‘One of the worst abusers’: An Alabama case highlights the state’s physical child abuse problem

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Anna Claire Vollers, a participant in the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2018 Data Fellowship.

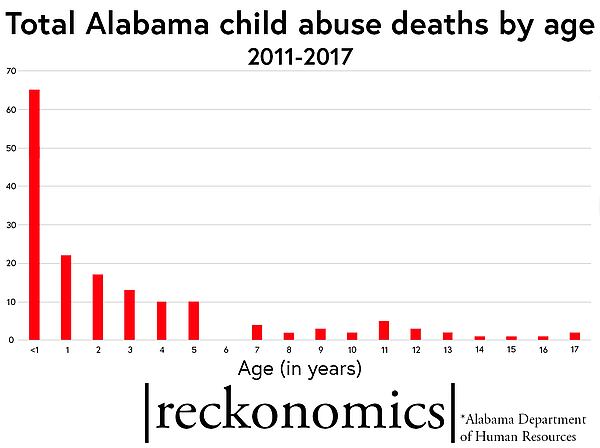

Child abuse deaths by age

Data: The Alabama Department of Human Resources

Serenity Renfroe, not quite 2, spilled her cereal.

It scattered across the floor of the little house on Rail Splitter Road where Serenity lived with her mom and her mom’s new boyfriend. They mostly kept to themselves. Rail Splitter Road cuts through a sparsely populated area near Phil Campbell in the rural northwest corner of Alabama.

Her mother’s boyfriend, Shannon Gargis, 28, had moved in with them two months before.

That Monday he was babysitting Serenity after driving her mom, Hailey Renfroe, 20, to the McDonald’s where she worked third shift.

The spilled cereal made Gargis mad.

He’d gotten mad at Serenity a lot that week, investigators would later learn.

Sometime that night, March 21, the blonde toddler from Franklin County became the third child to die from abuse in Alabama in 2016.

It was, the district attorney later told AL.com, “one of the worst beating cases I’ve ever seen. Still is.”

While child abuse and neglect take different forms, more than half of Alabama’s child abuse and neglect victims – 52 percent – experience physical abuse. That’s nearly three times the national average, according to the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services’ 2017 Child Maltreatment report.

That puts Alabama in the top five states in the nation for physical child abuse victims.

And while Alabama’s rate of death from child abuse or neglect is only slightly higher than the national average, most of those deaths aren’t from things like unsafe sleep conditions or drug exposure.

They’re from physical abuse.

What we learned

The details in Serenity’s case are disturbing.

But the elements involved in her death – catastrophic physical abuse, a young victim, a male perpetrator – repeat themselves with slight variations in dozens of other child abuse death cases across the state.

Here’s how we know that:

In October 2018, AL.com requested information on every child abuse or neglect death between 2011-2017 from the Alabama Department of Human Resources, the agency tasked with identifying such cases.

Five months later, DHR provided information on 154 deaths. AL.comfound 10 more deaths that fell within the 2011-2017 timeframe and appeared to clearly be the result of child abuse, from news reports and publicly-available court documents.

Federal and state laws keep some details out of public view. And Alabama DHR is not required to keep track of what happens after a child abuse fatality - whether an abuser is convicted, for example.

AL.com used news reports, interviews and court documents to piece together additional information for as many of the cases as possible. Reporters from the Boston Globe’s Spotlight team provided AL.com with autopsy reports on some of the victims, gathered through their reporting on the issue of child abuse fatalities nationwide.

And while some pieces of information remain missing, the data overall offers a glimpse into the lives of Alabama’s youngest victims, like Serenity, and their families.

The youngest victims

Babies and toddlers are the most vulnerable to abuse.

Like Serenity, most of the Alabama children who officially died from abuse or neglect in Alabama from 2011-2017 were under 3 years old. Nationally, children under 3 account for about 72 percent of child fatalities, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

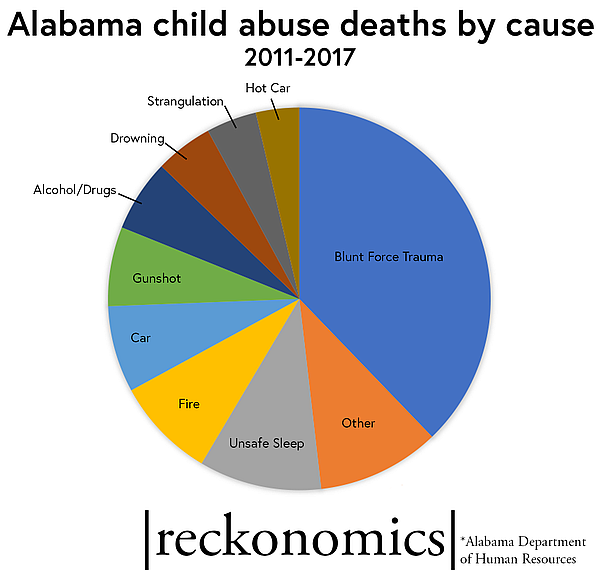

The most common cause of child abuse death in Alabama was blunt force trauma, which accounted for nearly 40 percent of the child abuse deaths; no other cause came even close.

Those are situations like Serenity’s, where someone beats or shakes or throws a child so hard that the injuries are fatal.

The perpetrators in these cases are nearly always men; in at least two-thirds of the cases the killer was the father, another male relative or the mother’s boyfriend.

“The majority of the kid deaths I have dealt with are blunt force trauma,” said Tim Douthit, an assistant district attorney in Madison County who often prosecutes child abuse cases. “Somebody will come in, (saying) ‘Oh, the baby fell down the stairs.’ Well, the baby didn’t fall down the stairs, it got beat to death.”

Most child abuse deaths didn’t appear to be intentional, based on news reports and court documents. Often, the killer simply lost control.

“Most of those men are not intending to kill a child,” said Douthit. “Things are getting out of hand, the baby won’t stop crying and they keep hitting it, and because it’s a baby, it winds up dead.

“If there’s a standard child abuse death, that’s the standard child abuse death.”

Child abuse deaths in Alabama by cause of death, 2011-2017, from data supplied by the Alabama Department of Human Resources.

Corporal punishment

One possible explanation for Alabama’s high rate of physical abuse may be the types of discipline that are considered acceptable in this state.

“We have a higher preponderance of physical abuse than the national average, and I think part of that is because corporal punishment is more acceptable in the Southern states,” said Paula Wolfteich, intervention and clinical director at the National Children’s Advocacy Center in Huntsville, Ala. The center provides services and programs for child abuse victims and for professionals who work with them.

“We do get quite a bit of that, and it’s hard to prosecute.”

Shannon Gargis admitted to investigators that he physically disciplined Serenity more severely than his own children, and he said he’d been too rough with her in the days leading up to her death, according to court documents filed by the DA’s office.

He also admitted to hitting her in the face and spanking her “harder than appropriate.”

Troubled history

The signs were there.

In February 2016, a month before her death, Serenity was at the local Piggly Wiggly with her mother and Gargis when two women noticed bruises or marks on Serenity’s head, according to testimony given by the women to investigators and filed in publicly available court documents.

The women said Gargis was talking harshly to Serenity and her mother. They said when they approached Gargis and Renfroe and asked about what looked like a head injury on Serenity, Gargis looked startled and said Serenity had bumped an end table while running around at home.

In the week before Serenity was killed, Gargis claimed she accidentally injured herself at least three times while he was babysitting her, according to testimony he gave investigators, said Franklin County District Attorney Joey Rushing.

“Every time he was alone with that child, the child ended up bruised or hurt or injured,” said Rushing.

Gargis claimed Serenity had a seizure a week before her death and that he tripped and fell on top of her, injuring her, according to Rushing. A few nights later, Gargis said, she climbed up on a pile of bicycles and fell, hitting her head.

The night before her death, he said she crammed too many chicken nuggets into her mouth at dinner and he had to dig them out, leaving bruising on her cheeks and forehead.

Her mother saw the bruises, she later told investigators, but Gargis continued to babysit Serenity. Renfroe declined to comment for this story.

It’s unclear if anyone called child protective services to report possible abuse. No prior services were listed in the data sent by Alabama DHR, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the family never had contact with child protective services. Federal law directs agencies like DHR to only release information about prior involvement with a family if the original complaint is deemed “pertinent to the fatality.”

Prosecuting abusers

Child abuse cases, and blunt force trauma cases in particular, can be difficult to prosecute.

“It’s the kind of thing that invariably happens at home somewhere and nobody sees the actual beating,” said Douthit. “We just wind up with a kid in the emergency room or on an autopsy table.”

Alabama DHR does not track criminal outcomes for the child abuse and neglect deaths they encounter, so AL.com used news reports and court documents to piece together narratives for as many of the deaths as possible. Information remains incomplete for some cases.

In the 81 cases for which criminal outcomes could be found, more than half resulted in plea agreements. Often the accused killers would be charged with capital murder and end up pleading to lesser charges, like manslaughter or aggravated child abuse.

“If they plead out,” Douthit explained, “they usually end up pleading to manslaughter or reckless murder.”

In child abuse cases, it can be difficult to prove the abuser intended to kill the child, which is required for a capital murder conviction. “But if I can prove he did it, beat a kid to death, I don’t care what your reason is, that’s manslaughter,” he said.

Gargis was charged with capital murder and aggravated child abuse. In November 2018, after a three-week trial and two days of deliberation, the jury convicted him of manslaughter and of aggravated child abuse. He received the maximum sentence, a total of 40 years in prison.

“I do think,” said Rushing, “(Gargis) is one of the worst abusers we’ve ever dealt with.”

Renfroe pleaded guilty to hindering the prosecution, for lying to police about where she found Serenity’s body. Her aggravated child abuse charge was dropped as part of her plea deal and for lack of evidence.

In the end

What happened the night Serenity spilled her cereal is a story Gargis changed multiple times in the wake of her death.

The version Gargis finally settled on, the one he told at trial, was that he picked Serenity up by the neck and threw her against the love seat in the living room.

She tried to sit up but couldn’t, he later told investigators, and then she was still.

Gargis went to bed.

Hailey Renfroe arrived home around 2:30 a.m. to find her daughter laying at the foot of the bed where Gargis slept. The little girl looked bruised, and wasn’t breathing, according to court documents.

The couple called 911 about 30 minutes later. Paramedics found Serenity lying on the love seat. She was pronounced dead.

Gargis may be one of the worst abusers, as Rushing said, but he’s not alone. In the data compiled by AL.com, child abuse victims and their perpetrators spanned the racial and economic spectrum.

“This is one of the few things that you see across the board: rich, poor, black, white, urban, rural,” said Douthit.

“There are some crimes that clearly fall into one group or another, or by socioeconomic class, but child abuse is not one of them.”

[This story was originally published by al.com.]