This land is whose land?

The story was originally published in 48Hills with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 Data Fellowship.

Dr. Ahimsaa Sumchai shows cancer clusters near the shipyard.

Aided by a USC fellowship, reporter Tom Molanphy and 48hills dug into the overwhelming history of data concerning the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, which has been in clean-up mode since being declared a Superfund site in 1989. With expert guidance from a 2022 Civil Grand Jury Report and a shallow groundwater response to sea-level rise study, the numbers add up to one irrefutable takeaway: the devastating impact of displacement on one of the city’s most vibrant communities. Part One is here; part two is here.

III. The Transfer (1999- present)

With Superfund site status granted in 1989, the Shipyard cleanup kicked into high gear, overseen by the EPA, the Department of Toxic Substances, and the San Francisco Bay Regional Water Board—all managed through the Navy’s BRAC program. Lennar Corporation, which had reaped windfall profits through the 1990’s buying up decommissioned military sites in California like Hunters Point, won the bid to develop the Shipyard in 1999.

Despite growing media attention to the contamination of the Shipyard, led by Lisa Davis’ thorough expose “Fallout” in SF Weekly in 2001 and later Chris Roberts’ reporting at Curbed, the transfer of the land to the city seemed inevitable.

Many longtime Hunters Point residents like Kevin Williams, still carrying around the napkin-value “certificates of preference” of Redevelopment from the 1960’s, were skeptical of the entire process. But the city needed housing, and the initial transfer of Parcel A in 2004—selected because it was as far as possible from most of the industrial, chemical and radiological activity of the former base—was a grand and optimistic event.

“For decades, the Hunters Point Shipyard was the economic engine for San Francisco and for the people — even my own family — who came from the South to work there. Its closure really hurt this community,” Supervisor Malia Cohen told the Chronicle in 2015 when housing units were finished on Parcel A. “It’s going to take a lot of work and a lot of money to continue to move down the right path, but what we are seeing now is a renaissance. We are turning it around, like a phoenix rising up from the toxins.”

The toxins—and allegations of fraud—soon overtook that rise. “By the time the cleanup plans were documented for the parcels beyond Parcel A…unrestricted use was out of reach,” the Civil Grand Jury report states. “In many areas, new buildings would be required to be fitted with special equipment to divert poisonous vapors away from their interiors.”

As challenging as an honest cleanup would have been, problems with a Navy contractor only made activist chants of “Clean Up not Cover Up!” louder. A series of Chronicle investigations revealed the level of exposure to police employees housed in Building 606 and internal e-mails from the Department of Public Health indicating that they used helicopter radiation scans because they knew it would turn nothing up.

Meanwhile, a Stanford-trained Hunters Point physician who had tried to warn San Francisco about the hidden dangers of the Shipyard for decades could only shake her head.

***

While staffing a monthly Open House at her Hunters Point Biomonitoring Foundation Clinic on Third Street, Dr. Ahimsa Sumchai dotes on her Romeo. The 2021 UCSF Alumna of the Year is as serious as you’d expect the first female African-American flight-physician on emergency helicopter transports to be. But she shows her soft side with her Pomeranian who just tore his ACL.

When the Shipyard cleanup is brought up, though, she’s back to business.

“That’s our cancer cluster,” Sumchai says, pointing out different clusters of pins on her whiteboard map, her favorite prop at the innumerable Shipyard protests she’s attended over the years. “This is Crisp Road. And then this is the Western fence line. The cancer cluster runs along the western fence line all the way down to Yosemite Slough.”

With the portrait of her mentor Carlton B Goodlett behind her, Sumchai’s relentless campaign to reveal the true toxicity of the Shipyard draws inspiration from her youth gymnastic champion days—small but mighty, capable of absorbing falls and getting right back up.

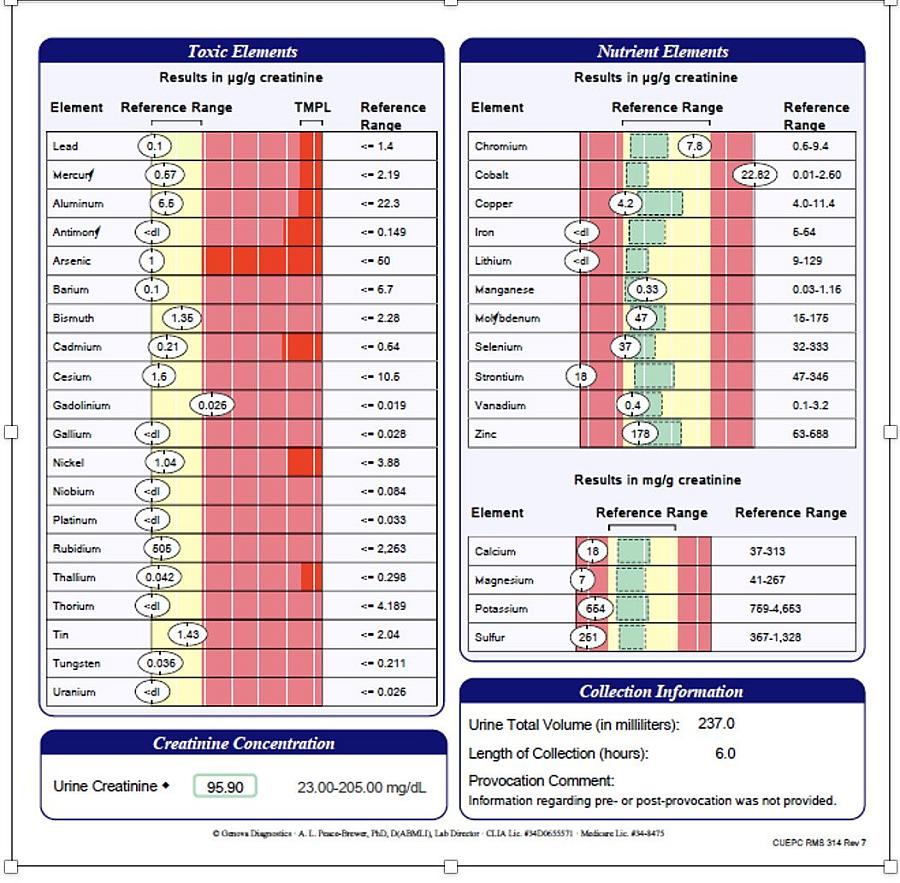

“We’re documenting the adjacency issues of people in proximity of three federal Superfund sites,” Sumchai says about the work of her clinic. “We tested someone who lives on Kiska Road behind the naval laboratories, close to the shoreline. And her arsenic and thallium levels are off the chart. It just makes me want to cry when I get a result back like that. Someone who’s got dangerous rat killers in their system at toxic concentrations.”

Example of a biomonitoring result from Dr. Sumchai’s clinic.

When she’s certain about her conclusions, such as what should be done with problematic Parcel E-2, she sticks her point as forceful as a gymnast’s landing.

“The landfill should be walled off. There’s radiation pollution down several feet. And then there’s all kinds of radiation in the water. There’s absolutely no way they could dig it all up.”

Sumchai also makes it clear her responsibility isn’t to propose land use. Her responsibility is to public health.

“I personally am not here to be a proponent of different methods of reuse. It’s a very, very dangerous area. I took the Navy’s data and in a presentation to RAB (Restoration Advisory Board) concluded that Parcel A was not suitable for transfer.”

Sumchai knows the Shipyard backwards and forwards; her voluminous writing and research on the Shipyard is outsized only by the Navy’s. She’s fully versed in the contamination that “Operation Crossroads” brought back to Hunters Point, made personal when she signed the death certificate of her father, a career longshore-walking boss and shipping clerk at the Shipyard, who died in his early 50’s from pulmonary asbestosis.

But Sumchai understands better than most that “Operations Crossroads” signified a crossroads for all of the humanity; the bomb had been dropped and the world was forever changed. The Navy wanted to understand what kind of world they had created, and Ahimsa traces her pointer on the map to the result of that curiosity: the Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory.

What “Operations Crossroads” had haphazardly started, this white, windowless, six-story building completed in 1955 would attempt to finish by exposing countless animals to the biological effects of radiation, inducing skin burns, gastrointestinal damage and effects on the central nervous system.

“The Shipyard is a very, very complex situation, and it does require a lot of advocacy,” Sumchai says. “I am hopeful that the work that we’re doing will bring about some changes. But I can’t help but reemphasize that people are being actively exposed.”

It’s hard to track at times who’s in charge of the cleanup.

And who is in charge of the Navy always seems to be, the Navy. “The Navy’s sovereign immunity is what is the issue,” Sumchai says. “And the Navy is the lead agency in the clean-up.”

As angry as Sumchai is with the Navy’s handling of the clean-up, she understands what the Navy’s economic presence helped create. She’s well aware of the Harlem of the West heydays.

“My grandparents were upper middle income, the first African Americans to own a three-story house on Teresita Boulevard under Mount Davidson in the 1960’s. My grandfather and my father were career longshore men.”

Workers at the Shipyard, 1949.

Photo from FoundSF

And she emphasizes that the Shipyard required not just hardhat work but the lab work of academics and researchers. She points out a stretch of buildings on her whiteboard.

“You could think of Bayview Hunters Point and the Third Street commercial strip being very much like a Berkeley in terms of the impact of the NRDL campus laboratories. If you just follow Crisp Road, and then enter the Shipyard, all of those 800-series buildings were our campus, which was like the best and the brightest, from 1946 to 1969. Top researchers like Jannette Sherman.”

Another of those “best and brightest” shines through in the Final Historical Radiological Assessment of Hunters Point Shipyard, which Sumchai helped produce. Tucked in the back of the 665-page study, after vital but largely indecipherable chapters like “6.1.2 Gamma Radiography” or “7.3.4 Potential Migration Pathways,” Cynthia “Neil” Gruszkiewicz described her experience as a Bacteriologist in the Bio-Medical Division of the NRDL from 1961-1964. Gruszkiewicz’s assessment of the NRDL may only strengthen the suspicions of environmental activists today:

When pushed again for what should be done with the Shipyard, ultimately, Sumchai pushes back.

“Again, it’s not my job to propose land use. We need doctors like myself and Dr. Dahlgren who are willing to break with the party line from this corruption. That is, if it all ends, like it ended in Flint, Michigan.”

When confronted by the common refrain about cancer clusters in the Bayview, namely that there are so many possible toxic sources that all sources, in effect, get off without consequences, Sumchai shares a specific contaminant they are testing for.

“We are detecting plutonium. That is 100% specific to the Navy as the polluter, and the Shipyard is the source of the pollution. Dr. Dahlgren detected plutonium in 9 out of 11 screenings this summer.”

“They’re not going to be able to write that off.”

***

Café Alma—an open-air coffee shop loaded with treats and patrons on their laptops—could pass for any café in San Francisco. The difference is that Dr. Katherine Higley flies down from Oregon State every few months, sits at a corner table with her tea, and tries to calm residents’ concerns about living next to one of the nation’s worst Superfund clean-up sites.

“From a scientific statistical point of view, I take some exception to the work that’s being done,” Higley, looking comfortable but professional in a black windbreaker and jeans, says about Dr. Sumchai’s work at the biomonitoring clinic. “You have to be able to link in the exposure and an effect. Basically causation.”

Katherine Higley at Café Alma

In short, she argues, Hunters Point has too many guns pointed at it to tell which one is smoking. The science of cause and effect reduces people to data points, a necessity for accuracy but a method as cold as thousands of pages of Navy records.

“How do you know that what you see in their urine is reflective of exposure from that site versus exposure from anywhere else that they have been?” Higley asks. “Or other aspects of their environment? You have to go through a process to tease that out. That’s the challenge of bio monitoring, without having some sort of control.”

As far as the smoking gun theory on plutonium that points directly at the Navy as the culprit, Higley is skeptical about the plutonium results.

“Plutonium typically is not easy to detect. And if you’re simply looking at alpha radiation, there are a whole bunch of other naturally occurring radionuclides that emit alpha particles that aren’t plutonium. And unless you make an effort to try and tease that out, I’d say, you’re getting over your skis, right?”

“The other thing is that probably a third of us are going to get cancer, or multiple cancers. That’s just the nature of humans living as long as they do. And probably a quarter of us are going to die from cancer. What fraction of those are environmentally caused versus, you know, random chance is a bit of a debate.”

When asked about getting the Shipyard to Prop P level residential-clean levels, Higley focuses on how much exposure is too much, not how much toxicity is buried. If residents aren’t exposed to whatever risk is there, does that risk matter?

“How clean is clean enough? That’s kind of the big question.”

This sidesteps the main thesis of 2022 Grand Jury, namely that “buried contaminants that are now dry and stationary could become wet and mobile.” And it only takes a few minutes of toggling around SFEI’s new ART Bay Shoreline Flood Explorer to chart the likelihood of sea-level rise at the Shipyard making contaminants mobile.

A particularly concerning mobile contaminant to the Civil Grand Jury are volatile organic compounds, like the “swimming pools of solvents” mentioned by Carter.

“And VOCS have a superpower,” the Civil Grand Jury report explains. “Where sewer lines have been damaged, water carrying VOCs can leak into the sewers. Toxic vapors can then rise off that water and travel up the pipes…into a large number of bathrooms and sleeping areas (of the planned residential buildings at the Shipyard.)”

“My focus is mainly radioactivity,” Higley says. “By and large, there are some small spots of activity, but the bulk of it, to me, is not substantially contaminated. The likelihood of seeing an impact in the community on a large scale just seems really, really, really, remote to me.”

Higley cites Hiroshima and Nagasaki, inextricably linked to the Hunters Point Shipyard since components of “Little Boy,” the bomb that contained half the world’s know enriched uranium at the time, left Hunters Point Naval Shipyard on July 16, 1945, to be dropped by the Enola Gay on Hiroshima on August 6.

“We’ve known about radiation for nearly 150 years, right? We’ve been really studying its effects for about 100. Plus, we’ve been doing really in-depth research on populations that have been exposed to radioactivity. There’s a Radiation Effects Research Foundation that posts all of their analyses.”

Customers tap on keyboards, drink coffee, eat scones. Is it reassuring that they don’t have to worry about Hiroshima levels of radiation here?

Higley said she is game to consider the broader socio-economic questions surrounding the Shipyard, how longtime residents whose grandparents toiled there have been forced out by either legacy redlining practices, toxicity issues, or a mad mixture of both. Whose land is it, and, if it can be made safe, who gets to stay?

“No, I get that. I think people are starting to pay a little closer attention to those particular issues that this was built on the backs of people. What are your obligations to them?”

“That’s the issue of equity. That’s a way broader question that I think our society really needs to deal with.”

***

Floating over Parcel F and thinking about equity, MLK’s 1963 Civil Rights dream that “justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream” comes to mind. The 20 inches of rain that rolled down on San Francisco— and the Hunters Point Shipyard—this past winter was a mighty stream that revealed, once again, how poorer communities take the brunt of catastrophes. Same storm – different boats.

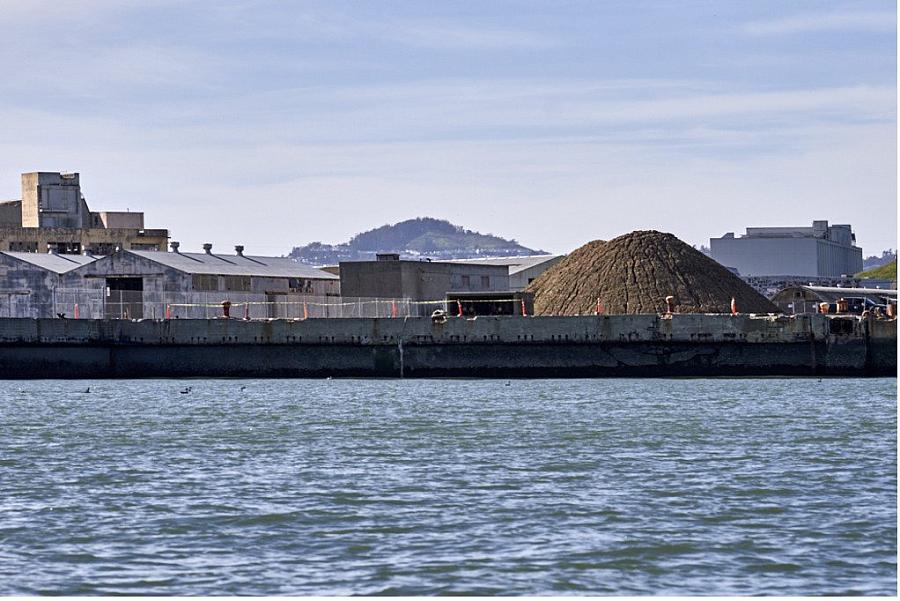

After winter storms, the Navy explained how straw wattles and sandbags would help prevent dirt piles like the one pictured above from washing into the Bay. Straw and sand will not adequately address the groundwater concerns of the 2022 Civil Grand Jury Report.

Photo by Ebbe Roe Yovino-Smith

What will ultimately become of the Shipyard will not be decided for years. There are several lawsuits in play, and the city will hold many more meetings, like the October 6, 2022 meeting that featured emotional public testimony from many local experts, including Dr. Sumchai.

At that meeting, Dan Hirsch from Committee to Bridge the Gap echoed the outrage of several speakers that the EPA had decided not to clean the Shipyard to Prop P residential standards. Dr. Kim Rhoads of the UCSF Cancer Center emphasized the disproportionate levels of leukemia in Hunters Point compared to the rest of San Francisco, and that “this distribution of leukemia will persist as long as the contaminants persist.” If the site is not cleaned to residential standard levels, the experts pressed San Francisco to refuse the land transfer altogether.

Many environmental justice activists, emboldened by the new office of the EPA on environmental justice, hope progressive San Francisco sees the Shipyard as more than just a real-estate deal. Not only as an opportunity to correct past mistakes of redlining, but to better prepare everyone for the challenges of climate change.

Charles Oppenheimer, whose grandfather built the bomb carried from the Shipyard (and whose life will be on the big screen in July,) said he hopes we can point our substantial resources towards that climate change challenge.

“Reaching a commensurate level of urgency and funding against climate change as the Manhattan Project would be a start,” Oppenheimer wrote in an SFGate.com op-ed. “That project cost about $34 billion in today’s dollars. Today, we spend $60 billion annually in the U.S. on nuclear weapons. There is plenty of room for prioritizing things that make the world better, not worse.”

If the Shipyard as a means for climate justice or reparations seem impractical for a city budget, some experts suggest San Francisco might consider saving itself. Plowing ahead Miami Beach-like with more shoreline housing may only set up the city for more lawsuits. “This incomplete cleanup will leave the site locked in litigation for many years to come,” Jeff Ruchs of PEER argued in his direct plea to Nancy Pelosi.

The wind picks up behind me, and I turn the kayak towards my berth at India Basin. Cutting through the chop is a reminder that the waves will not stop coming. And that the rising tide will not stop its work of uncovering the truth.

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.