Map of LA’s fentanyl hot spots reveals where critical resources are missing

The story was originally published by the Los Angeles Daily News with support from our 2023 Data Fellowship.

Darren Willett, director of Homeless Health Care Los Angeles Center for Harm Reduction, checks a man’s low oxygen level after finding him passed out on a Skid Row sidewalk in Los Angeles on Wednesday, December 6, 2023. Willett administered oxygen and stayed with him till his level was normal. The organization is confronting the fentanyl crisis within their drop in center and with their overdose response team.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

Skid Row. MacArthur Park. Hollywood. These are among the several overdose hot spots where L.A. County’s fentanyl epidemic wreaks the greatest havoc.

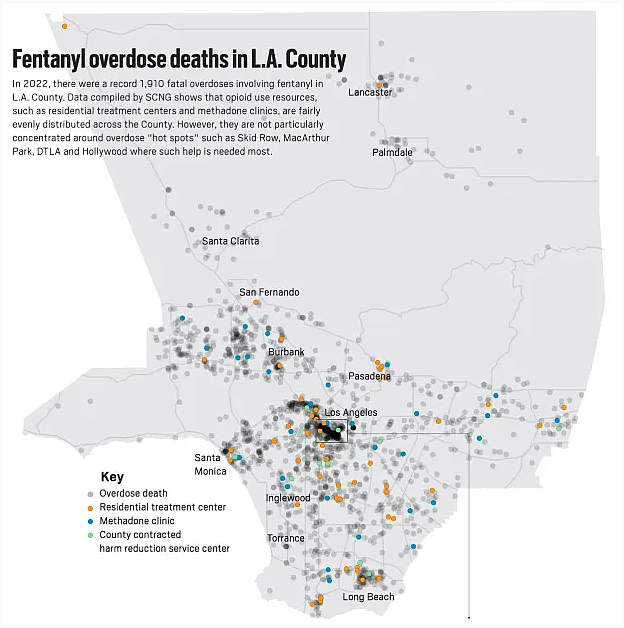

Although the county funnels millions of dollars into addressing the crisis annually, a Southern California News Group analysis of fatal overdose locations and services intended to help found key resource gaps in multiple hot spots.

With the county’s public health department reporting a record 1,910 lives lost to fentanyl in 2022, the stakes of getting the right help to the right places are higher than ever before.

The county’s public health department oversees a vast network of resources. They include 2,765 residential treatment beds for detoxing from drugs; 36 methadone clinics that provide medication for opioid addiction; and 10 county-contracted harm reduction service centers, which provide life-saving resources such as fentanyl test strips and Narcan, a spray that reverses opioid overdoses.

These resources are scattered fairly evenly across the county. Fentanyl overdoses are not.

Approximately 35% of L.A. County’s 2022 fentanyl overdoses took place in just 23 of the county’s 312 ZIP Codes, according to an SCNG analysis of data provided by the L.A. County Medical Examiner-Coroner.

That means just 7% of ZIP codes accounted for more than a third of all deaths.

The greatest number of fatal overdoses occurred around MacArthur Park, an epicenter of fentanyl sales, and in Skid Row, where more than 4,400 people are homeless, according to the 2022 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count. The hot-spot ZIP codes also include Downtown Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo, Chinatown, Pico Gardens and Fashion District, as well as South Central L.A., Van Nuys, North Hills, Downtown Lancaster, San Pedro and Long Beach’s Washington neighborhood.

Despite having more than a third of all fentanyl deaths in L.A. County, the hot spot ZIP codes only have 16% of methadone clinics, 24% of treatment beds, and three harm-reduction service centers.

These data points, though, are an imperfect representation of service availability. They don’t account for mobile outreach teams and local nonprofits, for example, or the fact that some people could travel to a nearby ZIP code to access services.

Nevertheless, they highlight key gaps in the geographic distribution of services.

There is no methadone clinic in Skid Row, for example, despite about 140 people dying from fentanyl overdoses last year. There also isn’t a harm-reduction service center in MacArthur Park, where the 90057 ZIP code recorded 84 fentanyl deaths in 2022 – more than any other ZIP code in the county.

An analysis of where overdoses occur and where the resources are located — coupled with insights from public health experts and people working on the front lines of the epidemic — offer several suggestions for how to better allocate services, including harm reduction, medication and residential treatment.

Harm reduction works in Skid Row, but it is missing in most hot spots

Harm reduction provides life-saving resources – such as sterile drug supplies, fentanyl test trips and Narcan – to everyone who uses drugs regardless of their current interest in quitting. While it is not a new strategy, this approach has only recently been embraced by Los Angeles’ public health officials.

“For decades our philosophy for people who use drugs has been treatment or jail,” said Darren Willett, director of the Center for Harm Reduction at nonprofit organization Homeless Healthcare Los Angeles. “During that time we have funded treatment programming, the criminal justice system and law enforcement and overdose rates have skyrocketed.”

Darren Willett, director of Homeless Health Care Los Angeles Center for Harm Reduction, hands out overdose, wound care and drug kits to people in Los Angeles in Skid Row on Wednesday, December 6, 2023. The organization is confronting the fentanyl crisis within their drop in center and with their overdose prevention and response teams.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

Around 95% of Americans with a substance use disorder don’t access treatment either because they don’t want it or don’t think they need it, according to a survey by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

“That’s why harm-reduction services are so important,” said Gary Tsai, division director for substance abuse prevention and control at L.A. County Department of Public Health, “because we communicate to people who use drugs that we will serve them and we’re there for them, regardless of their interest or lack of interest in treatment.”

Tsai helped launch the county’s Harm Reduction Unit, which currently funds 10 harm reduction service centers.

Homeless Healthcare Los Angeles (HHCLA) is one of them. It operates a longstanding harm reduction service center in Skid Row, which provides a judgment free space for people who use drugs to access food, wound care, sterile drug supplies, overdose reversal kits, medication assisted addiction treatment, case management, areas for rest and more.

In December 2022, HHCLA launched the county’s first ever mobile overdose response team.

Since then the team has reversed 109 overdoses all over Skid Row through its use of Narcan and oxygen, while staff at the center have reversed 46 overdoses. Clients have also saved hundreds of lived using Narcan distributed by HHCLA, Willett said.

“I overdosed and they brought me in here and saved my life that way,” said client Damion Corral. “But then they saved my life in a million other ways because they just have such a positive energy. You can tell whenever they do something it’s coming from the heart.”

“This place saves my life every day, “ says Damion Corral while visiting Homeless Health Care Los Angeles’s Center for Harm Reduction in Skid Row on Wednesday, December 6, 2023. Corral, who was housed after two decades of homelessness, said he travels by Metro from his apartment for the positive energy he says he finds at the center.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

Los Angeles City Councilmember Eunisses Hernandez, who represents MacArthur Park, seeks to bring a similar mobile overdose prevention team and harm reduction service center to the neighborhood, where, she has said, the fire department receives about four 911 calls for overdoses a day.

The challenge, however, comes in convincing residents to embrace a center that caters to people who use drugs.

“There is unfortunately a lot of negative stigma behind drug use. It dehumanizes people and a lot of people don’t see the need for this type of work,” said Aurora Morales, team lead of HHCLA’s Overdose Response Team. “But I know the need.”

Tsai said that combating misinformation and working collaboratively with communities will be essential to growing harm reduction efforts.

“We plan on continuing to expand harm reduction services and continuing to increase the funding for those programs,” Tsai said, “but we recognize that that requires conversations with communities about how we expand in a thoughtful way.”

Robert “Grouch” Steward packs harm reduction kits at Homeless Health Care Los Angeles’s Center for Harm Reduction in Skid Row on Wednesday, December 6, 2023. Steward, a client, is paid to pack kits.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

More methadone in Downtown Los Angeles

While Skid Row has accessible harm-reduction services, there is no place where people can easily access methadone, one of the most effective medications for treating opioid use disorder. Methadone typically needs to be picked up daily and the nearest clinic is three miles away.

“Put a methadone clinic in Skid Row; that’s kind of the lowest-hanging service gap,” said Chelsea Shover, health services researcher and assistant professor-in-residence at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine. “If you happen to live in Skid Row, as lots of people who might need or want treatment for opioid use disorder do, there’s nowhere practical to access it.”

A methadone clinic in Skid Row would also bring treatment closer to residents in the Downtown Los Angeles neighborhoods of Pico Gardens, Aliso Village, Little Tokyo, the Fashion District and Chinatown — all of which were in L.A. County’s top 10 ZIP codes for fentanyl overdoses in 2022.

Making treatment beds ready when people are ready

Residential treatment programs help guide people through the extremely challenging process of detoxing from opioids, provide individual and group therapy and teach strategies for remaining sober.

“I think having more (residential treatment) beds would be helpful, but I also think it goes back to the 95%,” Tsai said, “the fact that the vast majority of people who need treatment, aren’t interested.”

Unfortunately, the extreme pain of opioid withdrawals and high relapse rates discourage many people from entering residential treatment, said David Goodman-Meza, substance use researcher and assistant professor at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine.

“Detox, we know from science, doesn’t often work for the treatment of opiate use disorder,” he said. “If we take 20 people and put them on detox, six months out, about one is going to be illicit drug free. Whereas if you put them on a medication (such as methadone), about 10 of those 20 will remain drug free.”

Rita Richardson, a homeless outreach worker in MacArthur Park, said that the majority of her fentanyl clients drop out of detox by the third day and she can’t get back in contact with them. Richardson leads a street outreach team in MacArthur Park under the L.A. city attorney’s office program LA DOOR (Diversion, Outreach and Opportunities for Recovery).

A person wakes up and leaves a Los Angeles alley in the MacArthur Park neighborhood where people often smoke fentanyl.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

“We go calling trying to look for them, we go back out in the field, but a lot of times we lose them,” she said. “I don’t even know how to fix this unless there was maybe a detox facility in MacArthur Park.”

Despite the low success rates for opioid use disorder, Goodman-Meza said, he still sees benefits in increasing access to treatment beds.

While the county has over 2,700 beds, a lot of them are specialized for specific ages, genders and addiction types and there is no guarantee that a suitable bed will be available when someone decides they are ready for detox.

“The more (beds) the merrier,” Goodman-Meza said. “We should get to a model where if you want to get into treatment, you should be able to come in today.”

His final recommendation was to focus not only on placing more services in hot spots, but also on building trust between service providers and the local community.

“Location is a very important thing,” Goodman-Meza said, “but so is having friendly staff members who don’t think of you as a junkie, but as a human being who has a disease.”