The Marshallese fled their irradiated homeland, only to be met by the coronavirus

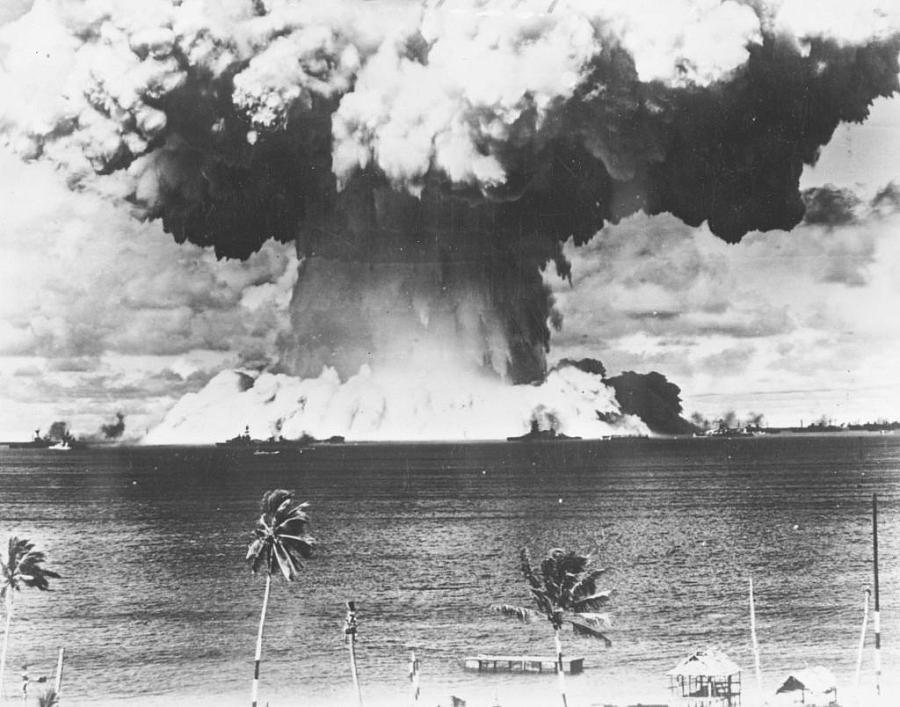

A mushroom cloud rises from the waters of Bikini Lagoon in the Marshall Islands during the United States first series of underwater atomic tests in 1946.

(Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

It's hard to tell the story of how the Marshallese came to America without starting with the nuclear bombs.

There were 67 of them, dropped on the Marshallese’ home islands in the Pacific, or tested in the ocean nearby, or even exploded from within the ground, in a 12-year stretch following World War II. Some bombs were big — and so memorable that the footage was repurposed for Hollywood's recent Godzilla remake — while others have been semi-forgotten by the Marshallese who lived through the aftermath, saying that the nuclear explosions were so frequent, the details bleed together.

All overseen by the U.S. military, seeking an advantage in the global nuclear arms race. And all affecting the Marshallese, with radiation seeping into the ground of their homes and silently hanging in the air. Scientists eventually concluded the explosions had raised the risk of cancer, and some researchers argue the nuclear campaign contributed to other health problems plaguing the island people. Adult islanders readily share tales of witnessing horrifying birth defects in person — babies with grape-size heads and transparent skin — or recount the parents and siblings who died before seeing their 60th birthdays.

By the 1980s, the United States offered the Marshallese a pact that eased their ability to relocate to America, albeit as non-citizens, and guaranteed them Medicaid to boot. But the U.S. Congress yanked their health coverage away a decade later, part of a bigger welfare reform overhaul. Lawmakers have said it was an oversight, scant comfort to the tens of thousands of Marshallese who have spent decades in America disproportionately uninsured, facing pricey health bills for chronic conditions like kidney failure and heart disease — and still grappling with the fallout of their nuclear legacy.

Meanwhile, the Marshallese have settled in pockets across America — in communities stretching from Hawaii to the heartland, with a major hub in Arkansas, of all places. Some drawn by the American dream, but others just looking to escape their irradiated home. Even today, there are parts of the Marshall Islands with higher radiation levels than the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

I've researched and written about heath care for more than 15 years. I thought I had a grasp on the disparities shaping America's health system. But the tale of the Marshallese is a story I'd

never heard, until I stood outside the U.S. Capitol on a cold, windy morning in early 2019, talking to a pair of health workers visiting from Iowa and who left me feeling gobsmacked. That conversation ultimately took me to their clinic and inside the long-running effort to restore the islanders' lost Medicaid, a fight that continues today.

Now, the Marshallese are facing another existential challenge: coronavirus.

Many Marshallese work at factories and meatpacking plants, including in communities where COVID-19 has aggressively spread. They continue to report to low-wage jobs that don’t allow them to social distance. The population is plagued by diabetes and other preexisting conditions that can cause significant complications for people who contract the virus.

Meanwhile, language barriers have complicated U.S. public health officials’ efforts to raise awareness of the virus’ risks in a community that celebrates large gatherings and shared housing. The Marshallese also continue to struggle to access health services, in no small part because of their lack of Medicaid.

Early evidence suggests that the Marshallese are now dying at elevated levels from the COVID-19 outbreak. In one Iowa county earlier this year, local officials said that the Marshallese may represent as many as 40% of COVID-19 deaths, despite accounting for less than 1% of the local population. In Arkansas, the proportion of COVID-19 cases among the Marshallese was recently estimated to be about five times higher than their share of the state population.

To these islanders, coronavirus is more than just a theoretical risk — it's a reality in many of their communities. But they're still fighting for services and support, particularly given their lack

of political power as non-citizens. Advocates for the Marshallese have pled for emergency funding that, in many cases, has still yet to come.

For this urgent project under the auspices of the 2020 National Fellowship, I'll show how COVID-19 is posing a distinct threat to this unique population, by illustrating their way of life and

how they tend to fall through the cracks in the social safety net.