The Republican who emptied the asylums

The story was originally published in Capitol Weekly with support from our 2024 California Health Equity Fellowship.

Photo via Lanterman House

Frank Lanterman won an assembly seat in 1950 with one goal: securing a steady water supply for his family’s land holdings and subdivisions in the Verdugo hills community of La Cañada outside Los Angeles, a task he completed in his first year in office.

In the years to come, his influence would expand far beyond his hometown and its parochial needs. He became one of the most consequential legislators of his time by leading the effort to transform how California cares for people with severe mental illness.

In the public’s collective imagination, Ronald Reagan is most often credited or blamed for emptying state mental hospitals, and subsequently failing to provide adequate care for former patients or people who in years past would have been patients. In reality, Gov. Reagan took his cue from Lanterman.

That there are tens of thousands of Californians with mental illness locked in prisons or living on the streets today cannot be blamed solely on decisions made in the 1960s.

There have been seven gubernatorial administrations since Reagan left office in 1975. Since Lanterman retired in 1978, hundreds of legislators have come and gone. But aftershocks continue from the seismic public policy shift that took place in California in 1967.

“Frank Lanterman’s big idea is even more important in 2024 than it was in 1967,” Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg said. That idea, still unrealized, was to “match resources with systems that make it easy for people to access the help they need.”

Steinberg was elected to the assembly in 1998, 20 years after Lanterman left office. The two never met. But as a state legislator and as Sacramento’s outgoing mayor, Steinberg has been one of the few elected leaders of his generation who has sought to continue Lanterman’s work by trying to fix “a fragmented and fail-first system that leaves too many people on our streets and in our jails.”

The policy pendulum clearly is swinging today. But to understand where we are it’s important to know what came before. That includes a look back at the legislator most responsible for the original decision, and the problems that became apparent in the 1970s but were allowed to fester for decades.

***

Lanterman, who died in 1981, has mostly faded from public view but for two laws that serve as twin tombstones – the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act of 1967 and the Lanterman Act of 1969. They were first-in-the-nation measures adopted with noble intentions and signed into law by Gov. Reagan, though they were hardly Reagan’s ideas.

The Lanterman Act of 1969 and successor measures focused on people with developmental disabilities such as Down Syndrome, cerebral palsy, and autism, and established that they are entitled to cradle to grave care.

State hospitals that once housed more than 10,000 people with developmental disabilities have all but closed. The Department of Developmental Services operates on a budget of $15.8 billion this year and oversees care for 360,000 individuals who live in communities and are assisted by staff at 21 nonprofit regional centers spread across California.

The other piece of Lanterman’s legacy, the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act of 1967, is at best an unfinished work. The 1967 law, which focuses on people with mental illness such as schizophrenia, was revolutionary for its time. It guarantees basic rights to people who, because of brain disease, damage, or abnormality, had been stripped of fundamental rights. Foremost among those rights, they could refuse help so long as authorities did not deem them to pose a danger to themselves or others, or to be gravely disabled.

Lanterman, who died in 1981, has mostly faded from public view but for two laws that serve as twin tombstones – the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act of 1967 and the Lanterman Act of 1969.

Lanterman knew that given a choice, most patients would opt to leave asylums. But he intended that the money saved by emptying state hospitals would pay for patients’ needs in their communities.

He achieved one goal, not the other.

The census of people with mental illness was 21,966 housed in 10 state hospitals in 1967 when lawmakers approved the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act. By the time Gov. Reagan left office in January 1975, there were three fewer state hospitals, wards in some hospitals were mothballed, more than 2,000 Department of Mental Hygiene workers were laid off, and 6,431 patients lived in the remaining institutions.

The state did infuse community mental health care centers with more money, but Lanterman and other leaders came to recognize that the sums were insufficient and were not spent on people most in need.

Complicating matters, the 1967 law omitted any obligation on the part of the state or local officials to provide care for people who otherwise would have been housed in asylums, and as is their right, nothing in the law compelled or encouraged them to seek treatment.

As state hospitals emptied, the number of inmates with diagnosed mental illness incarcerated in jails and prison increased, as did homelessness, to the consternation of Lanterman and his Democratic coauthors, Sens. Nicholas Petris of Oakland, and Alan Short of Stockton.

Frank Lanterman, Nicholas Petris, Alan Short

In 1971, a year and a half after the law took effect, state prison officials requested funding for an 84-bed psychiatric diagnostic unit at the prison outside Vacaville for inmates who “require repeated or long-term confinement in segregated units,” and another 1,200 psych beds at the prison outside San Luis Obispo.

Memos requesting the funding did not draw a connection to the emptying of state hospitals, but the one seeking the 1,200 beds said: “The California Department of Corrections is faced with a critical need of bed space for psychiatric management cases.”

That need has not subsided. As of August, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation reported that 38.2 percent of the state’s 92,000 prison inmates are diagnosed with a mental illness.

The number of inmates –35,157– roughly equals the state hospital patient census at its height in the late 1950s and, as a percentage, the number is rising. In 2019, 29.1 percent of the 124,000 inmates had such a diagnosis.

Separately, the California Department of State Hospitals reports that virtually all 5,800 patients in five state hospitals and another 3,800 people housed in other facilities under the department’s supervision have committed crimes. They’ve been adjudged to be incompetent to stand trial, not guilty by reason of insanity, or are deemed to be offenders with mental disorders or sexually violent predators.

Many more have no home. California has the ignominious distinction of leading all other states –by far – with 180,000 people living in shelters or on the streets, and 47 percent of the nation’s chronically homeless individuals who have a disability, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s most recent report on homelessness.

As his career was concluding, Lanterman saw what was happening. In his final year in office, 1978, The Philadelphia Inquirer produced a series about the state of mental health care called “The Moveable Snake Pit.” An Inquirer reporter spoke to the author of the landmark 1967 legislation.

“I have devoted my life to taking care of the mentally ill, the handicapped, the developmentally disabled,” Lanterman was quoted as saying. “And apparently it is coming to a rather sad and confused conclusion.”

***

The man who shaped California’s mental health system was a lifelong bachelor who was wont to say that he was married to the Legislature. He called himself an “ultraconservative,” though by today’s standards, he’d be what conservatives call a squish.

The youngest of two sons, whose father was an obstetrician, Lanterman was born into wealth in 1901, thanks to his paternal grandfather who came to California from Michigan for health reasons – he sought clean, dry air – and bought 5,820 acres in the Verdugo hills in 1876. That land became La Cañada Flintridge, a leafy Los Angeles suburb – with water – where the median home price hovers at $3 million.

Lanterman’s story is told by a dwindling number of former aides and legislators who worked for or with him; interviews conducted by Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley for its oral history project; and in papers stored at the Secretary of State’s archives, USC and Lanterman House, a museum that was the 8,000-square-foot home his parents built in La Cañada and where he lived until his death with his older brother, who also never married.

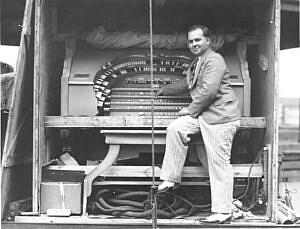

Photo from Lanterman House Archives

He studied music at the University of Southern California and as a young man played organ in silent movie houses in the Los Angeles area. With the advent of the talkies, demand for his talent ebbed and he joined the family land business, got involved in Republican politics and became president of the La Cañada chamber of commerce.

As war spread in Europe and Asia in 1941, Lanterman led an effort to ensure that deeds in La Cañada would prohibit property sales in his town to people of color, a concept that had spread throughout White well-to-do areas of California.

“Be it understood that La Cañada Valley Chamber of Commerce holds no brief for race discrimination; but we do feel strongly that we are privileged to choose our own neighbors,” he wrote in a letter quoted in a local newspaper article dated April 10, 1941, archived at Lanterman House. In later years, he did not mention that episode to fellow legislators or staffers.

Lanterman won his first run for the assembly at age 49 in 1950, at a time when the GOP dominated Southern California politics and being an anticommunist was a path to victory.

In that same election, Richard Nixon won a U.S. senate seat by defeating Congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas – a New Deal Democrat, women’s rights advocate, and Broadway and Hollywood star – describing her as “pink down to her underwear.”

In Sacramento, 400 miles from La Cañada, Lanterman resided at the Senator Hotel directly across from the Capitol and would end his days holding court at his table in the bar over a tumbler of Fundador scotch.

When Lanterman arrived in Sacramento, lobbyists doled out campaign contributions in cash, and provided whatever other fodder or pleasure legislators might want or desire.

Because he was older and came from wealth, he didn’t need “contributions.” He never faced serious opposition in his reelections, and reported raising little money, though he did disclose having raised enough to have “Uncle Frank” for Assembly buttons printed.

“I did not come here as a method of climbing the political ladder for further office,” Lanterman told the Bancroft Library interviewer. “I came here at full maturity … I was not a young, ambitious [man]. I was a mature middle-aged person, and I came for the purpose of non-political reasons.”

He was not above politics and playing to voters back in La Cañada. One of his first acts as a legislator in January 1951 was to sign onto a resolution calling on President Harry S Truman to block aid to the “Chinese Red Government.”

Later, Lanterman would fend off attacks by far right activists who likened any legislation intended to help people with severe mental illness to Soviet Union attempts to silence dissidents by placing them in gulags.

He was curmudgeonly, had his eccentricities and could be pointed in debates with his foes. He’d also regale staffers at the Senator bar with tales of playing organ in silent movie houses. Capitol denizens called him “Uncle Frank,” a term of endearment.

When the San Francisco Fox Theatre on Market Street was demolished in 1963 to make way for a nondescript high rise known as Fox Plaza, Lanterman bought the pipe organ, a Wurlitzer Fox Special, and had it shipped to his La Cañada home. There, he built a special room to house his most prized possession and would charm his visitors by performing concerts for them.

One of his closest aides, Dennis Amundson, who became Department of Developmental Services director under Gov. Pete Wilson, recalled some Lanterman’s favorite phrases: Department of Finance analysts were “pencil heads;” people in a hurry were like a “fart on a hot skillet;” and when he got annoyed with someone, he might tell them to “go piss up a rope.”

It is a tradition in the Assembly that when notable constituents die, assembly members ask that the session be adjourned in that person’s memory. Despite Lanterman’s wealth, he wore the same threadbare brown suit for years. When he finally trashed it and bought a new blazer, Assembly Speaker Jesse Unruh solemnly requested that the session be adjourned in the memory of Lanterman’s tattered brown suit, Amundson said.

He and Unruh were friends, though they disagreed on some fundamental policy matters. In 1959, Lanterman voted with Republicans against the Unruh Civil Rights Act, a landmark bill that barred businesses from discriminating against patrons on the basis of race.

In 1963, he voted against the Rumford Fair Housing Act, which sought to bar apartment owners from refusing to rent to people of color.

In other words, he was solicitous of the “right” of business owners and landlords to discriminate against people of color, but not the rights of people of color to fully participate in society. Later, in 1975, he voted with Republicans against a bill by former Assembly Speaker Willie Brown that ended criminal penalties for sodomy–laws that were used against gay people.

And yet Lanterman battled discrimination against people because of mental infirmities, and chided ACLU lobbyists by saying he championed rights of mentally ill people before civil libertarians embraced the issue.

Exactly why he dwelled on the issue of the rights of people with mental illness is lost to history. There’s no known record of a family member who spent time in an asylum. His interest in the question seems to have started with a related issue – the treatment of people with developmental disabilities, and then expanded.

He said he learned compassion from his physician-father and became acquainted with conditions in asylums from his earliest days in the Legislature.

He collected reports from the 1940s and ‘50s detailing outbreaks in state hospitals of cholera, shigella and other diseases borne of fecal-oral transmission, and he sat on a committee that held hearings on conditions in state hospitals in 1955.

Files at Lanterman House include death reports of children with developmental disabilities in the early and mid-1950s at Pacific State Hospital in Pomona, later renamed the Lanterman Developmental Center. The state closed it in 2015 and transferred the property to Cal-Poly Pomona.

Exactly why he dwelled on the issue of the rights of people with mental illness is lost to history. There’s no known record of a family member who spent time in an asylum. His interest in the question seems to have started with a related issue – the treatment of people with developmental disabilities, and then expanded.

One case involved a 6-year-old girl whose parents were not notified of her death for two days. Other reports were of a 7-year-old boy who weighed 28 pounds at the time of his death, and a 5-year-old boy who weighed 23 pounds when he died. He was especially frustrated that state hospitals housed elderly patients with dementia, saying in 1956:

“I think the Legislature has stated its opinion, the Department of Mental Hygiene has issued order after order and still there has been this inappropriate placement of some of these aged people.”

A decade later, he and his main partner, Sen. Petris, a liberal Stanford-educated attorney, cited the placement of dementia patients as one justification for changing the commitment law.

Photo courtesy: DDS

Whatever his early motivation might have been, he became the legislature’s expert on the topic, and other legislators were happy to follow his lead, said Brown, probably the most influential California legislator of the 20th Century.

“Mental health as subject matter never had a universal constituency, so it didn’t mean a whole lot for electability,” Brown, who served in the Legislature for 30 years ending in 1995, told me in a 2023 interview. “I don’t remember any significant politician making his or her vote on the budget dependent upon mental health appropriations. …

“It was not considered by anybody to be a negative, but it never developed into the same kind of political acceptance as racetracks did.”

The implication: Racetracks, like liquor, tobacco, Hollywood, the tech industry, or oil, are sources of what Brown’s most impactful predecessor, Speaker Unruh, called the mothers’ milk of politics: money.

Perhaps the explanation for his motivation was simple: He was trying to right an injustice.

Valerie Bradley was a student at Rutgers in 1966 when Unruh recruited her to work in the Assembly and assigned her to help the effort led by Lanterman to overhaul the mental health care system.

Lanterman was, she said in an interview, “a really decent man” and one “who saw the moral problems involved in taking people’s liberty away, sticking them in an institution where they got second-rate, third-rate, fourth-rate care.”

“I think Lanterman just became convinced of the righteousness of the cause, frankly, and also saw it as a bit of legacy,” Bradley said.

***

Ronald Reagan is often blamed for emptying state hospitals and not providing sufficient care once patients were freed. As governor, he had a role. But it was hardly his issue.

Lanterman and Petris had been holding hearings on the issue for years leading up to the 1967 legislation. Reagan’s predecessor, Gov. Edmund G. “Pat” Brown, presided over a dramatic reduction in the state hospital census, from a high of 37,489 in 1959 down to 26,567 at the end of his final year in office, 1966.

“Reagan is a culprit in all this, but it is a lot more complex,” Gov. Gavin Newsom once told me. “I can give a speech today and blame Ronald Reagan and half the room will start applauding and say, ‘He finally said something I agree with.’ That is so simple. … He didn’t shut down all of the state hospitals. For many reasons, they shut down.”

The 1967 legislation reflected its times. Congress had passed major civil rights legislation. Ken Kesey’s “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” was a bestseller and the Broadway adaptation starring Kirk Douglas was a hit. Activists at California campuses and on the streets were demanding greater rights. California lawmakers, including Lanterman, had voted to legalize abortions in 1967.

On May 1, 1967, Assemblyman Lanterman and Sen. Petris, aiming high, held a press conference to unveil what they and their allies said would be the “Magna Carte” for psychiatric patients.

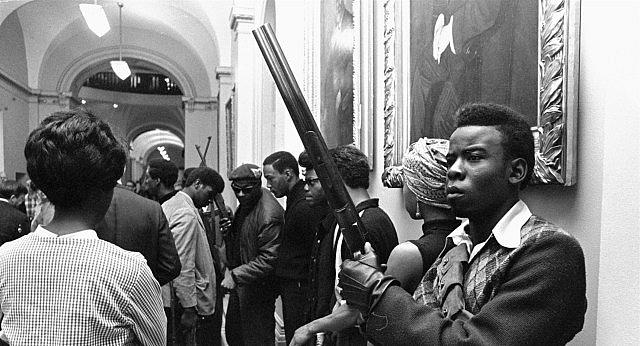

The following day, members of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense, wearing black berets, carried rifles into the Capitol and walked past sergeants at arms and into the Assembly chambers to protest pending legislation to bar the open carrying of firearms.

A Black Panther Party member brings a shotgun into the state Capitol, May 2, 1967. He was one of two dozen armed Panthers who entered the building.

(Photo: Walt Zeboski/Associated Press)

Willie Brown, a lawyer, was standing at the rear of the chambers and, while other lawmakers scattered, turned around to see one of his clients leading the entourage. Brown asked if the guns were unloaded and was told they weren’t. He gave them the lawyerly advice to leave fast before police arrived. The Panthers heeded that wise counsel. Lawmakers reacted by fast-tracking the gun control legislation – with the approval of the National Rifle Association – and Reagan signed it into law.

Although Unruh was a partisan Democrat, he entrusted Republican Lanterman to shepherd the legislation through the lower house. It was a shrewd move. Unruh wanted the legislation to become law. Reagan, who depended on Lanterman’s help to navigate the Legislature, especially in his first year, 1967, would be more likely to sign it if a Republican was its main proponent.

By a unanimous vote, the Assembly approved the Lanterman-Petris legislation. That bill, the “Magna Carta,” sought to grant rights to patients in back wards and establish a state-funded system of care for them once they return to their communities.

In the Senate, Democratic Sen. Alan Short of Stockton was less interested in granting greater rights to state hospital patients than in expanding legislation he had carried a decade earlier to help local governments pay for certain mental health services. The Senate approved his narrower bill.

Seeing Lanterman and Petris’s bill as a rival, Short used his clout to block it in the Senate. Lanterman, with Unruh’s backing, responded by bottling up Short’s bill once it reached the Assembly.

Then the brinkmanship began.

The Assembly and Senate established a conference committee made up of members of each house. In the back and forth, key aspects of the bill related to state funded care were gutted, the Assembly agreed to increase funding for county programs Short favored, and Short’s name was added to the bill as the third co-author.

Although his name is on the bill, Short remained a skeptic of the concept of deinstitutionalization, perhaps in part because his district included Stockton State Hospital, the state’s oldest asylum and a source of steady employment for his constituents.

In a note to himself, Lanterman described the upshot of the logrolling. Most of the changes were made to mollify conservatives including “pencil heads” in Reagan’s Department of Finance who were determined not to spend additional money.

Provisions requiring that counties develop plans to care for former patients were stripped out. Also omitted were provisions that might have required counties and the state to spend additional money.

“In summary – the bill makes badly needed procedural reforms but does not enact new financing or administrative changes on the state or county level,” the note, archived at the Lanterman House museum, says.

“We had to make all those amendments in the bill within a few hours and get it on the desk of both the assembly and senate chambers in order to get it out,” Art Bolton, the chief Assembly aid on the bill, said in a 2009 interview with documentarians for film, “When Medicine Got It Wrong.” (The film details a movement begun in the 1970s by a small group of parents from San Mateo County to improve care for people with severe mental illness. My parents were part of that group, as they tried to improve care for my brother.)

Gov. Reagan signs LPS 1967

Photo courtesy of USC

Reagan signed the bill on Sept. 2, 1967. In hindsight, the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act may have been the most far-reaching measure Reagan signed during his eight years as governor. Yet he held no signing ceremony and issued no press release.

“Reagan was not a big fan of mental health services,” Bolton said. “But I mean he was not really opposed to any of it. It wasn’t really much on his radar screen. It wasn’t not something he cared a lot about.”

The governor, Lanterman and all the legislators who voted in near unanimity for the measure could easily justify their action. It was the progressive thing to do. Leading experts concluded that state hospitals were little more than warehouses and people could only get well outside such institutions. California was the first to pass such a law. In the years to come, virtually every state in the union took similar action.

***

The Lanterman-Petris-Short Act took effect on July 1, 1969. Initially, experts in the field lauded Lanterman’s effort. President Nixon’s administration looked favorably upon it, commissioning a study to determine whether the bill should become the national model. Whenever it was criticized, Lanterman defended it. He also monitored how it was working and would tweak it with new legislation each year during his final decade in office.

A most basic issue remained – and remains – unresolved: housing for former patients and people who would have been sent to asylums.

One solution was to have them reside in board and care homes in residential neighborhoods. The man who in 1941 championed race-based deed restrictions faced a familiar concern. Some residents didn’t want to live next to certain types of individuals.

Thirty years later, in 1970 and 1971, he authored bills signed by Reagan seeking to ensure local zoning ordinances could not be used to exclude small group homes that housed people with developmental disabilities or mental illness from residential neighborhoods.

As Bolton saw it, "Reagan might not have even signed the legislation that we did enact if not for Lanterman’s efforts.” He also told the documentarians that the notion that Reagan emptied state hospitals was a “great oversimplification.

Lanterman wrote a letter in 1976 archived in his papers at USC thanking Gov. Jerry Brown’s health director, Jerome Lackner, for his efforts to enforce that zoning legislation:

“If the concept of community care is to ever reach its potential, we must vigorously pursue the development of a sufficient number of high quality facilities which are truly a part of the local community. Local discriminatory zoning practices have been one of the major obstacles to the achievement of that goal.”

As ever, money was an issue. Lanterman lamented that dollars saved by emptying state hospitals never followed the patient. Money that did flow to counties often was spent not on people with the most severe mental illness, but on people whose needs were more modest.

In February 1975, a month after Reagan left office and Jerry Brown was sworn in as governor, the California Auditor General found that patients released from state hospitals had no services, and often ended up back in local hospitals—at triple the cost:

“In our judgment, sufficient emphasis is not being placed on developing alternative nonhospitalization facilities at the county level. As a result, releasing state hospital patients into the community where adequate nonhospital services often are not available results in the placement of that patient in a local hospital. The net effect of this is the replacement of a $39 per day state hospital cost with a $125 per day local hospital cost.”

Lanterman long had chaired a subcommittee on mental health care. But in 1976 Assembly Speaker Leo McCarthy, aware that Lanterman was in his final term, replaced him with a young Democratic assemblywoman, Leona Egeland Rice of San Jose.

She insisted that Lanterman be vice-chair, knowing she needed help understanding the issues and personalities. He graciously passed the torch, and they became friends. She also brought fresh eyes to the issue.

“Everybody started to realize that this was a fairytale,” she said in an oral history interview with Open California. “You close the state hospital, and you normalize people by putting them in the community. But it doesn’t work. And the funds didn’t follow the people. And the trained staff didn’t follow the people.”

Lanterman had hope that in his final year in office, the problem of a lack of money might be solved. Gov. Jerry Brown, running for his second term, made a bold declaration in his January 1978 State of the State speech:

“Our hospitals have been troubled and our communities have lacked the resources to care for the growing number of mentally ill and disabled citizens. Many of you have seen this coming for a decade. One has worked longer and with more perseverance than all others.

“Frank Lanterman, this is your last year in the Legislature and may it be the year of mental health. I will support substantial increases for state hospitals and for new and expanded care in the community: to provide after-care, to provide sheltered workshops, psychiatric intervention teams, and the budding of a truly integrated human mental health system.”

Voters had other priorities. The property tax slashing Proposition 13 had qualified for the June 1978 ballot.

Howard Jarvis

Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

Lanterman took a dim view of Proposition 13, telling his oral history interviewer in April 1978 that it was a “phony bologna piece of nonsense.” He described its main author, Howard Jarvis, as “an old walrus, and an old faker, and a three-dollar bill.”

That March, Lanterman introduced legislation intended to protect funding in case the initiative passed, saying in a press release:

“Historically human services programs have been the first to be cut if there is a reduction in funds. Consequently, I introduced this legislation to require the state to provide the funding. We cannot afford to let handicapped children and adults sit on the curb waiting for services because of the enactment of the Jarvis-Gann initiative.”

The bill died in a committee on June 7, 1978, the day after nearly 65 percent of the voters approved Proposition 13. Big plans for any new initiatives would be placed on hold.

In October 1978, Lanterman, with two months left in his final term, held a press conference:

“I am deeply disappointed about the governor’s lack of credibility. Gov. Brown called this year the ‘Year of Mental Health’ in his 1978 State of the State message. At that time, he promised an $82.6 million augmentation to local mental health programs so that the dollars would follow the patients out of the state hospitals into the community. Less than $10 million actually appeared.”

A month later, Brown won reelection – and voters sent a new breed of anti-tax Republicans to Sacramento, including Lanterman’s replacement.

Egeland Rice left the legislature at the end of her third term in 1980 and visited Lanterman at his La Cañada home. They had lunch, they gossiped, and he played his Wurlitzer for her.

***

Forty years after Lanterman left office, Gavin Newsom was elected governor and deemed homelessness and the related issue of untreated mental illness to be a top-tier priority. He was not new to the issue.

As San Francisco mayor, Newsom had been an early supporter of Proposition 63, the 2004 initiative promoted by then Assemblyman Steinberg to impose a tax on high earners to pay for mental health care services.

Reagan was not a big fan of mental health services,” Bolton said. “But I mean he was not really opposed to any of it. It wasn’t really much on his radar screen. It wasn’t not something he cared a lot about.

The goal, Steinberg told voters at the time, was to establish the community mental health care system envisioned in 1967. In the years since, the voter-approved Mental Health Services Act has generated $31 billion for mental health services, though money is not the sole answer.

At Newsom’s urging, legislators have passed laws making it easier to hold and treat people who cannot care for themselves. In March, with Steinberg’s support, voters approved a Newsom-backed ballot measure that rewrote the 2004 initiative. As it was, each of the state’s 58 counties had different plans for how to spend Proposition 63 money. The state had minimal oversight.

“There was not enough focus on outcomes,” Steinberg said.

Under Proposition 1, the rewrite of the 2004 ballot measure, the state will take greater control of the money, and direct billions of dollars into housing specifically for chronically homeless people who are mentally ill, many of whom also are drug abusers.

“The state has a responsibility to insist on greater outcomes for the most vulnerable people,” Steinberg said. “You’ve got to say more money needs to be spent on housing and support for people who are vulnerable – more money needs to be spent on people who are chronically homeless. That should not be a discretionary act.”

There is more to be done, in Steinberg’s view. People with mental illness ought to be entitled to care, not unlike the right granted by the Lanterman Act of 1969 to people with developmental disabilities.

“Individuals need to say ‘yes’ if help is offered. Nobody should be living out there,” Steinberg said. “But there ought to be a legal obligation to serve them.”

The concept meets resistance for a variety of reasons. One is how to define who would qualify. Cost is an overriding issue. Providing an entitlement to mental health care, like the entitlement for care for people with developmental disabilities, would not be cheap.

As Californians can see, however, costs come in different ways. There is a cost to jailing an individual with severe mental illness There’s also a cost to having 180,000 people living on the streets or in temporary shelters, many of them suffering from brain disorders. Californians end up paying, indirectly and directly. The meter has been running since 1967.