Part 2: My fight with fentanyl: Stories from 3 people battling addiction

This project was originally published in Los Angeles Daily News with support from our 2023 California Health Equity Fellowship.

Jessica, 34, says she would love to get off fentanyl but worries it’s not possible while homeless.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

APacoima man who believes he was born hooked on opioids. A rock music fanatic who sold his late grandma’s house for a fix. A Minnesota native who became homeless at 14.

They are among the many people bound by addiction to MacArthur Park, the sluggishly beating heart of Los Angeles’s fentanyl epidemic.

In any given week, hundreds of people come to the neighborhood to purchase and use fentanyl, a synthetic opioid responsible for 1,504 fatal overdoses in Los Angeles County in 2021, according to the most-recent available data from the county’s Department of Public Health.

For every person killed by fentanyl, many more are living with it. And those who are addicted often find their lives ruled by it.

Fentanyl is 50 times more potent than heroin, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and its “high” only lasts about half as long.

The number of people who buy and sell fentanyl around MacArthur Park has “exploded” in recent years, said LAPD Detective Ben Yi. People often make money to purchase the substance by selling shoplifted goods to some street vendors near the park, said LAPD Detective Stephen Beerer. Vendors resell these stolen items alongside legally acquired goods and homemade food to try and make a living.

Many people who use fentanyl are former pain pill or heroin users, victims of the opioid epidemic that swept across America in the past two decades.

Many live without shelter or teeter on the edge of homelessness. Many have lost family, friends, custody of children, prized possessions, careers and years of their life to opioid addiction.

Here are the stories of three of those people — how they started using, where it has taken them and the barriers they face in breaking free from fentanyl.

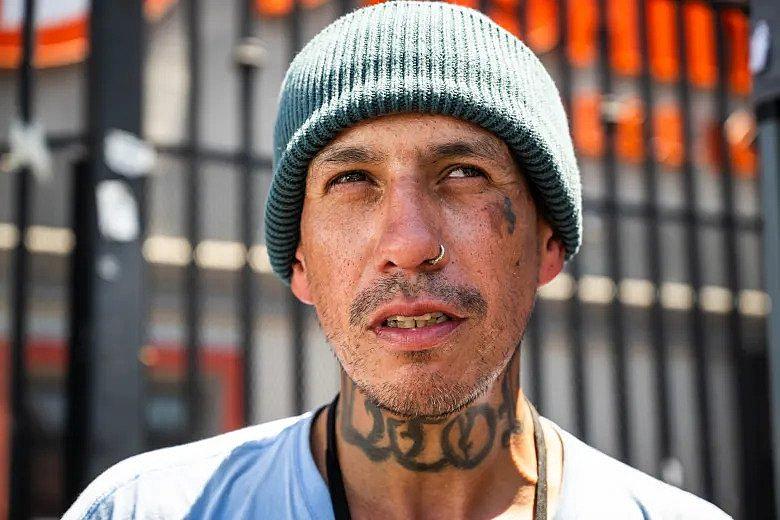

Alejandro, 41, from Pacoima

Alejandro, 41, is getting tired of the hustle to stay high on fentanyl and has begun talking to an outreach worker.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

Alejandro believes he was born addicted to opioids. He said his mother took pain pills while pregnant, so there’s a good chance he was.

Alejandro grew up in Pacoima surrounded by family members who frequently used heroin and pain pills. Opioids were such an ever-present part of his life that he never thought addiction could drive him to homelessness.

Then came fentanyl.

Alejandro and his wife both got hooked about five years ago on pills that they initially thought to be oxycontin — but that Alejandro now believes were laced with fentanyl. Soon they found themselves buying fentanyl directly and eventually needing to smoke every few hours to “get well.”

Chaos in their household ensued. She eventually stopped using and moved with their two children to Las Vegas. He wound up in MacArthur Park in March 2022, where the conditions of homelessness worsened his addiction.

“Cold, hunger, depression, oppression. There are so many things it (fentanyl) helps you deal with better,” he said. “It gets to you, being out here; you see people hungry, you see people dying, you see people having the worst days of their life.”

Alejandro has been living on the streets for 15 months, relying on general relief money and the shoplifted goods market to get by.

He’s also very savvy.

Alejandro fixes a broken pipe with Kyle in an alley where fentanyl use is rampant.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

He knows how to harness an electric scooter battery to charge electronic devices, when phones are distributed outside the LA County Department of Public Social Services, and how to use the IHOP application on said phone to acquire free birthday pancakes.

Keeping a phone is much harder. He has awakened to find his possessions stolen more times than he can remember.

Alejandro is a kind-hearted guy and watches out for many of the younger folks using fentanyl in the area. He’ll offer them advice, watch over their belongings when they sleep and show them how to get free breakfast at the nearby day center run by nonprofit Depaul USA.

After a year and a half of living around MacArthur Park, however, Alejandro is eager to find a way out.

“I’m burnt out and anxious to get back to a greater life,” he said. “But I don’t think I’ll ever be the same.”

Getting off of the streets and getting off fentanyl is no easy feat. Even small tasks can be challenging, such as getting the paperwork to sign up for housing lists or sending emails at the public library.

“Anywhere we go,” he said, “they automatically know that we’re homeless due to our backpacks, or our clothes, or our smell, so it’s extra hard to do anything.”

Beyond that, there’s the need to smoke fentanyl every few hours to avoid withdrawals.

“That’s the biggest hurdle,” he said. “A big part of me getting out is me being ready to get clean again.”

While Alejandro continues to use the drug, he’s charting an escape — motivated in no small part by witnessing the deterioration of those around him.

Cold, hunger, depression, oppression. There are so many things it (fentanyl) helps you deal with better. It gets to you, being out here; you see people hungry, you see people dying, you see people having the worst days of their life.”

Alejandro, 41, from Pacoima

People living around MacArthur Park, Alejandro said, are malnourished, dehydrated and plagued by skin infections. He’s seen friends overdose and die.

“What freaks me out,” he said, “is when I see those people that are gone and they got here the same time I did.

“They appeared normal to me the first time I met them,” Alejandro said, “now there’s no way to help them.”

He’s currently working with outreach worker Jennifer Haid to register for housing. She founded the nonprofit Humankind LA in 2020 to help people experiencing homelessness in MacArthur Park.

“I always knew I wouldn’t be here forever,” Alejandro said, “but for the past two months I’ve really, really wanted to leave.

“Whether I’m ready or not, I can’t wait any longer.”

John, 32, from Antelope Valley, CA

John, 32, who has lived in a temporary housing shelter for over two years, hopes to get his own place and then detox off fentanyl.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

John’s life follows a simple routine.

Wake up and eat breakfast at the shelter on Hoover Street. Pick up a dose of methadone, a medication used to treat opioid use disorder, from the clinic around the corner. Head to MacArthur Park and buy fentanyl or Xanax. Stop by the 7-Eleven and trade food stamps for a peanut butter cookie. Use drugs. Sleep.

When John first came to the shelter, he expected to stay for a few months at most. Over two years have passed. John said he’s no closer to finding permanent housing, substance use treatment or a job than the day he walked in.

He knows he has a lot of work to do to find a landlord who will accept his Section 8 housing voucher before it expires in a few weeks.

But he also needs to procure a large amount of opioids daily in order to avert withdrawals. And once he’s on them, he tends to check out for the day.

“My world is falling apart all around me and there’s so many things I have to do and get done,” he said, “but I’m not doing them because I’m sedated.”

He has already had four housing vouchers expire since arriving in the shelter, he said. John’s eager to get a unit, but doesn’t know how to get in touch with landlords and is afraid they would reject his application once realizing that he’s homeless.

I want out of this. I’m not having a good time. I want my vacation from life to be over.”

John, 32, from Antelope Valley

John gets frustrated by his inability to complete important tasks. He thinks addiction has stunted his development.

“I’m a 32-year-old man; I should already have a wife and kids and go to work,” he said. “It just seems like I’m still a kid, a teenager, a boy-man.”

John started using opioids in his early 20s to numb his anxiety and depression. His use quickly spiraled out of control. He started smoking heroin, and then injecting it. He eventually sold everything he owned to finance his addiction — including the house he inherited from his grandmother.

He was able to stop using heroin with the help of a residential treatment program in Los Angeles, and with methadone. But he struggled to stay off of opioids.

After trying fentanyl, his need became all-consuming.

“I was doing OK for a while staying on methadone, but it (fentanyl) is just so enticing,” he said. “It’s like they made it to be addictive; it tastes good, it smells good, it feels freaking awesome.”

John wants to quit. But he thinks doing so is unrealistic while he lives around other people who use fentanyl.

His dream is to get an apartment unit, check into a rehab program, go home and start life anew.

He’s a huge fan of rock bands like Green Day and Bad Religion and would love to work in the music industry. He said he is also a keen listener and advice-giver and has considered going into counseling.

John modifies his guitar bridge pins with syringe caps. He has played the guitar since his teens.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

“I want out of this,” he said. “I’m not having a good time. I want my vacation from life to be over.”

John’s nightmare is losing his place in the shelter and winding back up on the streets, where he fears his addiction would get worse.

“I really do want to get clean,” he said. “All this (fentanyl) does is bring people down.”

Jessica, 34, from Saint Paul, Minnesota

Jessica, who would love to get off fentanyl, makes her way out of an alley by MacArthur Park.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

Jessica first experienced fentanyl withdrawals on her third day getting high. Since then, she said, much of her life has revolved around pursuing the substance.

“You’re willing to kill your whole family just to get high, you’re willing to kill your best friends just to get high,” she said. “I know it’s messed up; it’s not a good feeling.”

The high, Jessica said, allows her to escape the pain of withdrawals and, temporarily, the “devastating” conditions of life on the streets.

She has been homeless on and off for 20 years — since she was just 14. She came to Los Angeles fleeing a particularly harsh Minnesota winter about a decade ago.

Previously, Jessica used meth frequently, which helped curb her hunger, numb her pain, and fuel her energy while living outdoors. Fentanyl serves a similar purpose and helped break her meth addiction about three years ago.

But it came with its own dangers.

You’re willing to kill your whole family just to get high, you’re willing to kill your best friends just to get high. I know it’s messed up; it’s not a good feeling.”

Jessica, 34, from Saint Paul, Minnesota

Jessica said she has overdosed four times since she started using fentanyl.

Consistent drug use and unsanitary living conditions have taken a toll on her physical health. In June, she said, her legs were swollen with cellulitis and covered in sores from an MRSA (Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) infection, making walking a struggle.

Jessica wakes up in the alley at 5:30 a.m. and bums a cigarette from True. Her belongings are nowhere to be seen.

Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG

Through the pain, Jessica searches for points of brightness. She paints her eyelashes pink, puts glitter on her nails, and enjoys conversations with other people living around MacArthur Park.

During the day, she’ll nap for short periods, often slumped against the wall of the alleyway behind Alvarado Street, where many people smoke fentanyl. At night, she tries to stay awake — and away from danger.

She has made contact with outreach workers in the past, but can’t keep in touch without a phone. And because she comes from out of state, it’s hard to procure an ID to sign up for housing.

Jessica would love to stop using fentanyl in the future, she said. But from her current vantage point in the dark alleyway, it’s a hard possibility to imagine.

“Right now,” she said, “it’s just too much.”