One year later, U.S. nurses feel unprepared for the 'next Ebola'

Anna Almendrala’s reporting on Ebola’s impact on the U.S. was undertaken as a 2015 California Health Journalism Fellow at the University of Southern California's Annenberg School of Journalism. This is the third in a three-part series about the different ways the global Ebola outbreak has changed the United States.

Other stories in the series include:

If Ebola hits again, this state is doing everything right (Part 1)

How U.S. hospitals are defending themselves against the next big outbreak (Part 2)

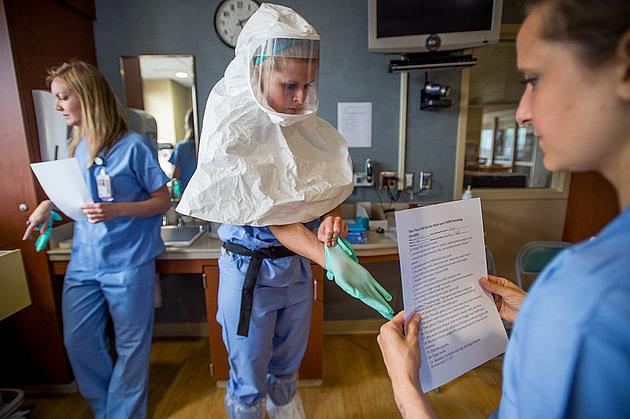

Cassandra Clark puts on protective gear during a weekly drill for Ebola preparedness at the Special Diseases Containment Unit at the University of Minnesota on Thursday, June 25, 2015 in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

MINNEAPOLIS — On a recent morning in June, Cassandra Clark spent 45 minutes in what is known as an Ebola “space suit” — an enclosed plastic hood, smock, plastic apron, and two layers of gloves and shoe coverings. The gear was part of the 57th contagious virus drill that the University of Minnesota Medical Center had executed since last November. It was a hot summer day and Clark was sweating, but she was also eager to show off her training.

Clark, an ICU nurse, is part of an elite, 19-member Ebola care unit at UMMC. Her group has been focused on treatment training since shortly after 2014’s Ebola outbreak arrived in the U.S. with Thomas Eric Duncan, a Liberian man who died of the disease in a Dallas hospital last October. Quickly selected to serve as one of 55 special assessment centers nationwide, UMCC was charged with safely receiving patients suspected to have Ebola. Six months later, the team's mission grew even more serious: the federal government designated the hospital one of just ten planned regional treatment centers for Ebola and other highly infectious new threats, such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome virus, anthrax and other emerging pathogens.

“We have all different kinds of patients and we’re very lucky to get very interesting cases,” said Clark as she stood in UMMC's gleaming, newly-retrofitted Special Diseases Containment Unit. “And this is just another part of that, [of] being part of the bigger picture of health care."

The Ebola outbreak in West Africa killed over 11,000 people, a whopping 513 of whom were health care workers -- hence the disease’s nickname, "nurse killer." In fact, the only people to actually contract the disease in the U.S. were two of Duncan's nurses in Dallas, Nina Pham and Amber Vinson. A year after the crisis came to the U.S., many public health experts, hospital administrators and federal agents agree that American nurses are safer than ever from infectious disease, thanks to a national conversation about nurse safety as well as a heightened awareness of infectious disease protocols.

But Clark’s training experience isn’t typical among nurses, and some healthcare workers on the ground aren’t so sure that they're any safer from infectious disease than they were last year. Instead, they see a slow-moving federal bureaucracy that has lavished funds and training on a small group of Ebola treatment facilities like UMMC without improving safety for the vast majority of nurses.

After the 2014 outbreak struck, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services created a two-tier system, granting funds to select hospitals to ensure they can either safely temporarily care for possible Ebola patients or treat them long-term, the latter designation so far given to just nine of a planned 10 hospitals. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration is currently considering instituting new standards to hold hospitals accountable for infectious disease protocols, and California’s nurses unions are lobbying to make sure the state’s Ebola guidelines become the standard for the rest of the nation. And if agencies don’t manage to protect nurses with new laws, the courts might accomplish it: Pham is suing her hospital’s parent company for negligence, potentially setting a legal precedent for all other nurses who want to hold their hospitals accountable for failure to control infections.

'It just doesn’t give me faith'

The vast majority of the 5,600 hospitals in the U.S. are not part of the HHS-designated system, and they don’t receive the funding or training that Clark and her colleagues do. Instead, information about new infectious diseases is piecemeal and unregulated, leaving everyone, but especially healthcare workers, open to the next infectious disease threat.

Kim Branciforte, a registered nurse who works at Children's Hospital Oakland.

“It just doesn’t give me faith that the next time that something happens, or the next time that Ebola breaks out, that we’re going to be preventative as opposed to responsive,” she said.

Branciforte wishes that the frenzy of preparing for the 2014 Ebola outbreak could carry over into safety and communication improvements for all nurses, not just those in specialized units like Clark's. All of last year’s fuss over Ebola was a “missed opportunity” for more education, support and training for nurses, she said.

“You have your nurses saying, 'I want more education so I can protect myself, my family and my patients,'" she said. “If there are [administrators] at my hospital that want to be more aggressive with this, I don’t know who they are and I don’t know what efforts they’re making.”

While Children’s Hospital Oakland spokeswoman Melinda Krigel confirmed that staff did post a sign in the emergency room about MERS, she said the emergency department also directly disseminated MERS information straight to nursing staff. Krigel also defended the hospital's alert level, emphasizing that MERS is rare in the U.S. -- the country has only ever seen two cases -- and that it is not often seen in children.

California's nurses push forward

Bonnie Castillo, a registered nurse and a director at National Nurses United, a union that represents almost 185,000 nurses nationwide, was collecting protective medical equipment to send to West Africa in the summer of 2014 when she had a startling realization: U.S. hospitals weren’t any better prepared.

“We actually procured 1,000 hazmat suits, and as we were getting ready to send them, we realized we needed to do an inventory of our hospitals in the U.S.,” said Castillo. “We realized we were not ready.”

Bonnie Castillo, director of the Registered Nurse Response Network at National Nurses United.

Quickly, the union pivoted toward protests in the U.S. to raise awareness about the dangers nurses faced. The actions included a massive “die-in” on the Las Vegas strip on September 24, 2014, as well two days of vigils, rallies and strikes across 16 states on November 11 and 12.

“Right now, the hospitals really still are left to do whatever they want to do, for the most part,” said Castillo.

In California, about 20,000 nurses participated in these actions, according to the union. As a result of the organization's efforts, the Cal/OSHA agency, generally regarded as one of the most progressive and proactive state occupational safety and health agencies in the nation, released guidance November 14 that explains how existing safety standards should be interpreted regarding Ebola. It combines California’s singular aerosol transmissible diseases standard -- it's the only state that has one -- with its bloodborne pathogens standard, determining how all hospitals must train employees at risk for Ebola exposure. The new regulations also state that nurses who go on precautionary leave after caring for an Ebola patient must be fully restored to their normal position and pay after the disease’s 21-day incubation period. These protections are not standard in the rest of the country.

Crucially, Cal/OSHA’s guidance states that all safety trainings must be conducted in-person rather than online. The new Cal/OSHA regulations would have saved Pham and Vinson from contracting Ebola last year, said agency spokeswoman Erika Monterroza.

“Training that uses only printed materials or computer-based learning, without an opportunity for interaction between trainer and trainees, or without an opportunity for hands-on practice in donning, using and doffing of personal protective equipment, would not satisfy Cal/OSHA requirements for training,” the guidance states.

Because the document is based on existing Cal/OSHA regulations, hospitals who don’t comply with these Ebola guidelines in California can be cited or fined.

Taking the movement nationwide

Progress on the federal level has been more complicated, though an initial push was swift. Despite nursing unions' reservations about the two-tiered hospital system, HHS was able to quickly set up the basic framework. In addition to creating the regional assessment and treatment tiers, the CDC updated their guidelines for personal protective equipment at “frontline facilities,” or hospitals that are not specifically trained to handle an Ebola patient but have an emergency department. For these places, the CDC recommends stocking 12 to 24 hours' worth of a complete set of protective equipment against Ebola, which is about enough time for the hospital to begin transferring a patient to an official assessment or treatment facility.

This was all accomplished with incredible and unprecedented speed, considering the sprawling and disconnected nature of the U.S. health care system. Experts like Pamela Cipriano, president of the American Nurses Association, praised the two-tiered system as well as the HHS’ rapid response to the Ebola threat.

“Like many other things in healthcare, I think once we get a wakeup call, if we realize we have an inadequate process, we learn pretty quickly,” said Cipriano, whose organization represents 3.4 million registered nurses. “What I know and what I see is that nurses and health care providers are in a much better position now, not just for Ebola but for any kind of infectious disease.”

But when it comes to changing laws and regulations to protect nurses across the country -- or even making sure that hospitals are meeting the CDC’s minimum standard of health care protection -- things get bogged down. The CDC doesn't have the power to alter rules or even enforce existing protections in hospitals. Instead, that responsibility falls to a combination of state departments of health, each charged with regulating the hospitals in their state, and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, a byzantine federal agency that regulates everything from construction workers’ hard hats to the use of formaldehyde in hair salons.

On a federal level, OSHA is considering the implementation of an infectious disease standard of protection for health care workers. It would mandate that employers establish a comprehensive infection control program, as well as subject them to citations and fines if they fail to provide training or equipment.

The agency is currently scheduled to meet in November with smaller institutions that would be affected by this new rule, to assess its possible impact on their facilities. But according to OSHA spokeswoman Laura McGinnis, it won’t be until December 2016 that OSHA will even publish the proposed rule in the Federal Register, an unofficial daily publication in which the government publishes proposed and final federal agency regulations. It could take years before that proposal becomes an official regulation.

Until then, Cipriano acknowledged, there’s no reliable way to tell which hospitals are complying with CDC’s minimum guidance for frontline facilities and which aren’t.

“I can’t really tell you whether every organization has done that,” said Cipriano. “That would be difficult to know.”

The courts get involved

Of course, there's another tried and true way to create de facto safety regulations for employees in America: lawsuits.

McGinnis confirmed that though hospitals can be cited or fined for generally failing to stock equipment or train workers, OSHA will not punish Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas -- where Pham and Vinson contracted Ebola -- because it faced the first cases of hospital-based Ebola transmission in the country. Pham, however, doesn’t think her hospital should escape censure, and she wants to make sure that no American nurse goes through what she did.

In this Oct. 24, 2014 file photo, nurse Nina Pham poses for a photo at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. (AP Photo/Pablo Martinez Monsivais)

Texas Health Resources is fighting Pham's suit, though the company released an independent report Tuesday detailing the hospital's many failures, including lack of communication and a misconfigured electronic health record system. Last October, THR's chief clinical officer and senior executive vice president, Dr. Daniel Varga, admitted in a Congressional hearing that nurses did not go through Ebola care training before caring for Duncan, though the hospital had claimed they were prepared. Nurse Briana Aguirre, who was assigned to care for Pham once she contracted Ebola, also came forward with allegations of failings on the part of the hospital, including that their infectious disease department didn’t have protocols for how to handle an Ebola patient or samples.

Pham says in court documents that she doubts that she can ever return to caring for patients, in part because of emotional trauma she still faces, but also because of the fear and stigma that still surrounds her. She is also concerned about the long-term health consequences of beating Ebola and receiving experimental treatments; for instance, she says she is worried about the impact that the ordeal has had on her future ability to naturally conceive and bear children. Seeking unspecified damages, she states in her suit that she wants to “send a message” to other hospital corporations that health care workers should come first.

"Nurses should not have to take on a death sentence in order to care for people,” said Charla Aldous, Pham’s attorney, later adding in a statement that "A win for Nina would be a win for nurses everywhere. It would send a message to major corporate healthcare systems that they have to invest in and protect frontline nurses instead of putting their profits and brands above the people who work there."

In suing THR, Aldous hopes to uncover information that will help other nurses around the world advocate for their own protection. The lawsuit is currently in the discovery phase, and Aldous has no estimate for when the suit will head to trial.

“It’s probably going to be a long fight, but we will fight to the end,” said Aldous, “so that what happened to Nina and Amber did not happen in vain.”

The fight against Ebola isn't over, either. While Liberia has been cleared of the disease, Sierra Leone confirmed there was a new Ebola death on Aug. 29, 2015 -- one week after the country was declared Ebola-free -- and Guinea is still following 728 people who may have been exposed to the disease.

This means people can still transmit the deadly virus to the U.S., and indeed, during one week in mid-August, New York City's public Bellevue Hospital Center evaluated four suspected Ebola patients. Connie Ulrich, a registered nurse and bioethics professor at the University of Pennsylvania's schools of nursing and medicine, points out that diminishing Ebola cases around the world is no reason to lower one’s guard about any emerging infectious disease.

"Although we have not had any new cases in the U.S. and it remains at a low simmer in the developing world, this does not give us cause to be negligent at any level,” Ulrich concluded. “'Out of sight, out of mind' is not a good policy.”

[This story was orginally published by The Huffington Post.]