Dealing with dementia: Tim Fitzmaurice shares his story

Award-winning reporter covering Santa Cruz business, housing, healthcare and Santa Cruz County government. Reach the author at jgumz@santacruzsentinel.com or follow Jondi on Twitter: @jondigumz.

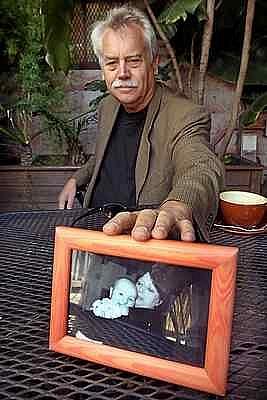

Former Santa Cruz mayor and former councilman Tim Fitzmaurice reaches for a picture of his wife Ginny holding their granddaughter. Ginny died in 2014 from a type of dementia that took away her thinking abilities. (Dan Coyro -- Santa Cruz Sentinel)

SANTA CRUZ — When Tim Fitzmaurice lost his wife Ginny, his partner of 44 years, to dementia in 2014, his experience as her caregiver brought him so much pain and guilt that he kept it to himself.

Until Tuesday.

He spoke to the Santa Cruz County Board of Supervisors on behalf of the Alzheimer’s Association, asking county health staff to reach out to families dealing with dementia, a disease with no cure that affects 590,000 Californians including 4,000 locally.

Over six years, he and Ginny saw dozens of doctors, locally and in San Francisco, as she was treated for melanoma but no one asked why he answered every question and why she grew more confused.

WARNING SIGNS for DOCTORS

The California Department of Public Health posted a “Provider Guide to Understanding Dementia” on its website in March 2016.

Any of these warning signs may warrant assessment for dementia:

• Patient is confused about appointment date, location or medications.

• Missed appointments.

• Patient cannot remember recent conversations.

• Patient defers to caregiver to answer questions.

• Patient has difficulty providing medical history.

• Patient is dressed inappropriately or has poor hygiene.

• New onset of social withdrawal or depression.

• Increased emergency room visits, frequent falls, weight loss.

The state Health Department provided the guide to the directors and staff of the 10 California Centers for Alzheimer’s Disease including those at UC San Francisco and Stanford University. Between 2014 and 2015, those centers educated 16,738 health care professionals and social service providers on dementia, according to an agency estimate.

California has 49,000 primary care physicians and 53,000 specialist physicians.

Fitzmaurice, 67, a writing instructor at UC Santa Cruz who was twice elected to the Santa Cruz City Council and served a year as mayor, spent eight years caring for Ginny.

“We needed to be taught how to live with this catastrophe. We weren’t,” he wrote in April to Sen. Bill Monning, D-Carmel, asking him to champion a $2.5 million allocation in the $171 billion state budget to provide low-cost diagnostic tools for dementia to primary care doctors.

The goal is to reduce unnecessary referrals to high-cost specialists and expensive imaging tests.

That item is in the budget the Legislature passed last week, putting it in Gov. Brown’s hands.

“We are keeping our fingers crossed,” said Ruth Gay, chief public policy officer for the Alzheimer’s Association Northern California and Northern Nevada.

WHY SILENCE?

Fitzmaurice sat down with the Sentinel to share his story.

He stayed silent, he said, because Ginny did not want him to tell friends or family members.

“She told me she’d divorce me,” he said.

She was 56 when he noticed something. She would start to say something, then stop, unable to finish her thought, and say “Oh, never mind.”

But he didn’t know what the problem was.

A turning point came when she needed help with a project at UCSC where she was a residential life coordinator.

“I don’t think she’d ever asked me for help,” he said.

He recalls laying out the materials on a conference room table in City Hall — it was 2005 and he had one more year in office — and she couldn’t alphabetize.

“Then I knew,” he said.

When she was unable to organize the alumni party, he did it for her.

She retired that year.

The next year, when she got the cancer diagnosis, she focused on that.

“It was something she could struggle against and win,” Fitzmaurice said.

TAKING CARE

Finally after six years of seeing doctors, a gynecologist admonished him for answering all the questions posed to Ginny.

What led him to find support groups was Ginny’s jury duty notice. In getting a neurologist’s note to excuse her, he got a referral to the Alzheimer’s Association.

The two would walk downtown every day, taking the same route, because he wanted her to remember the path in case she wandered away.

As Ginny’s cognitive skills declined, she could be combative, not wanting to get into the car for a drive, prompting passersby who didn’t understand to scold her husband.

“I chose to be a caregiver,” said Fitzmaurice. “I failed every day. I always fell short of what I thought I should be doing.”

In 2012, a Stanford neurologist talked to him and Ginny for hours, reviewed CAT scans, and came to the conclusion she had frontotemporal disorder, a form of dementia that affects people under 65, taking away thinking and communicating and upsetting the emotions.

Fitzmaurice put his hand on his forehead, recalling how the neurologist said she had one to five years to live.

At the Alzheimer’s support groups, he felt out of place, a man among female caregivers and a generation younger than those caring for their parents; symptoms of Alzheimer’s typically appear at age 70, according to state data.

One participant told him, “You should place her,” using a euphemism for institutionalization.

He couldn’t do that.

He found a caregiver to help him six hours a week.

SEEKING JUSTICE

Toward the end, doctors recommended psychotropic drugs, which can reduce anxiety but can be life-threatening.

Fitzmaurice said no at first, then changed his mind, relieved the drugs had a calming effect on Ginny so she could stay at home.

He had help from Hospice of Santa Cruz County for the last six weeks.

“They’re great, caring people,” he said, recalling when he asked for a hospital bed, it arrived in three hours.

At Ginny’s memorial, 250 people attended, many women who learned from her guidance and became leaders.

“She was a fighter for justice,” said Fitzmaurice.

Though he had retired from UCSC in 2011, he returned to teaching.

He has a 20-year-old grandson and a 12-year-old granddaughter in Southern California.

Through his new partner, Laurie Brooks, he began teaching writing once a week to inmates at Soledad, which he describes as “reinvigorating.”

He wants to make a difference for 590,000 California families living with Alzheimer’s.

“The devastation it causes to families is unbelievable,” he said. “It doesn’t go away.”

CAREGIVER RESOURCES

Living With Alzheimer’s for Caregivers, Middle Stage: Series June 30, July 7 and 14: Must attend all three, 10:30 a.m to 12:30 p.m., Elena Baskin Live Oak Senior Center Annex, 1777-A Capitola Road, Santa Cruz. Facilitator: Dale Thielges. To register, call 800-272-3900. Information: Meg Kaminski, mkaminski@alz.org.

Online webinars: Topics include conversations about Alzheimer’s, connecting with a person with Alzheimer’s, responding to challenging behaviors, addressing sleep challenges, benefits of physical activity on cognitive decline. Alz.org/norcal/in_my_community_63876.asp.

24/7 Helpline: 800-272-3900.

California Department of Public Health: Health provider guides to detecting and understanding dementia, caregiver guides to nutrition for a healthy brain, Cdph.ca.gov/programs/Alzheimers.

SB 613: Signed in October by Gov. Jerry Brown, requires the state health department to update 2008 guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease management and report to Legislature by March 1, 2017.

Voluntary state income tax checkoff for Alzheimer’s research: $504,743 donated by taxpayers in 2015.Ftb.ca.gov/individuals/vcfsr/reports/003.pdf.

WARNING SIGNS FOR DOCTORS

The California Department of Public Health posted a “Provider Guide to Understanding Dementia” on its website in March 2016.

Any of these warning signs may warrant assessment for dementia:

• Patient is confused about appointment date, location or medications.

• Missed appointments.

• Patient cannot remember recent conversations.

• Patient defers to caregiver to answer questions.

• Patient has difficulty providing medical history.

• Patient is dressed inappropriately or has poor hygiene.

• New onset of social withdrawal or depression.

• Increased emergency room visits, frequent falls, weight loss.

The state Health Department provided the guide to the directors and staff of the 10 California Centers for Alzheimer’s Disease including those at UC San Francisco and Stanford University. Between 2014 and 2015, those centers educated 16,738 health care professionals and social service providers on dementia, according to an agency estimate.

California has 49,000 primary care physicians and 53,000 specialist physicians.

[This story was originally published by Santa Cruz Sentinel.]