For Obamacare's uninsured holdouts, it's all about the money

Has the ACA lived up to this promise?

The story of the Affordable Care Act is a tale in two parts. One is about those who have insurance. The other is about those who don’t.

With the third open enrollment period closing last Sunday and the Congressional Budget Office predicting that fewer people will sign up than expected, it’s time to be honest about why it’s so hard to get the holdouts to sign on the dotted line. The answer can be found at the intersection of idealism and the real world of family budgets stretched thin. Their reluctance is all about money.

A week ago, as the president was telling Americans in his weekly radio address that the law provides “affordable, portable security for you and your loved ones,” news coming from Ohio and Colorado told a different story — one of less security and unaffordable insurance. Raymonia Lacy, an Obamacare navigator, made it clear in the Columbus Dispatch that affordability seems to be the primary sticking point for people. Premiums have been higher than in other parts of the country — so high that Ohio’s enrollment rate has been one of the lowest in the nation. In Colorado, “the new era of affordable health care” has “bypassed” many Colorado citizens, especially those living in the state’s mountain counties, where premiums, always on the high side, are now out-of-reach, The Denver Post reported. “We’re at the breaking point crisis state up in the resort communities,” Summit County commissioner Dan Gibbs told the paper. “People are deciding whether they’re going to pay rent or buy health insurance or pay for day care.” Health insurance premiums are as high as mortgage payments, sometimes exceeding $2,000 a month.

What happened to “affordable quality health care for all” that supporters of the Affordable Care Act promised? To answer that, it’s important to understand that at its core, the ACA is a welfare program with tax subsidies that help make private coverage affordable. Last year, nearly 90 percent of Obamacare enrollees needed help. The law was never intended to give subsidies to everyone. That was too expensive. Congress knew there would always be millions of uninsured — about 30 million, the Congressional Budget Office once estimated. There would always be casualties in a costly private insurance system that relies on means testing to determine who wins the prize, and like all welfare programs, there will always be people over the line for eligibility.

Who are these millions for whom the prize of health insurance is out of reach? As the Denver Post reported, many are up in the Colorado high country, but they are everywhere else, too. The paper cut to the chase. “The problem is that the cutoff for (subsidy) eligibility slices right through the middle class,” it reported, noting that a 55-year-old couple in Garfield County with no children who earned $63,000 could be eligible for as much as $13,200 in annual tax subsidies. But if they earned $64,000 or more, they may not qualify for any credit.

Those over the line (even by a smidge) may decide the tax penalty is not as bad as the cash penalty for buying insurance, says Dr. Martin Serota, chief medical officer of Los Angeles-based AltaMed Health Services, one of the country’s largest federally-qualified health clinics. “It’s cheaper to go bare and keep your fingers crossed,” he told me. “That’s not uncommon at all.” While the ACA cut in half the number of uninsured patients coming to his clinic, Serota said 10 percent are still without coverage.

Some are undoubtedly trapped in the so-called family glitch. To save money, the government chose to deny subsidies to family members of workers whose employers pay a good chunk of their health premiums. Family members who are not on the employer plan (mostly because workers can’t afford to put them on) can’t get exchange subsidies if their spouses pay less than 9.56 percent of the family’s household income for their employer coverage.

That’s a dilemma for 53-year-old Laura B. who lives in northwest Illinois. Her husband’s Social Security and pension income disqualifies her. The $618 he pays for his coverage is considered “affordable” by the government and below the 9.56 percent cutoff for help. This year, the premium for her gold plan is $750. She pays $500 from what’s left of her savings and a divorce settlement, and her husband, a former firefighter now terminally ill with respiratory disease, had to sell one of his stocks to help her pay the rest.

Elisabeth Benjamin, vice president at New York City’s Community Service Society, has signed up hundreds of New Yorkers for coverage. Other than legal immigrants in families with undocumented relatives, she said, the no-takers fall into two groups. One are young adults who don’t see the value of insurance, and the other group includes those who are eligible for subsidies, but calculate that even with them, insurance is not a good buy.

As if the yearly cost of $9,000 isn’t enough, the policy comes with a 70/30 split, meaning the insurer covers 70 percent of the bills until she reaches the maximum out of pocket amount of $5,250. The 30 percent she pays is slowly draining what savings she has left. “What the hell am I going to do next year when I’m tapped out?” she asks. A Blue Cross Blue Shield customer service rep told her to get a job. She can’t right now, she says. Her husband needs round-the-clock care.

Who else is skipping out on insurance? I circled back to Elisabeth Benjamin, a vice president at New York City’s Community Service Society, who has signed up hundreds of New Yorkers for coverage. Other than legal immigrants in families with undocumented relatives, she said, the no-takers fall into two groups. One are young adults who don’t see the value of insurance, and the other group includes those who are eligible for subsidies, but calculate that even with them, insurance is not a good buy.

“There are a lot of people eligible for subsidies, but what they can buy feels unaffordable because they have competing needs,” Benjamin told me.

Last year, the average subsidy was $283. When premiums for family policies run $900 or $1,000 a month, coupled with requirements to satisfy high deductibles and high coinsurance amounts, their reluctance is understandable.

Sara Collins, a vice president at The Commonwealth Fund, says subsidies “substantially reduce out-of-pocket costs for people with incomes under 200 percent of poverty ($48,000 for a family of four), but there’s a significant cost exposure to people in the middle income range.”

A new study from The Urban Institute quantified that exposure. Ten percent of families who sign up for 2016 policies with incomes less than 200 percent of poverty will pay at least 18.5 percent of that income for premiums and out-of-pocket medical costs. Ten percent of those with incomes between 200 and 500 percent will spend more than 21 percent.

That’s some burden. Consider a family with an income of $65,000, a bit more than the U.S. average, which is offered a $400 monthly premium after a subsidy is applied. “Do they have an extra $400 in the monthly budget, or about $5,000 a year, in the family budget?” asks Washington insurance consultant Robert Laszewski. “The answer is no.”

And when the yearly out-of-pocket maximum on expenses is figured in, it’s easy to see why taking the penalty is cheaper. HealthPocket reports this year’s average out-of-pocket maximum for silver plans (on which the subsidies are based) is now $12,270 for family plans. The average silver plan premium for a couple, both aged 40, with two children, aged 10 and 12, is $1,019, according to HealthPocket.

The burden of these costs on family budgets is showing up in other stats. For the second year of enrollment, the consulting firm Avalere Health found that 76 percent of those with incomes between 100-150 percent of the poverty level signed up. But only 30 percent of people with incomes between 201-250 percent of the poverty level chose insurance, while just 20 percent of those with incomes between 251 and 300 percent did.

The final numbers from this year’s enrollment will be out the end of March, and it’s now nail biting time for those worried about the sustainability of the Obamacare exchange marketplace. Laszewski believes the final number will not be much higher than the 11.7 million reported at the end of February 2015 — later reduced by the government to 9.9 million at the end of June.

If fewer people sign up, that could begin a cycle of ever-higher premiums and more out-of-pocket expenses for families, not to mention the uncertainty. “I don’t know what’s going to happen next year,” Laura B told me. Budgets can only stretch so far.

Veteran health care journalist Trudy Lieberman is Contributing Editor of the Center for Health Journalism Digital and a regular contributor to the Remaking Health Care blog.

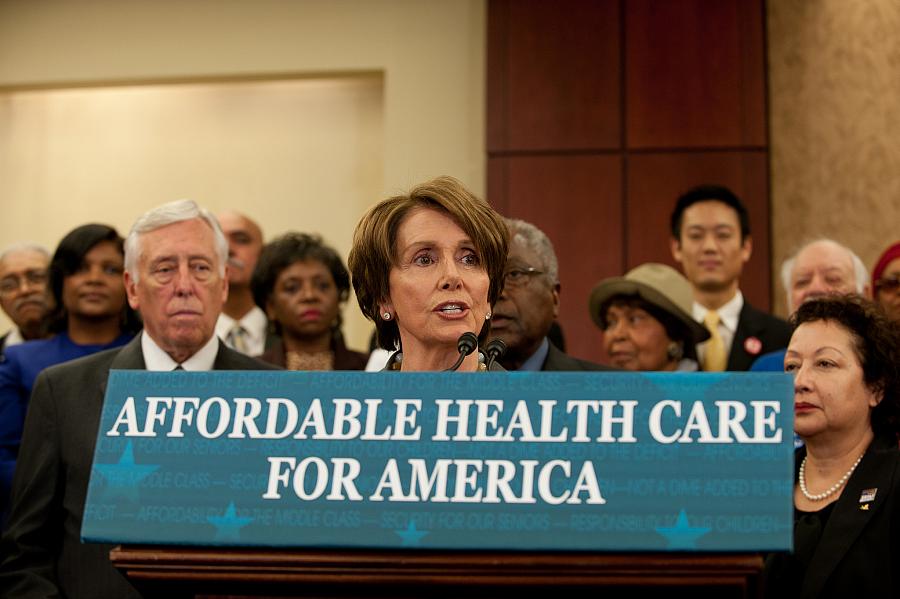

[Photo by Nancy Pelosi via Flickr.]