How OTs who work with children could do more to screen moms for depression and get them help during kids' appointments.

How OTs who work with children could do more to screen moms for depression and get them help during kids' appointments.

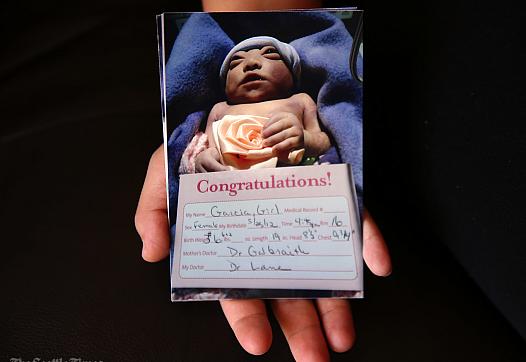

Black infants in California and across the nation are dying at higher rates than infants of other races. Communities are responding to the disparity in different ways, with some forming groups to train more doulas of color.

![[Photo by Luke Wisley via Flickr.]](/sites/default/files/styles/teaser_list_thumbnail_large/public/title_images/unnamed%20%281%29_20.jpg?itok=pj6DlVxi)

There is nothing inherent about black skin that increases risks during pregnancy — except over-exposure to the real culprit, racism, which can harm a mother’s body in real, measurable ways.

In California, Alameda County’s success in saving lives has not been replicated statewide — and an already appalling gap between white and black infant death has grown since then.

When Jessica Porten sought help for postpartum depression, she wasn't expecting the nurse to call the police to escort her to the ER. She now believes moms need far better help for their mental health needs.

Pregnant women in LA's safety net system often struggle to get adequate mental health care. The problem is made worse by the lack of psychiatrists trained to work with pregnant women.

New research finds that among very preterm babies, where they are born matters greatly. And black and Hispanic mothers are more likely to deliver at hospitals with worse outcomes.

![[Photo by Bradley Gordon via Flickr.]](/sites/default/files/styles/teaser_list_thumbnail_large/public/title_images/unnamed_146.jpg?itok=k2xAsmO8)

“Have a plan, but expect to ditch it,” a news mentor drilled into my head 25 years ago. “If you’re well prepared but open to wherever the story leads you, the journalism gods will reward you.”

A mysterious cluster of rare, fatal birth defects has devastated families in three rural counties in Washington state. JoNel Aleccia of The Seattle Times shares key lessons from how she reported her award-nominated fellowship series.

In recent months, Fresno School Board President Brooke Ashjian has launched a series of attacks on Fresno Bee reporter Mackenzie Mays over her reporting on the district's failure to provide basic sex ed to students.