Children in Peril, Part 2: 'One suicide is too many'

This story was produced as a project for the 2019 Data Fellowship. Click here to read about her struggle to obtain the death records she needed to document youth suicides.

Her other stories include:

Safety steps in pandemic cloak abuses

Children in Peril: Mental health workers fight rising number of suicides in Arkansas. A young survivor joins the push and talks about her struggles.

Carrie Hill, Aaron O’Quin, Ben Goff, Yutao Chen

Kelsey Bell is alive; she's happy a lot of the time.

The 20-year-old attempted suicide when she was 13 after years of dealing with depression, anxiety and an eating disorder. She says her recovery has highs and lows, but she's stable now -- enough so that she is a junior board member with the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and is majoring in psychology.

"I guess that pain turned into passion," Kelsey said.

Kelsey is part of an intensified effort to stem the rising number of youth suicides in Arkansas.

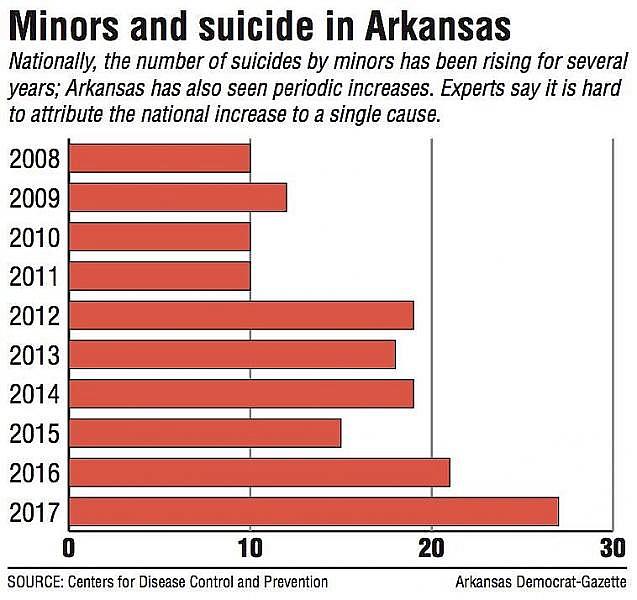

The number of suicides by minors in Arkansas jumped from 10 in 2010 to 27 in 2017, according to recent federal mortality data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nationally, the trend is similar among other age groups.

Suicide became the second-leading cause of death in people ages 15 to 24 nationally in 2017, according to the CDC. Automobile crashes are the leading cause.

The numbers have increased as well for children ages 10-14, according to the CDC.

Experts who work in suicide prevention, research and mental health advocacy weren't able to identify the reason behind the trend. There are many possible explanations and more research is needed, particularly for the younger population, they said.

"In the suicide prevention field, we're all grappling with why is it just this sudden -- in the last couple of years, we've just seen this huge increase. And I don't think we really have a grasp on suicide specifically other than there are a lot of factors," said Hope Mullins, the assistant director of the Injury Prevention Center at Arkansas Children's Hospital.

From 2012 to 2017, at least one child in most Arkansas counties died by suicide, according to an analysis of data compiled by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette from available public records.

The oldest was just a few months away from his 18th birthday, and the youngest was about to turn 6, the newspaper's data shows.

This story is one of an occasional series about what the newspaper's data shows regarding child fatalities in Arkansas. A previous article examined child deaths from guns. Others will look into suffocation and other unnatural, often preventable causes of child fatalities.

Documents gathered by the newspaper show 63 reports of suicide -- 21 by girls and 42 by boys -- in the 2012-2017 period.

All but 13 were teenagers.

Some death reports obtained through the state's public records law listed histories of mental health problems or major life changes such as breakups, deaths in their families or sudden moves in the children's lives. Others listed no such history.

But the reports used by the newspaper are incomplete, as shown when comparing the Democrat-Gazette's database with federal mortality data.

Federal data shows that 119 children died by suicide in Arkansas from 2012 to 2017, an average rate of 2.8 per 100,000 children. Arkansas' rate ranked 13th in the nation during that period, the most recent for which data was available as this article was being reported.

While many death reports used in the newspaper's analysis lacked information on race, CDC data shows that 104 white children died by suicide in Arkansas from 2012-2017. Fourteen black children died by suicide in the same time period.

The CDC's 2018 death statistics, which came too late to be included in the Democrat-Gazette's analysis, show that 19 children in Arkansas died by suicide that year, a rate of 2.7 per 100,000.

The CDC collects its mortality data from state vital statistics offices, which use official death records. Those records are not public in Arkansas, as they are in some other states.

The Democrat-Gazette relied on coroners' death reports, which are public record, as well as archived news articles, Arkansas Department of Human Services records and police reports to compile its database on the causes of child deaths from 2012 to 2017.

Some coroners contacted by the newspaper said they didn't have records for every year requested because their predecessors had taken records home with them when they left office. And not all county coroners keep uniform records.

Regardless, increased suicides among young people have spurred stronger prevention efforts throughout the state, including educating Arkansans and working to remove stigmas surrounding mental health.

"One suicide is too many suicides," said Mary Meacham, the chair of education and prevention for the Arkansas chapter of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

NO ONE CAUSE

Kelsey was 9 when her mother, Ladeana Bell, first noticed mental health problems in her daughter. Ladeana drove to Kelsey's elementary school and saw the other children running and playing. Kelsey, though, was lying on the ground, lethargic and trying to take a nap.

"This little girl is really sad," Ladeana thought to herself.

Ladeana, a licensed therapist with a private practice, knew how to get help for her daughter. She'd bring up the idea of therapy, but at first Kelsey was resistant.

"Sometimes I wonder if I should have pushed harder," Ladeana said in a February interview.

Kelsey started therapy when she was 11. She said it made it difficult to foster relationships with her peers; she didn't want to tell anyone that she was going to therapy.

There wasn't one particular reason that she attempted suicide two years after starting therapy, she said. She'd gotten into a fight with a friend that day, but her problems went well beyond that.

Her eating disorder wasn't getting better, and she said she wasn't engaging with her therapy. Her depression, she said, manifested itself as anger much of the time.

"It was just things piling up," Kelsey said. "I just knew I didn't want to be alive anymore."

Experts and others interviewed by the newspaper agreed that it's nearly impossible to learn the reason for the increase in suicides by children.

"Each case is its own," Meacham said.

But, Meacham added, more research is needed, particularly into suicides by minors.

"The funding for research hasn't been there," she said. "We need to treat this like any public health issue."

One of the largest spikes in suicides and suicide attempts by children is in 14-year-olds, said Buster Lackey, executive director of the Arkansas chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Suicide is the second-leading cause of death in teenagers, according to the CDC.

Like other experts interviewed by the newspaper, Lackey cited the growing role of social media in kids' lives as one of the possible contributors to increases in suicide rates. He specifically addressed the ways in which the internet has allowed kids to bully one another 24/7 or for adults to bully children online.

"When I got on the bus or got home, it was over," he said. "It's not like that anymore."

Kelsey said social media is still hard for her -- the barrage of filtered photos depicting the best parts of everyone else's lives can make her feel like she is inferior.

Several experts also cited well-publicized cases of suicide's relation to modern technology, such as that of Michelle Carter, a Massachusetts woman who through text message encouraged her boyfriend, Conrad Roy, to kill himself in 2014. Carter was later found guilty of involuntary manslaughter.

Ladeana added that kids have access to more information, some of which may be harmful. Kelsey used to look at "dark stuff" online that encouraged self-harm, Ladeana said.

In addition to social media, Ladeana said she thinks that the country's growing political division has damaged the sense of community and decency. She formerly served as the Foundation for Suicide Prevention Arkansas chapter's research chairwoman.

"It's cattiness," she said. "There's a lot of 'mean-girl' behavior."

INVESTIGATOR AWARENESS

Another reason for the increase in reported youth suicides could be as simple as better training for county coroners, who play a key role in helping health officials understand the prevalence of types of death. More training means coroners are better able to decipher whether a death was a suicide, experts said.

Coroners determine the means of death -- homicide, suicide, accidental or natural. In Arkansas, coroners are elected by countywide vote, with the exception of Faulkner and Pulaski counties, where coroners are appointed.

There are no training requirements for coroners in Arkansas, but Lackey, a former deputy coroner in Lonoke County, said that in recent years there have been more efforts to train coroners who volunteer to learn more about investigating suicides, overdoses and infant deaths.

"A coroner has a pretty powerful position," said Lackey, who helped develop training for Arkansas coroners on investigating infant deaths.

In small towns where the coroners know the family members of the people they're visiting, it can be difficult to tell them their loved one died by suicide, Lackey said.

Still, coroners have become more cognizant of the need to classify suicides as such, Lackey said.

For example, suicides by hospice patients weren't examined closely before the voluntary training for coroners became more widespread. Some that likely should have been ruled suicides had been ruled accidental or natural, he said.

Others are seeing results from the coroner training.

"Suicides are no longer being called 'unintentional hanging' or 'unintentional drug overdose,'" said Mullins, the injury prevention specialist at Arkansas Children's Hospital.

"They're now actually being called 'suicides,' which I think is a good thing because we can't prevent something if we don't know it's happening."

Ladeana Bell said that while she thinks the social stigmas surrounding suicide and mental illness are becoming less inhibiting, they still exist and may have a bearing on decisions investigators make when noting the manner of death.

"It's very easy for someone to code it [suicide] differently," she said. "There's still a shame to it, especially in the South, especially in the Bible Belt. I think we're talking about it more, but that stigma is still there."

'REDUCE THE SUICIDES'

Reducing stigma is one of a few goals for Arkansas Students United for Mental Health, a cohort of high schoolers from Cabot High School. They aren't members of an official school club, and they are extending their member base outside their school district.

The group sprung up from an advanced placement government class assignment and grew from there, said then-Cabot senior Jayson Crumpler, a founding member and the group's head.

The group plans to implement "localized educational programs" to teach other students about mental health and the available resources. Members also are advocating for legislation that would lower the age of consent for treatment for mental health issues from 18 to 16 and set aside funding for an on-campus therapist at every high school in the state.

"I think we've succeeded in at least bringing the conversation to the table," Crumpler said.

Crumpler is working with Lackey and others at the Arkansas chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness on his project. The alliance is also pushing out fresh efforts to decrease suicides and inform the public on mental illness.

The chapter launched a HelpLine -- independent of the suicide prevention hotline -- that Arkansans can call with questions about support groups, how to access mental health care and information about mental illness. The HelpLine number is (800) 844-0381.

Three alliance members attended a two-day suicide prevention training in Fort Smith called Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training. Arkansas Children's Hospital works with members of the Arkansas chapter of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention to provide training.

The training covers how to spot warning signs of suicidal behavior -- such as changes in behavior, loss of interest in activities or social interactions, and discussion about killing themselves. It also covers debunked myths about suicide -- that asking about suicide can "plant the idea" in someone's mind, that the attempt was "attention-seeking" and should be ignored, or that suicide can't be prevented, for example.

"It's a cry for attention," Meacham said. "We better give it to them."

Training ranges from a couple of hours to two days. Some is open to the public, while some is customized to certain groups such as faith-based leaders or students, Meacham said.

The foundation will soon offer training for the workplace environment that can be accomplished over a lunch hour and training tailored toward caretakers.

The Arkansas Department of Health, which operates the in-state suicide prevention hotline, also runs suicide prevention training, said Mandy Thomas, the department's section chief for injury violence and prevention.

In recent years, the different groups have found more ways to work together, she said.

"We all want the same outcome, which is to reduce the suicides," Thomas said.

Although Ladeana was involved with the foundation before her daughter's attempt, she's gotten more involved since then.

As Kelsey has progressed in her recovery, she, too, has gotten progressively more involved.

Her recovery also was something she had to consider before choosing to major in a mental health field.

"It was kind of a healing opportunity for me," Kelsey said.

Anyone experiencing suicidal thoughts can call the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at (800) 273-8255 or the Arkansas Crisis Hotline at (888) 274-7472.

HOW WE DID IT

To produce this and other articles in this series, Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reporter Ginny Monk reviewed thousands of pages of documents, photographs and videos obtained from county coroners, local police departments, news archives and state prosecutors.

Information gleaned from these sources enabled Monk to build a database with details about more than 1,500 deaths of minors from 2012 to 2017. Data from 2018 and 2019 was unavailable at the time this series was produced.

Monk submitted public records requests to every prosecutor and county coroner in the state. Some prosecutors said they no longer had files for some cases. A few coroners provided only redacted records and some did not provide all the records for the time period requested, saying their predecessors had taken records home with them.

The database includes demographic information, contacts the children had with Arkansas Department of Human Services workers before their deaths, details about the circumstances of their deaths and any criminal charges filed in their deaths. It includes all causes of deaths but does not include miscarriages or stillborn babies unless charges were filed in those cases — a rare occurrence.

Monk analyzed this data to determine which cases were ruled the result of abuse or neglect or whether the children were in foster care at the time of their deaths.

She then conducted interviews with current and former investigators, family members, health specialists and experts in child abuse and neglect.

Support for Monk’s reporting on this project also came from her participation in the 2019 Data Fellowship, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism at the University of Southern California.

CREDITS

Reporting: Ginny Monk

Editing: Sonny Albarado

Copy Editing: Chris Carmody

Graphics/Illustrations: Carrie Hill, Aaron O’Quin

Photos: Ben Goff, Yutao Chen

Web Design: Yutao Chen

Page Design: Terry Austin

Dustin Moore (from left), Paige Thielbar and Tina Polk of Bentonville display their Team Semicolon tattoos in September 2016 during an annual walk to memorialize those lost to suicide and to raise awareness of suicide prevention. The team name and tattoos are inspired by Project Semicolon, a nonprofit campaign to bring hope to people dealing with depression, self-harm and thoughts of suicide. (NWA Democrat-Gazette/Ben Goff)

Nation sees spike in suicides by minors

Minors and suicide in Arkansas

Warning signs of suicide

[This article was originally published by Arkansas Democrat Gazette.]