A Hidden Shelter Provides Refuge to Unhoused Korean Seniors in Los Angeles

The story was co-published with The Korea Daily as part of the 2024 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

A Korean American who lost his sight due to glaucoma is having lunch at a shelter

Sangjin Kim, The Korea Daily

“I, Young Seok, Ji Yoon, Seung Moon, Young Yang, will immediately leave if I ever drink at the shelter.” - September 10, 2019.

“Anyone who wishes to stay in the shelter must make the bed as the first thing in the morning when they wake up. That’s the only rule we have.”

At a shelter, dozens of flower pots are arranged to create a beautiful garden.

Hyounjae Kim

A single-family home near Washington Boulevard and South Gramercy Place, south of Los Angeles Koreatown, is as quiet and peaceful as the century-old neighborhood itself. In the front yard of a home on the corner, dozens of potted plants create a beautiful garden.

“These are the flower pots that Taehong Ahn, who passed away last week, and I took care of," said Father Yohan Kim, 68, a priest at St. James Episcopal Church, describing the neat gardening in the front yard of the house as a kind of “camouflage. "We have to make the garden look nice so we don’t get judged by our neighbors." When rumors swirl about homeless people living in the expensive neighborhood, the city cracks down. "We keep receiving fines, and we could be evicted again," he stressed.

The single-family house is home to 20 Korean-American homeless people. It’s a sanctuary and a community that Father Kim set up to provide food and shelter to 20 elderly Korean-Americans.

Shelters where residents become family

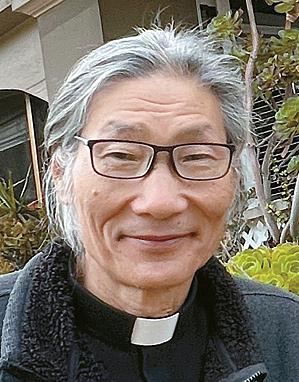

Yohan Kim

Courtesy Yohan Kim

Father Kim first met Korean American unhoused people in 2008 while distributing free meals at his church.

“The first person I met, he said his business failed. He sent all his family to Korea and he jumped off a bridge and tried to die, but he didn’t." Father Kim met a few others and got everyone together. He bought them breakfast at McDonald’s, and asked them what they needed most. "They said they need a bus token because it’s so cold after sleeping on the ground and if they can take the bus in the morning, they can warm up.”

Today, Kim’s concern is the growing number of Korean American homeless people asking for help. “In the past three years, 11 people have passed away at this shelter,” said Kim. “Most of them are old and sick and have lost their ability to work. It is important to help them live with other people in the same situation as much as possible. The best way to do that is to help them spend the rest of their lives while having fun at the shelter.” He mentioned how important it was to feel part of a community, and feel a sense of kinship.

In the mid-2010s, Kim rented a house and began living with 16 Korean-American unhoused people. Since then, Kim has provided food and shelter to more than 150 people. About 40 of them have been able to find jobs and rebuild their lives. His church members and devotees have been supportive of his efforts, but he hasn’t ever received funding from the government, including the city of Los Angeles.

Over the years, Kim and the residents at his shelter have been evicted at least three times after neighbors have complained.

“This single-family house was donated to the church for homeless people by a Korean-American donor in 2019. Initially, we housed up to 30 people, but now we have reduced the number to 20 because we are afraid that the neighbors will report us. Even today I received a call that there is someone who wants to come to the shelter.”

When asked if it will be difficult to raise the $4,000 a month needed to operate the shelter, Kim responds that “with the help of friends, acquaintances, and church members, it’s not a big problem for us to live." He adds that there are still many Korean Americans who sleep in their cars, live in tents or under tarps and keep calling him to come to the shelter.

“Korean American homeless people are afraid of other homeless shelters in LA. I wish we could find more housing where we can keep them together as a family.”

Father Yohan Kim (left) talks with a Korean American resident at the shelter.

Sangjin Kim, The Korea Daily

Kim gives priority for free shelter room and board to Korean-American seniors who are 65 or older and homeless for more than a week. He is also helping about 10 Korean-American people living in tents near Olympic Boulevard and St. Andrews Place in Koreatown. The late Taehong Ahn, who was found dead in the tent camp on the night of April 18, was one of the people who usually helped Kim deliver food and supplies from the shelter to other homeless people in the same situation.

Falling on Hard Times

On April 25, when the Korea Daily visited, the residents in the shelter avoided appearing in the front yard of the house, perhaps conscious of their neighbors. Instead, they spent their time in the backyard garage, which had been converted into a utility room, watching TV, reading magazines, and playing games like Baduk.

At 6 p.m., in the shelter’s kitchen, a group of middle-aged Korean-American men prepared dinner. One senior man in his 70s boiled instant ramen noodles. The kitchen is directly connected to the backyard gate. On the wall above the refrigerator, several handwritten and signed memorandums said, “I will immediately leave the shelter if I drink alcohol.”

Home to 20 seniors 65 and older, this 4,000-square-foot shelter was originally a family home. It had five bedrooms and five bathrooms, including an attic. Kim made three additional rooms by partitioning off the living room to accommodate more people. In a room, two to three people live as roommates, each with a single bed. The common areas, such as the restroom, laundry room, and kitchen, are kept spotlessly clean.

Most of them didn’t want their names and recognizable faces to be known. “We’ve been living together in the shelter for seven years,” said Chulsoo Kim (alias), 67, who occupied the attic on the third floor of the house. “I was working as a construction worker, but I lost my job. Since then, I have no work and no strength. I came here through someone I knew.” Showing signs of illness, Kim said, “I can’t get back on my feet. My credit was ruined and I didn’t have many options.”

Bedridden with a serious illness, one shelter resident watches Korean broadcasting.

Sangjin Kim, The Korea Daily

Robert Song (alias), 67, poured hot water into a rice bowl and made bean paste stew for dinner. “There’s rice in the rice cooker and kimchi in the fridge. Everyone is responsible for their own meals,” he said.

Song came to Los Angeles from Guatemala three years ago. His plans to work fell through, and he lived in a tent on a street near 6th and Catalina Streets in the Koreatown neighborhood. Subsequently, he was fortunate enough to stay at the shelter since January 2023.

“My specialty is in the sewing industry, but when I came to LA, I found that the sewing industry, including the Korean American java market, was dead. I couldn’t find a job because I don’t speak English, I don’t have any status or a driver’s license. Sleeping on the streets is not safe, so I’m very grateful for this shelter.”

Song has a wife and a son aged 22 in Guatemala. He is the only homeless person in this shelter who has managed to find a job. He is saving money as a plumbing assistant currently. “I’ve saved $2,600 so far,” he says, “and I’m going to make it to $10,000 so I can go see my family in Guatemala.” He is determined to make it happen.

This project is supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California,” a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.