For gang victims, a program aimed at helping and healing

Denisse Salazar wrote this story, part of a series, while participating in the USC Center for Health Journalism‘s California Fellowship.

Other stories in the series include:

With 13,000 gang members in Orange County, the push is on to curb crime and recruitment

Maria Sura visits the grave of her son, Edgar Omar Sura, who was gunned down by gang members in 2012 when he was 20. Police say Sura was not in a gang. More than five years later, Maria says she would not wish her pain on anyone. She visits the Santa Ana cemetery almost daily where she sits and cries. (Photo by Mindy Schauer, Orange County Register/SCNG)

Shortly before sunrise, in the small, dimly lit chapel of a central Orange County hospital, the parents sat numb and motionless – hands clasped, staring down at the floor.

At the other end of a long night in August, their 22-year-old son had been working quietly in his room at the family’s apartment, studying for a class that could help him get a job in the construction trades.

After he’d stepped outside to walk to his girlfriend’s house, they heard gunshots. Neighbors were quickly at the door; their son had been shot several times on the sidewalk.

His mother hurried to the crime scene. She returned home to break the news to her husband and they rushed to the hospital, but they were too late: Their son was dead.

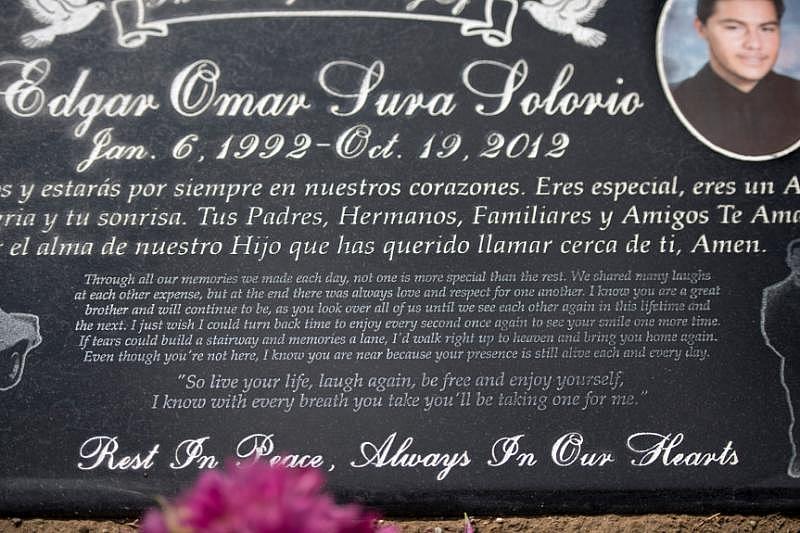

Edgar Omar Sura’s gravestone says in part, “I just wish I could turn back time to enjoy every second once again to see your smile one more time…” His heart-broken parents regularly visit his grave in Santa Ana. (Photo by Mindy Schauer, Orange County Register/SCNG)

Struggling to grasp the jolting change of the last few hours, they awaited the next step, a talk with homicide detectives. When the chapel’s double doors finally opened, two dark-suited men came through. With them was Grace Madueña, who sat across from them. She was the first to speak, calmly and compassionately introducing herself and expressing sorrow for their loss, in Spanish, their language.

Madueña told them she gets summoned by detectives when a gang-related homicide occurs and was there to offer help on the worst night of their lives. She also gave them the name and contact information of the lead detective assigned to solve their son’s killing and encouraged them to reach out to him if they had information about the case.

She offered a list of funeral homes and help applying for financial assistance for victims of crime, and to be a bridge of support to both police and the family’s uncertain future.

“My role is to serve you,” Madueña said reassuringly. “From this day forward, I will be assigned to your case.”

It’s a message she and four colleagues at Gang Victim Services – a federally funded assistance program – have delivered hundreds of times at crime scenes, in emergency rooms and in homes to those coping with the helplessness, fear and anger of losing a loved one to street crime.

On call to detectives 24 hours a day, seven days a week, they often are the first to tell parents their son or daughter is dead. The responses are unpredictable. Some cry. Some turn violent. Some go into a state of shock.

“Emotions vary from family to family,” said Madueña, who lost a cousin in a gang-related shooting in 1991 and experienced the effects on the family first hand. “Everything I do comes from the heart, with a lot of empathy.”

They help families bury their loved ones and hold their hands through court proceedings. They explain whether they’re eligible for state assistance for funeral expenses, relocation costs and mental health treatment.

“Our role is to inform and empower and to be the voice of the victim,” said Michelle Heater, a program director for Wayfinders (until recently known as Community Service Programs), the nonprofit organization that runs the program. “Our advocates are really skilled at explaining to victims that we are here to focus on you and your needs and what is it that I can help you with as your advocate.”

Created during the height of street gang warfare in the 1990s, the program offers a continuum of counseling and other services. They extend from the crime scene, to the burial and any law enforcement investigation – which can span months or decades if the case goes cold – and any court proceedings or later parole hearings.

The goal is twofold: to help the family mourn, stabilize and begin to move forward and aid detectives in developing a cooperative relationship with relatives that can help catch and convict violent criminals.

Surviving relatives also can experience a range of mental health problems, including depression and post traumatic stress disorder, experts say. The advocates serve as a crucial, early connection to mental health services, as well as guides to understanding victims’ rights, said Lita Mercado, who oversees victim assistance programs for Wayfinders.

So far this year, program workers have responded to two dozen gang-related homicides in Orange County and to an estimated 4,000 gang-related homicides since 1990.

The program’s advocates often become a lasting presence in the families’ lives, said Louie Mendez, a supervisor of Gang Victim Services who has worked with victims of gang violence for 24 years.

“They send you thank you cards all the time and emails saying a year from today my son was killed and you were there to assist us and we couldn’t have done it without you,” he said.

Mendez and his team members speak Spanish or Vietnamese and bring cultural sensitivity to the families they serve. They also help with applying for financial assistance through the California Victim Compensation Program, which can help family members pay for funeral expenses, relocation and mental health treatment.

“Every state has its own version of the (financial assistance) program and it has a number of very specific rules,” Mercado said. “One of those is that you must cooperate with law enforcement in order to qualify for it.”

Santa Ana police Cmdr. Eric Paulson, who oversees the department’s division dealing with crime against people, said in some cases the program advocates have been instrumental in helping encourage the flow of information from relatives and witnesses to investigators.

“The detectives trust the advocates with information germane to their cases and the advocates report back the things they hear from their clients,” Paulson said. “This two-way communication, built on trust, is the backbone of our relationship.”

“If you have stable victims who feel safe and supported, they are more likely to cooperate with law enforcement,” Mercado said.

Although gang-related homicides are down sharply since the 1990s – over 70 percent in Santa Ana alone – gang victim advocates say they remain just as busy.

“The number of homicides fluctuates, but the number of victims that we serve remains pretty consistent because we provide services to victims of all gang violence, not just gang homicides,” Mercado said. “We’ve got assault and robbery, vehicular manslaughter, all kinds of penal code violations that occur.”

Funded primarily by two $175,000 federal grants, the program has gradually grown from one gang victim advocate working with detectives in Santa Ana to serve some of the county’s largest cities and law enforcement agencies, including Santa Ana, Anaheim, Buena Park, Garden Grove, Fullerton, Huntington Beach, Orange, Placentia, Tustin, Westminster and the Sheriff’s Department.

Even after a criminal conviction and sentencing of an attacker, family members of those lost to gang violence can find it emotionally difficult to move forward.

Neighborhood children look over a makeshift memorial in Santa Ana where a man was gunned down by alleged gang members recently. (Photo by Mindy Schauer, Orange County Register/SCNG)

That was the case when 20-year-old Edgar Omar Sura was gunned down in Santa Ana in 2012. He was riding his bicycle through a neighborhood when he was confronted by gang members who asked him what gang he belonged to.

Sura, who according to police was not a gang member, was shot in the back as he ran away. He collapsed and died at the scene.

Detectives were able to locate his mother at her work and asked Madueña to come along. Maria Sura was summoned to the office. When she heard the news, she recalled, she couldn’t process what was being said; couldn’t even remember her address.

“I couldn’t believe it until they showed me a picture of my son, Sura said, tearing up as she described her son as happy, polite and friendly with aspirations of working in the health care field. “To this day, five years later, I don’t want to believe he is gone.”

Madueña helped Sura apply for the state’s victim compensation program, which covered funeral expenses and mental health counseling. She also notified Sura and her family when detectives arrested three people in connection with the case and sat with them in the courtroom when the case went to trial.

“It was hard to see those people who didn’t show any remorse,” Sura said, adding that having Madueña to lean on through the grueling and emotionally draining trial gave her strength.

Sura, 53, says her son’s death left her broken. He came home from work at 5:30 each morning. She would be waiting; he would ask for a blessing. She still finds herself there waiting many mornings, she said.

Pictures of Edgar are displayed throughout her apartment and his clothes still hang in the closet. She sleeps with his T-shirt next to her.

Sura says she is still experiencing mental trauma and cries frequently. She has been hospitalized several times, has trouble sleeping and has been diagnosed with high blood pressure.

Frank Gonzalez, a mental health therapist who has counseled family members referred to him by Gang Victim Services, said death from violence can have a devastating impact on survivors, friends, co-workers, classmates and others.

“The psyche can’t handle all of a sudden to hear that your son was shot 10 times at close range or whatever it may be,” Gonzalez said.

Gabriela Juangorena, 24, said her brother’s killing left her shaken emotionally.

“I had a lot of anxiety and panic attacks,” Juangorena said. “I was scared of going out because what if that happened to me too.”

That’s a common response, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. Survivors experiencing post-traumatic stress can have persistent frightening thoughts and memories of the ordeal, sleeping problems, feelings of detachment or be easily startled, the agency says.

Juangorena said Madueña referred her and her mother to a mental health therapist who has helped them cope with the aftermath of the murder. Five years later, Juangorena says she continues to attend weekly sessions and receives medications that have improved her mental well-being.

Her mother agrees.

“It has helped me to move forward,” she said. “But the pain of losing my son will never go away … . It’s a pain that I don’t wish upon anyone.”

Almost every day, Sura visits her son’s grave at the Santa Ana Cemetery.

“When I’m there, I feel peace and tranquility,” Sura said. “I talk to him and read the Bible and I ask him to give me strength to carry on with life.

[This story was originally published by The Orange County Register.]