It’s time for reporters to cut through the spin on plans to lower drug prices

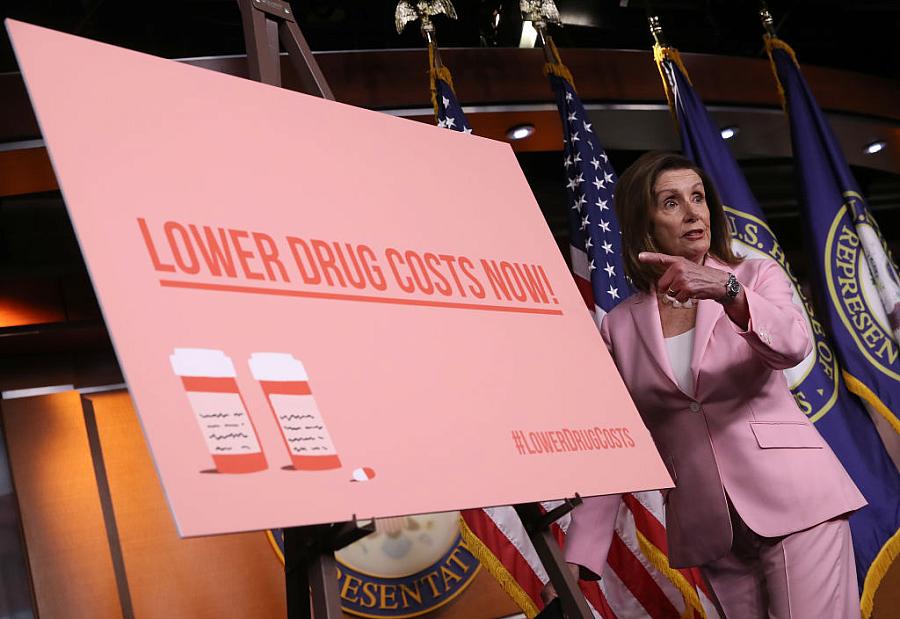

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi at press conference in September, where Democrats introduced their plan to lower prescription drug prices.

(Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

Health care has become the number one pocketbook issue, an observation confirmed by Kaiser Family Foundation’s latest tracking poll. Seventy percent of the public say that lowering prescription drugs should be a top priority, and 64% believe that reducing what people pay for care in general should also be a top priority. In other words, Americans want something done to lower the cost of getting sick.

It looks like maybe — just maybe — some members of Congress are willing to help out by slaying one of the country’s sacred cows — the pharmaceutical industry, which has managed for decades to deflect most criticisms of its business practices. Until now. Gallup’s annual Work and Education Poll, conducted in August, shows the drug companies ranking dead last in Americans’ views out of a list of 25 U.S. industries. Big pharma’s ratings in the poll, which Gallup has been doing since 2001, have never been lower.

Its dismal showing and loss of stature is less than surprising when you think back on a public fed up with high drug prices, relentless advertising pushing new pills, Purdue Pharma’s role in spawning the opioid crisis, and stories of young people dying because they can’t afford their costly insulin. Together, these storylines have tarnished the industry’s image.

Indeed the industry itself sees the need for “Flipping the Script,” the title of what was billed as an “intimate roundtable event” produced by MM&M, a medical marketing publication. By flipping the script, the drug industry apparently means ginning up its basic message — drugs improve and save lives — that has bought the industry so much cover over the years. “Rising prices have negatively impacted people’s perception of pharma and overshadowed the good that the industry is doing,” observed one attendee.

This time, though, it may be Congress that is flipping the script. Iowa Republican Sen. Chuck Grassley has teamed up with Oregon Democrat Sen. Ron Wyden to sponsor a bill that could begin to disrupt the drug industry’s way of doing business.

“Eventually it will come down to this,” said Grassley. “There are 22 Republicans up for election this year and if it’s like in my state … there is a great deal of disgust with the rapidly increasing prices of drugs.” Passing a bill to control drug prices will be essential for Republicans in “keeping a majority in the Senate.”

In Grassley’s view, Republicans need to pass something to quell the public outrage about high drug prices. And he’s arguing that the political need outweighs the political clout of pharma’s lobbying phalanx. That’s a promising message from a Republican Senator.

On the other side of the aisle, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s drug pricing bill calls for the federal government to negotiate each year for up to 250 of the most expensive drugs that do not have at least two competitors. The negotiated prices would be available to all purchasers, not just Medicare. The prices would be pegged to the cost of the same drugs in other countries using an international pricing index. If drug makers refused to negotiate, they’d be subject to steep fines beginning at 65% of the gross sales of the drug. Pelosi’s plan would cap Medicare beneficiary spending for their drugs at $2,000 annually. Money taxpayers saved would be plowed into drug research at the NIH.

But is it just a bunch of hot air? I checked in with David Mitchell who probably knows more about this from the consumers’ side than anyone. In 2017 Mitchell, a cancer patient who once was a public relations executive, founded the advocacy group Patients for Affordable Drugs, which has since collected nearly 20,000 stories of Americans who’ve had trouble affording their medications. Some of them have shared their experiences with Congress.

“The fact that we have gotten this far, and there’s still meaningful talk of getting something done is remarkable,” Mitchell told me. He had been on the Hill testifying the day before our conversation. “Some members (of Congress) said our voters are saying we have to do something about prices.” He added, “the anger is really boiling up and elected officials know and feel this anger could cost them their jobs if they don’t do something.”

What is the “something” that Congress might pass? How much does the public really know about the policy options and how they would work in a news cycle relentlessly dominated by talk of Trump and impeachment?

So far most of the “explanations” of possible Congressional solutions are coming from the drug industry itself, which has embarked on a long-term strategy of fighting back with its 1,359 lobbyists, $156.7 million in political campaign contributions and its usual message that drugs save lives and improve health. Many of the messages sound like this one from Politico Pulse:

“Speaker Pelosi’s radical plan threatens the United States’ position as the global leader in developing lifesaving treatments and cures. It upends the successful Medicare Part D program 45 million people rely on. There are far more practical solutions to improve affordability.”

Sponsored content such as this is aimed at lawmakers and political influencers. It’s designed to make sure that Congress doesn’t pass anything that would disrupt their business practices.

"The fact that we have gotten this far, and there’s still meaningful talk of getting something done is remarkable." — David Mitchell, Patients for Affordable Drugs

Sponsored content on the daily news brief Axios Vitals does the same. Pharma urges readers to “Get the Facts on Speaker Pelosi’s Plan” and notes that the plan “is the wrong approach for patients & American innovation.” One of the “facts” it shares with readers: “FACT: Speaker Pelosi’s drug pricing plan would siphon $1 trillion from biopharmaceutical innovators over the next 10 years, putting at risk the development of new medicines for serious diseases like Alzheimer’s, cancer and ALS.”

Compounding matters, statements from a front group called Seniors Speak Out are likely to confuse the public even more. The group was created by the Healthcare Leadership Council as a resource for older Americans, caregivers and advocates to make sure seniors have access to high quality health care, according to its website. The group’s members, however, include some of the drug industry’s giants like Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Pfizer, and Bristol Myers Squib.

By now the public must be getting very confused. That’s why we need better media stories — or any media stories for that matter — that sort through the proposals and give basic nuts and bolts descriptions of what the major solutions for reforming the drug industry would do and most importantly how they would affect their pocketbooks. After all, as I’ve pointed out earlier, this is Pocket Book Issue Number One for American families.

Some of the major solutions on the table include:

Negotiating drug prices in the Medicare program would be a huge step toward helping seniors pay for their drugs. The 2003 law that gave seniors the Medicare Part D drug benefit prohibits Medicare from negotiating prices with pharmaceutical manufacturers. That makes the U.S. the only developed country in the world that imposes such a restriction.

Capping out-of-pocket costs for seniors might encounter the least opposition. Pelosi’s bill would limit those costs to $2,000 a year while the Senate bill introduced by Grassley and Wyden caps those expenses at $3,100.

Reference pricing, a process for pricing drugs in line with what people in other industrialized countries pay, is also a controversial idea. U.S. drug prices are two to three times higher than those in most other nations, and a reference pricing system based on some international benchmark would likely lower costs for patients.

Changing the patent laws would encourage more market competition and make it easier for generics and biosimilar drugs — similar versions of medicines made from living microorganisms found in plant or animal cells — to come to market.

Injecting more transparency into the system of pharmacy benefit managers, those mysterious middlemen between insurers and drug makers, might help reveal how prices are set. Pharmacy benefit managers help cut secret rebate deals that determine what patients ultimately pay.

Mitchell shared with me some research done for his group by the polling firm Hart Research Associates. Focus groups conducted of swing voters in Iowa and Colorado among 34- to 54-year-olds and among voters 55 and older in September found very positive reactions to allowing Medicare to negotiate with drug companies, limiting out-of-pocket costs for people on Medicare to no more than $2,000 a year, and ensuring that all Americans see lower drug prices, regardless of their insurance. Pollsters also found that before the focus groups were conducted, most swing voters did not know that Medicare is not allowed to negotiate directly with drug companies, or that the U.S. is the only developed country with such a ban. Swing voters believe that drug companies charge high prices because they can and that there are no sufficient market or regulatory forces to stop them.

Such findings suggest the public has lost its appetite for the status quo when it comes to prescription medicines. They just need some honest, in-depth consumer reporting to make sense of the debate — the kind that did away with credit card abuses and the kind that forced lenders to disclose the true rate of interest they were charging for loans and credit cards. Reporters have an important task ahead. And editors need to give the issue the coverage and placement it deserves, even it means moving over a few impeachment headlines now and then.

Veteran health care journalist Trudy Lieberman is a contributing editor at the Center for Health Journalism Digital and a regular contributor to the Remaking Health Care column.