Insurance costs are rising, but putting sick people in separate risk pools isn’t the answer

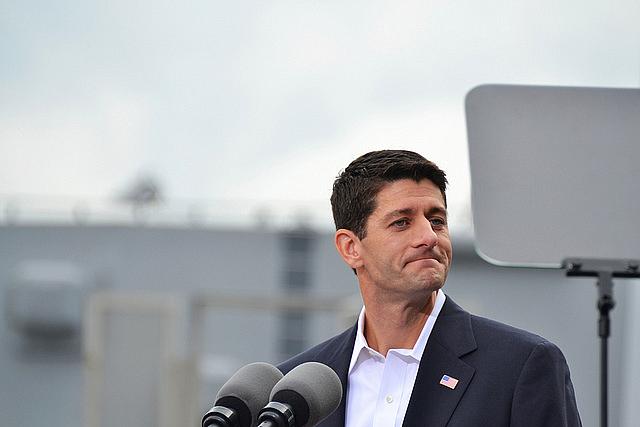

House Speaker Paul Ryan recently proposed the creation of separate high-risk pools to insure sick people as a way to lower costs for everyone else.

A nagging contradiction in the Affordable Care Act has finally become visible. During the debate on the health care law, commentators, including me, continued to ask this question: How can for-profit insurance companies whose bottom lines are based on risk selection — the ability to cover only the healthiest people unlikely to run up big medical bills — make money when they have to insure the very sickest Americans. At the time few people wanted to address that question instead dismissing the questioners and essentially saying, “Don’t worry, there are plenty of safeguards built into the law to help insurers ride the rough stretches.” Besides, insurers would do the right thing because they were getting tons of new business from the previously uninsured.

So far it hasn’t worked out that way. The Blue Cross Blue Shield Association reported earlier this year that newly insured Americans under Obamacare had medical costs that were 22 percent higher than costs for people who received coverage from their employers. The consulting firm McKinsey & Company found that carriers lost money in the individual market (that includes Obamacare policies) in 41 states in 2014 and were profitable in only nine. UnitedHealthcare, the country’s biggest insurer, has said it will not sell Obamacare policies in most states, and Humana, another biggie, says it might leave markets, too. In many areas of the country, United’s exit means only one or two insurers are left, but then again, consumers in many counties have had the choice of only one or two carriers from the beginning.

Next year rate increases are coming. The neutral American Academy of Actuaries puts it this way: “There are both upward and downward pressures on premiums for 2017, but for individual and small group markets as a whole, the factors driving premium increases dominate.” The biggest reasons: higher health care costs and the end of a reinsurance program called for in the law to help carriers prop up their losses.

We’ve yet to reach the promised land of insurance rate stability. The question remains: What’s to be done to resolve that nagging contradiction between expanding coverage and keeping insurers in the game?

Higher premiums will no doubt cause policyholders to search out the cheapest plans, which usually come with very high deductibles, high copays, and high coinsurance. But making middle-income policyholders pay more out of pocket is not much of a solution. It’s a trade-off that leaves them underinsured, which wasn’t exactly one of the objectives of the Affordable Care Act. A serious illness still could mean medical bankruptcy, another possible consequence the ACA was supposed to avert. That was also not commonly discussed in those heady days of 2010.

We’ve yet to reach the promised land of insurance rate stability. The question remains: What’s to be done to resolve that nagging contradiction between expanding coverage and keeping insurers in the game?

One idea for curbing rising premiums was proposed by House Speaker Paul Ryan a couple weeks ago, when he announced his “back to the future” solution — high-risk pools to insure sick people. That old remedy, similar to high-risk pools for bad drivers, goes back decades and was promoted by the insurance industry as a way to cover sick people, maintain the carriers’ ability to select the best risks, and keep the prospect of national health insurance from the door. “Less than 10 percent of people under 65 are what we call people with pre-existing conditions, who are really kind of uninsurable,” said Ryan. “Let’s fund risk pools at the state level to subsidize their coverage so that they can get affordable coverage. You dramatically lower the price for everybody else.”

Such a proposal would move those who are sick to their own risk pool where prices will be super high and coverage super skimpy, which was the case with the risk pools of old and why they were not wildly successful at covering the hard-to-insure. The ACA called for interim risk pools after the law was passed to provide a way for sick people to get insurance before the 2014 start date for the law, but they never were a big draw. The government estimated that at the end of 2010, 375,000 people would sign up, but in mid-2013 only 220,000 people were in the pools. Whether the risks pools work or not, if insurers can shed sick people from their rolls, charge lower premiums to customers who remain, make their offerings more competitive, and in the end turn a profit from Obamacare.

It’s a good bet that Blue Cross organizations and other carriers are talking to Ryan and various friends on Capitol Hill. Proposals such as Ryan’s could boost their profits. Many ideas could be in play once a new Congress comes to town. The GOP is working on a policy agenda document to be released before their July nominating convention. You never know what schemes to eliminate the central core of Obamacare — allowing everyone access to coverage no matter how sick they are — might pop up and eventually get tacked onto some must-have legislation such as a budget bill. It’s possible that other remedies, such as making the sick pay higher premiums for their coverage, could also re-emerge. Maybe even the reinsurance program could be restored, but that would come at a cost to the Treasury.

The underlying problem is two-fold. Not every American eligible for coverage has entered the risk pool as the ACA had envisioned. Many young people and those who can’t afford the cost of insurance, including premiums and high cost-sharing, are taking a pass. “Healthy people aren’t buying,” says Washington insurance consultant Robert Laszewski. In many other countries, everyone is in the risk pool, making it possible to distribute the risk and deliver care to everyone at a somewhat reasonable cost. A sicker pool of insurees means more expensive premiums for all.

The second problem hinges on the way policymakers have chosen to control costs, which will continue to rise thanks to ever-increasing drug prices, new technologies, and all the newly insured who are using medical services. Massachusetts faced a rising cost problem when it passed its reform in 2006. It still hasn’t solved it.

While there are experiments here and there aimed at controlling medical costs, it’s not clear whether they will do that, and stronger measures may be needed. But those measures, like controlling the cost of services or using technology more carefully, are anathema in the U.S. As one health expert put it, we have to do things that are “compatible with our values.”

Still, next year’s debate must move beyond the silly ideas of siphoning off sick people into dysfunctional risk pools or wiping out the guarantees of coverage promised by the ACA. How that nagging contradiction gets solved will determine if Obamacare will survive for the long haul.

Veteran health care journalist Trudy Lieberman is Contributing Editor of the Center for Health Journalism Digital and a regular contributor to the Remaking Health Care blog.

[Photo by Tony Alter via Flickr.]