Telling patients to haggle with hospitals doesn’t help us halt ‘surprise bills’

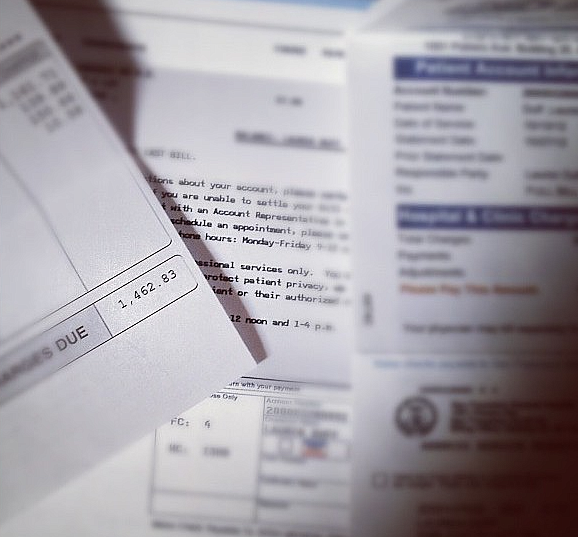

Not long ago David Bordewyk, executive director of the South Dakota Newspaper Association, called me to complain about the media. Earlier in the day he had heard a discussion on CBS This Morning about a growing and vexing problem facing too many Americans: humongous hospital bills they can’t pay. In most cases, they shouldn’t have to pay them since insurance plans have already reimbursed the hospitals. But many patients get caught in the trap of “surprise” medical bills that can leave them with thousands of dollars to pay out-of-pocket. The latest Kaiser Family Foundation tracking poll found that surprise billing is the biggest health care issue heading into the election.

It wasn’t just the unfairness of such bills that bothered Bordewyk, but also the advice consumers watching the show received. The suggestion was that patients should negotiate with their hospitals, a tactic that has worked for some people in bringing bills down to more manageable levels. But as a strategy for solving this consumer problem, Bordewyk thought it was lame. “That advice seemed useless to me and insufficient,” he said. “It seemed so lacking, it was frustrating.”

“How are we as consumers supposed to negotiate with this giant entity over a bill?” Bordewyk asked. “It seems like trying to haggle with the IRS. Good luck. You are in a position of vulnerability.” Bordewyk posed this question: Why do we heap such burdens on sick people just out of the hospital? He told me he didn’t know the answer, but he knew that haggling with the hospital wasn’t much of a solution.

The CBS segment meted out what passes for standard consumer protection advice these days. It noted that 21 states have surprise billing laws, which don’t work very well, but nevertheless advised viewers to check the laws in their states, and always fight back.

Bordewyk’s disbelief was spot on. If someone followed the CBS program’s advice to negotiate, most would come up empty-handed.

About the time of Bordewyk’s call I had begun researching what state laws are on the books to make hospital prices more transparent. Readers of these columns know I am not a big fan of shopping for health care services, and shopping for hospital care is impossible once you are a patient. Still, in a previous column I also argued that while the current crop of stories about outrageous prices and medical bills can help build awareness of America’s very expensive health care system, the next batch must take a harder look at the remedies and politics that are preventing significant change. I decided to take a look myself to see what information and protections are available.

Checking state laws won’t give most people a lot of help when it comes to surprise billing. Last year a Commonwealth Fund study found many states “typically rely on market forces to minimize balance billing.” Among the 21 states with some sort of law, only six (New York, California, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland and Florida) had statutes that could be considered comprehensive. That means in those states protections apply to people in HMOs and PPOs. They extend protections to patients who use emergency rooms as well as in-network hospital settings, and patients are not bound to pay the extra charges.

The ongoing dispute between doctors and insurers is sure to be central to any legislative action next year. Insurance companies want to keep networks narrow and, according to Hans Leida, a consulting actuary at Milliman, “Network providers are one of the few levers available to them to manage the risk.”

In other states there are significant gaps in protection from surprise bills. Consumers may find the protections apply only if their case involves emergency room treatment not if their care is delivered to them as an inpatient. Their laws may apply only to disputes involving HMO coverage. If they’re in a PPO, they’re out of luck. And if they are in self-insured plans, which are common among large employers, state laws don’t apply.

Last week a bipartisan group of six senators introduced a discussion draft of legislation that would begin to regulate surprise bills. It appears the proposal would bring patients some relief. They would have to pay only for inpatient cost-sharing.

The ongoing dispute between doctors and insurers is sure to be central to any legislative action next year. Insurance companies want to keep networks narrow and, according to Hans Leida, a consulting actuary at Milliman, “Network providers are one of the few levers available to them to manage the risk.” For example, if the insurer doesn’t want a lot of claims for mental health, it may include few psychiatrists in their network. “They are definitely getting pickier,” Leida told me. “Carriers are moving to HMOs with more limited networks.”

Michele Kimball is the president and CEO of Physicians for Fair Coverage, a group of doctors lobbying for state legislation. She told me doctors are “willing to accept a ban on balance billing. They just want to be fairly and adequately reimbursed.”

Chuck Bell, program director for Consumers Union, says the discussion draft of the bill that was released last week “does nothing to fix the underlying problem of faulty health plan networks that lead to surprise bills and disruptions in care to begin with. Congress has to find a solution that will be accepted by both providers and insurance companies at the national level where their lobbying power is the strongest. That’s extremely tricky from a political point of view.”

After I did my own research, I learned what Bell meant. I visited the website of the National Conference of State Legislatures to see what help it might be to viewers of the CBS Morning show. A number of states require the posting of say, 50 or 75 or 100 common procedures, but if what you need is not among them, then you’re out of luck. What exactly has to be posted is sometimes vague. For example, one state says “the normal cost of services prior to treatment” is to be posted, another says the average reimbursement rate should be listed. But what is “normal” and how many people actually pay the average? Most states don’t require hospitals to give patients an itemized bill if they ask for one. An itemized bill gives you a good idea of how much the care you receive actually costs and helps sensitize you to the overall problem. It also helps you figure out if the care you received was within your insurer’s network.

The requirements in the states listed on the National Conference of State Legislatures’ website seemed weak to me, and read like compromises between hospital lobbyists and a few consumer-minded legislators. I discussed all this with Bordewyk. Yes, he said, a few years ago there was a legislative effort to give consumers some basic overall price information in South Dakota. But the hospital lobby pushed back and the result was a compromise giving some basic information about median charges and demographics. “This is how the health care providers want it. They aren’t trying to make it more consumer-friendly.”

And that’s the danger Bell is warning about with any potential federal legislation next year regulating surprise billing.

That aside, a robust debate next year that leads to legislation, with the press following its twists and turns through the legislative process, might just result in help for victims of surprise bills.

Veteran health care journalist Trudy Lieberman is a contributing editor at the Center for Health Journalism Digital and a regular contributor to the Remaking Health Care blog.

[Photo by Lauren via Flickr.]