Part 3: Filling the gap

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Marina Riker, a participant in the 2020 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Birth in the time of coronavirus

She already had a high-risk pregnancy. Then, COVID-19 struck.

Part 1: Birth on demand

Part 2: More than ‘a little snip’

Texas lawmakers aim to make maternal health a priority this year

Our women are dying': Texas lawmakers urged to extend Medicaid to a year after birth for new mothers

Certified nurse midwife Annie Leone talks with her patient, Melissa Woodfin. Prenatal care visits with the midwives at Holy Family can last up to 45 minutes — much longer than a typical doctor’s appointment.

Jerry Lara /Staff Photographer

This is the last of a three-part series:

The morning Cristina Cantu went into labor at her home in Laredo, she and her husband piled into their Nissan Altima with their firstborn son and headed to San Antonio, 160 miles away.

Their destination was the San Antonio Birth Center, a free-standing facility run by licensed midwives. Cantu didn’t want to give birth in the hospitals in her hometown because of their high rates of C-sections and episiotomies.

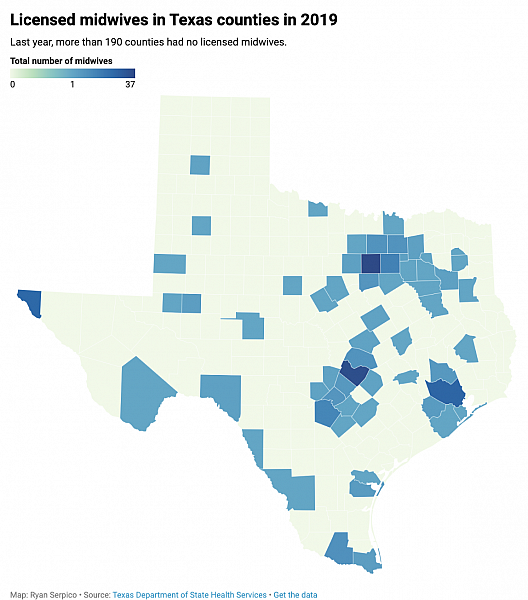

She wanted her baby delivered by a midwife, someone who would avoid medical intervention unless absolutely necessary. She couldn’t find one in Laredo. That’s a problem for pregnant women across Texas, where 194 of the state’s 254 counties last year had no licensed midwives and 31 others had only one.

For her first birth in late 2009, Cantu hired Alisa Voss Godfrey, a San Antonio midwife, to drive 320 miles round-trip to Laredo. But by the time Cantu was expecting her second child in 2014, Godfrey had started the San Antonio Birth Center and was too busy to make the journey.

Undaunted, Cantu drove five hours round-trip to San Antonio for prenatal visits: once a month in the beginning of the pregnancy and then every week during the final month.

Maria Peña cleans one of three birth houses at the Holy Family Birth Center. The center has cared for mothers and babies in Weslaco for nearly 40 years. Jerry Lara /Staff Photographer

When she went into labor, Cantu and her husband headed back to San Antonio, whizzing past ranches and brush on Interstate 35 as their 4-year-old son slept in the back seat. But Cantu’s labor progressed faster than expected, and they were still a few blocks from the birth center when the baby’s head began to crown.

Her husband pulled over and got the midwife on the phone. She gave him directions; and after a few moments, he delivered their healthy baby girl in the front passenger seat of the car.

“The reason that we weren’t freaking out in the car is because it’s a normal process,” Cantu said. “For us, this is birth — birth is painful, birth is uncomfortable, birth is messy. It’s going to be OK.”

Cantu’s daughter is now 6 years old, and the options for pregnant women in Laredo today are as limited as on the day she gave birth. Women there must rely on the city’s strained hospital systems and on severely overburdened OB-GYNs.

Massive swaths of Texas are considered maternity care deserts, where women must drive more than an hour for health care. More than 150 counties — home to more than 2 million Texans — have no OB-GYN, a situation largely driven by rural hospital closures and physician shortages.

Some physicians and midwives say increasing access to midwifery care could help fill those gaps and improve care for pregnant women.

“What we’ve forgotten along the way is obstetricians have a skill set, and we’re surgeons — we do complex medicine,” said Dr. Neel Shah, an assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School. “(Midwives) bring a whole skill set and art around supporting people in labor that’s really important and is one of the few evidence-based things that’s been shown to reduce C-section rates.”

A better way?

In some European countries, it’s common for midwives to care for women with low-risk pregnancies. That allows doctors to focus on mothers with high-risk pregnancies and serious complications.

In those countries, women are less likely to die during pregnancy or childbirth than women in the U.S.

“That is probably the model that provides the best care,” said Dr. Tony Ogburn, chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley.

Before moving to Texas in 2015, Ogburn practiced in New Mexico, where midwives oversee at least 1 in every 4 births, according to federal data. In Texas, midwives manage fewer than 1 in 20 births.

Certified nurse midwife Annie Leone checks the heartbeat of Melissa Woodfin’s baby. Leone works at Holy Family Services, the nonprofit that runs the Holy Family Birth Center — the only free-standing birth center operated by certified nurse-midwives in the Rio Grande Valley. (Jerry Lara /Staff Photographer | Express-News)

At the teaching hospital where Ogburn worked in New Mexico, certified nurse midwives oversaw 35 percent of births, allowing obstetricians to concentrate on high-risk patients. Women had the option to choose between receiving care from a midwife or a physician.

“We had a completely integrated, collaborative practice: There was a midwife on call in the hospital, there was an OB-GYN on call in the hospital,” he said. “We took care of high-risk patients, and when the low-risk midwifery patient became high-risk — there were infections, she started bleeding — (the midwife) would come to us and say, ‘Can you look at this and see what you recommend to do?’”

Ogburn said integrating midwives into health systems can lead to fewer interventions, lower costs and improved experiences for mothers.

Yet compared with states where midwifery care is well-established, Texas has more limitations on the scope of midwives’ practice. It limits their ability to use lifesaving medication and their autonomy to practice in hospitals.

Many health insurance plans won’t pay for women to see licensed midwives outside hospitals, even if births take place in licensed birth centers. It means that most women must pay cash for midwifery care, limiting access to those who can afford it.

‘There’s this stigma’

“The insurance companies make it extremely difficult to get credentials — to credential your birth center, to credential your midwives. It is not an easy process whatsoever,” said Sandra de la Cruz-Yarrison, executive director of Holy Family Services in Weslaco. “That’s why a lot of midwives are not able to set up a practice and why those that do don’t often make it.”

Located in the heart of the Rio Grande Valley, Holy Family Services was created in 1983 with donations from the Diocese of Brownsville to serve mothers and babies who might otherwise lack access to health care. It’s the oldest free-standing birth center in Texas, de la Cruz-Yarrison said, and to this day is one of the only ones in the state to operate as a nonprofit.

It’s staffed solely by certified nurse-midwives: advanced-practice registered nurses trained to provide care throughout the course of a woman’s life. The services they offer range from birth control counseling for teens to Pap smears to screenings for postmenopausal women. Besides delivering babies, they provide checkups for newborns up to 1 month old.

Holy Family is one of the only centers across South Texas that, on top of private insurance and cash, accepts government insurance, including Medicaid. About half its patients qualify for such programs.

Even though women with lower incomes are more likely to have poor access to health care, which can complicate pregnancies, the center’s birth outcomes are significantly better than Texas’ as a whole. Over the last four years, Holy Family’s pre-term birth rate has been half the Texas average.

The percentage of its patients who undergo C-sections — a procedure for which they’re transferred to nearby hospitals — has ranged from 3 to 9 percent. The statewide rate of C-sections is 35 percent.

Yet de la Cruz-Yarrison said there’s a persistent lack of understanding across South Texas — and particularly along the border — about how midwives are trained and how they practice.

“There’s this stigma along the entire border area about midwives, and people thinking that they won’t be able to get an actual birth certificate,” said de la Cruz-Yarrison.

Today, only seven out of 32 counties along the 1,254-mile U.S.-Mexico border in Texas have licensed midwives. The majority are in El Paso or the lower Rio Grande Valley near McAllen.

Maria Peña cleans one of three birth houses at the Holy Family Birth Center. It’s one of the only free-standing birth centers in Texas that operates as a nonprofit to serve mothers and babies who might otherwise face barriers to health care. (Jerry Lara /Staff Photographer | Express-News)

That’s what Cantu ran into when she became pregnant. Decades earlier, a Laredo midwife birthed her father. But that was a generation before the federal government cracked down on midwives along the border for selling U.S. birth certificates to parents of babies born in Mexico.

By the time she was pregnant in 2009, the city had only one licensed midwife, who still runs a small birth center geared to women coming from Mexico to give birth in the U.S.

Cantu briefly considered giving birth in a hospital and called Laredo obstetricians to learn about their typical deliveries. She spoke with mothers who’d recently given birth, too. She learned that induced labor, anesthesia and cesareans were the norm in Laredo hospitals. So were episiotomies, a procedure in which a surgical incision is made at the opening of the vagina to widen the birth canal.

“That’s what I wanted to avoid: I didn’t want to surrender the control of what could be a natural experience to someone else’s convenience,” she said. “There is a big gaping hole — like what happened here? It’s sort of a joke in the community that the care is 10 years behind everywhere else.”

This story was produced with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s Data Fellowship. Cheryl Phillips, Stanford University's Hearst Professional in Residence and director of Big Local News, and Danielle Fox of the Center for Health Journalism provided mentorship.

[This story was originally published by San Antonio Express-News.]