Part 1: The tragic toxic legacy of the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard

The story was originally published in 48Hills with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 Data Fellowship.

Drydocks and Point Avisedero in background.

Photo via FoundSF/US Navy

Aided by a USC fellowship, reporter Tom Molanphy and 48hills dug into the overwhelming history of data concerning the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, which has been in clean-up mode since being declared a Superfund site in 1989. With expert guidance from a 2022 Civil Grand Jury Report and a shallow groundwater response to sea-level rise study, the numbers add up to one irrefutable takeaway: the devastating impact of displacement on one of the city’s most vibrant communities. Below is part one of our three-part series

I. The Base

The swell that lifts my kayak in San Francisco Bay has changed little in thousands of years. Where it’s headed— and what it’s lifting—has.

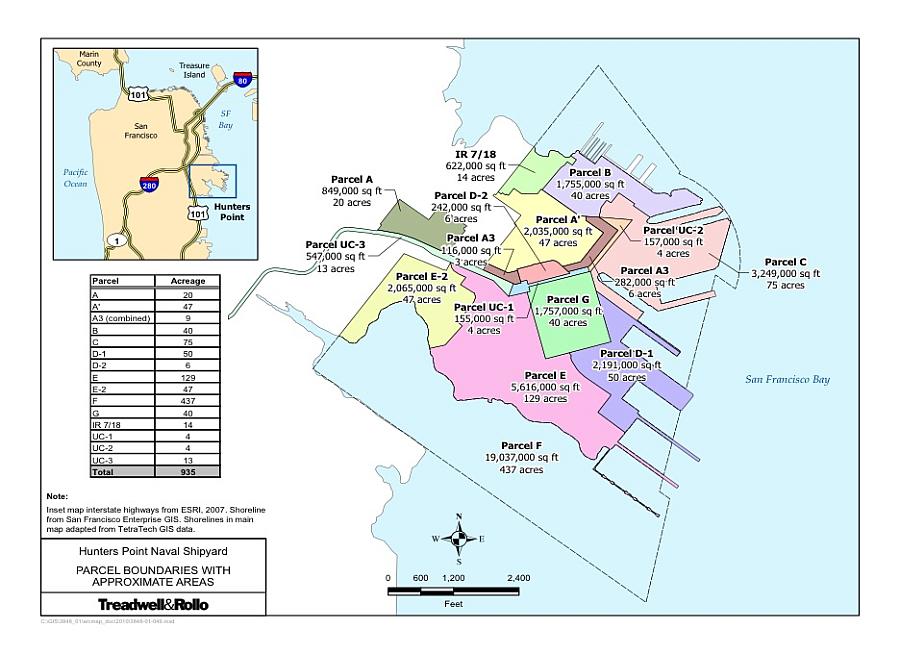

I’m floating between Drydocks #6 and #7 on Parcel F of Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, 437 underwater acres the Navy promises to make safe by 2027. For thousands of years, Ohlone waded barefoot into this tidal wetland area to grab dinner raw off the rocks. Today, the owners of the boxy Lennar condominiums that ledge the horizon like Legos are warned that gophers could tunnel radioactive waste into garden beds. It’s a different landscape.

Although the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard clean-up has made news ever since the Navy closed the base in 1974, the 2022 Civil Grand Jury Report, “Buried Problems and A Buried Process,” recently backed-up by a “Shallow Groundwater Response to Sea-Level Rise” report in January, have raised new concerns.

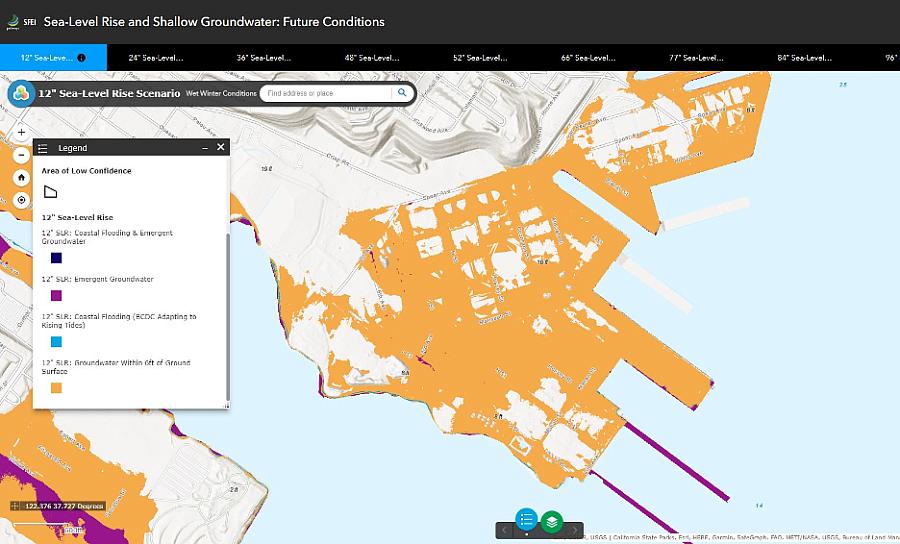

Unlike much of the previous analysis of the Shipyard, decades of research as mucky as the Bay mud I’m floating over, the 2022 report focused specifically on how sea level rise affects groundwater rise—and what that rise might push to the surface.

“What could go wrong during an extreme precipitation event at the end of a wet winter, supercharged by climate change and rising tides, when the ground cannot hold any more water?

The intersection of rising ground water and buried contaminants poses a credible risk to human health and well-being.”

A map of the contaminated parcels at the Shipyard compared with a projected 12” sea-level rise scenario reveals how close contaminated groundwater may come to the surface

Though the Mayor’s office disputes the report, and the Navy pledges that any complications will be further addressed in their “Five-Year Review” due in Fall of 2023, there’s no debate that the billion-dollar cleanup of this toxic site remains a mess. What’s being debated is how much toxic and chemical waste can be safely left behind.

A map of the contaminated parcels at the Shipyard compared with a projected 12” sea-level rise scenario reveals how close contaminated groundwater may come to the surface

And what waste should be left in Hunters Point, unfortunately, is not news for this community, who have had to bear the wastewater, industrial toxins and garbage from the rest of San Francisco for generations. Over those many years, the community that surrounds the Naval Shipyard have consistently pleaded for the rest of San Francisco to recognize their neighborhood as more than a place to flush their water, dump their trash, and spew their toxins.

Such recognition will depend largely on the willingness of the rest of San Francisco to consider the full story of the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard. Only then can a just reckoning with the Shipyard take place.

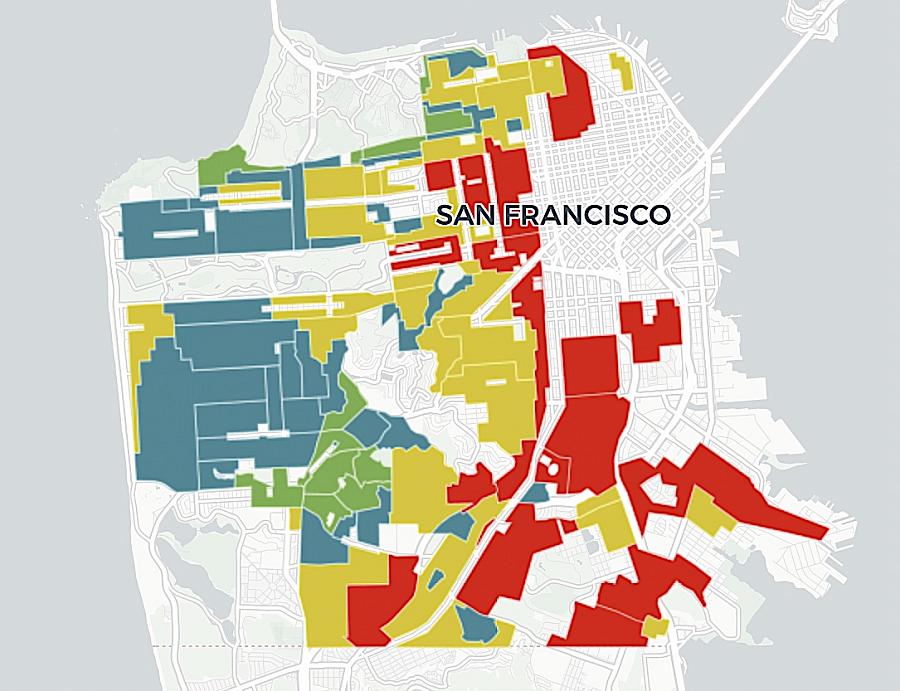

A map from the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project shows redlining in San Francisco.

***

The first thing to know about the land of the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard is that most of it isn’t land at all. Although the California Dry Dock Company built a 47-acre ship repair yard at Hunters Point in 1868, it was the threat of war in 1939 that compelled the US Navy to buy the site for a massive expansion. The Navy needed more shoreline, and it wasn’t about to wait around for the serpentinite-matrix mélange of the Hunters Point Shear Zone to comply.

170-foot Point Avisedero was pulverized into five million cubic yards of earth, which was then dumped into the Bay and spread out to create the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard we know today. The Civil Grand Jury Report highlights this crucial moment of creation, a birth of “land” that offers “a junk drawer full of problems.”

“Fill soil like that in the Shipyard is at high risk of liquefaction during an earthquake, and rising groundwater can increase the likelihood and severity of liquefaction. Setting aside earthquakes, when groundwater rises and encounters an impermeable surface like pavement, the foundation of a building, or a sewer line, the water pushes up on it as if it were a boat.”

David Johnson at his home.

The Navy cranked up operations once they had “land” to work with. In the span of seven years, between 1939 and 1946, sixty buildings were constructed, 199 ships repaired, and over 12,000 housing units built.

As dramatic as the physical change to the landscape was, that was just the opening act. The draw for workers at West Coast military bases like Hunters Point – coupled with the repugnance of Jim Crow laws in the South – created the epic tide of the Great Migration that would change San Francisco forever. In just one year, 1945, the African American population in Bayview Hunters Point increased by 665.8%.

David Johnson, ‘Boys and Flag,’ Hunters Point, undated.© The Regents of the University of California, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Due to redlining practices, most African-American moved into the Fillmore, which had a high vacancy rate since Japanese Americans had been evicted and sent to concentration camps. With good-paying jobs at bases like Hunters Point, the newcomers had the means to establish a vibrant culture in the Fillmore, creating the iconic “Harlem of the West.”

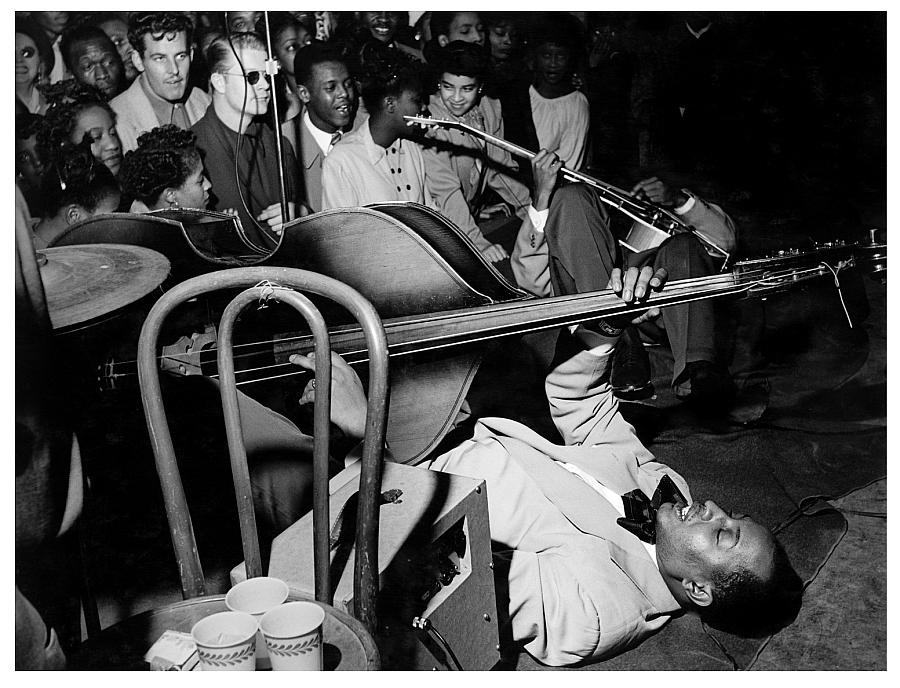

And a young African American photographer from Florida, invited to San Francisco by Ansel Adams, was there to capture it all.

The best way to get to David Johnson’s home from San Francisco is by ferry, then foot. The 40-minute ride from the Embarcadero to Larkspur reminds passengers that the Bay Area is like the human body: dominated and defined by water. The journey allows time to review Johnson’s “Harlem of the West” collection, the definitive history of how San Francisco was transformed by the Great Migration before and after WWII. And the 30-minute walk along the bay to his home allows time for that work to settle in, to the point that meeting the man himself beats a thousand photographs.

“Lucky was looking for me,” Johnson says. “He’s like, come here, you’re going to California. And you’re going to learn photography.”

David Johnson, ‘Bass player Vernon Alley,’ 1948. © The Regents of the University of California, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Johnson’s 96-year old stare remains as alert as a camera, his blinks like snapshots. Sitting comfortably in a red sweatshirt, black slacks and white cap, Johnson recalls being a 20-year old WWII Navy veteran living in Jim Crow-Florida. He happened upon a magazine ad about a new photography school in San Francisco, a city that stole his heart when he was briefly stationed there. He scrawled a letter to the director, one Ansel Adams, in 1946, petitioning to join the new photography department at the California School of Fine Arts (now SFAI.) Adams accepted him.

“People from all over the world came to California. And I was there with the camera. I don’t think we realized that we were the Great Migration. We were just going to places to get jobs.”

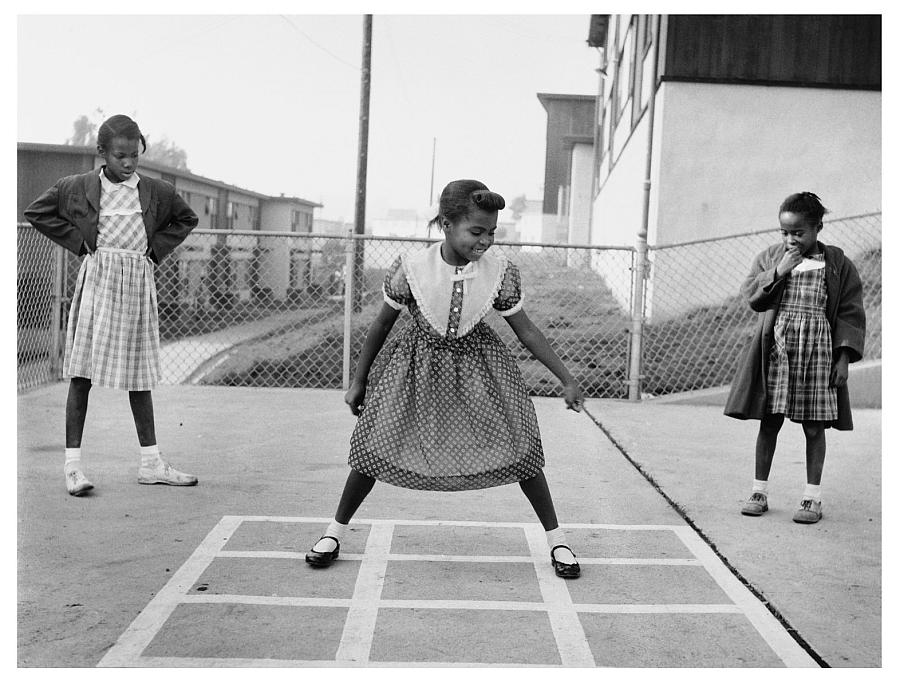

David Johnson, ‘Girls playing hopscotch, Hunters Point,’ undated. © The Regents of the University of California, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

According to Johnson, the Fillmore’s relationship to Hunters Point Naval Shipyard was direct: one could not have existed without the other. Jobs at bases like Hunters Point gave workers stability; the cultural transformation of the Fillmore gave people reasons to live.

Jackie Sue Johnson, Johnson’s wife and author of his biography A Dream Begun So Long Ago, sits calmly by his side and minds his story. She emphasizes that the story of the Fillmore and the Shipyard is the repeated story of American migration.

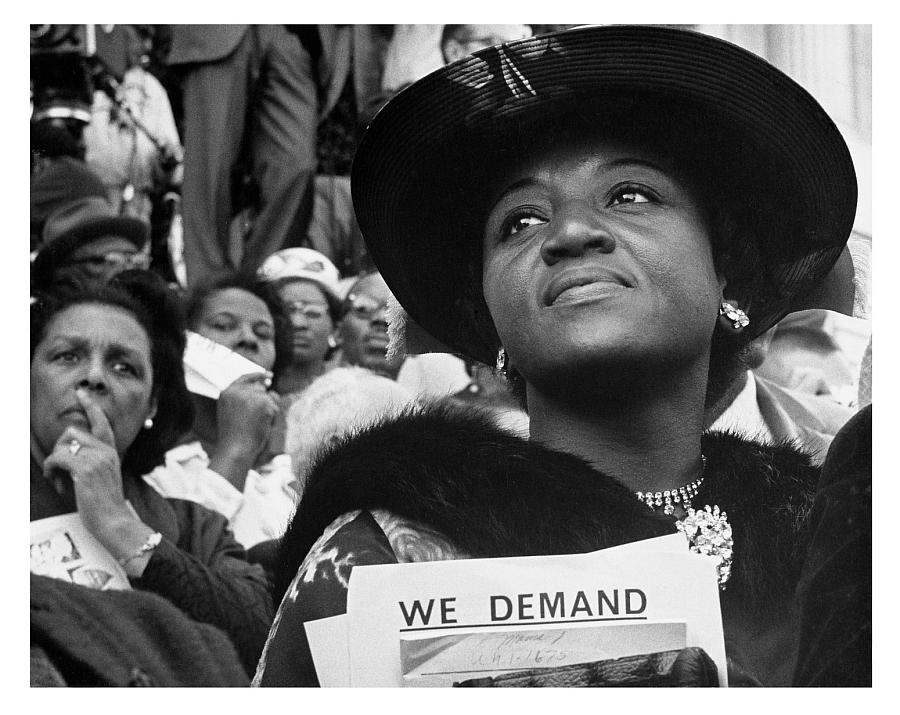

David Johnson, ‘”We demand.”‘ Civil rights demonstration, San Francisco, 1963. © The Regents of the University of California, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

“There were two things that occurred,” Jackie Sue Johnson says. “One that the Japanese were put into the concentration camps, which left a vacuum for African Americans to fill. And then the African Americans brought their culture.”

And what a culture it was. The African American contributions to San Francisco are just as impactful as other migration waves such as the original 49ers, Beats, Hippies or Techies. Johnson describes that impact in the Fillmore in A Dream Begun So Long Ago.

Ruth Williams leading a protest at SF State University in 1966.

Photo via KQED

“The jazz scene with the visiting musicians at the Primalon Ballroom, the Booker T. Washington Hotel, the Texas Playhouse, the New Orleans Swing Club and the Flamingo Club are my favorite places to capture the nightlife of the city. I take my twin-lens reflex film camera and photograph the musicians and singers as they perform. In the ’40s and ’50s, the Fillmore District was the hot spot in San Francisco where entertainers came to ‘jam.’”

Johnson’s alert eyes rove around the room, still inspired by those shots. “The things that interest me are, how are people being treated? Why do you do what you do? That’s wonderful. Not just about me and a few dollars, but how can I improve the world that I believe in?”

Photo of “Girls playing Hopscotch, Hunters Point, 1946” by David Johnson:

Timing in photography can be everything. Johnson timed not just one good photo but years of photos throughout the joyous fifties and into the convulsive 1960’s. Well-aware of his own story – a young African American who grabbed opportunity with both hands – the importance of equal opportunity led Johnson and his camera straight into the Civil Rights movement.

“David will talk to you about photography all day long,” Jackie Sue Johnson explains. “But he will never say what he did in the Civil Rights era.”

Those accomplishments could fill an entire photo catalogue. Johnson helped to unionize the US Postal Service; founded the Black Caucus at UCSF; led the Haight Ashbury Merchants Association; and in 1970, he brought a suit against the SF Unified School District and won a landmark case for integration for the city’s schools.

If the Fillmore years in the 1950’s brought the highest of highs, Redevelopment through “Urban Renewal” in the 1960’s brought the lowest of lows. Bulldozers leveled the prized-Victorians that many African-Americans rented (or even bought) with their wages from bases like the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard. Another migration began as the African American Fillmore community was pushed into substandard housing by redlining practices that created the Bayview “sacrifice zone” and health hazards that continue to this day.

The injustice of Redevelopment would lead to a power to the people movement in San Francisco, led by the iconic “Big Five” of Bayview Hunters Point.

***

Kevin Williams looks at home in the Bayview’s Old Clam House. Sporting wrap-around sunglasses and an easy smile, he navigates through San Francisco’s oldest continuous restaurant, 161 years, to the sunny veranda. After enjoying the signature clam juice, Williams lays out photos and records of his mother’s work. While David Johnson documented the peak of the Fillmore, Ruth Williams, part of the Bayview’s “Big Five,” battled the fallout from Redevelopment.

“I don’t know if you have ever seen this 26-minute video called Point of Pride,” Williams says after ordering the house clam chowder bowl. Along with James Baldwin’s Take this Hammer and Kevin Epps’s Straight Outta Hunters Point, Point of Pride documents the painful economic and social fallout for many African Americans in San Francisco due to “Urban Renewal” in the 1960’s (described as “Negro Removal” by Baldwin.)

Williams picks up the story from Johnson: the engine that had generated stability and the promise of generational wealth in the Bayview sputtered as work at the Naval Shipyard dried up. That weakened the cultural life of the Fillmore, and Redevelopment delivered the knock-out blow.

Williams shares the familiar American story of economic and social injustice leading to economic and social unrest. In 1966, Hunters Point protests were sparked when a white officer shot a Black teenager in the back while fleeing a crime scene, which in turn inspired Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in Oakland to found the Black Panthers and state their “10 Point Program.” The incident also led to a groundswell of protests that Ruth Williams, an associate professor at San Francisco State University, helped lead.

Ruth Williams knew the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard were important to the community. No one disputes that what remains of the Shipyard is a toxic mess. But what’s often forgotten is how much of an economic engine it was for so long for so many. With WWII over and the Korean War winding down, the idea of closing the Shipyard arose in the late 1950’s; by and large, the Hunters Point community rallied against it.

“There was a huge controversy regarding closing the Shipyard,” Williams says. “That’s what led to Senator Robert Kennedy coming to the Bayview Community Center on Third Street. They weren’t really conscious of what would happen once the Navy abandoned the place.”

What hit the community before the Navy closed the Shipyard was Urban Renewal, which went into overdrive for San Francisco in the 1960’s. Even the major architect behind the plan, Justin Herman, whom iconic Sun Reporter editor Thomas Fleming dubbed the “arch villain in the Black depopulation of the city,” prophesized how badly things could turn out.

“Without adequate housing for the poor, critics will rightly condemn urban renewal as an ‘and-grab’ for the rich, and a heartless push-out for the poor and nonwhites,” Herman said.

Many in the Black community, including members of Ruth Williams family, were given “certificates of preference” that entitled them to new housing. Williams laughs at what those certificates promised. He still has one at home.

“That certificate is worth this much,” he says, holding up his napkin.

The certificate program, begun in 1963, was a key incentivizing tool for Herman, allowing an increased demolition from 25 buildings per month in the Fillmore to 40.And the most popular area to send displaced residents from the Fillmore was Bayview Hunters Point, where the “preference” option was 1300 units of hastily rehabbed temporary wartime housing that had been previously declared unfit for living. The environmental injustice that befell African Americans during these years was included in the Civil Grand Jury Report.

“After the war, racist housing policies blocked Black workers and their families from moving to safer, less polluted parts of the City, so many stayed in the shadow of the Shipyard.”

When the 2022 Civil Grand Jury Report is brought up, Williams can only shake his head.

“When I read it, I said, ‘Wow.’ The environmental racism could affect the entire city. The water tables rise, earthquakes, liquefaction, release of all that’s been buried. You can’t just cap or cover it with concrete and clay.”

Williams has seen the Shipyard issue from various sides. Not just as a concerned Hunters Point resident, but also from within the political machine that has tried to build housing there for decades. He worked on the Human Rights Commission and even for the Redevelopment Agency for several mayors, including Willie Brown and Ed Lee.

“Did you read the article in the Standard? Yeah. I have known Willie Brown my whole life. He was my idol.” That idolization led Williams to enter politics as a young man. “Mother told me don’t do it. I should’ve listened to my mother.”

Williams retired from politics in 2004 and is still fighting legal issues with the City. He does not regret his whistleblower activities, despite the personal and financial costs. “There are certain principles that I learned from my mother that I had to protect and defend. Because if you don’t stand for something, you’ll fall for anything.”

When asked if the construction of residential housing at the Shipyard has so much momentum and political clout behind it to render it inevitable, Williams looks up from his clam chowder.

“I might as well hand you the staff of Moses. Listen, you just hit the nail on the head.”

“Who could rationalize them building there, but that is precisely what they’re going to do. The City is going to ignore the recommendations of the Civil Grand Jury. The City will ignore the people it has ignored all these years.”

Williams reflects on how his mother might handle the Shipyard cleanup issues of 2022, keeping in mind that the African American community in Hunters Point is much smaller and more divided.

“Because gentrification has had such an impact, we don’t have the numbers of protesters now. The emphasis ought to be on what we breathe, the environment that we live in, but there’s too much day-to-day survival, high rents and unemployment, you know. So you have a lot of these day-to-day factors.”

His mother continues to inspire him every day.

“I can’t help but do what she told me to do. She said, “All I want, son, is to be remembered.’ And I said ‘Mother, you will be remembered.’”

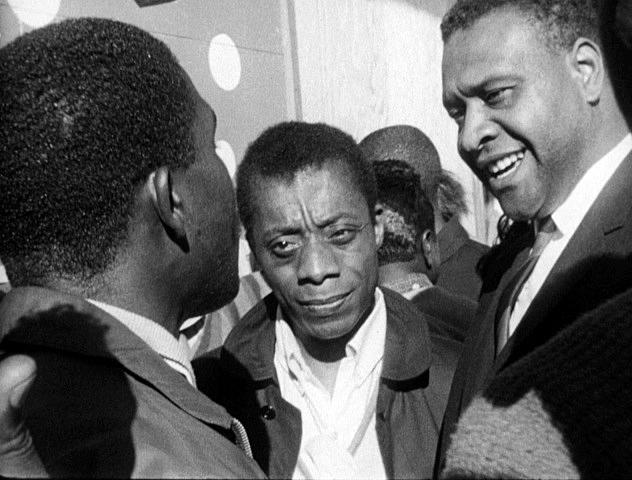

James Baldwin with Orville B Luster in the Bay View in 1963.

Photo via KQED

Clam chowder and reminiscences finished, Williams savors a lasting honor to his mother’s legacy, the renaming of the historic Bayview Opera House, which she worked so hard to protect. But not even Ruth Williams could stop the Navy from closing the Naval Shipyard in 1974, which led to an economic and social meltdown that the Hunters Point community has yet to recover from.

Senator Robert F. Kennedy visits Hunters Point in 1967.

Photo via the San Francisco State Television Archives

Part II next week: What happens after the Shipyard closes in 1974.

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.