Why African-Americans are at a greater risk of colon cancer (Part 2)

KCRW's Avishay Artsy reported this story, the second in a three-part series on African-Americans and colon cancer, as a 2015 California Health Journalism Fellow at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School of Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

The stigma of colonoscopies and African-American risk of colon cancer (Part 1)

How to reduce the disparities in colon cancer outcomes (Part 3)

Dr. Donald Henderson, a gastroenterologist and colorectal cancer specialist, at his office in Inglewood. Photo by Avishay Artsy

Each year, about 140,000 Americans are diagnosed with colon cancer, and more than 50,000 die from it. That’s bad news, but for African-Americans, it’s even worse.

“African-Americans are more likely to get colon cancer, they’re more likely to have an advanced stage of disease when they’re diagnosed with colon cancer, they’re more likely to die from colon cancer and they have shorter survival after diagnosis with colon cancer,” said Dr. Fola May, assistant professor of medicine at UCLA and a researcher at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

Yesterday, we talked about the fear and stigma of the colonoscopy test. Today, a deeper look at the research.

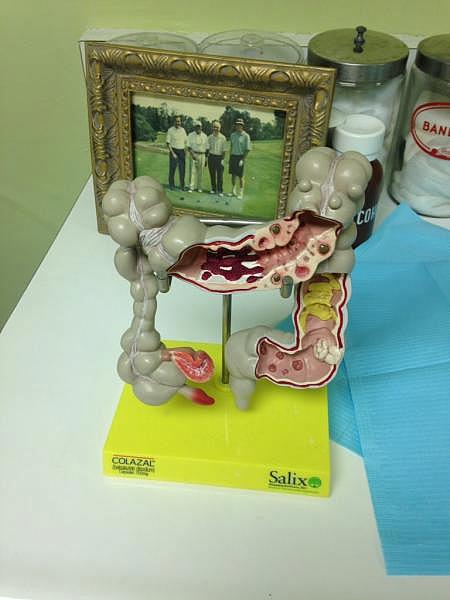

In his Inglewood office, Dr. Donald Henderson has one of those plastic medical models on his desk of a colon. Also called the large intestine, the colon has an important role. It reabsorbs water from digested food to keep the body from becoming dehydrated. It’s shaped like an upside-down horseshoe.

A medical model of a colon, in Dr. Donald Henderson’s office. Photo by Avishay Artsy

“It starts on the right hand side where the appendix is located, and where the small bowel and large bowel are joined together,” Henderson said.

The colon travels up the right side of the body, across, and back down the left side, ending with the rectum. Sometimes small bumps form, called polyps. Not all of them become cancerous, but there are a number of ways to screen for polyps and remove them. Fecal tests can detect blood or cancerous DNA. There’s a colonoscopy, in which a long, thin tube is inserted in the rectum. A tiny camera examines the right and left side of the colon. It sounds painful, but patients are asleep and don’t feel it. There’s also something called a flexible sigmoidoscopy.

“We use a short tube, the patients love it because they don’t need to be sedated and they don’t need to take a full bowel prep that you drink by mouth to have your bowels cleaned out. But it only allows us to see the left side of the colon. So we can take out polyps on the left side but that’s it. If you have one of these flat lesions or a polyp on the right side, we’re not going to get it with a flexible sigmoidoscopy,” Dr. May said.

The problem with that test is that African-Americans are more likely to develop polyps deeper in the colon, on the right side. According to the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1 in 41 black males will die from colorectal cancer, compared to 1 in 48 white males. The risk is similar for women. 1 in 44 black females will die from colorectal cancer, compared to 1 in 53 white females. But African-American men are especially likely to refuse a colonoscopy.

“Men in our focus group study and men in other studies have said, ‘I do not want any sort of procedure where I have to have any sort of instrument that’s placed into my behind.’ And that was a persistent theme throughout our focus group studies and we’ve seen it in the literature and in other people’s work as well,” Dr. May said.

Women were less concerned with that aspect of the test. Dr. May says another reason African-Americans are more likely to develop colon cancer is diet.

“So diets that are very high in fat, particularly animal fat, and very low in fiber, are associated with later in life developing colon cancer,” Dr. May said.

Other lifestyle factors among African-Americans – higher tobacco-related illness, more obesity, less physical activity, and lower intake of vitamins C and E – are also thought to be tied to colon cancer. Dr. Brennan Spiegel, director of health services research for Cedars Sinai says another factor has to do with the idea that if you’re going to die from cancer anyway, you’re better off not knowing about it. Even though the purpose of the screening is to find polyps before they become cancerous.

“This idea of cancer fatalism, we found is more common in African-Americans than in other racial and ethnic groups,” Dr. Spiegel said.

Another reason for the disparity in cancer outcomes is access to health care. African-Americans make up about 9 percent of LA County’s population, but they make up about 26 percent of the uninsured population. Another factor may be a deeply-ingrained distrust of doctors, compounded by institutional racism on the part of the traditional health care system.

“We know women with breast cancer are less likely to be screened if they’re African-American. We know that transplanted organs are less likely to be given to African-Americans,” Dr. Spiegel said.

But Spiegel and his colleagues also found that doctors are less likely to recommend African-Americans get a colonoscopy.

“We found that African-Americans were more likely to say that their doctor never recommended a colonoscopy or any kind of colon cancer screening than any other racial and ethnic groups,” Dr. Spiegel said.

Dr. Spiegel says that’s a big failure at the provider level. Americans are told to get colonoscopies starting at 50, but the American College of Gastroenterology recommends African-Americans get them starting at 45.

“And we found that when doctors do recommend screening, it increases the chances of getting screened by nearly twofold. Which makes sense,” Dr. Spiegel said.

Now, the study didn’t look at why doctors aren’t recommending the screenings. But Dr. Spiegel says it might be because African-American patients, who get checkups less often, have more pressing health problems.

“So the doctor, who’s trying to do his or her best, doesn’t even have time to get to discussions about colon cancer screening or other forms of screening when they’re handling diabetes or heart disease or high blood pressure, all these very difficult, intractable problems,” Dr. Spiegel said.

Dr. Spiegel and his colleagues published a study in August of 2014, looking at whether lack of health insurance is the culprit for higher colon cancer rates among African-Americans. So they went to a place where everyone has health care, regardless of race. The Veterans Administration.

Dr. Fola May, Assistant Professor of Medicine in UCLA’s Division of Digestive Diseases

“All veterans have access to colonoscopy. So we would think that we should see no difference in screening between African-Americans and other racial and ethnic groups in the VA, where they all have the same access,” Dr. Spiegel said.

In fact, what they found at the West Los Angeles VA is the same disparity. 42 percent of African-Americans were screened, versus 58 percent of all other groups. Again, they don’t know why that is. But it shows that fixing access to health care alone won’t solve this problem. In a study published in August of 2015, the researchers looked specifically at African-American adults in California with a family history of colon cancer – which would put them at a much higher risk of getting the cancer themselves. Of that group, only 60 percent had been screened for colon cancer.

“That’s already a big problem. But then when we drilled down into that group and looked at racial and ethnic disparities, we found that African-Americans were 71 percent less likely to get screened than white Californians. So this is an even bigger indictment,” Dr. Spiegel said.

You’d think the family of a colon cancer survivor would be more likely to get screened. But take the case of Cordell Harper. He’s 67, works for the Department of Defense and is African-American. In late 2001 he underwent surgery for colon cancer. The next summer he underwent chemotherapy sessions, once a week, for four hours each.

“Several times I got sick, lost a lot of weight, couldn’t taste my food, because the 5FU burns your taste buds, and food tastes just like metal,” Harper said.

5FU is an anti-cancer chemotherapy drug. Harper has three brothers. And even after all that he went through, they refuse to get colonoscopies.

“Fourteen years later, I don’t believe any one has done it,” Harper said.

“Wow. So, if having a brother get colon cancer doesn’t make you want to get a colonoscopy, what will?,” I asked.

“Having issues, you know, and it may be too late then. But I encourage them, I tell them you all need to get a colonoscopy because you’re all over 50 years old,” Harper said.

“So the mentality is, sort of, wait until things go wrong and then try to fix it?”

“Yes, that’s kind of the mentality.”

This story was originally broadcast by KCRW.