Chasing the Fix: Peer support for people living on the street

The story was originally published in The Public's Radio with the support from USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 National Fellowship.

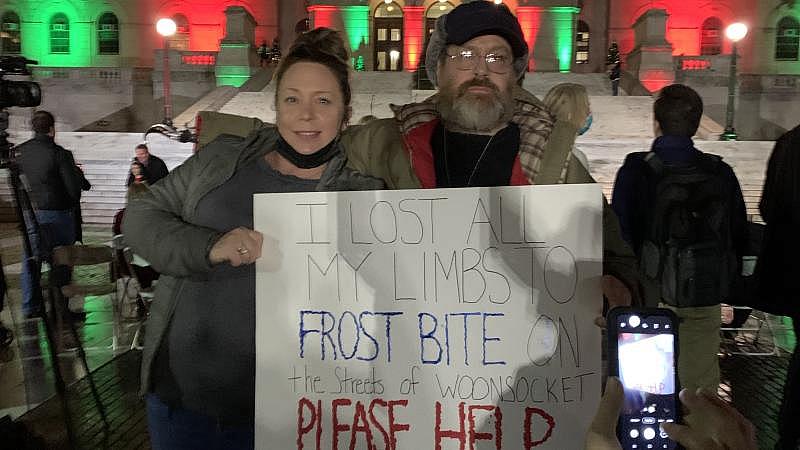

Doctors had to amputate Bill's hands and feet after he fell asleep in the snow when he was homeless in February of 2018.

LYNN ARDITI/THE PUBLIC'S RADIO

“I'm an alcoholic. I was homeless for almost 12 years.”

Doctors had to amputate Bill's hands and feet after he fell asleep in the snow when he was homeless in February of 2018. LYNN ARDITI/THE PUBLIC'S RADIO

“I became, well, really homeless homeless when my mom died.”

“Society knows you're out there but they don't acknowledge you.”

“I started feeling like this is what my life was gonna be like for the rest of my life, just being on the streets and stuff.’’

Bill, June, Richard and Mike, were speaking during a meeting last September of their peer recovery group. (We’re using their first names, to protect their privacy.)

Nearly a decade ago, they lived together in a tent encampment in the woods behind a strip mall in Woonsocket, R.I. Now, some of them say they might not be alive if it weren't for a tenacious social worker and this support group that didn’t require a pledge of sobriety.

Click here for more stories from Chasing The Fix

The Public's Radio · Chasing the Fix: Peer support for people living on the street

Leading the group’s 13 participants that afternoon in a park in Woonsocket was Tammy Zerrenner, a social worker at Thundermist Health Center.

“Today is a celebration, and today is honoring those of us who did not make it,’’

Zerrenner said. “I want you guys to tell each other, remind each other what you've been through, living on the streets (and) how things have changed for you.’’

Tammy Zerrenner of Thundermist Health Center in 2016 when she was leading a recovery group in Woonsocket. COURTESY OF TAMMY ZERRENNER

Zerrenner is trained in a form of addiction treatment called SMART Recovery, which uses cognitive behavioral therapy and positive thinking to help people beat their drug habit. SMART Recovery supports the use of medication assisted treatment. And unlike Alcoholics Anonymous, the program doesn’t require a pledge of abstinence.

The SMART Recovery program accepts that relapse is part of the recovery process. The approach is backed by a 2019 study that found adults averaged about five recovery attempts before achieving a sustained resolution to their drug or alcohol problems.

“It’s an excellent model,’’ said Patty McCarthy, chief executive officer of Faces & Voices of Recovery, a Washington, D.C.-based national network of recovery groups. And the program is especially important, she said, for people who are experiencing homelessness.

“It’s very difficult to find recovery,” McCarthy said, “if you don’t have a roof over your head.”

Back when Zerrenner started the Woonsocket recovery group in 2014, Thundermist was looking to reduce costly hospital emergency room visits. And she discovered that some of the people who kept showing up in the ER were homeless.

They had no regular medical care, Zerrenner said, and many of the people she met who were living outside were addicted to alcohol or drugs.

“If there was a camp out in the middle of the woods, she would traipse out there and she would go find people,’’ said Gloria Rose, a senior director at Thundermist Health Center. “She would go and try and track them down and offer support and get them enrolled and have them come to group.’’

The people in the encampment were “already somewhat of a family,’’ Zerrenner said, though “they didn’t function as a high-functioning family. But they did take care of each other.”

Their fragile fraternity included people struggling with mental illness as well as substance use disorders. Zerrenner started by inviting them to Thundermist for doughnuts and coffee on Fridays, when there were no free meals in the city.

People came for the breakfasts and stayed for the discussions. And the type of clinician-led group normally attended by people with jobs and cars and appointment calendars became a regular fixture in the lives of those with no permanent address.

“None of them ever thought that they would have housing or income or even have any recovery,’’ Zerrenner said. “So once one person kind of bought into it and got serious about it, and had a year in, then everyone in the group tried.”

Much of the work by Tammy and her colleagues at Thundermist involved helping people in the group navigate the bureaucracy of applying for social security benefits and housing — a process that often took years. Many of her clients had to get off the streets for good, she said, before they could stay sober.

Of the 20 or so members who have joined the group since it started, Zerrenner said, five have died and almost all of the others are in recovery. Four of the original members still attend the weekly meetings or stop by to talk with newer members.

A couple who live in a senior high-rise on a morning walk in WWII Memorial Park in Woonsocket, RI. LYNN ARDITI/THE PUBLIC'S RADIO

Zerrenner, who is now a program director at Thundermist, returned to lead the group that September afternoon in the park. She started by asking the group if anyone wanted to remember any of the original members who had died.

June began to cry. She was remembering her partner who overdosed. He was 52.

“Oh, God, he was a wonderful person,’’ June said. “I miss him so much.”

Alcohol and drugs weren’t the only killers. Winters on the streets could be brutal. One night in 2018, Bill fell asleep in the snow under a bridge.

“At that point in my life I didn't care about anything,’’ he said. “Literally, even my life.”

Bill got such bad frostbite that doctors had to amputate both his hands and feet. He now lives in one of the city’s subsidized apartments. And he gets around in a wheelchair. He said he wishes that he could do more to help his friends who are homeless, but his apartment restricts visitors.

“When my legs are on and they're working properly,” he said, “I'll walk downtown and say hi to everyone. See how they're doing.”

Richard is one of the oldest members of the group, and one who Tammy had worried about.

“I’m a recovering alcoholic,’’ Richard said. “My sobriety date is November 20th of 2016, which puts me at five years and 10 months.”

The group broke out in applause.

A formerly homeless man, Bill, with Amanda Leigh, then of Thundermist Health Center, at a State House protest in 2021. COURTESY OF TAMMY ZERRENNER

For Richard, living on the streets in Woonsocket meant weekly run-ins with the police. “Everything you do out there is illegal,’’ he said. “Open container, sleeping in public, loitering, trespassing…’’

Richard got financial help from the nonprofit Community Care Alliance so that he could rent a room in a sober house. He stayed two years until he got into an apartment.

“First thing I do, I pray in the morning,’’ he said. “I make my bed. I didn't have a bed before.”

Like Richard, Mike also now lives in his own apartment. And he shares it with his fiancé.

“If it weren't for this group,’’ Mike said, “I don't even think I'd be alive right now to be honest.”

Mike joined the recovery group after he nearly died of an overdose. That’s when he realized that he’d been using alcohol and drugs to cope with his mental illness.

“The main reason why I started drinking…and abusing inhalants,’’ he said, “was because I didn't like how I felt inside, you know?”

Like several others in the group, Mike had experienced trauma. And he said that the recovery group gave him the support he needed to work on his mental health.

“Everyone that I know here has helped me in some way or another,’’ Mike said, “helped me basically – excuse my language for this, but get my f****** s*** together. And now, I'm not looking back.”

The group still meets weekly with a clinician trained in SMART Recovery. Many of its newer members are currently homeless.

[This article was originally published by The Public's Radio.]

Click here for more stories from Chasing The Fix

This story was produced with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 National Fellowship.

Health reporter Lynn Arditi can be reached at larditi@thepublicsradio.org. Follow her on Twitter @LynnArditi

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.