Will the Supreme Court whisk us back to the bad old days when an ear infection was a preexisting condition?

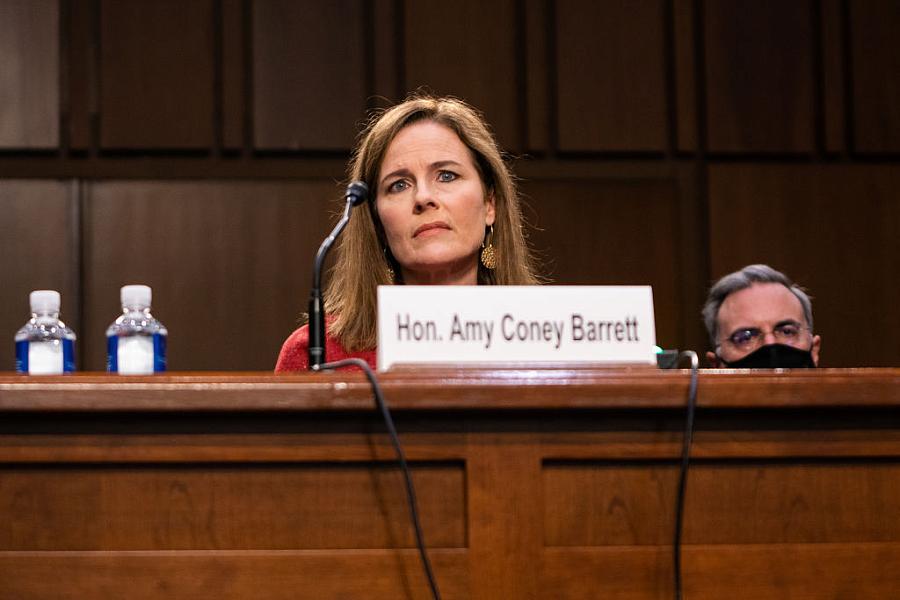

Supreme Court nominee Judge Amy Coney Barrett testifies during her confirmation hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee this week.

(Photo by Samuel Corum/AFP via Getty Images)

If Donald Trump’s “world-class” treatment for COVID-19 at Walter Reed Medical Center has shown us anything, it is the unequal treatment Americans with the disease have received for their illness. Trump received the best experimental drugs, constant monitoring, and clearly cossetted surroundings — a lot more comfortable than Americans who died at New York City’s Javits Center field hospital or at Elmhurst Hospital in Queens, where nurses begged for ventilators and one ER doctor pleaded, “We don’t have the tools that we need.”

America’s health care inequities know no geographic boundaries. In sparsely populated North Dakota, Tammy Gimbel saw her father rushed to the Sanford Medical Center in Bismarck only to find all the beds were full, as The New York Times’ Lucy Tompkins reports. They could try for care at a hospital two hours a way or delegate the care to his daughter, who was sick herself. So they resorted to a 40-foot camper trailer in the backyard where his daughter watched his temperature rise to 102 and his oxygen levels drop to 86 — deep into the danger zone. Another Bismark facility finally admitted him, and he eventually recovered after a five-day stay.

Simply put, COVID-19 has laid bare the inequities in American health care and along with it the country’s health insurance arrangements, which pay for that care. Such inequities will become even more deeply entrenched in America if the latest challenge to the Affordable Care Act, to be argued before the U.S. Supreme Court on November 10, is successful in striking down the law. University of Michigan law professor Nicholas Bagley says the law is hanging on by a thread. By which he means it’s not clear what the Court’s “center” will do. While Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was still on the court, the center, he said, was Chief Justice John Roberts, “who turned back two challenges” to the law. Now, he explained, Justice Brett Kavanaugh is the center and “we know a lot less about what he thinks.”

The Trump administration has argued that the entire law is invalid because in 2017 Congress eliminated the individual mandate requiring almost all Americans to carry health insurance. Therefore, the ACA can no longer be considered a “tax,” which was the basis on which the court found the landmark law constitutional in 2012. The administration also argued that two other provisions make the law unconstitutional.

One requires community rating, which means insurers can’t vary premiums, that make older people pay much more than younger people, for example. The ACA allows insurers to charge three times more instead of five times more, as the industry would prefer. The other provision requires insurers to sell coverage to people with preexisting health conditions, a requirement I would argue is perhaps the most important aspect of the law. That provision has made it possible for the 54 million Americans under age 65 without other insurance to gain coverage for underlying health problems — and without paying astronomical premiums.

Before the ACA took effect in 2014, Americans with the most minor of ailments could be and were denied coverage if they had to buy their own individual coverage. Sometimes they could be denied for the most minor afflictions, such as ear infections or acne. The ACA changed all that, and for the first time ever many Americans they were able to buy insurance that covered their conditions. In the bad old days, it was also common to “rider out” potential medical conditions. If you once had pneumonia, it’s possible the insurer would give you coverage but attach a “rider” to the policy saying you had no coverage for diseases of the lung. Sometimes a rider was even broader. In the case of the pneumonia patient, it could apply to all diseases of the respiratory system. In other words, Americans could often not get coverage for the very ailments they needed it for. Such insurance company practices served one major purpose: to boost insurers profits by relieving them from paying for the care of people likely to cost them money.

The plain fact is that if the law is struck down, those basic principles of insurance underwriting — that’s the term used to evaluate what kind of risk people pose to the company — will kick in once again. Right now at least 3.4 million adults younger than age 65 who’ve contracted coronavirus are likely to fall into the preexisting conditions category, according to a new study from The Commonwealth Fund, and that number will only grow. The Fund (an organization that also supports the Center for Health Journalism’s webinar series) estimates that if infections continue to grow at a rate of about 45,000 new cases a day, more than 20,000 nonelderly adults will be added to the rolls of those with preexisting conditions each day. “If the number of new cases per day of COVID-19 doubles from 45,000 to 90,000, our estimate says the number of people with a new preexisting condition could double from 20,000 to 40,000 per day,” says Eric Schneider, senior vice president of the Fund. That’s a whole lot of people, many with lasting symptoms from the virus who would suddenly find themselves stranded in insurance company purgatory.

Before the ACA, Americans could often not get coverage for the very ailments they needed it for. Such insurance company practices served one major purpose: to boost insurers profits by relieving them from paying for the care of people likely to cost them money.

Insurers have some discretion when it comes to deciding what is and isn’t a preexisting condition, Schneider points out. For example, he told me influenza was never a preexisting condition, but hepatitis C may very well become one because of the high cost of drugs to cure the disease. “COVID-19 is more uncertain. We have suspicions it’s leading to long-term health effects, but in many cases it would be difficult to tie a condition to COVID-19,” he said. In those cases, Schneider added, an insurer would be more likely to deny coverage than “rider out” the condition. “Science is still sorting out the long-term effects and what they are, but without the ACA, insurers will have tremendous discretion in what they accept and what they decline.”

Overturning the ACA is likely to heavily impact today’s younger adults, a group that accounts for a large share of infections over the summer. A new study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that Americans now in their 20s account for more COVID-19 cases than any other age group. In May, the number of cases of people between 20 and 29 totaled about 93,700. By August, it had risen to more than 189,000.

Without the ACA’s protections against preexisting conditions, it’s conceivable that an insurer could ask a young person — or any person for that matter — applying for coverage in the individual market whether they had tested positive for COVID-19. If they are truthful and answer “yes,” they could be declined, since the insurer may assume potentially costly long-term side effects that have yet to reveal themselves. If they answer “no” but have had the disease and the insurer finds out when they file a claim, the carrier can refuse to pay the medical bills, a practice called “post-claims underwriting.”

Because of the potential threat of being permanently frozen out of the insurance market, Schneider says letting the disease spread among the young is a “dumb approach” for that reason alone.

Should the Supreme Court vote to overturn the Affordable Care Act and its requirement that insurers must cover someone regardless of their health status comes, it would come at the worst possible moment. The virus has already begun to poke large holes in the insurance offered by employers — the place where about 156 million Americans get their coverage. As I noted in a recent post, insurance coverage from employers, especially small employers covering only a handful of workers, is increasingly costly. Many small employers are considering whether to offer coverage or give their workers an allowance to buy coverage in the marketplace on their own. If employees take their employer’s coverage, they could face very high premiums, especially if the company’s workers or their family members insured under the plan have had COVID-19. You can bet the insurance carrier will be asking employers about their workers’ history with the virus. On the other hand, if workers set out on their own on the individual market, they could soon find out their health history is a deal-breaker.

Says Schneider: “The small group market is a ticking time bomb.” And it’s ready to explode if there’s the Supreme Court votes to torpedo the ACA and bring more health care inequities to an already inequitable system.

Veteran health care journalist Trudy Lieberman is a contributing editor at the Center for Health Journalism Digital and a regular contributor to the Remaking Health Care column.