Part 4: Scarred and abandoned once again, Ashley’s rage takes control

This is Part 4 of a five-part series was produced as a project for the 2017 National Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Ashley’s foster home seemed perfect. It held a dark secret.

Becoming a pawn in the culture war, Ashley hides her abuse from the world

Ashley reveals her abuse and loses everyone she loves

Ashley finds the freedom to fall — and to discover her destiny

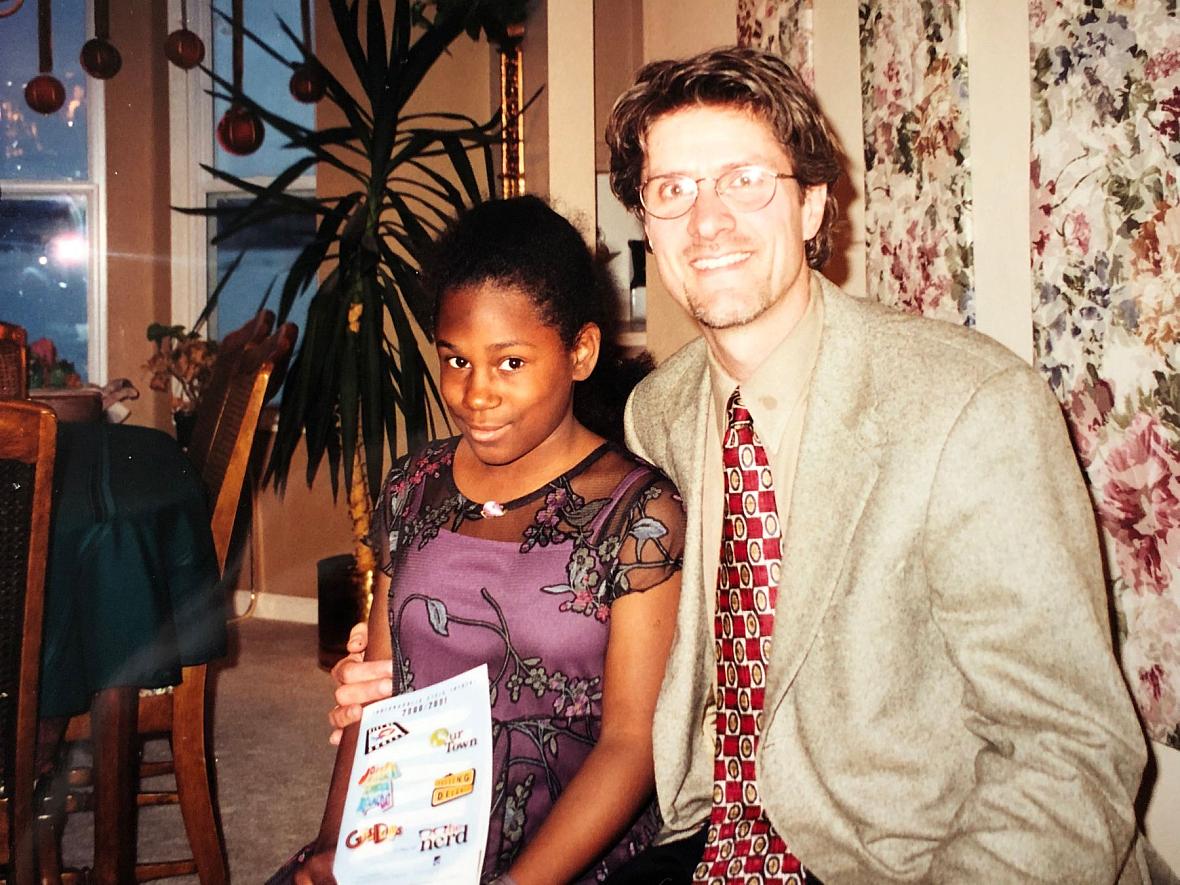

Craig Peterson with his daughter, Ashley.

PROVIDED

For years, Sandy had characterized Craig as weird. Kind of girlie. Maybe even a pervert. Now she was making Ashley go live with him.

Head down, Ashley shuffled past Craig and silently climbed into his red Jeep Cherokee Sport. Craig quickly loaded his Jeep with Ashley’s few possessions, which were stuffed in a couple of boxes and plastic bags.

Sandy had sold all of Ashley’s favorite Barbie toys — the movie theater, the grocery store, the house, the RV — and the dollhouse with little people and furniture. Sandy refused to let Ashley keep her childhood photo albums. That hurt.

It was a few days after Thanksgiving in 2000.

Craig realized Ashley was very withdrawn and there was no need to be having a celebration. It would just make things more awkward.

Part of Ashley was numb, disassociated from the confusion, hurt and anxiety of being given away to a stranger. “It was neither here nor there,” Ashley recalled, “because it wasn't the first place that I was dropped off.”

Ashley had been taken from her biological mother, paraded around for political purposes, molested by her adoptive father, and tossed from home to home. But this was a new kind of betrayal.

It wasn't just that Sandy no longer wanted Ashley. She was now willing to turn her over to a man she had all but characterized as the devil.

In that moment, another emotion flickered to life in Ashley: anger.

Things seemed to be going well

Craig did everything he could think of to ease Ashley’s transition into his home.

He hired an attorney to track down Sandy and persuade her to sign a document relinquishing her parental rights. He initiated adoption proceedings. He enrolled Ashley in Eastbrook Elementary School as Ashley Peterson — her third last name in as many years — to give her a sense of belonging and protect her from the notoriety of the last name she shared with her abuser, Earl “Butch” Kimmerling. And Craig visited the school nearly every day to brainstorm with her teacher about how to help Ashley succeed.

He didn’t want to say or do the wrong thing. He wanted Ashley to feel valued. He wanted her placement with him to work.

From Craig’s perspective, Ashley was settling in. She earned the most improved student award at the end of fifth grade and was selected to sing the national anthem during a school assembly. At home, she enjoyed playing with blocks and playing grocery store, school and restaurant with her brothers in the basement.

“I would open the door, and I would just look in,” Craig recalled. “And it was just like you would have thought these children had been together their whole lives.”

The situation seemed to be going so well that Craig adopted two more children. Alex and Travis moved in at the end of 2001.

But with six kids now in the household, things weren’t going as well as Craig thought. Not for Ashley.

‘On speed dial with the school’

Ashley could not turn off the feeling that had gripped her most of her life. She felt like an “extra.”

She believed Craig didn’t really want her. He wanted her brothers. Now she was living in his home, and he expected her to love and be the big sister to these boys she barely knew.

“I kind of just got dumped here, and then you expect me just to fit in like I’m some type of piece of clothing or something,” she remembered thinking.

Ashley had lived through at least half a dozen of what experts call “adverse childhood experiences,” which include abuse, neglect and family challenges.

Such experiences create dangerous levels of stress that can disrupt children’s brain development and impair their ability to cope with negative emotions. As the number of traumatic experiences increases, so does the risk of attempted suicide, depressive disorders, high-risk sexual behaviors and negative health outcomes.

Ashley’s earliest years were spent with her biological mother, who had struggled with alcohol use, domestic violence and mental illness. Ashley was removed from that home amid allegations of child neglect. Then she was sexually abused by her foster father.

Ashley and her adoptive father Craig Peterson chat during a break in a dance class. (INDYSTAR FILE PHOTO)

Those experiences shaped how Ashley interacted with others. She said she didn’t feel the need to get attached to people. At her core, she wanted to be left alone.

She could be engaging and delightful when she wanted to interact with people, Craig said. But she also was anxious and hypervigilant, worried something bad might happen.

Ashley’s classmates didn’t know about her past. But they soon found out Ashley had a short fuse. She couldn’t let things go.

There were fights, suspensions. In middle school, Craig said it was one rough day after another.

“I felt like I was on speed dial with the school,” he recalled.

Trouble in middle school

In March 2002, during the spring semester of sixth grade at Guion Creek Middle School, Ashley slugged a girl on the school bus. Ashley, then 11, said she overheard the girl say something rude. The bus driver pulled over. He tried to break up the fight. Ashley hit him, too.

In November 2002, while serving an out-of-school suspension for another fight, Ashley stole $100 from a relative and spent the money at Kmart. When her family confronted her, Ashley became hysterical. She threatened to leave and “cut myself with a knife — a much sharper knife.”

In January 2003, Ashley was caught shoplifting lip gloss and earrings from a Meijer.

In April 2003, she punched and kicked Craig at home. In court later, she said, “My dad got mad at me for slamming the door. He wanted me to say sorry and I didn’t, so he hit me and I hit him back.”

Craig called Ashley “extremely manipulative.” He said her attitude and mood changed drastically from day to day.

In January 2004, a 16-year-old taunted Ashley about the seat she had chosen in the cafeteria. Ashley warned the teen, who was 30 weeks pregnant, to back off. Instead, the teen stuck her finger in Ashley’s face. Ashley shoved the teen. They exchanged blows until teachers broke it up.

“I just really had like a bull’s-eye on my forehead,” Ashley recalled years later. “Because it just seemed like I could not do anything right.”

The prosecutor’s office declined to file charges against her for the school bus fight. Prosecutors agreed to probation for some other cases. Ashley spent time in juvenile detention. But the challenges continued.

A sexual target

Sex also contributed to Ashley’s emotional turmoil. Even after Butch’s abuse ended, she was a target.

In May 2002, when Ashley was in sixth grade, a 14-year-old boy led her into a wooded area behind the middle school, exposed his penis and demanded oral sex. He pulled up Ashley’s blouse and fondled her breasts. He pulled up her skirt and touched her crotch. The boy threatened to “beat her until she bleeds” if she told anyone. She didn’t tell — even after a student reported seeing something and the assistant principal and Craig asked what had happened. The next day she took a knife to school and made sure everyone knew she had it.

In March 2004, Craig found 13-year-old Ashley in his bedroom with an 18- or 19-year-old man hiding under a blanket. She admitted they had had sex. Craig reported it to authorities and prohibited Ashley from being home alone again.

Four months later, while Ashley and her family were at a concert in the park, a man pulled her into a port-a-potty and raped her. Four of the guy’s friends stood guard outside.

Ashley saw some girls she knew from school and told them what happened. They called police, and she was taken to the hospital. When Craig and the boys caught up with her, the first words out of Ashley’s mouth were: “It wasn’t my fault this time.”

She was examined at the Pediatric Center of Hope. Results indicated “she had been traumatized sexually.”

No one ever was charged.

Unprepared for trauma

School officials tried to protect Ashley during those tumultuous years. They kept her out of the hallways during passing periods. In middle school, they allowed her to eat lunch with her math teacher so she didn’t have to interact with students in the cafeteria. More than once, they allowed her to finish school at home.

Their efforts would work for a time, but nothing lasted.

Craig said the transition to middle school was difficult for Ashley because she had to navigate a larger school, clashes with classmates and multiple teachers.

There was a direct correlation, he said, between a teacher’s ability to make Ashley feel safe and how well she performed in the classroom. She was a better student for teachers who made her feel valued and showed empathy for her past trauma.

Subtle things can be triggers for children with trauma backgrounds, such as a teacher asking students to draw their family trees or bring in baby pictures. Ashley and her brothers don’t have baby pictures.

Some teachers tried to shame Ashley when she misbehaved, saying she should have known better. It’s a technique that can work well on people who haven’t experienced trauma. But for Ashley, that shame eroded her trust.

And other school officials simply weren’t prepared to interact with a girl dealing with the aftermath of trauma.

In January 2003, Elwood Bredehoeft, a teacher working lunch duty, sent four girls out of the cafeteria for disciplinary reasons. He didn't immediately follow.

Ashley, who was in seventh grade, was heading to the math teacher’s classroom to eat lunch when she noticed classmates standing outside the cafeteria. She stopped to chat.

“They were in trouble, but I didn’t know that they were,” Ashley said at the time.

Bredehoeft, then 52, came into the hallway. One by one, he asked each student’s name and jotted it in his notebook.

Ashley refused to give her name. They argued. Ashley said she tried to explain that she hadn’t been with her classmates when they got in trouble, but he told her he didn’t have time to listen.

“You are going to the office,” Bredehoeft said.

Ashley moved toward the cafeteria.

Bredehoeft blocked one door with his body and gripped the handle of the other door to prevent Ashley from opening it. She tried to pry his hand off.

There was a brief tussle, during which Ashley fell backward, recovered her balance and charged Bredehoeft, punching his chest. He grabbed Ashley’s shoulders, trying to restrain her.

Police arrested Ashley for intimidation of a school official, battery on a school official and disorderly conduct.

In a statement to the court, Bredehoeft spoke dismissively, saying Ashley needed to get her behavior under control.

“It was not a hateful, vengeful attack, but rather the result of an apparent temper tantrum by a small child,” he wrote. “Luckily, she was too small to do any physical damage.”

Recently, he told IndyStar he had known Ashley had emotional challenges. Bredehoeft said he hoped all of his students, including Ashley, would grow up to be fine adults.

"I certainly wish her well," he said.

Some saw the situation as an example of what can happen when people don’t understand trauma.

In a letter to the court, Dr. Sharon Gilliland pointed out Ashley’s history and recommended male teachers, in particular, be careful not to touch the 12-year-old unless absolutely necessary, such as “going to her aid when she is in immediate and significant danger.”

“Her reactions to the touches of males are unpredictable and this is consistent with her psychosocial history of abuse,” Gilliland wrote.

For ninth grade, Craig hoped a smaller school might help Ashley feel safe. He enrolled her in Charles A. Tindley Accelerated School, a newly opened charter school on the city’s northeast side.

The school staff was informed about her past and agreed to be sensitive to Ashley’s mood and how they speak to her.

Ninth grade was a success. But in fall 2005, the beginning of 10th grade, everything fell apart. Ashley received her ISTEP scores. She passed the English portion of the test but just missed passing the math portion. School officials had emphasized the importance of the test.

When Craig picked up Ashley at school, he said she looked as though someone had died.

The 15-year-old was devastated. She felt ashamed. Unworthy. Not smart enough. Not good enough.

Everyone’s right, she thought.

‘It’s gotten me nowhere’

Ashley saw a host of mental health professionals over the years. She was in and out of St. Vincent Stress Centers. She also spent 3 1/2 months in residential placement.

By the time Ashley moved into Craig’s home, she already had been diagnosed with partial fetal alcohol syndrome. People with fetal alcohol syndrome often have a difficult time in school and have trouble getting along with others, according to the CDC.

Ashley also had been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder after the abuse she suffered in the Kimmerlings’ home. Youths with PTSD often struggle with aggression, low self-worth, self-harm and acting out sexually.

She was later diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, which can affect mood, self-image and behavior and result in impulsive actions and relationship problems.

Craig said mental health professionals also misdiagnosed Ashley with a variety of other disorders, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and reactive attachment disorder. Other diagnoses, such as major depressive disorder and conduct disorder, were actually symptoms of her trauma, he said.

Too often, Craig said, mental health professionals didn’t understand trauma. He said they treated individual symptoms rather than Ashley as a person.

“We were dealing with the same behaviors for six, seven years,” he said. “We kept trying to call it something else. But it was the same trauma-related condition from day one.”

Each new diagnosis came with new medication or a change to one of the existing ones. But the outcome was always the same. Or sometimes, Craig said, the outcome was worse.

Residential placement didn’t help, either.

“Oftentimes people think, ‘Oh, we're going to spend all this money and put an adolescent into a highly artificial setting and then apply a somewhat cookie-cutter approach and hope that they're going to be all better three or four months later without the daily support of their family,’” he said. “And it didn't work.”

Ashley said she would tell mental health professionals whatever she thought they wanted to hear. Whatever it took to get out.

She knew what her problem was: people asking too many questions. She refused to change. Why should she? No one else would change. No one would listen to her.

“I’ve learned how to use coping skills and how to express myself,” she said during one therapy session, “but it’s gotten me nowhere.”

And when she left the artificial settings Craig described, Ashley went back to the same environment she had left.

Ashley felt Craig didn’t have enough time for her. There were too many kids with complex needs in the household.

The most successful initiative was one in middle school in which the juvenile court, school and mental health professionals worked together: the Dawn Project.

At home, Ashley and Craig received family therapy. At school, teachers and school staff learned Ashley’s history and how best to work with her. And a mentor followed Ashley all day.

Ashley thrived. Her team considered her “a model child.” She met her probation conditions. She followed her father’s rules. Her grades improved. She served as a junior counselor at a church camp. She attended a fine arts camp. She wrote and illustrated a book.

But it was an expensive program.

In December 2003, after five months in the Dawn Project, the team decided Ashley no longer needed an educational mentor. Her prior criminal cases were closed, and she was released from probation.

Officials, in effect, declared success and moved on.

Ashley was in trouble again a month later.

Looking back, Ashley said a lot of the things that officials had tried could have been really good, but the timing was wrong.

“I was not ready,” Ashley said. “I showed signs of not being ready. … A person should’ve been able to see this is not going to or whatever. Because I’m supposed to be the disabled one. How do I see that? And then, you know — but then when I came around and I was ready, then what? Nothing.”

In 10th grade, Ashley wanted freedom. She loved Craig, and she knew he loved her. She turned to him for support. But she was sick of her father telling her what to do. She didn’t want him cleaning up her messes. Every time he insisted on doing something for her, it felt as if he was saying she couldn’t be trusted to do it herself, as if there was something wrong with her.

The teen started roaming. She skipped school or disappeared after it. She ignored Craig’s rules. She blew her curfew. She snuck out the window of her bedroom.

There was a tangle of mental health hospitalizations, fights, arrests and sexual encounters with older men.

Sexual contact, which had once been a repeated source of trauma, became the only way Ashley felt wanted. She told a police officer she couldn’t refuse anyone who asked for sex. She said she couldn’t help it.

At some point, Ashley started having sex for money. She can’t remember the first time she got paid for it. But in a journal entry, she called prostitution a “self-confidence boost” and “addicting high that thrills me in a dark way.”

“It shames me more than I show no shame in disclosing my hustle almost proudly,” she said, “like I was basically bred to be used up.”

Craig seeks adult guardianship

In 2008, Craig tried to figure out what to do. Ashley was nearing her 18th birthday. He could have washed his hands of her, say he tried, let her direct her own path as a legal adult.

“But that was not in my DNA just to walk away,” Craig said.

Instead, he decided to pursue adult guardianship of Ashley. It would give him legal authority to weigh in on decisions about Ashley's education and health care. Craig hired an attorney.

Ashley took the guardianship as another sign that she was unworthy.

On April 18, 2008, 90 minutes before a scheduled guardianship hearing, Ashley hitched a ride to Atlanta. Six weeks later, she called Craig seeking help. She was barely clothed, with no money and no identification, when she stepped off the Greyhound bus in Indianapolis.

In 2010, Craig said he couldn’t do it anymore. He wanted to go to sleep at night knowing Ashley was safe. He moved her into a condo about a mile from his house.

Over the next three years, Ashley and Craig continued to fight over his need to protect her and her desire for independence.

She was no longer in school. The state of Indiana, which had taken her from her mother and put her in an abuser’s home, had all but given up on her.

That’s when Craig emailed me.

Call USA TODAY reporter Marisa Kwiatkowski at (317) 444-6135. Follow her on Twitter: @IndyMarisaK.

[This article was originally published by IndyStar.]