The rising costs of employer-based insurance is a huge story ‘hiding in plain sight’

iStock

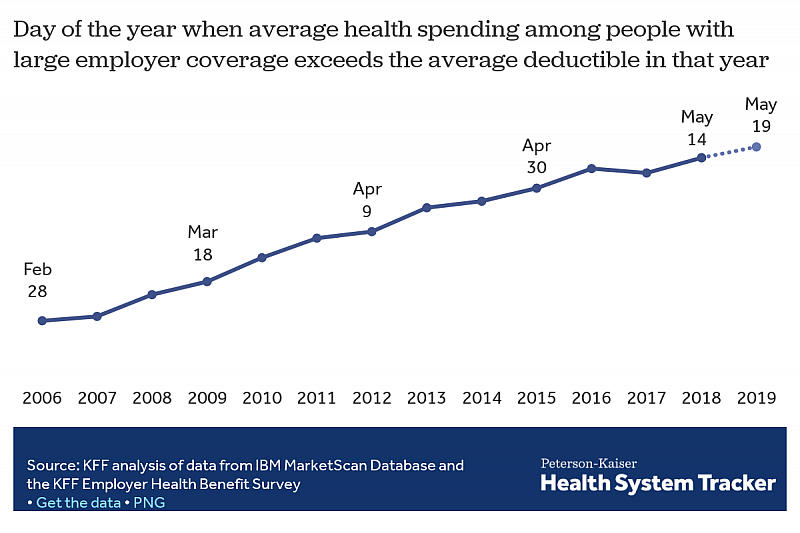

Every year, “Deductible Relief Day” gets pushed back a little later.

The term, coined by researchers at Kaiser Family Foundation, marks the day when people with employer-based health insurance meet their deductibles. In 2006, patients were paying out-of-pocket for their medical expenses on average until February 28. That year, the average deductible for single coverage was $303.

By 2018, deductible relief didn’t come until May 14, and the average deductible had risen to $1,350. Meeting those high deductibles is a growing struggle for many low- and middle-income workers with job-based coverage.

“If you don’t have the money to cover a deductible, your insurance in many ways feels like ‘uninsurance’ to you,” said Larry Levitt, KFF’s executive vice president for health policy, during CHJ’s recent Health Matters webinar.

It’s part of a growing trend that has been “hiding in plain sight,” said Noam Levey, national health policy reporter for the Los Angeles Times. Job-based health plans are getting too expensive for many workers, with some families forced to choose between forgoing groceries or prescriptions to pay medical bills.

Levey has explored their stories in an ongoing series for the Los Angeles Times, based on a survey of adults with employer coverage jointly conducted by the Los Angeles Times and KFF. The two organizations developed the questions together, and the results helped fuel Levey’s stories.

“We spent so much time covering Obamacare and the politics of health care in Washington, and we felt we were missing this story,” Levey said.

Forty percent of respondents said they — or a family member — had experienced challenges in affording health care in the last year. Seventeen percent said they had to make a difficult sacrifice in order to pay for health care and insurance costs.

Levey also partnered with the Health Care Cost Institute to explore how workers were utilizing their high-deductible health plans and the Employee Benefit Research Institute to better understand the use of health savings accounts.

But in order to bring the survey findings to life, Levey needed stories from real people. Some poll respondents indicated that they were willing to speak with a reporter, and the survey was designed to generate reporting leads. But the veteran health policy reporter leaned on other sources as well. In an effort to find people who were dealing with chronic conditions, he contacted organizations such as the American Cancer Society. Using an online call-out, the Times asked readers to share their stories.

“We all knew deductibles were rising dramatically (and) that people were having trouble paying their medical bills,” Levey said. But “when you actually saw the kinds of things people said they were doing — like going without food or thinking twice about taking their kids to the doctor — it sort of added a level of poignancy to what’s happened with health insurance over the past 10 to 15 years.”

Good care can cost less than it does now, said Dr. Arnold Milstein, medical director of the Pacific Business Group on Health. Over the past several decades, the health sector has tried several remedies to address the soaring cost of insurance. Nothing has worked as hoped. Health care per capita spending continues to outgrow money that is coming in to pay for health care, Milstein noted. This “diminishes wages and employment growth in industries outside of health care,” he said.

To pay for medical bills, many people are turning to charity. Levey scoured GoFundMe pages to illustrate the trend for an upcoming piece for the Times’ series. Another story will look at patients who try to “shop around” for medical care.

The results of the KFF/L.A. Times poll continue to inform his reporting. However, while the Times and KFF worked together closely on the survey, KFF had no editorial influence on the stories themselves, Levey said.

“For any analytic organization or think tank wanting to enter a partnership like this ... you have to go in recognizing that the news organization has to have full editorial control,” said Levitt, who worked closely with Levey. “That’s the only way it can work.”

Tips from the webinar for reporters:

- Keep tabs on academic research. During the webinar, Levey highlighted cited research that had already been done on the rising cost of employer-based health insurance. But fewer people are reading academic journals. It’s a reporter’s job to stay informed, use people’s expertise, and make the research come to life for a broader audience.

- It’s not “necessary to do a big national poll to get at what’s happening at communities across the country,” Levey said. Find local stories to bring to life national polls such as the KFF/Times poll. But don’t be reluctant when it comes to approaching researchers or forming partnerships. They might even be willing to do data runs more relevant to your coverage area.

- Ahead of the 2020 presidential campaign, ask voters how they feel about their job-based health plans. About 156 million people in the U.S. have employer-sponsored plans. In the KFF/L.A. Times poll, 72% said they were “grateful” for their coverage, and 69% said they were “content.”

- As employees are paying more out of pocket, consider how employers in your town are dealing with a shifting health insurance industry. There’s a sense among many employers, particularly those with low-wage employees, that shifting a greater share of costs on to employees had reached its limit, Milstein said. But “not all feel that way,” he added.

- Keep an eye on the political fight to protect people from surprise medical bills. California’s legislature is trying to expand protections for patients, but the hospital industry is pushing back. “As we debate large changes like ‘Medicare for all,’ it’s important to remember that health care industry groups are still quite powerful,” Levitt noted.

Ashley Nguyen is a freelance journalist who previously worked at The Washington Post. She is currently pursuing her MPH at the University of Washington.