What Nebraska’s big decision teaches us about the future of Medicaid expansion

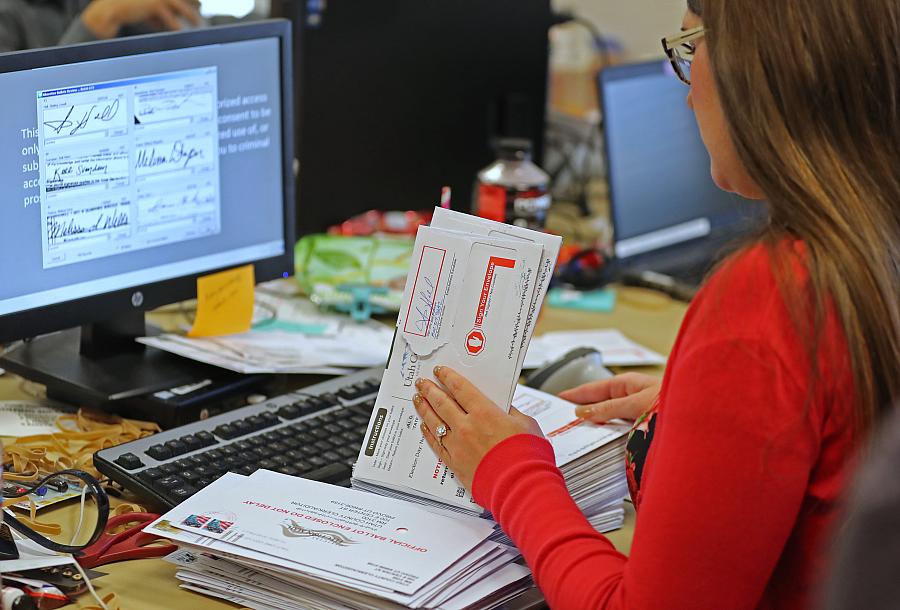

Verifying ballots in Utah, where 53 percent of voters supported expanding Medicaid.

(Photo by George Frey/Getty Images)

As a kid growing up in a liberal household in the very red state of Nebraska, my family’s thinking on matters of social justice was often out of sync with those of most Nebraskans. So I was hardly surprised when Nebraska declined to expand Medicaid in the wake of Obamacare’s passage, with the state’s one-house legislature voting six times to keep some 90,000 residents off the rolls, stranding them without health insurance.

The midterm election changed all that. With a ballot initiative Nebraskans decided by a vote of 53 percent to 47 percent to join 36 other states and Washington, D.C. to provide Medicaid coverage to some of the country’s poorest residents. Recall that the Affordable Care Act allowed states to expand their Medicaid programs to include people with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level, about $34,600 for a family of four. In 2012 the Supreme Court, however, gave states the option of expanding Medicaid and 20 states chose not to do that when the law took effect in 2014.

Nebraska’s vote was a huge victory for the many grassroots groups and others including the Nebraska Hospital Association, the Nebraska Association of Behavioral Health Organizations, the union-backed Fairness Project, and investor Warren Buffet, who supported the effort. It was a win for the cause of health insurance.

The overall takeaway from Nebraska, though, runs much deeper. It showed that the state’s residents — indeed those in several other states, too — want something done about the systemic problems plaguing American health care. The vote told us that people are willing to set aside their prejudices and stereotypes of the poor and say enough is enough. The vote told us the politics of health care have changed. It was the realization that all of us are vulnerable when illness strikes.

“Whether knocking on doors in Northeast Lincoln or in rural Nebraska, you hear the number one issue is affordable health care,” Adam Morfeld, a state senator from Lincoln, told me. Morfeld, one of the leaders of the ballot initiative effort, framed the struggle for health coverage this way: “People can barely afford it; some people don’t have it and are scared; others are suffering from medical debt; some are suffering from all three.” Campaign workers found residents who were paying more for their health coverage than their mortgage or rent, he added.

“Hard-working Nebraskans are suffering, going bankrupt and increasing all of our costs,” he continued. “People are starting to get desperate.”

Indeed the election breakthrough in Medicaid expansion, long-blocked in rural and red states, is one of the most significant recent developments in health care. People are fed up as the current system continues to escalate in cost, surprises families with unexpected medical bills, propels insurance premiums far beyond what the average family can pay, delivers too much unsafe care, and still excludes 28.5 million people from insurance.

It’s fair to assume those same concerns bothered residents in Utah who voted to expand Medicaid by a vote of 53 percent to 47 percent, and in Idaho where more than 60 percent of the residents supported Medicaid expansion. “Many of our state’s most powerful people and institutions got behind Medicaid expansion, including prominent Republicans like Gov. Otter,” says Audrey Dutton, a health journalist who has covered this story for the Idaho Statesman. “Counties that are solidly Republican also voted solidly in favor of expansion.” Dutton told me that continued punting on expansion by the state legislature finally drove people “to the polls out of frustration.”

Other hold out states may soon move into the yes column: Kansas has a new governor who supports expansion, Maine’s new governor says she will work to implement an expansion the voters had already approved but languished because the outgoing governor didn’t like it, and Democrats have gained power in North Carolina. With the end of the state’s Republican supermajority rule in the North Carolina legislature, getting more Tar Heel residents on Medicaid might be possible. Maybe even in Wisconsin there is hope for a breakthrough with the defeat of Republican Gov. Scott Walker.

The vote told us that people are willing to set aside their prejudices and stereotypes of the poor and say enough is enough. The vote told us the politics of health care have changed. It was the realization that all of us are vulnerable when illness strikes.

Back in Nebraska, the drive to gather enough signatures to place Medicaid on the ballot was fueled by a lot of community conversations, says Molly McCleery, deputy director of the health care program for Nebraska Appleseed, a nonprofit group that took on the cause of Medicaid expansion. “There was a lot of awareness of Medicaid and how important it was,” McCleery told me. “Voters know someone in the coverage gap. Most important, she added, “A lot of voters didn’t see this as a partisan issue. They saw it as something positive we could do for our communities and the state as a whole.”

The political opposition was present in Nebraska just as it was in Idaho and Utah, with the usual arguments about the cost of expanding coverage and who would pay the bill after the federal government stopped paying its 90-percent share. The state chapter of Americans for Prosperity, a Koch brothers-financed operation, and a mysterious group known as the Alliance for Taxpayers, which did not have to disclose its donors under Nebraska law, bought at least $50,000 worth of ads aimed at scaring people into voting “no,” according to the Omaha World-Herald. The World-Herald noted the group’s ad said Medicaid expansion “means hundreds of millions of dollars in new taxes” and would give free health care without requiring adults to look for jobs.

Whether such groups were really concerned about the fiscal health of these states is not clear. In a fine piece dissecting the effort in Idaho, Politico’s Paul Demko revealed another motive. Giving more Americans health insurance puts the country a step closer to a national health system, whether it’s called single payer, Medicare for All, or some other name yet to surface.

“I think we’re at a fork in the road,” Fred Birnbaum, vice president of the Idaho Freedom Foundation, the main group fighting the referendum, told Demko. “If Idaho and Utah and Montana [and] Nebraska and other states expand Medicaid, it will be harder for Congress to reverse that. I think that is going to put us on the path to a … single-payer system.”

In other words, if more people got used to having health insurance, it would be harder to take it away from them and stop the slide toward a universal system.

Last week word came from Idaho that Birnbaum’s group isn’t finished challenging the ability of the state’s poor to get health insurance. Spokane Public Radio reported that Birnbaum considered the wording of Idaho’s initiative problematic. He claimed the law improperly delegates authority to one state agency and his group is deciding whether to file a lawsuit to stop the expansion.

It’s still a struggle to bring health insurance and care to all Americans and may continue to be for a while. Some states that have expanded Medicaid are trying to impose work requirements on Medicaid beneficiaries. They reinforce the stereotype that those in the program are lazy, shiftless and don’t want to work. Never mind some 60 percent of enrollees are already working, many in low-wage jobs that don’t provide health insurance.

Over the last three months in Arkansas, more than 12,000 people receiving Medicaid have lost their coverage because of work requirements and won’t be eligible for new coverage until next year. If they need medical care between now and then, they must pay out of pocket or buy private insurance — an unlikely solution given the high price tag — or go without crucial care. “Taking coverage away from people who don’t meet a work requirement is at odds with Medicaid’s central objective,” tweeted Joan Alker, who heads the Center for Children and Families at Georgetown University.

Birnbaum of the Idaho Freedom Foundation may be right. More people with coverage may make it easier in the long run to establish a health program for all Americans. A lot is riding on what happens in Utah, Idaho and Nebraska as the will of the voters is carried out. And the pressure to expand Medicaid will only intensify in the 14 states that have yet to embrace the idea that their poorest residents deserve access to care.

Veteran health care journalist Trudy Lieberman is a contributing editor at the Center for Health Journalism Digital and a regular contributor to the Remaking Health Care blog.