As COVID-19 Devastates Their Community, Can 17 Second Graders And Their Teacher Make Up What The Pandemic Took Away?

This project by Sarah Karp was reported with the support of the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 National Fellowship.

Her other stories include:

A Most Unusual School Year: Part I

Death, Job Loss And Remote Learning: The Pandemic’s Toll On One Chicago Family

Michelle Kanaar / WBEZ

The names of some children in this story have been changed to protect their privacy.

Olga Contreras stands alone in an empty classroom at Saucedo Scholastic Academy. The public school is in a sprawling old building in Chicago’s Little Village neighborhood. It usually has almost 1,000 students filling its hallways. But on this grey first week of school, there is an echoey quiet.

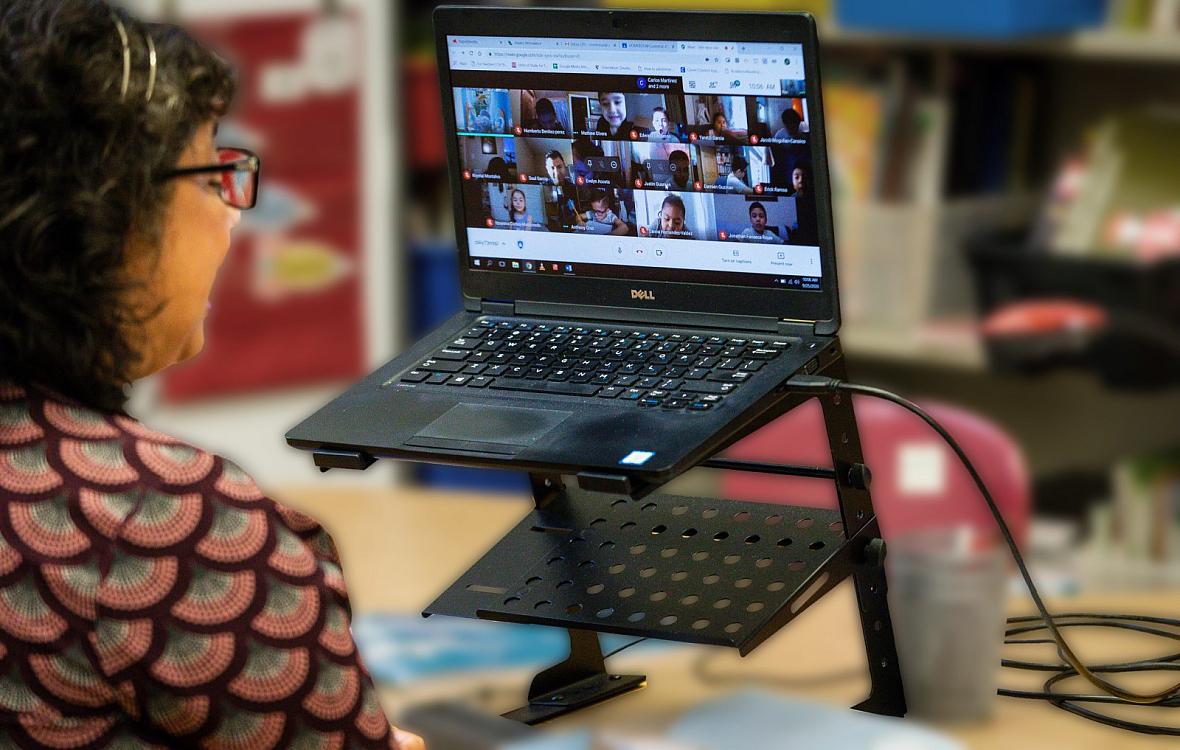

Contreras puts her coffee to the side and props her laptop atop a children’s table just two feet high. She then lowers a chair as far as it can go and sits down to wait as the children come popping into the Google Classroom. Their little voices, “Hola Maestra. Hola Maestra,” fill the room like music.

Contreras brightens up. She is delighted to see all 17 of her second graders. She is especially happy to see Maria with her chubby cheeks, and James whose eyes sparkle in the dark room. She had worried they would not show up.

She also takes note of Mark. She knows he has attention issues. And of a little girl who is so shy she is terrified to be on the screen. She keeps clicking off her camera.

The other children seem happy to be there and to see Contreras — their teacher with curly brown hair whose ready smile shows her dimples.

Before this first week, Contreras was so worried about remote learning during the pandemic that she had considered a leave of absence. But once she decided to do it, she threw herself in.

“Everything is going to be good,” Contreras said that first week in September, as if to reassure herself. “I don’t know how or why. Good or bad, we are going to make it good.”

During the first quarter this fall, Contreras had many happy surprises. Her attendance was strong. And even at a distance, she saw the children get more comfortable, light up and learn. Just as when they are in class with her, she finds joy in them.

But she also confronted the academic damage caused by the pandemic. After the virus abruptly shut down in-person school in March, followed by a chaotic spring, it had been five months since these children had been in an organized class.

In that time, the pandemic upended Little Village, just like it had other poor Latino and Black communities in Chicago and across the country. The Southwest Side community faced more sickness, more death, more unemployment than other places. And the need for a safety net was greater than ever, but it was almost non-existent for this community of mostly Latino immigrants. These hardships were inescapable as students learned from home.

“The consequences here are not theoretical. Research tells us that if we do not act with urgency we will be in danger of losing a whole generation of students.” — LATANYA MCDADE, CHIEF EDUCATION OFFICER FOR CHICAGO PUBLIC SCHOOLS

For Contreras’ second graders, it was a critical moment. By third grade, if children can’t do math or read well, they are more likely to drop out of high school, live in poverty and go to prison. And Contreras’ students are also Spanish speakers. They have the added pressure of learning English.

School district leaders highlighted the dire situation.

“Our students are hurting right now, especially our most vulnerable students,” said Chief Education Officer Latanya McDade at the November Board of Education meeting, pointing to data showing more students earning failing grades than normally. “The consequences here are not theoretical. Research tells us that if we do not act with urgency we will be in danger of losing a whole generation of students.”

But Contreras’ students also had a lot going for them. Their school is highly rated with a principal who taps every resource to support staff and get students what they need. Most have committed parents who desperately want a good education for their children.

And they have Contreras. She is an experienced and determined teacher. She’s also an immigrant herself. She is at once strict and a well of empathy. Still, she’s haunted: Will it be enough? Will her students make it?

En septiembre, Olga Contreras comenzó a enseñar a sus estudiantes de forma remota desde su salón de clases en Saucedo Scholastic Academy. Ella no tiene un escritorio de maestra porque normalmente camina todo el día. Este otoño, se sentó en una mesa para niños. (Michelle Kanaar / WBEZ)

“I was one of them”

Contreras got a sense of how difficult this year was going to be even before school started. At a late August open house on the wide grassy lawn in front of Saucedo, Contreras told the parents she needed them. She wanted them to help their children log in for remote learning and keep track of time. She also gave them a package of workbooks.

At the end, Maria’s mother told Contreras that she and her husband had to work and there was no one to help with remote schooling. Contreras suggested the child care offered by the school district. But the mother said she had two family members die of COVID-19. She was scared to drop off Maria anywhere.

Contreras pushed the mother: “What do we want for her? Do we want her just to be sitting in front of TV?” Contreras could feel the woman’s anger, not so much at her, but at her life being profoundly disrupted, she said.

The mother of James, the boy whose eyes light up in the dark, did not come to pick up the workbooks. She said she was too busy. As she did with Maria’s mother, Contreras guilted her. Contreras is in her early 50s — old enough to be the parents’ mothers.

“You cannot ask him to be in class because he’s going to feel embarrassed,” Contreras told her. “That’s just awful for the kids.” Finally, the mother came to get the materials. Contreras told her how beautiful she was and thanked her. The woman’s sour attitude sweetened a bit.

Contreras thinks the mother might be lonely and overwhelmed. She’s far from her native Ecuador and isolated in her apartment with at least three children. She told Contreras that her husband works long hours, six days a week.

“I know what the parents go through,” Contreras said one day after class. “I was one of them.”

When Contreras first came to the United States from Mexico, she and her husband picked strawberries and then worked in Chicago factories. Contreras said she and her husband eventually divorced after a troubled marriage. She remembers being so homesick.

Contreras found respite volunteering at her son’s preschool. “I could not speak English and I felt so embraced and it was just very contagious,” she said. Contreras was eventually hired as a teacher’s assistant and then, seven years later, she became a teacher. She also pushed her three sons. They came through Chicago Public Schools and all became engineers.

Contreras is considered a master teacher, not just for how she works with children, but also with parents. Yet, opening the computer this September, Contreras felt like a novice.

The direction from Chicago Public Schools was not to make up for losses during the shutdown. Instead, teachers were told to dive into grade level material. Accelerate learning, don’t backtrack.

Contreras was on board with this, but she was not confident about remote teaching. She had training in how to use the Google suite. Eventually, the school district also provided better equipment, including a laptop stand and a document projector. But it did not provide what she needed most: training on ways to get students engaged and excited about learning online.

She didn’t know the emotional or academic state of her students. She didn’t know if they would even show up. She had no idea what to expect.

Contreras habla con los padres y estudiantes fuera de la escuela una tarde de noviembre. Ella insta a los padres a que tomen un papel activo para ayudar a sus hijos durante el aprendizaje remoto. (Michelle Kanaar / WBEZ)

Making connections

In the first week, her mostly 7-year-old students were still figuring out how to mute and unmute. For several days, one child had his microphone on during his mother’s intense morning prayer group. As Hail Mary boomed in Spanish, Contreras couldn’t help but laugh. “The children looked so confused,” she said.

Contreras spent much of the week reading Stand Tall Molly Lou Melon. The book is about a short brown girl who gets bullied by a boy at school. It was a jumping off point to talk about resilience and to ask students about times they were sad.

“I was sad I could not go on the slides this summer,” one boy said in Spanish. The children mostly speak to her in Spanish and, especially early in the school year Contreras teaches in mostly Spanish.

“Yes,” Contreras said, knowing the playgrounds are closed due to the pandemic. “You have to become a scientist and make your own slide.”

Another boy in a small plaintive voice said he felt bad when his cousin died. His grandmother rubbed his back.

“I am glad you are telling us this,” Contreras told him. “Maybe you can write him a letter and tell him how much you miss him.”

Contreras made a note to see if the family would like the little boy to talk to someone. Saucedo has a 10-person social emotional team that includes the counselor, a social worker and several staff from outside organizations brought in by the principal.

Especially early on, Contreras lavished the children with compliments every time they spoke up. Students can’t learn if they don’t feel safe, she said. Good job, she said often. “Buen trabajo, Jonathan. Buen trabajo, Yaretzi.”

But after class, Contreras shared her worries about the students’ one word or short sentence answers to questions. “They were just more hooked into the emotion of the moment, but they were not able to express it,” she explained.

Contreras said she suspects they’ve been watching too much TV and having few discussions with their parents while they’re home during the pandemic. Contreras attributed this in part to the separation in her Latino culture between adults and children. Respecting elders is paramount.

“In our culture it is only commands,” Contreras said. “Bring the salt. Do your homework. Take care of your baby brother. There is not a lot of ‘tell me about this.’” Contreras stressed she’s not judging the parents. It is about understanding their backgrounds.

As a teacher, she knows conversation skills — putting thoughts and arguments into words — are critical. They are the foundation of learning to read and write.

Still, Contreras sees an opportunity. Many of the parents are home, many sitting right behind their children during class. They have no choice but to be involved, she said.

She devised a plan for breaking through. She’ll create fun projects that parents can do with their children, projects that will get them talking.

Para ayudar a crear un sentido de comunidad, Contreras hizo un collage de fotos de sus estudiantes y sus padres. Después de configurar su salón de clases, ella les dio un recorrido virtual. (Michelle Kanaar / WBEZ)

Little virtual hugs

For her first assignment, she asked her students to create a poster celebrating family and culture — and it was a hit. From their computers at home, the students eagerly presented what they made with their parents.

One boy showed his aunt in Mexico, a mariachi musician, and his two favorite teams: the Guadalajara futbol club and the Blackhawks hockey team. His mother was next to him, telling him what to say next. After his presentation, students could ask him questions, but mostly they just complimented him. “I love your flag,” a boy said. “Gracias,” he answered, with a proud smile.

Contreras loved these moments of kindness. They were like little virtual hugs.

Nearly every day, at least one moment impressed her. Even the students she worried about most had breakthrough moments. One day, James’ mother surprised Contreras and left a voicemail message of the little boy counting. Before that, the little boy in a dark corner had never spoken up in class. Contreras did not know he could count.

If science were in person, Contreras’ students would have spent most of the first quarter in the school’s garden, learning about habitats. As it was, she sent the children outside to observe. Mark, the little boy who can’t sit still in class, was calmed by the trees and the grass. His mother sent Contreras a picture of him sitting on a folding chair in the shade drawing.

When Contreras planted two seeds and put one on the windowsill and one in the closet, one girl announced she knew the experiment’s results already. “The seeds need the sun to grow,” she said.

And Contreras took steps to make remote school look more like regular school.

A few weeks in, she transformed her room. She printed out photos she took of the children at the open house and put one on each desk. She decorated the bulletin boards. Then, she gave the students a virtual tour of the room. The children were thrilled as they pointed to their favorite decorations. She told them the classroom was waiting for them.

En una jornada de orientación, Contreras imprimió las fotos que tomó de los estudiantes y puso una en cada escritorio. (Michelle Kanaar / WBEZ)

A shaky foundation

Early on in the quarter, she quizzed the students to see if they could read 90 words. That’s what’s expected at the start of second grade. The first student’s result was a mere 23 words. Among 10 others, just one was above 90. The last six students had nothing next to their names. They could not read even one word.

Some education experts maintain that the risks aren’t especially great for students with deficits this fall. If a student’s foundation is strong, they should be able to regain skills pretty easily, said Rebeca Itzkowich, a senior instructor at Erikson Institute, a Chicago organization that studies and offers training in early children education. She said if they got solid instruction until March, they should be OK. “You know, once you learn something, nobody can take it away, even if you’re not in school,” she said.

But not all students left school in March with a strong foundation. In fact, even in a normal year, half of all Chicago Public Schools second graders test below national norms. By eighth grade, about 70% meet standards, so while many catch up, a significant number don’t. Some schools are far worse. Saucedo is about average.

And regular classes weren’t the only thing disrupted. Take Mark. During class, he sometimes stands on his chair or runs around it. One time, he even did a handstand in front of the screen. One day, his mother came to the school distressed. “He can answer your questions, but is not paying attention,” she told Contreras. Contreras nodded her head and suggested getting the little boy a stress ball.

But Contreras knows he needs more. She has two students with diagnosed learning disabilities and others who get help with speech. These students didn’t get any extra support in the spring nor in the summer, as many students in special education usually do. This fall, clinicians and a special education teacher worked with the students separately online. But like the stress ball, it is not enough.

Desde mayo, el estacionamiento de la escuela Saucedo se ha transformado en un sitio de pruebas gratuitas de la ciudad. Este otoño, la fila de autos que esperaban por pruebas a menudo se extendía por cuadras. (Michelle Kanaar / WBEZ)

Contreras is also concerned because students aren’t doing work on their own. They show up in class, but many aren’t doing the two hours of reading and math expected of them each day without their teacher. That means rather than the six hours of instruction they would be getting in normal times, they are getting just three.

This comes as the odds of returning to in-person school drop with each passing day.

As the fall wore on, the number of COVID-19 cases kept climbing. Once again, Little Village became a hot spot. Outside Saucedo, the school’s parking lot is a testing site. The lines had slowed to a trickle in August, but by mid-fall the cars waiting for tests stretched for blocks.ith each passing day.

Parents alongside students

All fall, Contreras was constantly coming up with new ideas for projects her students could do at home with their parents. For math, maybe recipes. For the science unit on materials, maybe make pinatas. But she hesitated.

“To be mindful that the parents are having these financial issues,” she said. “You know that really breaks my heart. I don’t want to ask for more.” Teachers in Chicago were only given their regular stipend of $250 this year.

Contreras noticed that fathers were present at home alongside the moms. To her, it was a sign that perhaps no one in the home had a job. Contreras was particularly disturbed by this. She imagined stress building around her students.

While Contreras needed parents there, their presence was also a source of tension. One day Contreras asked a little girl to stay after class and read to her. When the super shy girl hesitated, her mom was seen on the Google Classroom hitting her. Contreras suspects the mother is upset because the little girl is struggling so much. Contreras met with the mother and begged her to leave the girl be.

“I want to make a change in his life, I want him to see that he can make it. But he needs a lot of affection and I can only give that to him in person.”— OLGA CONTRERAS

Then, there are the children whose parents aren’t as attentive. Maria, the little girl whose mother threatened to keep her out of school, often seems on her own while at her parents’ workplace. Contreras thinks the girl knows how to play games on her computer and isn’t paying attention. Perhaps that girl does not think anyone cares, Contreras said.

Then, there’s James. His mother is trying, but when he unmuted his microphone, the noise was intense. There was chatter from other classrooms and his little sister was running around. Contreras loaned him a desk from Saucedo to give a place to work.

If he was in her class in front of her, Contreras said she would give him a lot of one-on-one attention. She would wrap her arms around him. “I want to make a change in his life, I want him to see that he can make it. But he needs a lot of affection and I can only give that to him in person,” she said.

Contreras se acostumbró a enseñar de manera remota a medida que avanzaba el otoño. Ella obtuvo una cámara para documentos que le permite mostrar el trabajo de sus alumnos en tiempo real. (Michelle Kanaar / WBEZ)

A widening academic divide

Last spring, researchers and other experts sounded alarms about expected huge pandemic-related learning loss. Several studies using tests taken this fall are showing the real-life impact. One, by the global management consulting firm McKinsey & Co., found that students on average lost one and a half months in reading and three months in math. Importantly, it found that Black and Latino students had much more significant losses.

Chicago Public Schools canceled all standardized tests this fall, but school districts that have tested students are seeing this play out. In Dallas, the superintendent there called the results of a standardized test given this fall “horrifying.” Half the students lost ground in math and a third in reading, with Black and Latino students doing far worse than white students. There were similar results from an early literacy test given to students in Washington, D.C — students just like the ones in Contreras’ class.

If not addressed, these losses will compound, said Bryan Hancock, a partner at McKinsey. The fear is that students from middle- and upper-middle class families will emerge unscathed from the pandemic, and the already sizable gap between their performance and that of poor students will widen.

Some Chicago Public Schools teachers say they are seeing this disparity. One teaches at a diverse school in the upper middle class neighborhood of Hyde Park. In the spring and summer, these children spent time with books and talking with parents. This fall, their parents are with them, teaching alongside the teacher.

“It’s almost like homeschooling with a lot of guidance and direction,” said Gabriel Sheridan, who has a split first and second grade class at Ray Elementary School. “For those kids it can be very successful because they’ve got somebody there to help them pull it together.” But she also sees the divide. She has one child without much support and he is faltering.

So what happens if students emerge from the pandemic even farther apart than they already were?

Contreras has an opinion on this. She doesn’t believe her students — children of poor immigrant families — will be given much leeway. That is what drives her. That is what keeps her up at night.

La directora de la escuela Saucedo colocó estos letreros por todo el plantel. Ella dice que aunque los estudiantes no están ahí, ella quiere que las familias sepan que ellos todavía son parte de la comunidad. (Michelle Kanaar / WBEZ)

Measuring the pandemic’s impact

Throughout the fall, Contreras felt like she was flying blind. She needed to know exactly where her students were struggling. She decided to give them a standardized test, even though neither Chicago Public Schools nor her principal were demanding it.

“It’s going to show how my teaching … good or bad, if I am producing or not,” Contreras said in the sixth week of the nine-week quarter. ”So let’s say [James] is on level A. He can’t read. If it’s the middle of the year and he is on Level A. Man …”

The results were even worse than she feared.

Near the end of the first quarter in late October, she called a parents meeting. A very important meeting, she told them.

This is what she told them: There wasn’t a single student in the class reading at or above grade level.

“Zero. Zero,” Contreras told. In Spanish, she said usually at least half her students read at or above grade level. “This time, it was zero.”

But she pivoted immediately to offer hope. It’s not your fault, she told them. It is the fault of the pandemic. But she desperately needed their help.They have to encourage their children to read and write — and they have to do it with them.

And with a deep breath, she ended with this: “I am very excited, parents, because this is a very historic moment for everyone. As parents, as children, as teachers, we can beat the pandemic.”

She then asked if there were any questions. There were none.

Regrouping and moving forward

Contreras thinks the parents didn’t question her because they trust her. She’s the teacher. She’ll know how to fix it.

And Contreras did have a game plan.

She would split the students into four small groups, with a different adult leading each one: herself, the student teacher, the special education teacher and a teacher’s assistant. The students would get a lot of individual attention.

But her ambitious plan suffered a blow before it could get underway.

The special education teacher transferred to another school. Not only could the class no longer be split into four parts, her substitute special education teacher was not bilingual.

Contreras was angry at first. Good special education teachers are in short supply, especially those who speak Spanish. In fact, Chicago Public Schools is still looking to fill 260 open positions as of Dec. 1. That is about 6% of the 4,600 special education teacher positions in the district.

But quickly, Contreras devised a new plan. She took half of the class; while her student teacher and the teacher’s assistant each split the remaining eight lowest-performing students. It was not ideal, but Contreras had to move forward.

Un mural en el campus de la escuela Saucedo dice: “sí se puede” en español. Alrededor de 40% de los estudiantes están aprendiendo inglés. (Michelle Kanaar / WBEZ)

Bridging the divide

As the quarter drew to a close in early November, Contreras remained determined. Every day she has a lot of wins. Shy children speaking up. Impromptu conversations. Children willing to be silly. It lets her know they feel safe.

James sits at the desk she got for him. He even put a picture on the wall behind it that says “Saucedo.” Mark plays with a toy during class to help keep him focused. Maria’s parents met with Contreras. She’s trying to get them to see that Maria needs more attention.

The principal has 400 new headphones for students and is interviewing for the special education position. Contreras trusts the principal will find someone good.

Yet Contreras cannot hide her worry. The pandemic is getting worse. The testing site right outside the school has never been so busy. More mothers and fathers tell her they are being tested or their family members are sick or have even died. Businesses are again shutting, leading to even more job loss.

She knows her students feel all of this.

The school district announced that elementary school students would come back for in-person learning on Feb. 1. Like most teachers, Contreras would like nothing more than to see her students, but she’s skeptical about it happening anytime soon.

Contreras terminó el trimestre de otoño sabiendo cuán atrasados están sus estudiantes, pero también sintiéndose esperanzada de lo qué podrían lograr este año escolar. (Michelle Kanaar / WBEZ)

Contreras is trying her best, but she fears it isn’t enough, especially for students like James and Maria. What they really need is someone to put their arms around them and tell them they can make it, she said.

Right now, the distance between them feels too great.

Sarah Karp covers education for WBEZ. Follow her on Twitter @WBEZeducation and @sskedreporter. The story was edited by Kate Grossman and Cate Cahan. Production design and graphics are by Katherine Nagasawa. The audio story was scored and mixed by Justin Bull. Photos by Michelle Kanaar.

This story was reported with the support of the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 National Fellowship.

[This story was originally published by WBEZ.]