As Senate rushes ahead, the missing debate over Medicaid poses dire risks for rural, elderly Americans

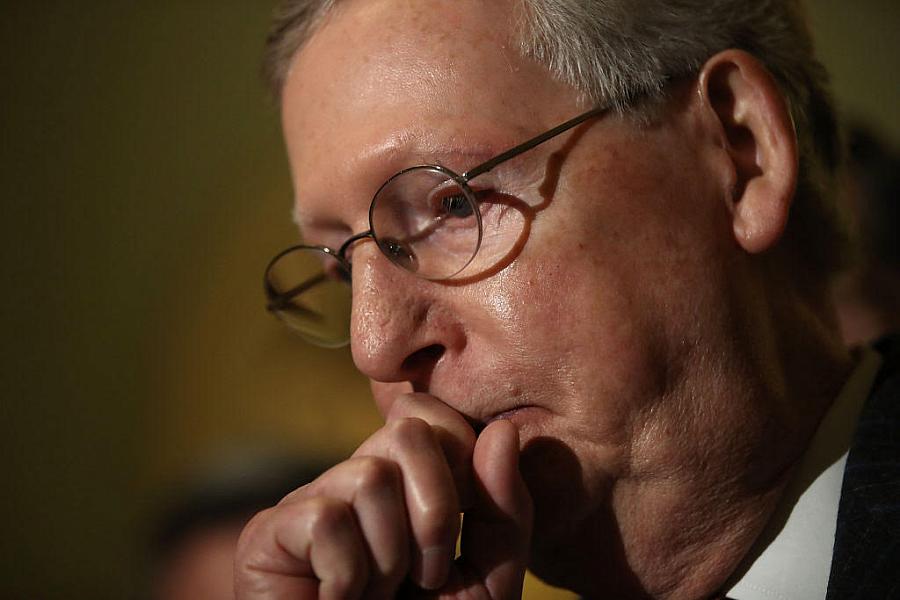

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and fellow Senate Republicans unveiled their health plan on Thursday, which includes a major Medicaid rollback.

Has the conversation swirling around replacing the Affordable Care Act focused on the wrong thing?

For weeks the steady stream of tweets, studies, numbers, and pleas to save Obamacare has largely focused on the people who gained coverage through the health law’s state insurance exchanges. But under the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, in my view the most important feature of the law, far more people gained health insurance coverage. For millions of people, that was the first time in their lives they got insurance and care they never had before.

While those in the Medicaid expansion group have not been ignored totally, focus still has been on the 12.2 million who signed up for Obamacare policies this year. “Medicaid expansion and poverty is a very underreported story,” Washington University professor Timothy McBride told attendees at a rural health workshop a few weeks ago sponsored by the Association of Health Care Journalists. “The Medicaid story is huge,” McBride said. Enrollment went from nearly 57 million in 2013 million to almost 75 million in 2017.

(Recall that in states that expanded Medicaid, the ACA provides coverage for all adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. That’s $16,643 for a single person and $33,948 for a family of four. It’s tough to put food on the table, pay the rent, and buy health insurance with incomes that low.)

You would think such an achievement in improving the health and well-being of so many citizens would be something to celebrate — perhaps something akin to the excitement expressed when Medicare became law in 1965, making it possible for millions of old people to get health insurance and medical care at a time in life when their incomes and health had declined. Instead, Medicaid has become something to tear down, emerging as the central focus of Republican attempts to rid the country of the Affordable Care Act. “Medicaid is growing at an unsustainable pace,” said Pennsylvania Sen. Pat Toomey recently. “If we’re going to overhaul this program which we need to do by virtue of Obamacare, we can at least put it on a sustainable path.”

For Congressional foes of Medicaid, that sustainable path means dropping some 14 million people from the rolls by 2018 — the CBO’s estimate of how many people would lose coverage under the bill the House passed in May. That number alone should also have been enough to pique more interest. It didn’t.

I asked McBride more about this. “You hear Medicaid is not really insurance coverage,” he told me. “People think of it as lesser coverage because sometimes there’s less access to providers.” But in reality it covers a lot of things. Sometimes it covers a lot more than some policies sold in the traditional marketplace.

But there’s another reason: Medicaid carries the stigma of being a welfare program, and Americans don’t like welfare. Typical of that sentiment is one email I received earlier this year from a man in the Midwest, who said, “I LOVE the idea of Medicaid reform. We can save millions, probably billions by putting people to work who can work and sending people who won’t comply back to their own country.” Results of a recent tracking poll from the Kaiser Family Foundation reinforces that belief. The poll found that about one-quarter of Democrats viewed Medicaid as a welfare program, but about half of Republicans did. Those numbers explain a lot about the current debate.

The untold story of Medicaid that worries McBride is more nuanced. It is the proverbial tale of two cities. Although the ACA brought an historic drop in the numbers of uninsured Americans, those numbers show very different results for insurance coverage in urban and rural parts of the U.S. Rates of uninsurance for non-elderly adults dropped 42 percent in urban areas compared to 39 percent in rural communities between 2010 and 2015. “Rural people are disproportionately living in states that did not expand,” McBride explained. While both groups will be out of luck if the GOP succeeds with its plans to repeal and replace the ACA, those with Medicaid coverage in rural areas will be hurt the most.

That’s even more concerning when you consider those same rural residents are particularly affected by the social determinants of health — lack of good housing, poor transportation, few options for healthy foods, and above all, a lack of jobs.

Janice Probst, director of the South Carolina Rural Health Research Center, adds another dimension to the urban/rural Medicaid split. “There’s a substantial minority presence in rural America,” she told journalists at the AHCJ workshop. I chatted with her after her session finished. “Failure to expand Medicaid is a great way to selectively cause the death of persons of color,” she told me.

Medicaid’s untold story also includes Americans who have received benefits under the traditional Medicaid program — for example, the millions of middle class families who’ve come to rely on it to fund long-term care for a family member. Medicaid pays for about half of all nursing home stays. That’s another subject that’s been missing from the media until this past week. GOP proposals to slice more than $800 billion from the Medicaid program mean that states will have much less money to funnel into nursing home and other forms of care for the elderly in their communities. Where are the media stories on this? Where are protests from families who would be affected?

Time is running out to change the conversation. The Senate’s health reform bill is expected to be revealed today, with a vote as early as next week. “This is the most consequential change in 50 years for low-income people’s health — a massive change that has hardly been discussed,” Joan Alker who directs the Center for Children and Families at Georgetown University, told The New York Times. As the Times headline — “G.O.P. Health Plan Is Really a Rollback of Medicaid” — signaled to readers, the Republican health care plan is really about rolling back Medicaid. Indeed it is, and as a potential rollback rumbles through America, rural and elderly citizens will be hit the hardest by its aftershocks.

Veteran health care journalist Trudy Lieberman is a contributing editor at the Center for Health Journalism Digital and a regular contributor to the Remaking Health Care blog.

[Photo: Win McNamee/Getty Images]