Fentanyl became LA’s deadliest drug in 2022 and hit Black community hardest

The story was originally published by the Los Angeles Daily News with support from our 2023 Data Fellowship.

A man trades fentanyl for meth in a Los Angeles alley. Many fentanyl users also use meth to stay awake, especially at night so they don’t get ripped off on the streets.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

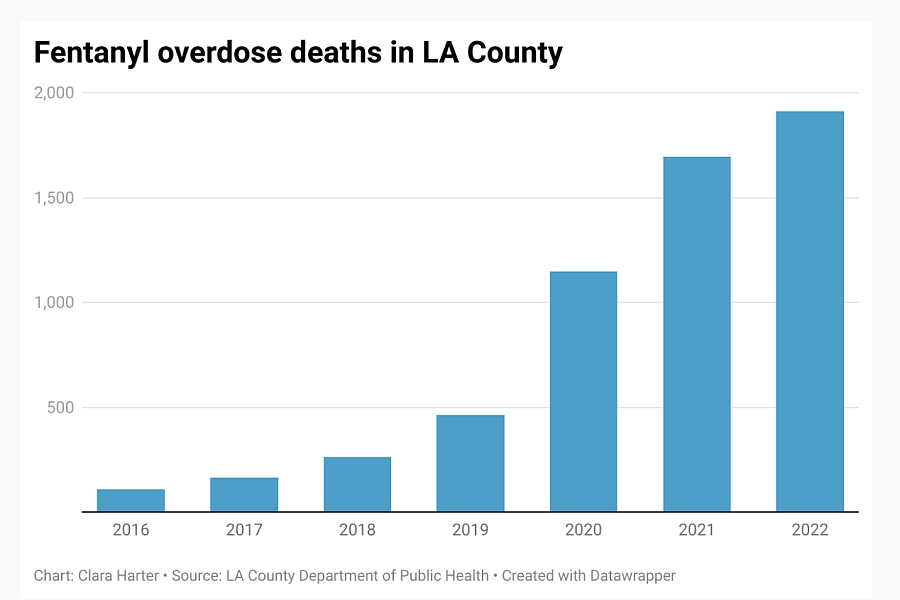

Fentanyl killed 1,910 LA County residents in 2022, overtaking methamphetamine as the leading cause of overdoses and taking Black residents’ lives at a higher rate than any other racial/ethnic group.

That’s according to data from L.A. County’s public health department, which recorded a 13% spike in fentanyl deaths in 2022 compared to the year prior — and a staggering 1,652% increase from the 109 deaths first recorded in 2016.

The synthetic opioid, which can be lethal in quantities as small as a few grains of sand, has been steadily claiming more lives every year since the county began tracking fentanyl deaths, although last year’s jump was lower than that seen in 2021.

“It does look like we’re slowing down (the rate of increase), but I don’t think any of that makes the situation better, given that we’re still in the worst overdose crisis in history,” said Dr. Gary Tsai, director of substance use prevention and control at the L.A. County Department of Public Health. “At no point in time has there been more overdoses than now.”

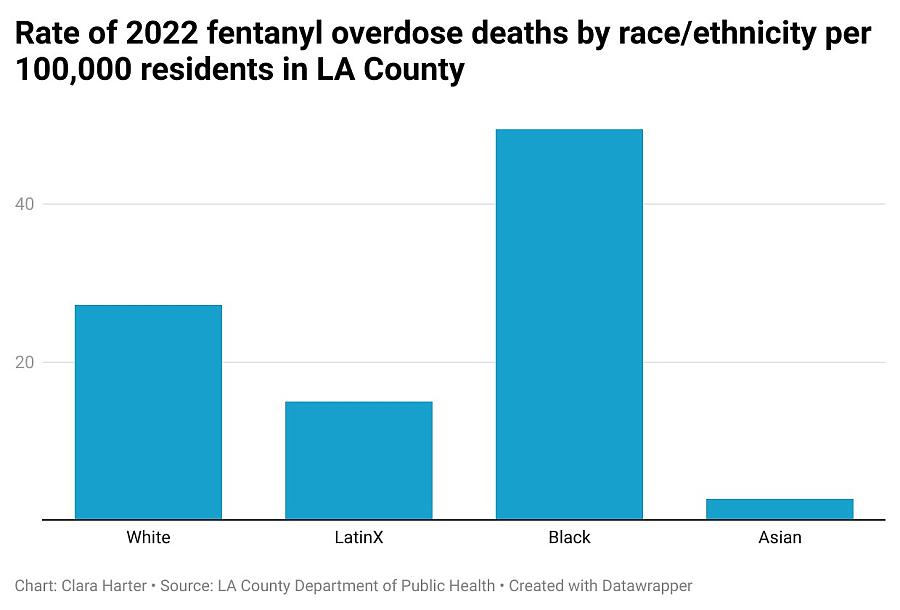

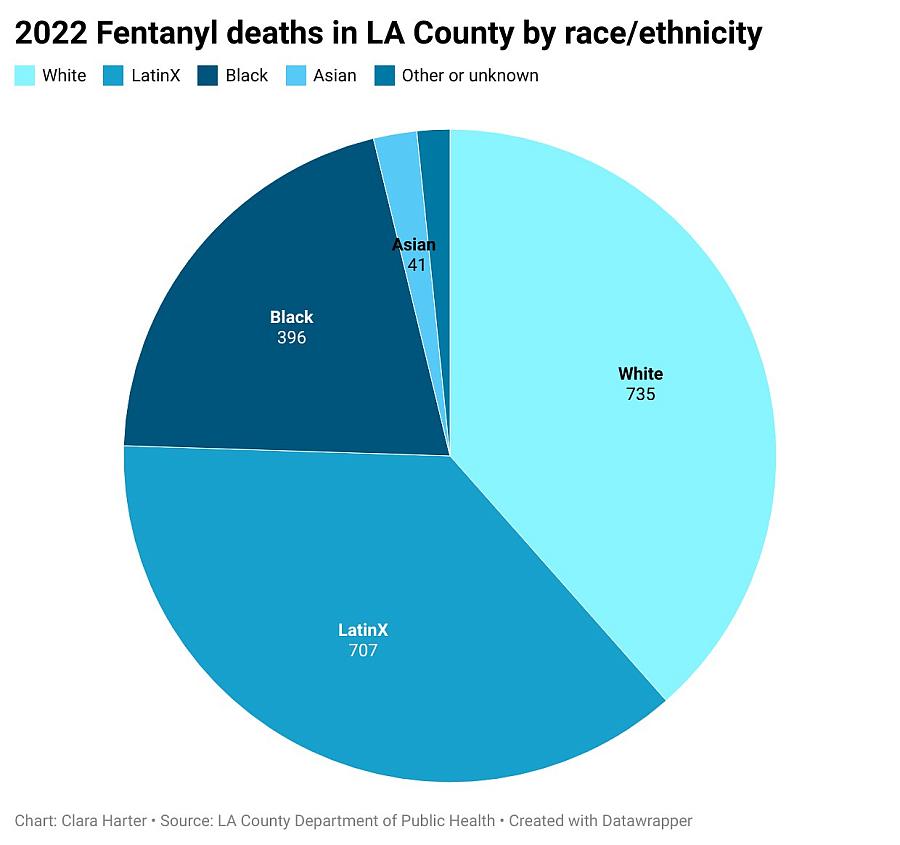

Public health officials have said they are also alarmed by the growing racial disparities seen in the fentanyl death data: While Black residents comprise 8% of the county’s population, they made up 21% of the deaths last year.

“It’s really striking what the rates are now for Black individuals dying of fentanyl,” said David Goodman-Meza, substance use researcher and assistant professor at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine.

“Unfortunately, because of systematic racism that Black individuals suffer in Los Angeles County, they tend to live in more marginalized communities,” he added. “And they are less likely to access services.”

When fentanyl first arrived in Los Angeles circa 2016, White residents were dying at the highest rates. But over the past seven years, the share of people of color dying has steadily increased.

The public health department counts a fentanyl overdose as any accidental death in which the L.A. County Medical Examiner-Coroner records fentanyl as one of the causes. In some cases, several drugs may be listed under causes of death.

In 2019, Black and White residents both died from fentanyl overdoses at a rate of 7.2 people per 100,000 residents. That death rate skyrocketed by 2022 and hit the Black community hardest, with 49.5 deaths per 100,000 residents — almost twice the rate of White fatalities, which was 27.2 per 100,000 residents.

Latino residents in L.A. County represented 37% of all fentanyl deaths in 2022. However, proportional to population size, Latino residents died at a lower rate than White and Black residents — at 15 deaths per 100,000 residents.

Experts say they don’t know why Latinos die at proportionally lower rates, but have noted that there may be cultural preferences for different substances or possibly a smaller network of fentanyl dealers in Los Angeles’ Latino community.

Still, with 707 fentanyl deaths recorded in 2022 — an all-time high — Latinos are not escaping the epidemic unscathed.

Public health experts say the rise in deaths among people of color can be attributed, in part, to the rapid evolution of fentanyl’s availability combined with the disadvantages faced by marginalized communities.

People wait to get into the Midnight Mission as Los Angeles Fire Department firefighters from the Skid Row station respond to a call on Tuesday, November 28, 2023. Fentanyl overdose numbers continue to rise in the area.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

In the early days of the epidemic, Tsai said, people who used fentanyl were often seeking an alternative to prescription opioids, a population that perhaps leaned White.

“There are studies that show White populations’ greater access to pain medication,” he said. “In the case of the early days of the fentanyl epidemic, that health disparity backfired on the White population.”

Now, fentanyl is easy to buy and can be laced into almost any street drug. That means any population at a higher risk of using illicit drugs is also at a higher risk of fentanyl overdoses, said Chelsea Shover, health services researcher and assistant professor-in-residence at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine.

“Fentanyl death rates among African Americans rising in L.A. is in line with what we see in the national stats, and in terms of all the different overlapping public health risk factors that people of color face,” she said. “People experiencing homelessness are quite overrepresented among drug overdoses generally and African Americans are absolutely overrepresented among people experiencing homelessness.”

Charles Porter, a longtime activist on Skid Row, has watched firsthand as fentanyl ravaged the neighborhood’s Black population. Porter provides substance-use resources and organizes community events for people living on Skid Row through the United Coalition East Prevention Project, an initiative of the nonprofit Social Model Recovery Systems.

Michael Calloway, left, greets Charles Porter, project coordinator for United Coalition East Prevention Project, as he runs a harm reduction evening at Gladys Park on Wednesday, November 8, 2023 in Skid Row in Los Angeles. The outreach organization is working to stem the uptick in fentanyl overdoses

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

“Many people that overdose from fentanyl don’t know that they’re using it,” Porter said. “There are a lot of people that are using either crack cocaine or methamphetamine that is tainted with fentanyl. I know there are also some recreational fentanyl users.”

In the three ZIP codes encompassing Skid Row, more than 52% of 2022 fentanyl victims were Black, compared to 21% countywide, according to a Southern California News Group analysis of overdose fatality locations provided by the L.A. County Medical Examiner-Coroner.

Porter, for his part, said he sees a strong connection between institutional racism, poverty and high overdose rates in predominantly Black communities like Skid Row.

“Living in extreme poverty shortens your life span,” Porter said. “There are many people I’ve known and that I’ve come to find connections with, (whose lives were) cut short and there is no accountability.”

The SCNG analysis of coroner’s data found that the majority of fentanyl overdose hot spots are in low-income neighborhoods.

In the 0.8 square-mile ZIP code of MacArthur Park, near Downtown Los Angeles, roughly a third of residents live below the poverty line, according to U.S. census data. That area had 84 fentanyl deaths in 2022 — more than any other ZIP code in L.A. County.

The Skid Row ZIP codes of 90013 and 90014 followed close behind, with 63 and 54 fentanyl overdose fatalities, respectively.

Other key overdose hot spots include Pico Gardens/Ramona Gardens, Little Tokyo/Chinatown, South Central and Hollywood, where poverty levels range from 20% to 27%, according to census data.

A man moves belongings through Skid Row in Los Angeles on Tuesday, November 14, 2023 where fentanyl overdose numbers continue to rise.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

“People use drugs for many reasons and one of those is to treat the suffering of whatever their life situation is,” Goodman-Meza said. “People who are poor and struggling often use drugs and that creates this cycle where using drugs makes it harder for you to make more money and change social classes; then you wind up using more drugs.”

Related reporting on Los Angeles’ fentanyl epidemic:

- Fentanyl addiction fuels underground shoplifting economy in LA’s MacArthur Park

- My fight with fentanyl: Stories from three people battling addiction

- In LA’s fentanyl epidemic, MacArthur Park community bears the heavy burden

- How can Los Angeles combat its fentanyl crisis? MacArthur Park offers clues

People of color are also less likely to access substance use services, such as methadone clinics or residential treatment centers, Goodman-Meza said. This disparity is reflected in fentanyl-related emergency room admission rates, he added.

While Black people made up more than a fifth of all L.A. County fentanyl deaths in 2022, they comprised just 9% of fentanyl-related ER admissions, according to the L.A. County Department of Public Health.

White residents, meanwhile, made up 38% of fentanyl deaths and 43% of emergency room visits, while Latino residents comprised 37% of deaths and 33% of ER visits.

“Are Black people getting services at the same rates as White people, which would include naloxone distribution and access to medication-based treatments for opiate use disorder, like methadone or buprenorphine?” Goodman-Meza said. “The answer is they’re not.”

Recognizing this gap and increasing services while building trust in communities of color, he said, is now more important than ever – if L.A. is to effectively combat its fentanyl crisis.