to the San Francisco Bay Area to access its world-renown HIV services. They create a growing burden on the local healthcare system without adding to the area’s reported HIV or AIDS caseload — and thus funding for the extra care needed — because these individuals were first diagnosed elsewhere. San Francisco’s Epidemiology Unit found that between 2008 and 2010, at least 1,221 people living with HIV who were first diagnosed elsewhere move to the city. An additional 1,000 out-of-region people with HIV received care in San Francsico, but were not counted because of missing HIV test documentation.

HIV Rates in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Fresno (per 10,000 people)

Of course, people with HIV aren’t the only ones drawn to San Francisco. Its reputation as a tech-savvy, ultra-liberal, LGBT-friendly place to live, and its proximity to Silicon Valley have made it the preferred destination of many, including a boom of affluent tech workers, whose hefty paychecks have driven San Francisco’s notoriously tight housing market (historically at 98 percent occupancy) into the stratosphere and pushing the people with fewer resources out of the city — or out of the San Francsico Bay Area entirely. Those displaced are more likely to be younger, black or Latino, or — like many of the inhabitants of the once-gritty, now trendy Tenderloin — poor, homeless, drug users, sex workers, and/or transgender.

Many of those exiled populations also happen to have higher risks of becoming HIV-positive, so their absence may help drive down San Francisco's new infection rates.

According to the U.S. Census, between 2010 and 2014, San Francisco demographics became whiter (rising from 49 to 54 percent of the population) and the percent of Asian-Americans also increased (from 33 to 35). The latter helps explain why San Francisco’s HIV demographics have begun to reflect increases in the number of HIV-positive Asian-Americans.

“There's no question that the demographics of San Francisco are changing,” acknowledges Buchbinder, which “could certainly affect the new diagnoses, because if we get fewer of a certain group living in San Francisco then we see fewer diagnoses in that group. But we can't say that that’s really what accounts for the numbers. We can't say that definitively.”

As Buchbinder suggests, interpreting data is tricky — even a county like San Francisco needs a squad of highly skilled epidemiologists and statisticians, because "none of us can do all the analyses on our own.”

And, although San Francisco handles hundreds of new HIV cases a year, Buchbinder argues that most of the fluctuations in HIV rates over the past five years are simply not “significantly statistically different. The estimated number of new infections have remained relatively stable since 2007. There were fluctuations but…these small increases and small decreases often don't mean much.”

Meanwhile, in small counties, “some of the data…need to be interpreted with caution due to the small numbers,” notes Matt Geltmaker, the public health clinical services manager for San Mateo County Health System (a smaller, partially rural county just south of San Francisco).

“For example," he says, "just one case can change a percentage by two percent either way.” The poor, partially rural Fresno County hovers around 100 new cases a year, so adding 10 new cases of HIV can alter their HIV rate per capita the equivalent of seven times as many people in Los Angeles would.

It All Starts With a Test

When it comes to HIV, testing occupies a unique location at the center of intersecting needs: it can be a tool for prevention, a significant line item in many public health budgets, and a critical window for jurisdictions to monitor the scope of their local epidemic.

Testing is a necessary component of prevention efforts because when people learn they are infected, research shows that most people take steps to protect their own health and prevent HIV transmission to others.

Regardless of whether the next move is “getting people linked to care if they test positive or getting them on PrEP if they test negative,” Philip adds, “testing is the underlying initial, necessary step.”

Acording to the 2007 and 2008 California Publicly-Funded HIV Counseling and Testing Data, the state routinely conducted over 130,000 HIV tests annually. That is until the recession-based decision by lawmakers in 2009 to plunder the state’s Office of AIDS, cutting its budget in half, and completely decimating the department’s prevention funding.

“The amount of testing before, versus after the budget cuts was roughly cut in about half — the number of tests done annually was cut in half,” confirms Karen E. Mark, MD, PhD, who has led the California Office of AIDS since 2010. To “partially mitigate” the impact, Mark says OA began limiting its testing to higher risk targets. “While we still diagnose fewer people with HIV than we did before the budget cuts…the new amount — of new diagnoses — was not cut in half. Because we're testing people at higher risk. [Even with a lower] number of tests we're diagnosing more people.”

In addition, Mark says, “We have been doing a lot of work over the last many years to increase routine testing in medical settings,” where Mark says, “the majority of new diagnoses are actually made,” and the only place “people who are not in sort of a high risk group are going to be tested for HIV.”

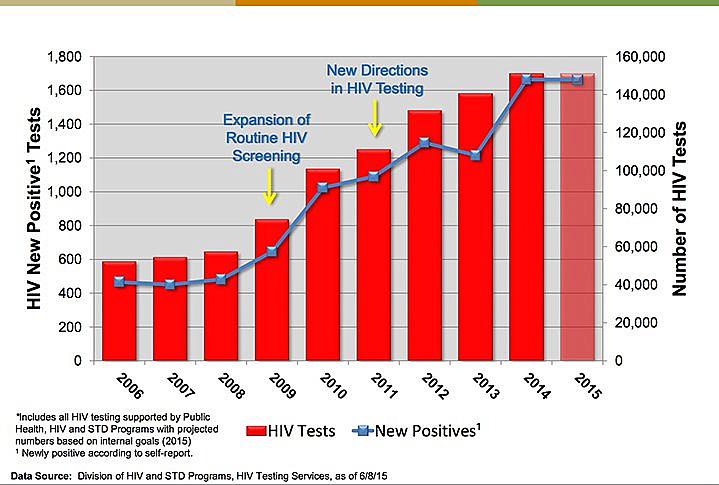

Los Angeles County Public Health Division of HIV and STD Programs'. HIV Tests and New Positive Diagnosis by Year.

Kyle Baker, from the L.A. County Health Department's Los Angeles Division of HIV and STD Programs, calls routine medical testing an idea that “sounds terrific on paper, but when it gets down to educating folks in clinics, thinking through their workflow and staffing patterns and things like that, on-the-ground experience has shown that it’s not as simple as it once seemed.”

The L.A. County Health department has had trouble convincing independent institutions — and even facilities that the county funds — to adopt routine testing. One L.A. County hospital now has a “robust program,” Baker says. "There were still years of working and negotiating with the hospital administration — there's a lot of barriers there.”

After the state budget cuts, Los Angeles (like San Francisco) “made the decision that we were not in any way going to decrease by one test the amount of testing that we fund,” says Baker. “We refused to cut testing.”

Indeed, both jurisdictions have actually increased testing in recent years. In Los Angeles, those increases have been mirrored by a rising number of new HIV cases. Generally there are marginally more HIV tests given than there are new positive diagnoses, but the 2014-2015 tests vs. new HIV diagnosis appear to be neck to neck (although numbers can still change several years later as data improves).

“But is this merely a classic case of testing finally catching up to reality? Some data experts point to cancer screening data, in which incidences appear to soar but it's generally thought to be because of new testing methods uncovering older cases, not a rise in cancer diagnoses. At some point, some experts say, as protocols improve and enough tests are done, the rate of new cases will flatten so experts can get a true read on new incidents.

Philip agrees that today’s tests may be reflecting another year’s infections. “I can be diagnosed with HIV this year but have gotten infected many years ago. We think that that is getting to be less and less likely because…people are testing quite often. We start out from that advantage of having a really testing culture [in San Francisco].”

Indeed, it's estimated that 93 percent of San Francisco’s HIV-positive residents knew their serostatus in 2013, according to the Department of Public Health's 2014 HIV Epidemiology Report.

Things were different in Fresno County, where, after the state budget was disemboweled, “the amount of HIV testing just was cut dramatically,” says Jena Adams, who is part of the HIV/AIDS team at the Fresno County Department of Public Health. Since the budget cuts, the county has implemented rapid testing and is trying to focus testing on high risk populations, including current and former partners of those who’ve been diagnosed with HIV.

“Now, our testing numbers are not what they were back in 2009," Adams admits, "but we're increasing the number of new confirmed positives that we're locating, and we're getting them linked into care in a shorter period of time.”

How that has impacted the rate of new HIV cases found in the county are hard to say. Perhaps if Fresno (or other poorly-funded counties) don't test aggressively, they will get behind the curve of prevention and treatment — or are already there.

One would expect the new cases to go down when testing rates were cut, but instead Fresno’s rates continued to climb (except for rates among black women, which plummeted after 2009, part of a national trend). It’s also worth noting that the rate of people diagnosed with HIV and AIDS simultaneously, or within that same calendar year,rose sharply in 2009 after testing was cut. Though those late-stage diagnoses have declined recently, they have yet to return to pre-funding levels.

Looking at the data, confirms that the state’s new HIV cases were not cut in half following the funding decimation. That could mean, as Mark suggests, that testing is now more efficient and targeted, so most cases are still being caught. But it could also indicate a rise in the number of overall new HIV infections, being masked by the drop in testing. Altering the way surveillance is collected always impacts the end results — and the reports (and funding) based on those results.

HIV Prevention: From Condoms and Beyond

In the pre-PrEP world, even five years ago, if you asked most people about HIV prevention, they would probably point to condoms. And they wouldn’t be wrong. San Francisco may be peppered with beautiful Victorian houses, but it has never been hampered by a prudish, Victorian-era aversion to sex. Condom distribution has been a part of San Francisco’s prevention efforts from the very beginning, supported by agencies, organizations, and business (from bars and restaurants to retail stores and bathhouses) as well as individuals who’ve passed out condoms by the millions in the decades since the AIDS epidemic began. Even today, most recognize the power a thin sheath of silicone can have in protecting public health, which is why, in February of this year, the San Francisco Board of Education voted unanimously to allow access to condoms in the county’s middle schools. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, “The new policy will allow staff to individually give students condoms ‘in conjunction with a session with a school nurse or social worker to identify risk factors and provide referrals or resources as necessary.’”

It’s something Buchbinder couldn’t be happier with especially because, she says, “parents aren't going to be able to opt out of it! So the students can go and get the services that they need. Because often it’s the people who won't talk to their parents that need services the most.”

Unfortunately, although condoms have long been the go-to for HIV prevention, a recent report, published in the journal AIDS, shows condom use among gay and bisexual men has been dropping for a decade, and in 2014, the number of HIV-negative gay and bisexual men who reported having sex without a condom rose to 41 percent.

Condoms and PrEP may be the pillars of today’s most successful HIV prevention campaign, but they are just the tip of the iceberg. there’s actually a wide range of strategies that can be employed. (Including some unpopular options like male circumcision and increasing the taxes on alcohol.)

You won’t see many San Franciscans coming out on the side of circumcision, but the county health department employs a broad range of prevention tools. They’ve developed partnerships with key stakeholders, pushed RAPID into high gear, embraced harm reduction efforts like needle exchanges, and developed data-to-care programs. They connect with the current and former partners of the newly diagnosed person, get them in for an HIV test, and then either into HIV treatment if they are positive or on PrEP if negative.

The Biomedical HIV Prevention Option

You can’t talk about San Francisco’s prevention success without talking about PrEP, because the use of Truvada (the only treatment currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration to prevent HIV) plays a central role in the sharp decline of new infections in San Francisco county. As the site for one of the largest PrEP studies in the country and home to early adopters (not just patients but also doctors and policy makers), San Francisco has some of the highest rates of PrEP use in the nation.

Still, PrEP remains fairly new, stigmatized, and relatively expensive, so ramping up PrEP access — especially for underserved populations — and reaching widespread adoption, could continue for years, even in San Francisco. Currently, nationwide, less than five percent of men who have sex with men have tried PrEP.

“We still haven’t been able to deliver [PrEP] — at least in my mind — to the transgender community or to the Latino [or] Spanish-speaking community,” says Sheehy. “Because the information on this has been in all English language, and all in the gay community…it’s [also] very frustrating that [PrEP is] not being delivered to women with the same sort of aggressiveness that it’s being delivered to men.”

Philip, who runs Project PriDE in San Francisco, says its goal is to make sure that health inequities around HIV are addressed, and "PrEP is one way of doing that.”

To improve access to PrEP, PriDE is recruiting community leaders help create targeted messaging about the benefits of PrEP, Philip says. She hopes this will foster a two-way communication, so the Health Department can better understand “the barriers that people might be experiencing. It really takes having someone who is an expert — and not an external expert, but a person who has a lived experience…to inform [us] how best to improve health for people who've been in similar situations.”

PriDE and several other programs also provide PrEP navigators, a step Buchbinder considers critical "because people don't know how to get PrEP, and how much it's going to cost them, and which insurance plan they need.”

The county is also expecting to see trans people’s access to PrEP escalate in the coming years with programs from Project Inform and the ambitious, first-of-its-kind, $9.4 million study by the California HIV/AIDS Research Program that is recruiting 700 trans people (in San Francisco, L.A. and several other California locations) to evaluate whether PrEP is useful for transgender people.

Other jurisdictions in the state, including Los Angeles, are eager to replicate San Francisco’s success with PrEP; they just haven’t gotten there yet. Still, people like Baker don’t deny that the impact of PrEP on the world of HIV prevention is huge.

“It's night and day since then," Baker says. "It's affected it very significantly and we think in a very positive way.”

Los Angeles May Have Different Issues

The 4,084 square miles of Los Angeles County could easily engulf 87 San Franciscos — and it does, in fact, envelope 88 cities and a 100 unincorporated locales. It is home to over 10 million residents, and the county of Los Angeles actually has a population greaterthan that of 43 of America’s 50 states. The mega-county’s enormous population (equal toWashington, D.C., Houston, San Francisco, New York City, and Philadelphia combined) represent extreme demographic, socioeconomic, cultural, and linguistic diversities.

According to the Los Angeles County HIV Cascades and PLWH Estimate Division report completed in May 2016, L.A. County is now home to an estimated 58,503 people living with HIV, including 12 percent of whom are estimated to be unaware of their status. The county’s burden of HIV and AIDS is magnified by the sheer numbers of people living with HIV co-morbidities, in poverty, and without health insurance.

Despite the relative wealth of the state, a 2014 KPCC report on the American Community Survey from the U.S. Census Bureau revealed that the poverty rate is higher in Los Angeles County than in the rest of the California — and the nation as a whole — with 18 percent living below the poverty line.

L.A. is known as the city where “there’s no there, there,” a reference to its sprawling nature and absence of a true municipal core. Public transportation is still lacking, and the car culture has led to extremely heavy traffic, making it even less likely a small team could traverse the county in a timely fashion, the way RAPID can in San Francisco.

According to the Los Angeles County Five-Year Comprehensive HIV Plan 2013-2017, L.A. County "has the second largest HIV-positive population among local jurisdictions in the nation.”

From 2010 to 2013, the number of persons annually diagnosed with HIV in L.A. County decreased nearly 16 percent from 2,161 to 1,820. A total of 943 Stage 3 (or AIDS) diagnoses were reported in 2013; 29 percent of those were diagnosed as Stage 3 less than one month after they learned they had HIV. The L.A. County 2014 Annual HIV/STD Surveillance Report indicates that an estimated 79 percent of all persons with HIV were linked to care within three months of diagnosis, 61 percent were engaged in care, 51 percent were retained in care, and 50 percent were virally suppressed.

According to U.S. Census Bureau estimates, Latinos represent 48 percent of the population of Los Angeles, while African-Americans represent only 9 percent, but blacks are still disproportionately more likely to become HIV positive. In 2015 the L.A. Daily News reported that “despite enrolling half a million people in health insurance under the Affordable Care Act…Los Angeles County still has more uninsured residents than all but five states.” The report, based on newly released census and data analysis by the Center for Health Reporting, revealed that Los Angeles County is home to 1.55 million uninsured people, 69 percent who are Latino, and 46 percent who are not U.S. citizens. These uninsured rely on the county and its network of community clinics if they become ill, including if they become HIV-positive.

Some aspects of L.A.’s HIV risks are unique. For example, in Los Angeles HIV aquired through shared needles tend to be less about injection drug use than about gender expression and/or unlicensed medical providers. Transgender residents may share hormones or feminizing injectables, while some pop-up health clinics may also offer injections of vitamins, flu shots, or antibiotics but fail to consistently exchange syringes with sterile ones.

In 2011, the CDC complained that despite an estimated 18,800 people living with HIV who are aware of their HIV infection but not in care, L.A. County's system of care has "never conducted focused outreach to this population.” It has also been slow to embrace PrEP. When county supervisors announced the county’s first PrEP program last June, LA Times, quipped, “Until this week, Los Angeles County hadn't begun to spread the word and distribute the medicine despite being the second-largest epicenter of HIV and AIDS in the country. That's partly because county health officials were unsure they would get the necessary support to provide the drug, which has been somewhat controversial, said Supervisor Sheila Kuehl."

The Supervisors’ call for the county's Division of HIV and STD Programs to “ramp up our biomedical intervention programming,” Baker says, includes “specifically PrEP — but also PEP — and to do so in a way that would provide access to meds [but] may not be in the form also of providing meds directly.”

A year later, and L.A. County is only now “about to finalize” contracts with a number of local HIV service organizations, who will then provide PrEP information and connect those who are interested with patient assistant programs, insurance, or other ways to pay.Timed to correspond with the launching of the PrEP navigation program, the county is “rolling out our PrEP social marketing campaign,” says Baker. “It's going to be quite robust…bigger than anything we've done in quite some time.”

One area L.A. has taken a lead in is their use of geographical information systems to collect data and pinpoint services. Baker explains that the HIV division has invested in their “ability to use geospatial analysis and data collection in order to really best identify where the disease burden is located and, therefore, where potential new infections are likeliest to occur. We feel very strongly that that investment has paid off. We have a team here who's very adept at the geospatial analysis and producing a lot of really important maps and data to support our planning efforts.”

Overall, Baker says, L.A. County has dramatically improved how, in 2016, "we go about our HIV prevention work — that's so different than we did even 10 years ago — folding in biomedical interventions, focusing on testing and case identification, and outreach linkage, retention activities."

But Back in Fresno

Fresno is a world away from San Francisco and Los Angeles, and here, the epidemic actually looks worse than it did a decade ago.

Fresno County is located in the middle of California’s broad San Joaquin Valley (the portion of the Central Valley that lies south of Sacramento). It’s a flat, fertile strip of land that California water projects transformed into the nation’s salad bowl; Fresno is the number-one agricultural producing county in the U.S. The agricultural heartland has long relied on a workforce of immigrant laborers — including many migrant workers in the country without documentation. Today, immigrants make up 22 percent of Fresno County's population. According to the University of Southern California Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration, 37 percent of Latino immigrant adults in Fresno County are without documentation, making them more vulnerable to lower wages, labor abuses, and other causes of "social instability."

USC's immigration fact sheet notes that 80 percent of those who immigrated to the county arrived in the U.S. after 1980, and almost a quarter immigrated in the past decade. The majority (66 percent) of Fresno's immigrant population were born in Mexico. Forty-two percent of Fresno County’s children have at least one immigrant parent; 70 percent of resident adult Latinos without documentation are living with a citizen (for 41 percent that citizen is their own child).

Language barriers also isolate these immigrants: 34 percent of those have no one in the home over 13 years old who speaks English fluently.

In 2011, Fresno County’s new cases of HIV spiked 73 percent over the previous five-year average. For nearly a decade, the county has been struggling with an explosion of injection drug use under conditions much like those that sparked the rural HIV outbreak in Indiana. Those using injection drugs are at an especially high risk for getting HIV, but often have trouble accessing services that prevent HIV, such as mental health care, PrEP, and clean needles. Despite California’s needle exchange law, studies show access remains limited.

According to the the county's Fresno At a Glance HIV/AIDS 2014 fact sheet, 55 percent of the new HIV cases were among Latinos, which is still higher than their representation in the county’s broader demographics, where they are just over half of the population. Across the nation, the HIV diagnosis rate for Latinos remains nearly three times higher than that of non-Hispanic whites, and Latino men have six times higher rates than Latina women, according to an October 2015 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Unfortunately, instead of declining, new HIV diagnoses among Latino men who have sex with men, spiked in the 15 years between 2008 and 2013.

Meanwhile, in 2015, Diana Aguilera reported on Valley Public Radio of Fresno (KVPR), “The county estimates young people ages 15-24 make up roughly 20 percent of all HIV infections.”

It’s where these statistics intersect that has the highest burden: “The majority of the new cases that we're seeing are among young men of color who predominantly identify as gay or bisexual,” acknowledges Adams, the Fresno health department official. “I think that there's just not enough education out there…and because there's not a lot of conversation about HIV, there's no fear of HIV anymore. Young people…don't talk about prevention. What you normally hear is, ‘If I get it, I can just take a pill. It's only a pill a day.’”

According to the California Integrated HIV Surveillance, Prevention, and Care Plan of 2013, immigrant populations in the state are more likely to be simultaneously diagnosed with HIV, AIDS, and concurrent opportunistic infections. Limited access to health care, lack of knowledge regarding risk, social stigma, secrecy, and symptom-driven health care seeking behavior all contribute to this population having higher rates of disease progression at first diagnosis.

In 2009, the state cut the Office of AIDS budget by more than $80 million dollars. In the world of trickle down HIV bugeting, dozens of OA-funded public health departments and community organizations alike were forced to eliminate programs or even close their doors.

In Fresno, The Living Room, which Aguilera describes as “the longest standing HIV and AIDS social support center in the county” was forced to eliminate numerous positions and drop from serving 400 people a month to 50.

“The funding cuts [also] affected our program,” says Adams. “In June of 2010, the health department saw the closure of our STD clinic. We always had HIV test counselors assigned to the clinic Monday through Friday and the clinicians would offer clients that came in for STD checkups, they would offer to do a blood draw for HIV testing at the same time. In addition, we had people that were coming in just specifically for HIV and we, of course, tried to transition them to STD services as well. So it [had been] a win-win for our programs.” No more.

After they "lost" the clinic, HIV testing was hit hard. But the bigger problem is the fact that people in the county aren't getting in, and staying in, care. Less than half of all the people living with HIV in Fresno County are in care and have the virus under control, which means far fewer people are in treatment and supressed enough to keep the virus from being transmitted.

Instead, Fresno’s 2013 Annual Communicable Diseases Report reveals that more than 1 in 4 (or 27 percent) of all new HIV cases were diagnosed with HIV and AIDS at the same time. Another 9 percent were diagnosed with AIDS soon after first diagnosis. That means over a third (in fact 36 percent) of peple with HIV in Fresno County were first screened after their disease had already progressed, making it far more difficult for those people to acheive viral suppression, especially to undetectable levels.

That Fresno is also far behind jurisdictions like San Francisco and L.A. when it comes to PrEP, is another frustration for Adams.

“We are hearing more young people ask about PrEP," she says. "In Fresno County, it's a challenge for people to get PrEP, especially for young people who are not working full time, don’t have insurance. We have a few providers who are offering PrEP, but no one who is accepting Medi-Cal. That's huge, because the majority of the young people that are testing positive qualify for Medi-Cal.”

Aware that African-Americans carry a disproportionately high rate of HIV in her county, Adams wonders, “What can we do to reduce the incidence among African-Americans? I think because the population is so small, there's a stigma, especially for African-American men, MSM, for getting tested. When we do test them, again, like the other young men of color, we get them linked into care, they may make that first appointment, but they don't stay.”

Although the number of Asian-Americans with HIV in Fresno is very small, the number of new cases in that community jumped from under ten cases in 2011 to over 20 in 2012.

“We can't keep focusing our messages on talking about the Hispanic and African-American populations,” Adams says. “We must be inclusive and mention — even if it's just small numbers — what we are seeing in the Asian population as well.”

Struggling with how to get more people of color to do HIV testing, Adams longs for some of the programs other jurisdictions, like Sacramento’s Golden Rule Services, that employs peer advocates.

“They have young men of color — Hispanic and African-American — that are outreach workers and they're doing presentations, they're testing at bars. That's fantastic. I would love to see something like that in Fresno, but in that respect, we are still rural and just, I think, too small.”

The fact that it's a rural county also hampers efforts to prevent and treat the virus in Fresno. And there's the impact of stigma, where people are too ashamed to even be seen going to the places where HIV testing and prevention services are provided.

“In a small town, when you do get tested, or when you want to be tested, do you want to be tested there? Because walking in the door of the clinic is your cousin or your aunt. We do have some clinics opening in some of our smaller communities that are willing to offer HIV services so clients don't have to worry about trying to come into Fresno for medical services. Once they've tested positive, they can stay in their area. But we need more of that.”

Adams says if someone in the city of Fresno tests positive, she could conceivably get them “in their first medical appointment for their HIV diagnosis within a week to two weeks of diagnosis” compared with the 24 to 48 hours it takes in San Francisco.

“Now, if someone tests positive that lives outside of the city of Fresno, say in Coalinga or in Firebaugh or Kerman — in these rural areas where transportation is a problem," Adams continues, "and if the client doesn't have transportation, they have to rely on public transportation, which may mean only one bus in the morning and then one bus later in the afternoon.”

For many people who need testing, but must rely on a whole day just to get a test, that means a loss of income.

“You can't work that day," Adams says. "Whatever your job is, whether you're working in the agriculture industry or not, if you have a job where you don't accrue time off or sick leave, then that's loss of pay; that's a day's pay gone.”

She's wistful about San Francisco too. “I keep thinking about that RAPID system, because I want that. But we just don't have all the infrastructure that San Francisco has to be able to adopt a program like that at this time.”

Exporting the San Francisco Model?

As the examples of San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Fresno reiterate: there’s not just one HIV epidemic. There are differences in race, income, class, and more behind the epidemic that makes it such a multi-headed beast.

For example, Los Angeles has over 600 trans people, mostly women, living with HIV (according to Los Angeles County Department of Public Health 2014 Annual HIV/STD Surveillance Report), while in Fresno, Adams says “I couldn't even tell you the last time I've been made aware of a new transgender positive.”

Simultaneous HIV and AIDS diagnoses are shockingly common in Fresno, but only 18 percent of San Francisco’s new cases “develop AIDS within the first three months of their HIV-positive diagnosis,” according to Buchbinder.

Regardless of how different the epidemic might be in other locales, many people believe San Francisco County’s model can work elsewhere.

Philip acknowledges that “San Francisco's gotten where it is…because there were very dedicated, smart people at the community level. Individuals and others who were impacted by HIV/AIDS and have a lifelong commitment to activism and to really demanding more from the Health Department, from all of us who are working in the area of sexual health and HIV/AIDS and general health.”

But she believes similar people exist in other jurisdictions as well and, she says, “that kind of advocacy is not to be feared. I think it's to be embraced. It might feel a little uncomfortable…but it really becomes critical.”

While it might seem that San Francisco’s method of eliciting community engagement could slow down the process, Philip says some of this is old hat for those in California, where community planning councils are already “making sure that public health is always mindful of the voice of the consumer of HIV services and always mindful of the voices and the needs of people who are at risk for HIV as well as living with HIV.”

The CDC HIV Planning Guidance of 2012 offered advice on using “scientifically proven, cost-effective, and scalable interventions targeted to populations in geographic areas most affected by the epidemic,” including involving key stakeholders and addressing “social determinants of health associated with but not limited to HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted diseases, infectious diseases, substance abuse, and mental health.”

Two of the core elements to the San Francisco model are PrEP and TasP, both of which Fresno is still far from seeing the benefits of. But Sheehy still thinks they make the San Francisco model's adoption elsewhere a possibility.

“Introducing PrEP into a healthcare system? With Obamacare that’s possible,” he says. “And certainly in California, where Medicaid covers PrEP, it’s possible to deliver PrEP widely across a number of populations.”

But he concedes, “a network of sexual health clinics [might need to] be developed within communities, especially communities that have had trouble accessing healthcare on a regular basis.”

It's also important to remember that San Francisco — despite all of its funding, civic commitment, and access to PrEP — is still experimenting with methods to reach underserved communities. Those who follow San Francisco may get the benefit of their experience, but to-date, much of that experience is with reaching a specific segment of the population, largely white men who have sex with men. Because other counties don't have the demographics San Francisco does, they would need to adjust programs to account for those differences. And that may not be easy — especially without additional funding.

In 2004, the RAND corporation created Maximizing the Benefit: HIV Prevention Planning Based on Cost-Effectiveness A Practical Tool for Community Planning Groups and Health Departments. The CDC-funded project provides a spreadsheet designed to help organizations and health departments estimate the relative cost-effectiveness of various HIV-prevention strategies. Although this tool was created nearly a decade ago, and before the true value (and cost) of PrEP was known, its mathematical equations and underlying principles remain valid.

In Maximizing Benefits, RAND notes that exporting a successful HIV prevention strategy from one location to another is often less effective than assumed, “Even when a well-designed study has demonstrated that an intervention is effective, you should not assume that this intervention could be implemented successfully elsewhere. Something that works for gay men in New York may not be feasible in a more politically conservative city.” Likewise, “if an intervention was found to be effective using 100 subjects, it may not be the case that it will be effective using 1,000, 10,000, or even 20 subjects. The logistics of the interventions change with number of people in the target group. As such, the actual dynamics of the intervention may change and it may no longer be effective. Programs found to be cost-effective in controlled intervention trials often prove to be less effective when replicated on a larger scale or targeted to a different audience.”

Sheehy certainly recognizes some of the barriers to wide scale adoption of the San Francisco model. While he believes, “PrEP can be delivered widely in California,” he adds, “but I really do think you have barriers if you get to places where you don’t have Medicaid expansion and the expanded Medicaid and Medicaid as a whole doesn’t cover the cost of PrEP.”

As Los Angeles and Fresno demonstrate, San Francisco programs like RAPID, remain the envy of other health departments, but they too can be difficult to replicate in other locations. Whether it's Fresno's rural communities or L.A.'s gnarled traffic patterns, barriers remain for establishing similar programs. In addition to money and a blueprint for prevention, Sheehy believes another element is essential for a jurisdiction to duplicate San Francisco's sucess: “These models can be [there],” he says “But then you need the political will to deploy them.”

While San Francisco is undeniably on target to meet their goal of Getting to Zero, Los Angeles is struggling to keep up, and Fresno is barely in the game. The reasons are many, but Adams hits one squarely on the head: because of their 35 years in this fight, San Francisco now has the infrastructure in place to have a real chance at ending this epidemic in their county. That may be far more difficult to replicate than a pro-PrEP philosophy, patient-focused but rapid medical care, a testing culture, the political will, and the funding to pay for it all.

[This story was originally published by Plus Magazine.]